For so many US veterans, the real journey home begins in the head – that long, winding road to psychological stability after the traumas of service. Even today, it’s a topic not easily broached given the stigmas surrounding mental health. It wasn’t until 1980, and under much controversy, that the American Psychiatric Association added the term “PTSD” to its diagnostic manual and classification scheme. And yet, unbeknownst to many of us, one Oscar-winning director, John Huston, made a revolutionary film for the US government to destroy that stigma way back in 1946. Then in service for the army, the legendary director was asked to make an educational public film about soldiers with PTSD. Not only was it a totally unscripted documentary (then unheard of), but it was paired with Huston’s film noir-worthy cinematography to produce a raw and powerful window into the soldiers’ fragility. But the US Government decided the public wasn’t quite ready for the reality of PTSD and decided to keep it confidential for 30 years – lest the “All American Warrior” myth should take a blow. Frankly, it’s the most inspirational film we’ve seen in ages. Ladies and gents, may we present Let There Be Light…

Admittedly, we sat down expecting a mildly better version of those hokey 1950s instructional videos – but boy, were we wrong. From the moment Let there be Light begins, you’re hooked in by its principle ‘characters’. Huston’s crew shot roughly 70 hours of film, and whittled it down to under an hour of absolutely fascinating viewing.

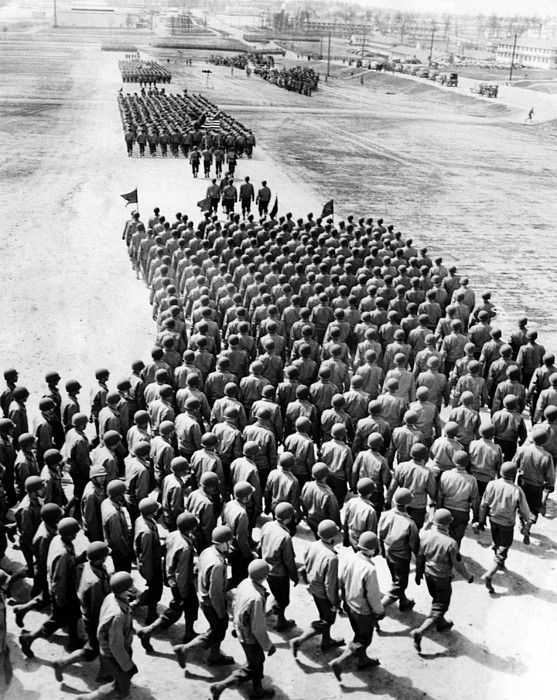

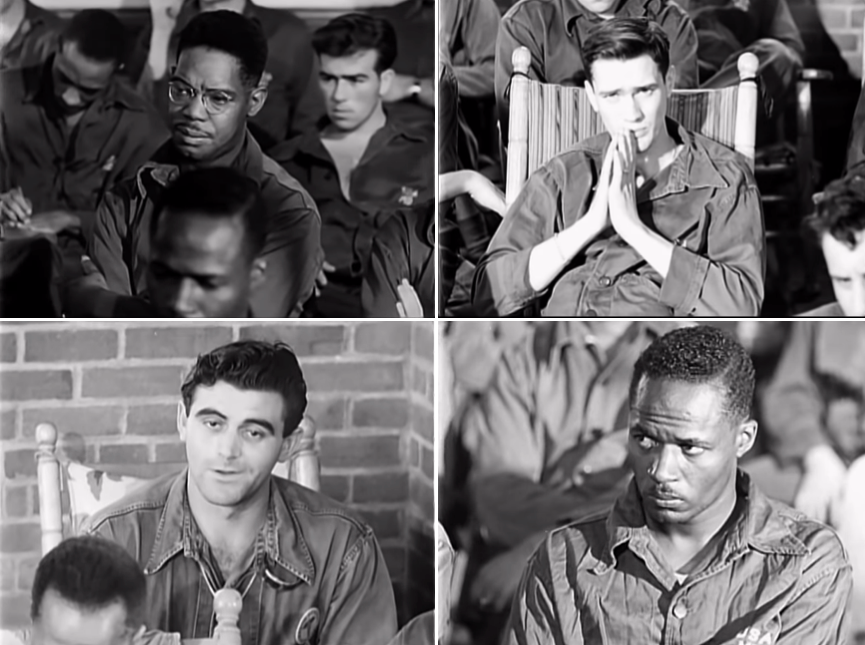

“The guns are quiet now. The papers of peace have been signed,” says narrator – incidentally, Huston’s father – while the camera scales a ship’s black portholes, filled with the faces of returning soldiers. The camera continues to pan, the men become smaller, and discussion begins of their “invisible” battle scars. “In faraway places men dreamed of this moment,” Huston Sr. says, while a silhouette descends the ship, “but for some men the moment is very different from the dream.”

