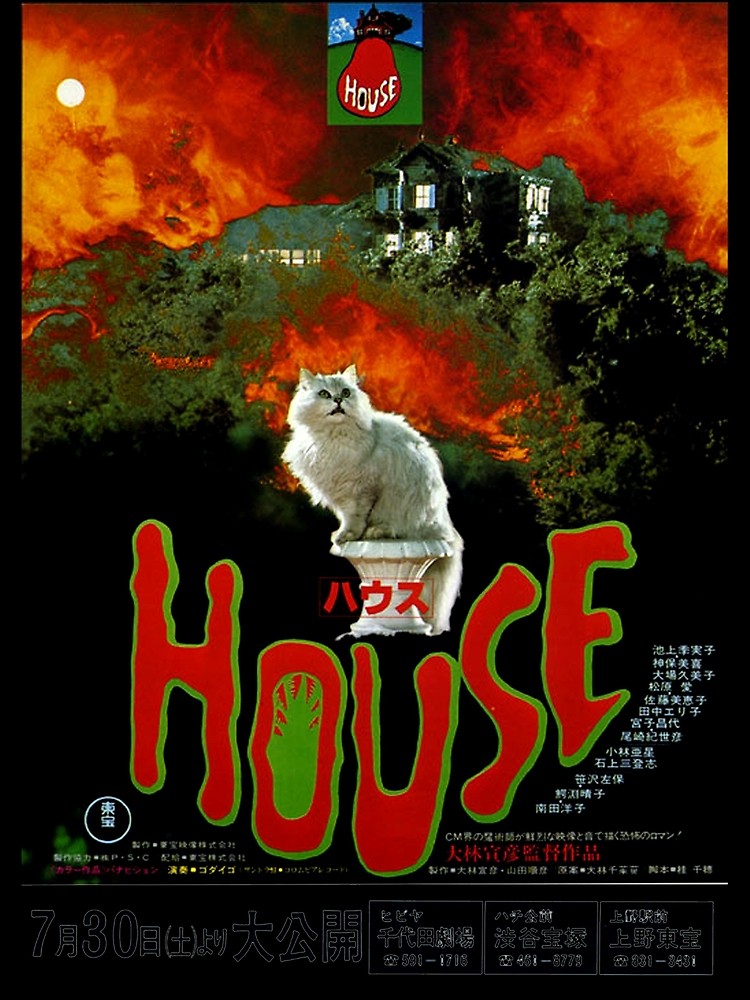

If home is where the heart is, House (1977) is where the mind unravels. The experimental film by director Nobuhiko Obayashi is a beautiful, Surrealist venture into the horror genre that’s slowly but surely getting its due credit in the Western world. Where to even begin with Mr. Obayasi? His finger-eating piano? Ghostly watermelons? He’s David Lynch, dipped in acid. He’s summed up in one expression in his native Japan, “Obayashi World” – a kind of shorthand for amalgamating madness, humour and psychedelia to bridge conversations about post-war Japan, adolescence, and autonomy. Also, killer cats. Let’s just get to the trailer already:

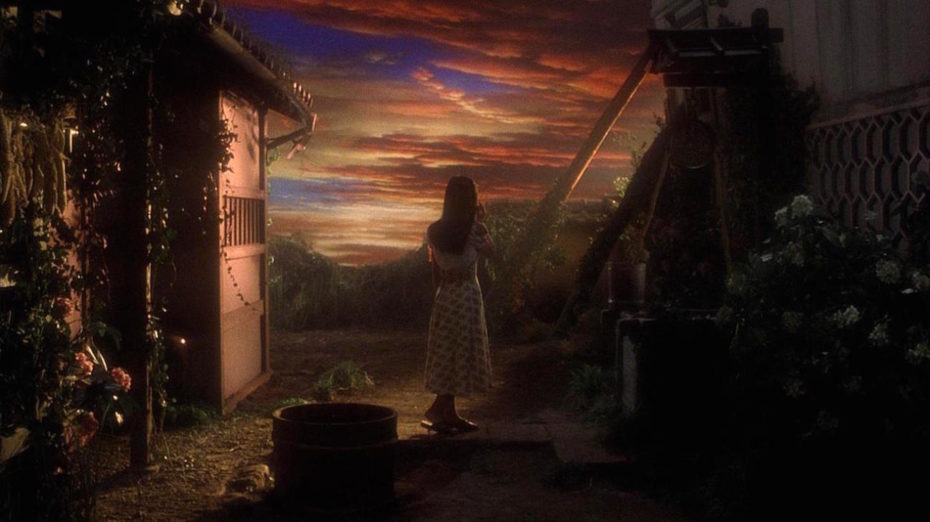

We should mention: House isn’t horrifying. It’s actually really beautiful, like watching a cut & pasted collage of a lucid dream take shape. We follow a group of seven girls into a haunted house as it consumes them, one by one…

