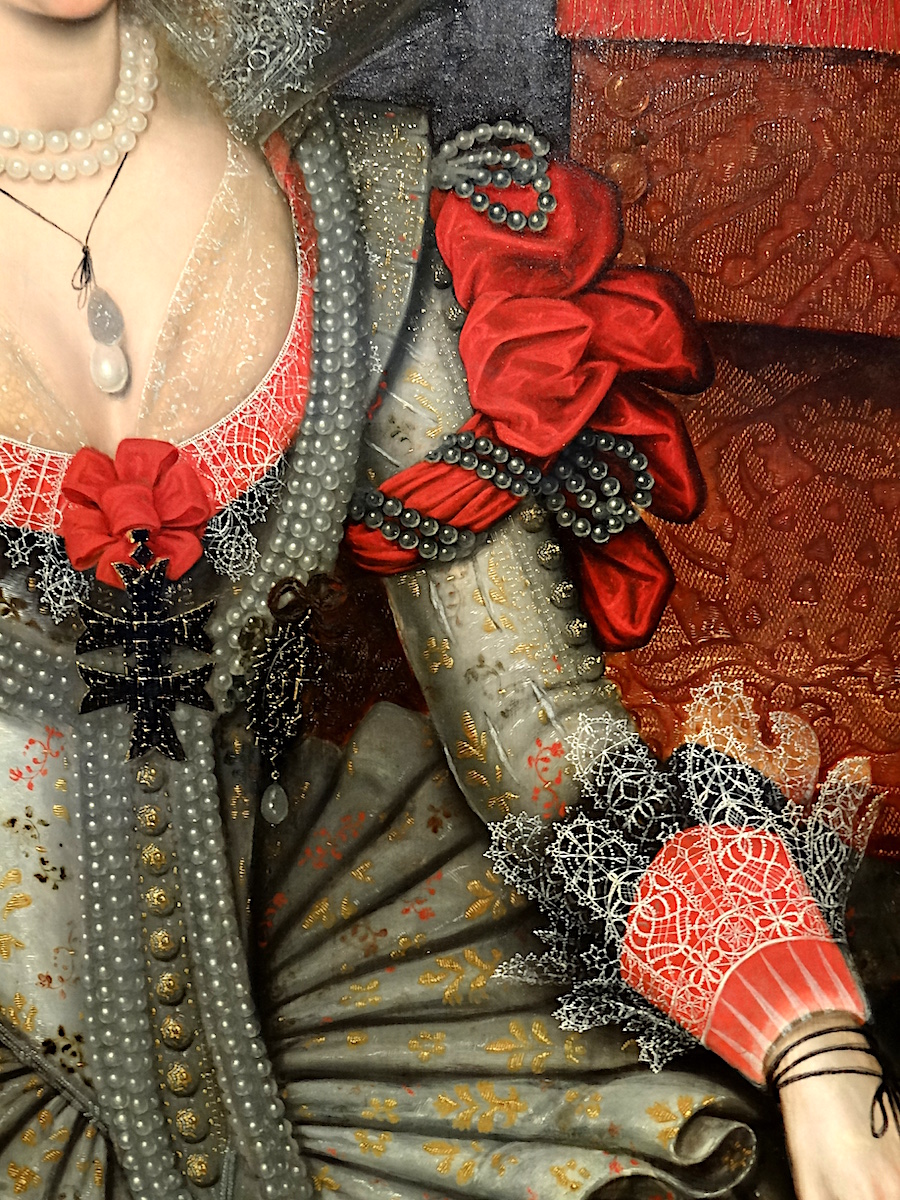

Rex Harris / Flickr

There is bling, and then there is ye olde embroidery. Seventeenth century needlework was to the rich what, say, Alexander McQueen was for contemporary fashion. An injection of fairytale whimsy into every day life; needleworking unicorns on your bustle, and roses on your collar. Threading gold into your slippers, and gems into the cuff of a glove. It was a style at once over-the-top, yet down to earth in its ties to folklore and cultural patrimony. These Jacobeans didn’t just dress well. They dressed themselves into Narnia…