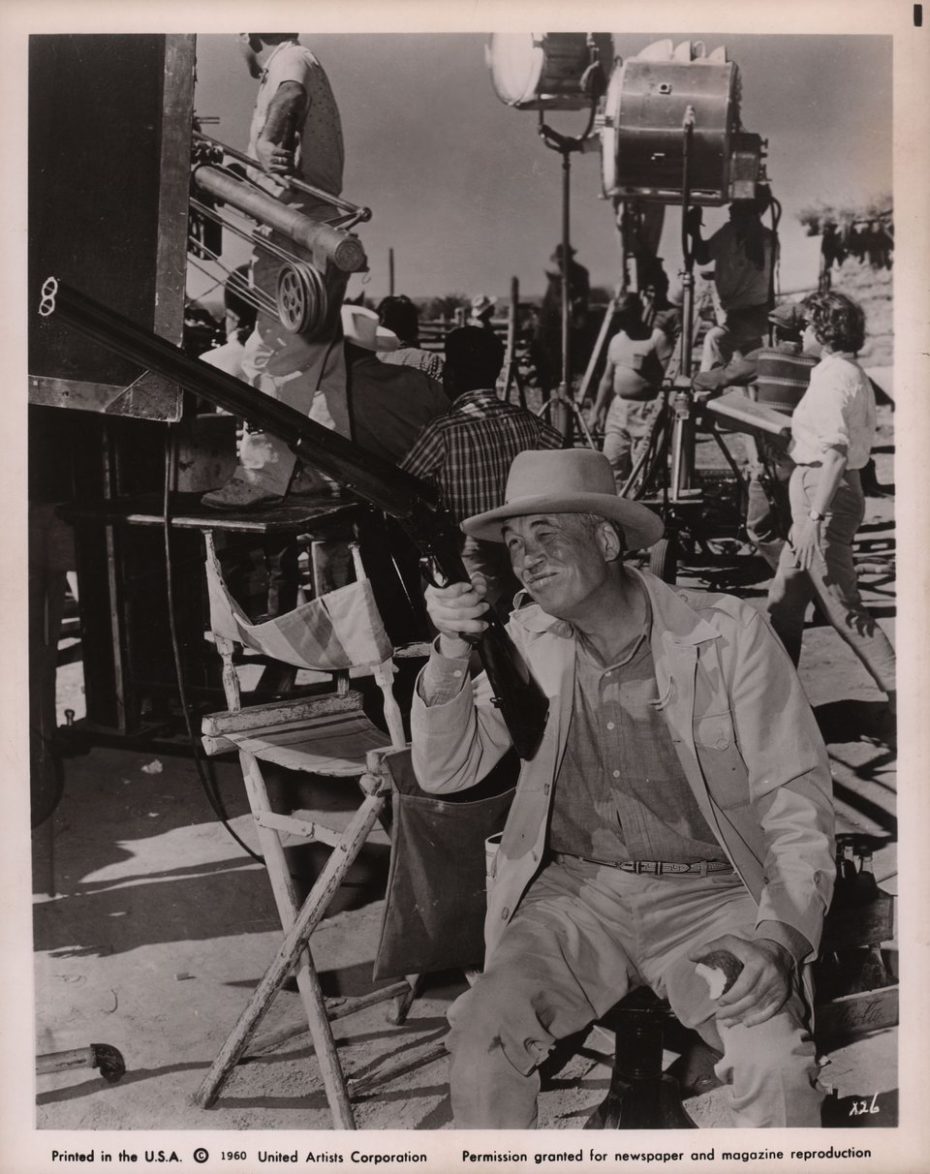

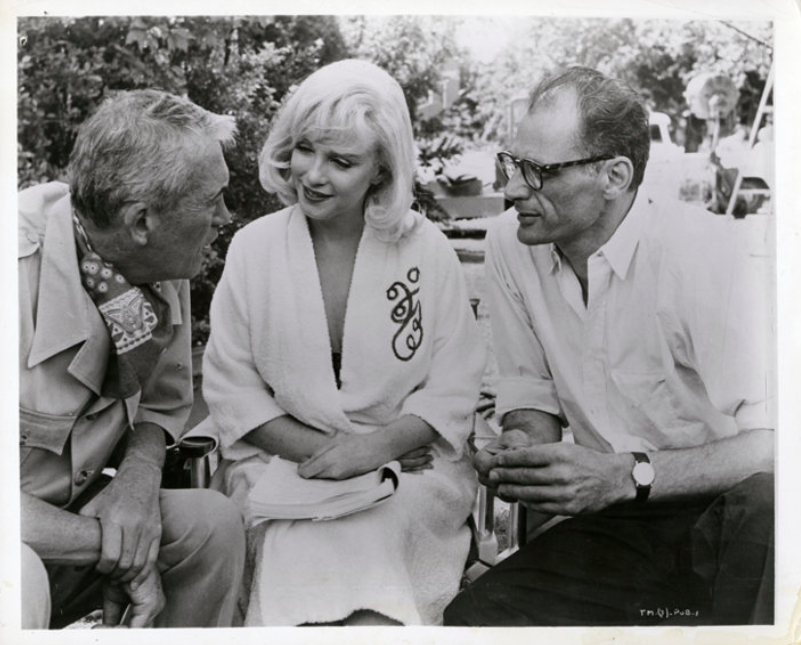

Quick reminder, folks, that American media culture around this time usually hit three notes: harmless comedy (The Three Stooges), über hetero-masculine (Lone Ranger), and whatever fit in-between. You may also know Huston – who has been described as “cinema’s Ernest Hemingway” – as the director of The Maltese Falcon (1941), The African Queen (1951) with Humphrey Bogart and Katherine Hepburn or The Misfits (1961) with Marilyn Monroe. If it was epic, he probably directed it.

He was also the father of one of our favourite actors, Anjelica Huston:

Maltese Falcon had really tested the limits of Hollywood’s new “Hays Code,” which ushered in an era of suffocating, “moral” content codes for filmmakers. Then, just one year later, Huston was called to serve in WWII. The government, recognising his talent, asked him instead to create three Army propaganda films: 1943’s Report from the Aleutians (a film about prepping for combat), 1945’s The Battle of San Pietro (also initially delayed due to its unflinching content), and Let There Be Light, whose title referenced Genesis 1:3 of the King James Version of the Bible – code for Huston’s plan to reveal the truths from the “void” and “darkness”.

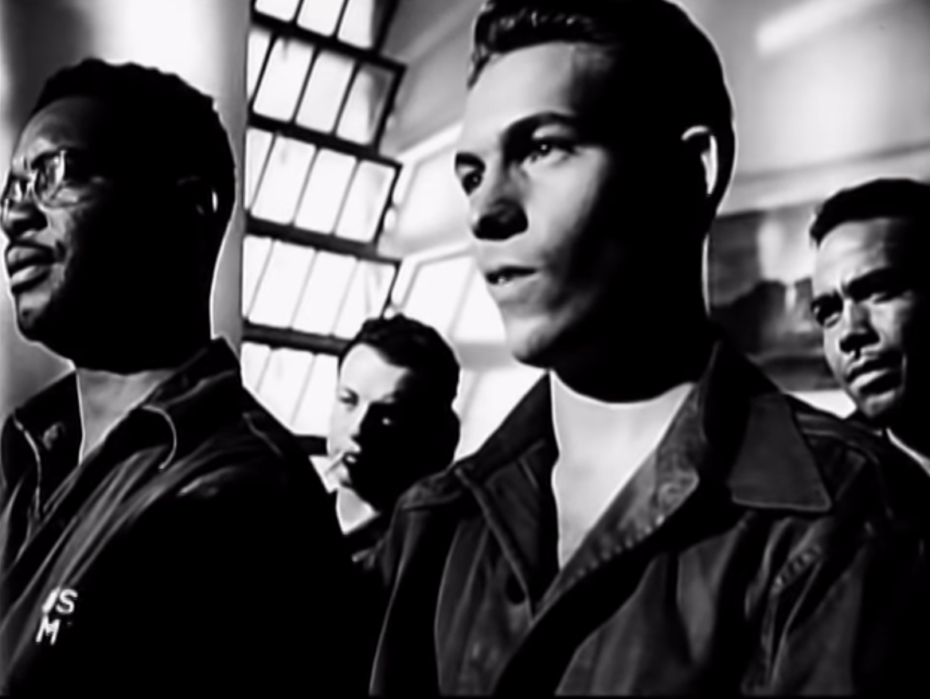

Huston wasn’t kidding. Emotions weren’t airbrushed during scenes of medical hypnosis and psychotherapy. There were no actors, no run-throughs or planted lines. These men smile, cry, and tremble. They also do so together, regardless of skin colour, as the Army was desegregated. As such, the film is truly an unparalleled historical treasure…

“I visited a number of Army hospitals during the research phase,” Huston later said, “and finally settled on Mason General Hospital on Long Island as the best place to make the picture. It was the biggest in the East, and the officers and doctors there were the most sympathetic and willing.”