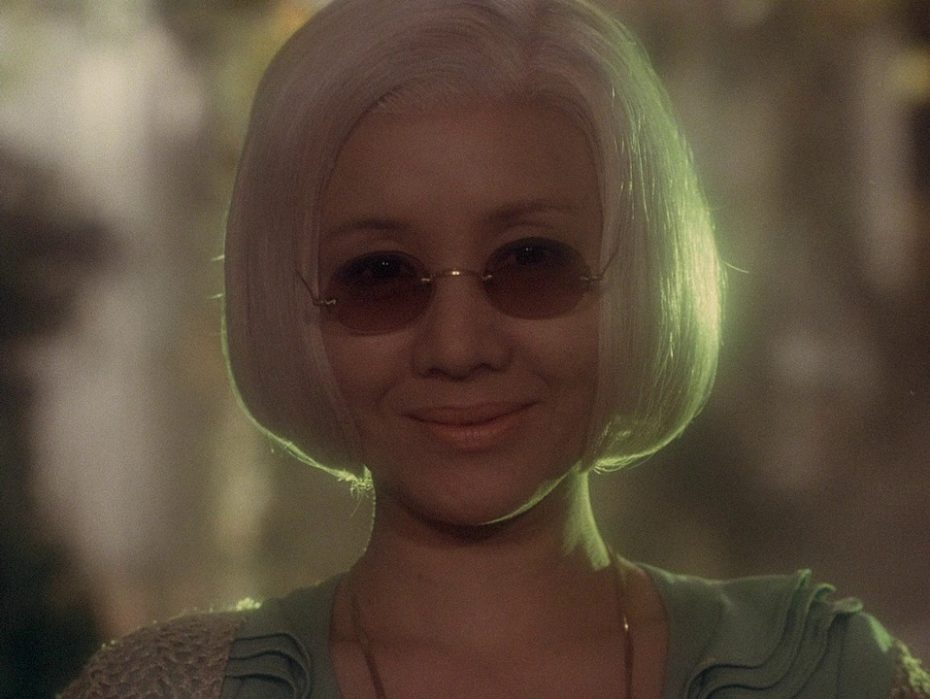

It all starts when a girl named Gorgeous, distraught by her widowed father’s decision to remarry, writes to her aunt for help – couldn’t she just go to Aunty’s house, and get away from it all next summer? The aunt gives her the green light, and the ok to bring friends whose names are also a nod their personalities and imminent deaths: Prof (the smart one), Fantasy (the daydreamer), and Melody (the musical one); Kung Fu (the athlete), Sweet (the gentle one), and Mac (the glutton). They’re all dressed to kill, or rather be killed, in the dreamiest of 1970s ensembles.

The film gets increasingly absurd and kitsch, thanks largely to its cut & paste visuals that would’ve been outdated by 1940s standards. Superimposed, floating limbs and groovy flowers pop out of nowhere, while eerie cartoon heads and juvenile, collaged vortexes spiral out of control. It’s a delight, and Obayashi paying homage to a specific kind of crazy: the teenage brain.

Obayashi says he took a lot of inspiration from his own 11-year-old daughter when making the film, and often cites the importance of childlike curiosity in his creative process. “[Adults] only think about things they understand,” he said, “everything stays on that boring human level [while] children can come up with things that can’t be explained.” Y’know, like a psychotic cat – which you may or may not recognise from various viral GIFs:

There’s also something pretty damn gratifying about seeing these ladies go totally crazy on their poltergeist foes:

House‘s pop art style also finds roots in Obayashi’s background in commercial advertising, not unlike our own Andy Warhol (almost all the women in the film, in fact, were friends of Obayashi from his advertising days). When he was in his twenties, Obayashi started getting into experimental films and the underground art scene, rubbing shoulders with Yoko Ono. It wasn’t until he finally approached a studio with the idea to create a Japanese version of Jaws (1975) that he was given his first chance into big (or, bigger-ish) budget filmmaking. He jumped ship on the idea of a Jaws remake, dreaming up Hausu (House) instead…

It made little to no impression on its release. Over the years, it gained a kind of cult film status, and is still gaining traction with Western audiences; it received its first domestic theatrical run in the United States in 2010. It’s also one of so many powerful films he’s made in a career spanning 60-years. There’s Hanagatami (2017) a beautiful film about post-war Japan that was 40 years in the making, and what he identifies as his masterpiece; there’s 1982’s Tenkōsei (or, Exchange Students), about a boy and girl who magically switch bodies.

But none of them are given the same acid tab as House, whose layers of goofiness hide real depth. Obayashi was born in Hiroshima in 1938, and he’s been devoted to telling its story – the good, the bad and truly tragic – in his films.

“It’s our responsibility to communicate the reality of the war to young people who never experienced it,” he told Japan Times in 2019, when discussing his latest film Labyrinth of Cinema (2019), which follows three men who time-travel to Hiroshima a few days before the atomic bombing. House, in its own way, deals with the loss of war at its most raw and infantile. It’s a homecoming, albeit to a house of ghosts. We see a new generation open the metaphorical doors to a future of surreal logic, in a way that continues the Surrealist and Dadaist mantra of post-war creativity: get grotesque.

There are artists who move us so much, their names become an adjective for the worlds they’ve created. We indulge in Proustian treats, and drift into Kafkaesque nightmares. In matters of cinema, “Lynchian” has always been one of highest compliments for a weird new movie: that of a unique, strangely sinister – yet familiar – universe. Funnily enough, the same year David Lynch unleashed Eraserhead (1977), Obayashi released House. We like to think they were born in the same, cosmic petri dish – and that Obayashi might find some new fans amongst our own little community.

Until then, queue it up for your next movie night with friends. Especially if you happen to have a cat. Find it streaming on Amazon.