@ Hungarian National Museum. Kotomi_ / Flickr

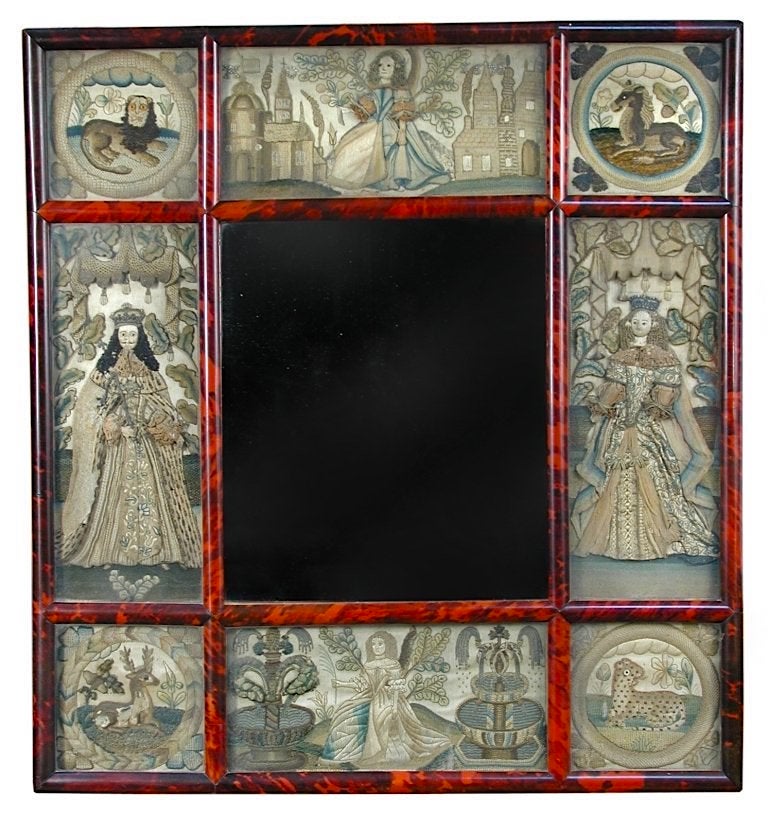

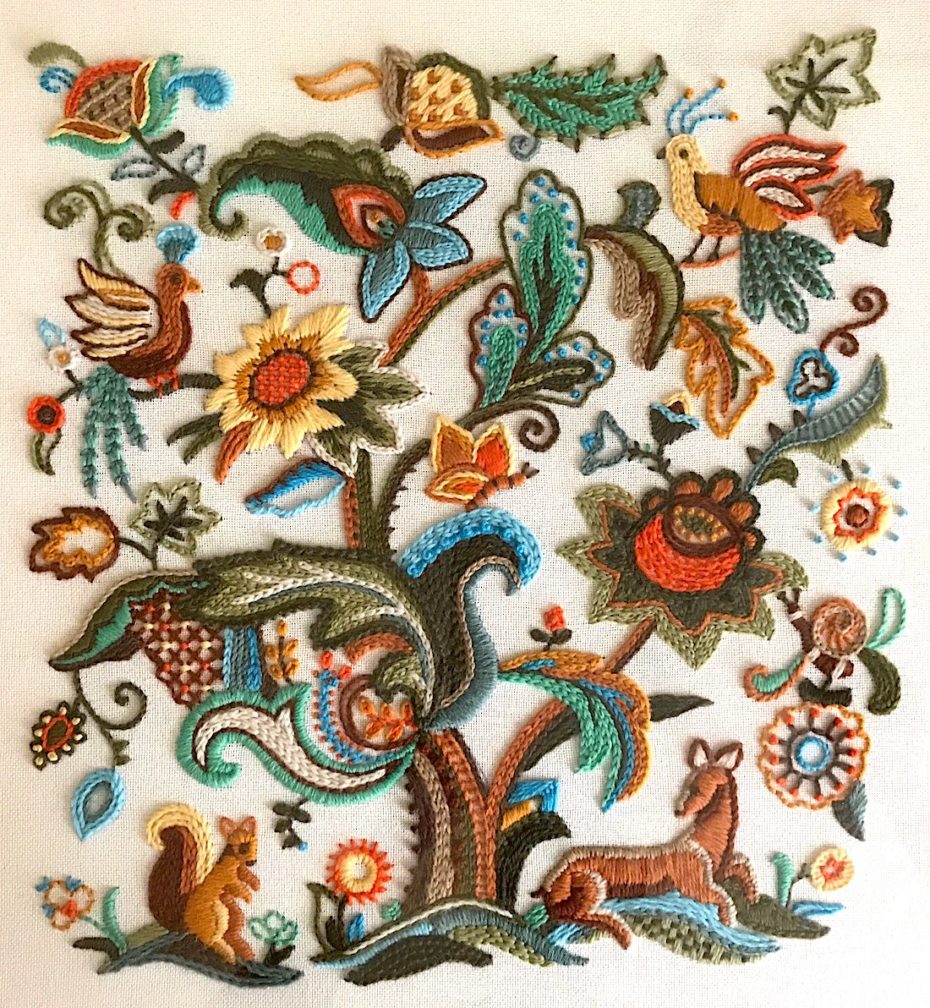

The “Jacobean” style of needlework isn’t so much a kind of sewing technique as it is a vibe (and a reference to the Latin translation of King James I). It refers to a kind of mood board wherein highly stylised mythical creatures, plants, and maidens reign supreme. The Tree of Life was a popular motif. So too were cherubs, chivalrous scenes, or imagery inspired by England’s most recent trade partner: India.