75 new patients were admitted every week, and expected to complete an 8-10 week program that would, as Huston put it, “restore these men physically, mentally and emotionally.” As viewers, we follow a handful of the men from the day of their arrival, to the minute their bus pulls out of the centre.

For an unscripted film, the story’s arch is incredibly tight – and played out with sublime contrast not only in character development, but film style (ex. the film noir-y shadows, dramatic angles).

At the climax of World War II in Europe just two years earlier, the mighty General Patton had visited an evacuation hospital away from the front lines and found two soldiers there without apparent physical injuries. In an incident that would later be published in the press as the “George S. Patton slapping incidents”, the General of the United States Army struck and berated the soldiers, scoffing at their invisible effects of PTSD and accusing them of cowardice.

When the incidents were leaked to the press, Patton was ordered to apologize to the men and sidelined from combat command for almost a year, but public opinion was largely favourable to Patton. It has since been speculated that Patton himself suffered from PTSD, which may have caused patterns of brashness and impulsiveness in his behaviour. At the time, the complexities of PTSD as we understand them today were referred to as “battle fatigue” or “shell shock”.

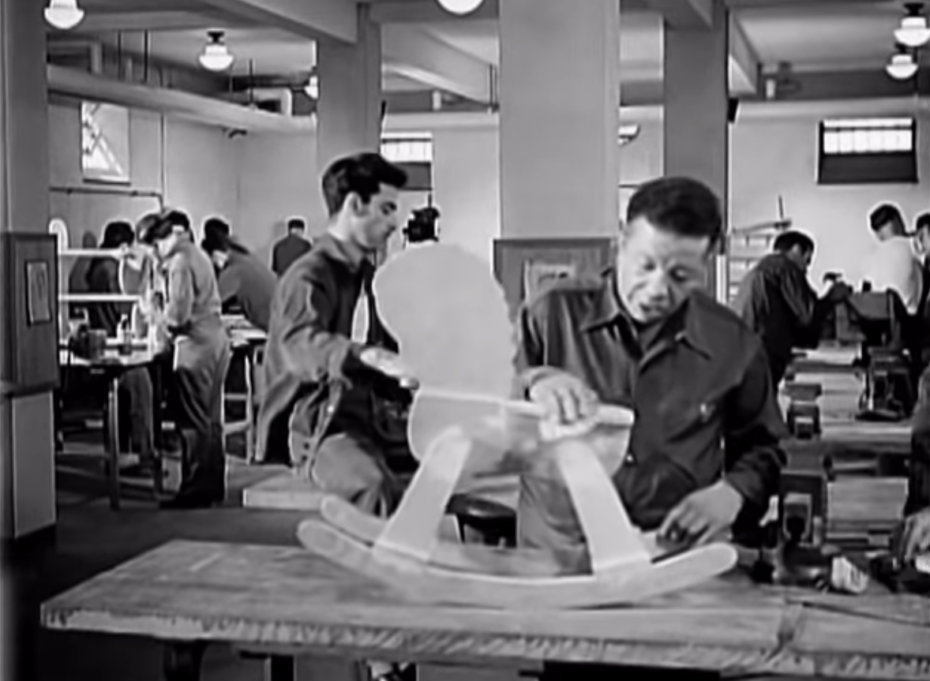

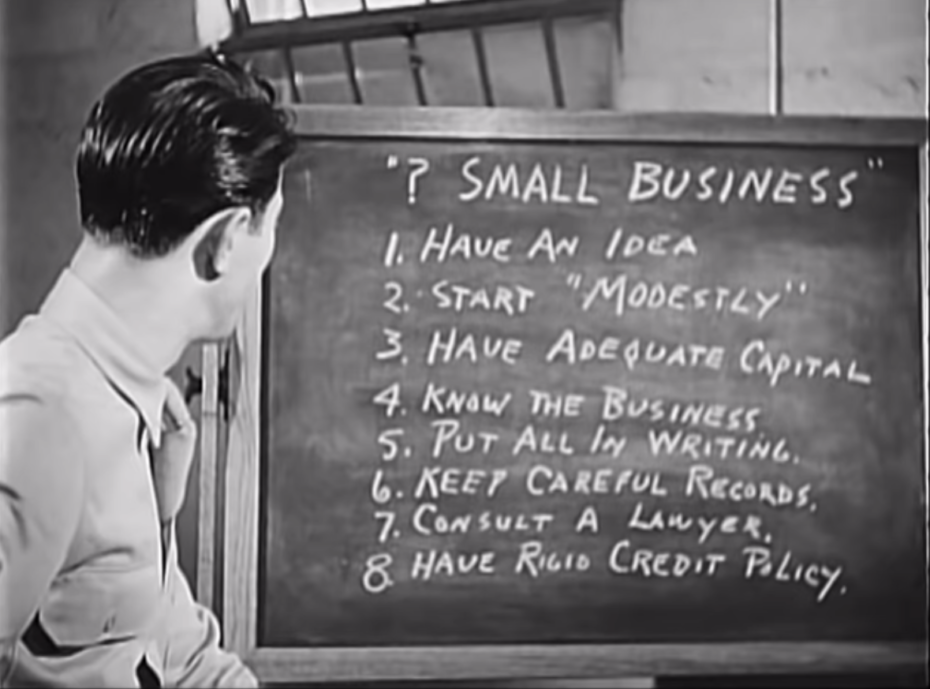

“The original idea,” says Huston, “was that the film be shown to those who would be able to give employment in industry, to reassure them that [these men] were not insane, but trustworthy as anyone.” As such, we also get the treat of seeing what the soldiers create in their occupational and art therapy.

There are many moments where we see what’s at the root of the soldiers’ PTSD – but oftentimes it begins with their war trauma, and digs deeper, into an episode of their childhood, or a pre-existing condition. One man sites his “rough” dad. Another man says he couldn’t speak until he was seven years-old.

