If there’s one thing Messy Nessy’s editorial team has in common, it’s that we’ve never quite been able to keep a normal 9-to-5. Which is why we love to learn about the ins-and-outs of the oddest jobs out there; the gigs behind the everyday things we may take for granted. Like your drive to the supermarket. There’s a whole fascinating – and sometimes, a little unsettling– story behind what makes your Volvo safe. Turns out, the road to safer driving opens up a dialogue on a fascinating, weird industry that’s riddled with ethical speed bumps and safety saviours. So strap yourself in as we retrace the unsung story of its curious hero: the human dummy.

First a bit of background. Commercial automobile production hit its stride at the end of the 19th century, and by the 1930s cars were no longer a luxury. Unfortunately, that democratisation didn’t necessarily make for safer vehicles. Seatbelts weren’t even mandatory until 1968. Cars were great, but they were like coffins on wheels. And people just kind of accepted that.

One team begged to differ. In 1939, researchers at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan started testing collision impacts on cadaver skulls. From there, testing only expanded (they also threw a body down an elevator shaft). Testing took place primarily within universities with amazing medical resources, instead of within automotive companies themselves. How they acquired these cadavers remains vague, bringing to mind those 19th century body snatchers that robbed graves of their cadavers (all in the name of science).

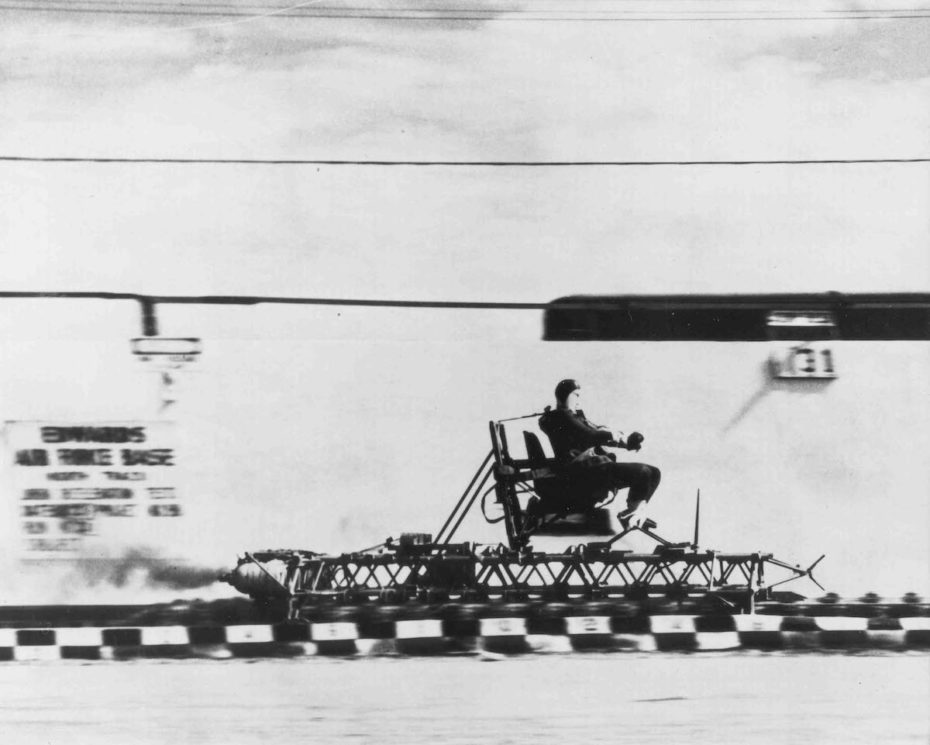

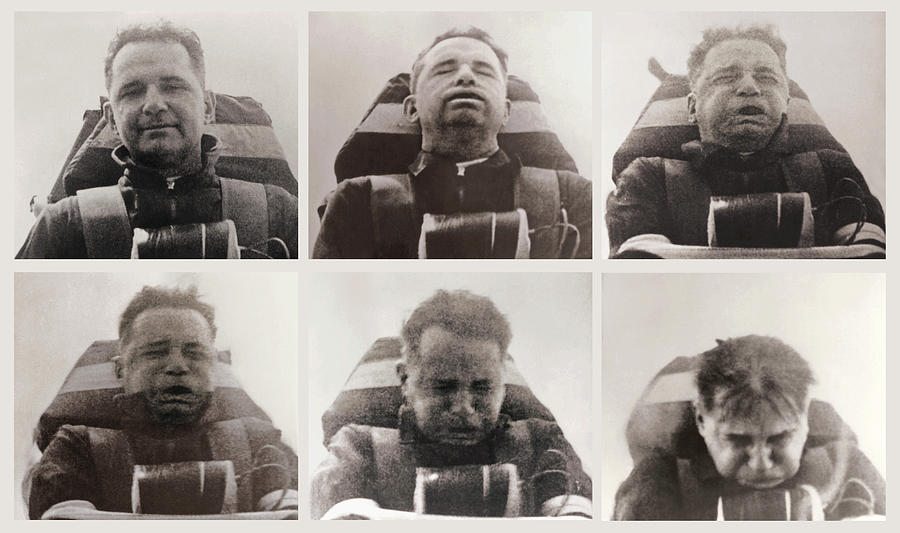

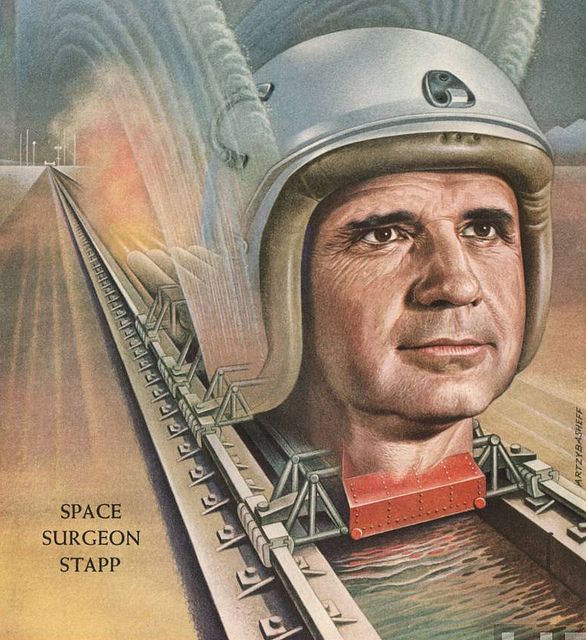