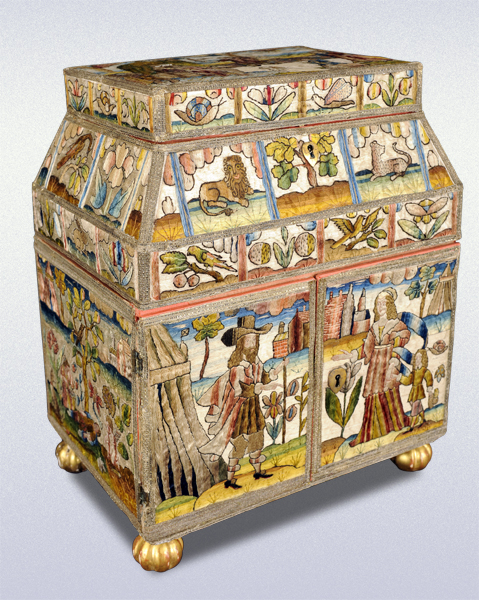

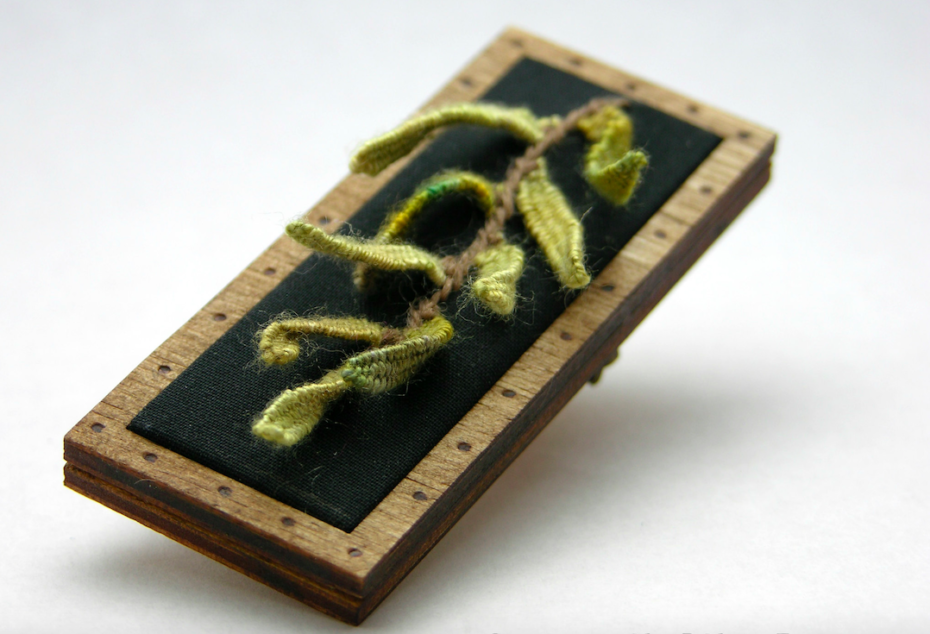

“Crewel” and “stump” work sewing techniques created complex layers of metal, silk and wool threads, adding a richness and dimension to the designs that made them, quite literally, rise from the surface. This included not just clothing and accessories, but precious boxes called “caskets” and hand-sewn “paintings,” frames, and wall panels.

Given the fragility of 400-yr-old fabric, these smaller items are some of the best remnants we have of the art form, which was time consuming, to say the least. One piece required an entire professional sewing team with highly specialised tasks; Roger might be assigned background painting, while Simon worked on gold embroidery, and so on. But no matter. The work was often done anonymously, and always done by men.

“In trying to think of a contemporary form that is comparably labor intensive, animation came to mind,” explained specialist Susan Brown in a 2012 interview with Cooper Hewitt. In a way, it could be seen as an early form of 3-D printing. There were “some earlier attempts at portraying movement,” she says, “[but they] are more related to sequential narrative or comics. The Egyptian Book of the Dead for example.” These pieces walked right off their tapestry, so to speak…

So revered was the craft, that societies like “Keepers and Wardens and Society of the Art and Mistery of the Broderers of the City of London” were invented. And if the said guild or client should be displeased with the final product? It was cut up and burnt.

Today, we’re delighted to know that the craft of such fanciful needlework lives on in far less didactic means. Just ask our favourite, needlepointing Parisian witch, or England’s Royal School of Needlework (RSN), est. 1872:

As for some throwback Jacobean pieces, the UK’s Royal School of Needlework is turning out some lovely work:

The Victoria & Albert Museum, which has an impressive collection of Jacobean textiles in its collection, frequently hosts embroidery workshops.

Our incoming 2020 resolution? Embroider more, stress less. Check out the RNS’ online classes and lovely e-boutique for more.