One of the most moving scenes occurs between a black soldier and a psychoanalyst. “How’ve you been getting on?” the doctor asks. “Fairly well sir,” says the soldier. The doctor asks if he’s having “crying spells.” The soldier responds, “Yes sir. I believe in your profession it’s called nostalgia.” It’s a powerful moment, and one made all the more poignant when he pauses, and begins again, “It was induced when, before the war, I received a picture of my sweetheart.” Just as he starts crying, and apologising for crying, the doctor stops him – “A display of emotion,” he says, “is sometimes very helpful. It gets it off your chest.”

This wasn’t a film feeding into the Army’s toxic “tough guy” trope. It showed another side of strength.

All the film’s talk about “submerged regions of the mind” was also pretty far out for 1946 (decades before Americans would turn on, tune in, and drop out with Timothy Leary and the hippies).

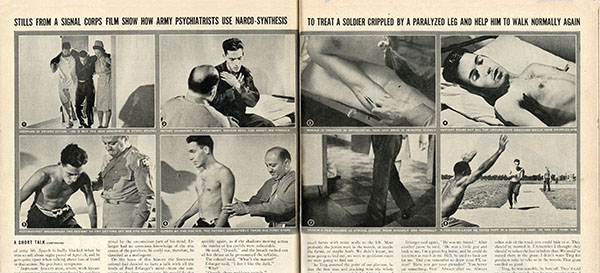

When the Army saw the finished product, higher powers pulled the plug on the movie, citing concerns for the soldiers’ privacy. In contradiction to this, the Army approved several film stills from Huston’s footage (which clearly show the soldiers’ faces) to be published in a 1945 article for Life magazine on the treatment of “battle-fatigue” for wounded soldiers. Why was a powerful film tackling the complexities of PTSD denied a release? The decision would help push back the awareness and progress for PTSD treatment by another four decades.

Having kept a copy of the film, Huston allegedly went ahead and secretly screened it at the Museum of Modern Art. It was only in 1981 that the Oscar-winner’s film was finally screened at the Cannes Festival with the help of a new, more sympathetic Secretary of the Army. The New York Times called it, “an amazingly elegant movie,” citing that even though “today’s audiences [have] grown up seeing riots, wars and assassinations live-and-in-color on their home television screens,” the film hits home – it’s starts with the head, and ends at the heart.

Watch the full movie below:

If you or a loved one is a veteran suffering from PTSD, the Veteran Combat Call Center is a 24/7 hotline where you can talk with another combat veteran: 1-877-WAR-VETS (1-800-927-8387).