There were those who donated their bodies to science, but even at the height of cadaver testing in the 1960s, the average was about one cadaver per month. So researchers literally took matters into their own hands, becoming human “dummies” of sorts. Consider USAF Colonel John Stapp, who happily strapped himself into NASA’s “Rocket Sled” in the 1950s. The apparatus moved more than 1,000 km/h in just over one second. Wayne State professor Lawrence Patrick also volunteered himself – more than 400 times, actually.

Human dummy testing continued to flourish into the latter half of the 20th century, and notably in a 1991 article for The New York Times. In the piece director of research and development for the Government’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, George Parker, states that the use of animals had been phased out in the 1970s (but research shows that bears and pigs were still used into the 1980s). In fact, General Motors didn’t stop live animal testing until 1993, and although it may be rarer today, cadaver testing is still a thing.

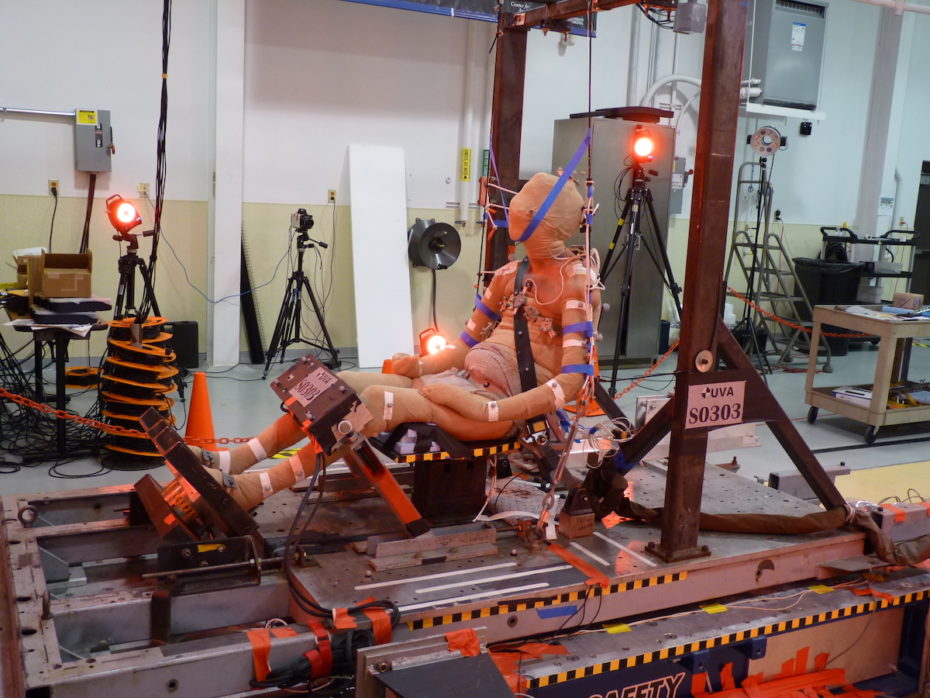

While dummies have sensors throughout, which allow crash test engineers to see exactly what forces the dummy was exposed to and how strong those forces were, they can’t tell researchers everything that happens to the human body in a crash. Cadaver testing has dwindled, but it still exists. It’s just a kind of awkward topic for automakers and research institutions to broach in the media. In 2007, a US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health document revealed that the child-sized “FE model” dummy actually incorporated the neck of a real child. So what was it, then? A cadaver? A dummy? Were they playing Frankenstein in those testing labs?

