It’s the best Agatha Christie novel that never was: the story of the disappearance of Manhattan perfume heiress, Dorothy Arnold. She was a woman about town and the belle of too many Uptown balls to count, but to this day, no one could ever figure out whether Dorothy was murdered, kidnapped, or stepped through some kind of inter-dimensional portal. More than a century on, however, the most poignant part of Dorothy’s story is perhaps not what happened to her, but how it was investigated: her own family decided not to report her missing for fear it would tarnish their reputation, making Dorothy’s tale a reminder of the disturbing power and leverage that such classism had on the public, the press, and even the sympathetic police force.

But first, a little portrait of a not-so-happy family. Dorothy came from serious money with direct lines back to Mayflower passengers. She was well educated, and graduated with a major in literature from Bryn Mawr College. Her highest aspirations were to become a writer, although she wasn’t having any luck getting published. Her parents, Francis and Mary, always tried to steer her away from the ‘bohemian’ profession. Writing was not a woman’s game, and certainly not in their upper-crust family. When she begged her father for an apartment in Greenwich Village, he rolled his eyes, “A good writer can write anywhere,” he told her. So back home it was, to 108 East 79th Street where there was little room to rock the boat. Or so one would think…

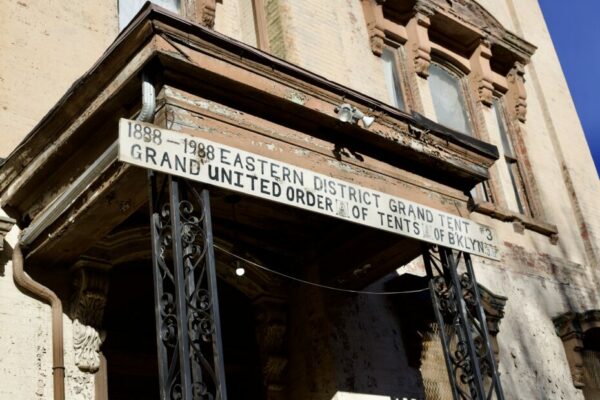

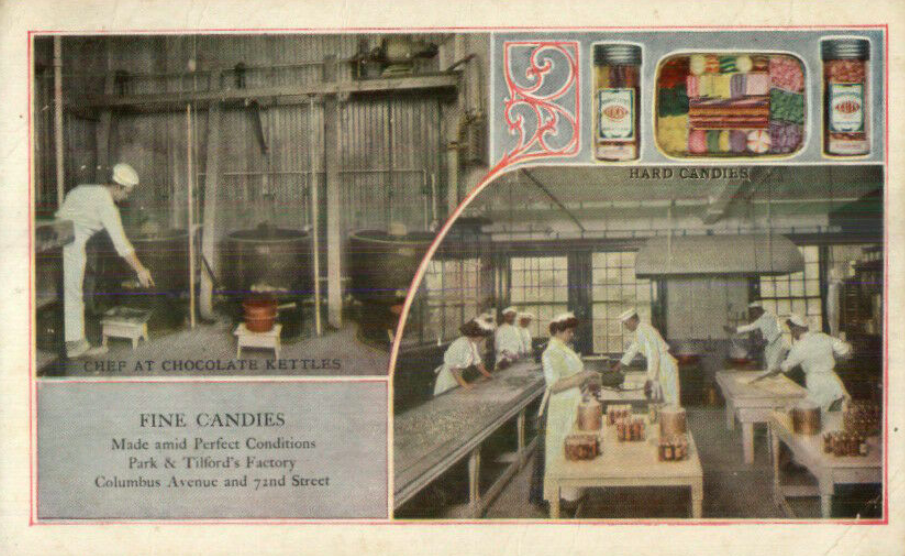

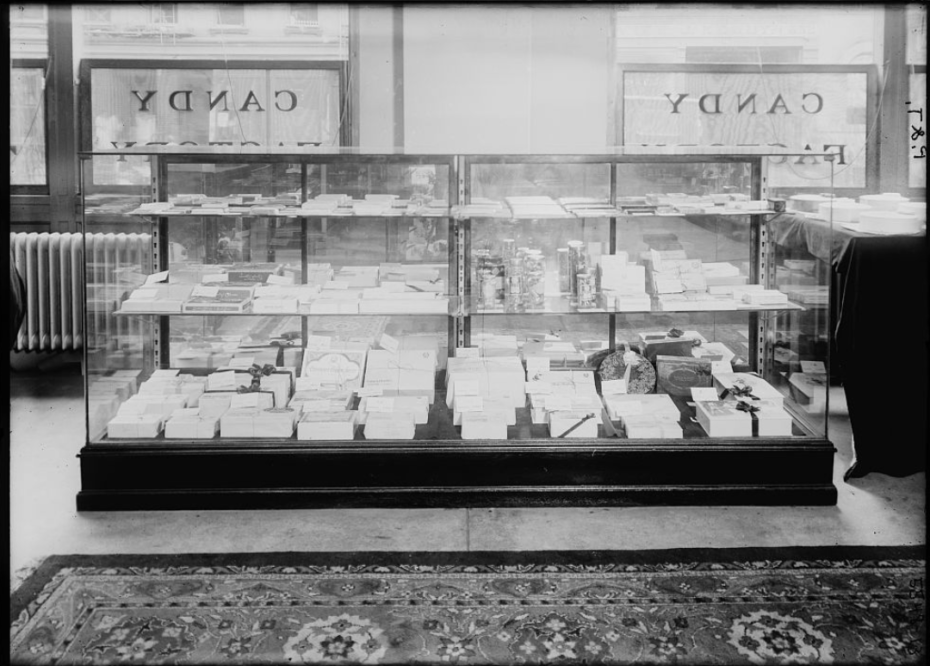

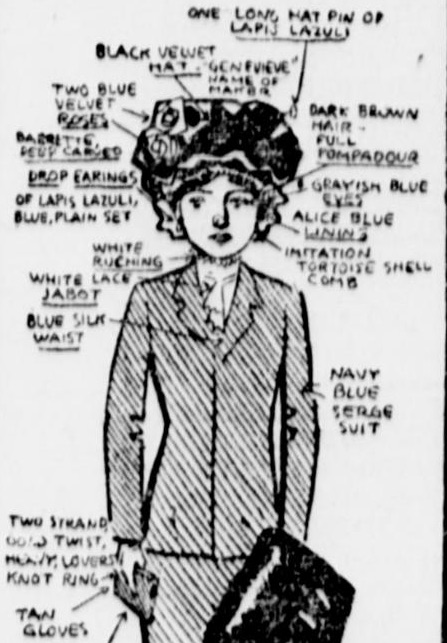

On that fateful winter morning in 1910, the official consensus is that Dorothy left 108 East 79th Street to buy a new dress at 11:00am. She had the present-day equivalent of about $600 (half of her monthly allowance), and walked to a fancy 5th Avenue sweet shop, “Park & Tilford’s Temptingly Delicious Chocolates & Bon Bons”, where she charged a box of chocolates to her account. Her next stop was Brentano’s bookstore, where she bought