But the tests do make a difference. According to the Association for Safe International Road Travel (ASIRT), an average of 3,287 people die in a car crash daily. Design changes made in light of cadaver testing, however, started saving around 8,500 lives annually by the late 1980s. Which is where our human dummies, once again, come in to things…

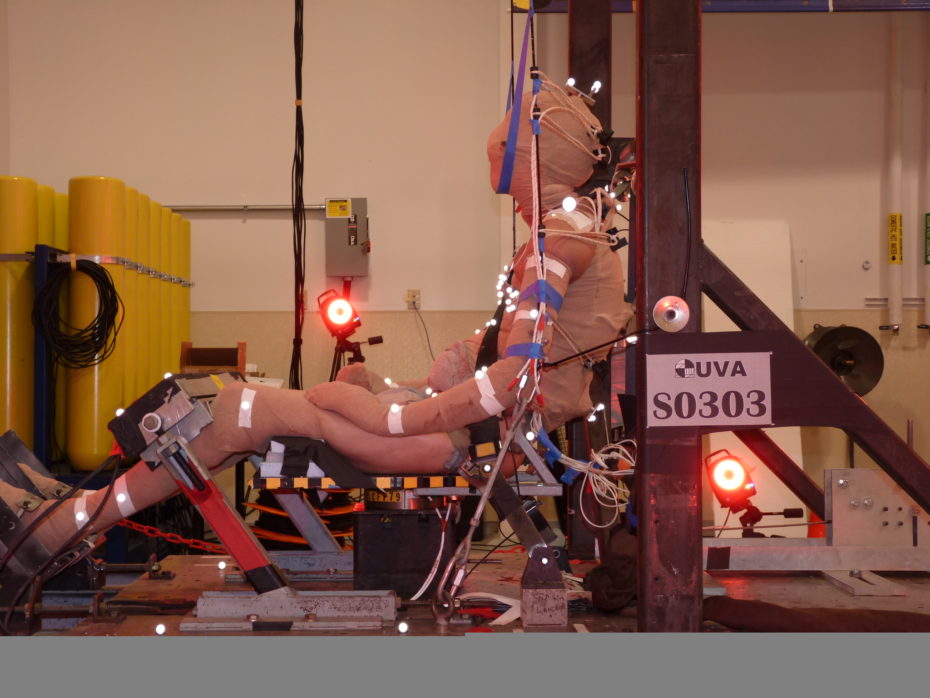

There is constant need for new, living surrogates even as technologies advance. Rusty Haight is a proud human crash test dummy, who through out an ask-me-anything post on Reddit in 2013. “I have driven in more than 900 crash tests to date,” he wrote, “and hold the Guinness World Record for ‘Most Human Subject Crash Tests.’ I teach crash investigation and analysis worldwide and have been investigating and analysing crashes for more than 30 years. For the last 20 of those 30 years, I have been the driver in full scale crash tests.” Here he is in action:

Rusty became a dummy, as it were, when he was a police officer in San Diego. “[I] worked in the Accident Investigation Bureau and was offered a job in the private sector as an accident investigator,” he says, “I took that job which lead to a teaching job – teaching accident investigation – which lead to research. Driving in crash tests is part of the research. It’s a lab.”

Rusty is very passionate about educating the public on what goes on behind automakers’ doors, and had some great tips when it came to staying safe – and simply answering the public’s burning questions. Like, what’s his favourite car? A Land Rover Discovery. His serious injuries? None, really. Does he have a hard time looking or getting accepted for Death Insurance? “Actually,” he says, “[I] had a more difficult time getting insurance because I am a SCUBA diver.”

And what, of course, is the best way to stay safe? “Always wear your seat belt and wear it properly,” he wrote, “low on your hips and properly across your chest. Not behind your back or under your arm. Take advantage of the safety features they build into your car: they’re there for a reason! Don’t sit ‘out of position.’ Don’t put your feet up on the dash over the passenger airbag or out the window . Don’t sit on your feet so the seatbelt is out of position.” In other words, buckle up before you enjoy the ride.

You can actually attend crash tests and research days. Learn more on the official site for the Institute of Traffic Accident Investigators.