Engaged Girl Sketches, a humorous book. In fact, all reports of the clerks who engaged with her at both locations said she was very well spirited, not giddy, but quite normal, and pleasant. Even her friend Gladys King, who ran into her on 5th Avenue and 27th Street at 2pm, said she was in a good mood when they ran into one another. Dorothy said she was going to walk through the park. It was the last time anyone saw her.

As evening approached, Francis and Mary began to worry. They feared their daughter was up to some kind of scandalous business, but eventually broke down, called on her friends, and asked them for clues to her whereabouts. No one knew. Alerting their circle of friends meant inviting high society’s gossip mongers to speculate about a missing heiress. For the Arnolds, the fear of embarrassment and public scandal may have played a part in the decisions they took next. Denial, while just as tragic, goes down a little easier. When a friend named Elsa returned their call quite late at night to check in on Dorothy’s whereabouts, the Arnolds assured her that their daughter was home at last. Could she come to the phone? Not tonight, they said. She was under the weather after a day of shopping.

For the next two weeks, the Arnolds kept things under wraps, refusing to tell the police of their missing daughter. Their refusal to seek professional help during the first days of her disappearance spiralled the case out of control.

The Arnolds did a hire lawyer (but most importantly, a friend) named John Keith a day after her disappearance. Keith investigated all the local hospitals, morgues and jails. He even went to Boston and Philadelphia, but still, no dice. They finally brought in the big guns: the famous Pinkerton Detective Agency, whose agent interviewed Dorothy’s friends, acquaintances, and classmates, but again, no dice. Out of ideas, and options, they returned to the only place where they decided it was possibly to acquaint themselves with the most intimate side of Dorothy: her bedroom. That, Keith said, was an area where had found some troubling things…

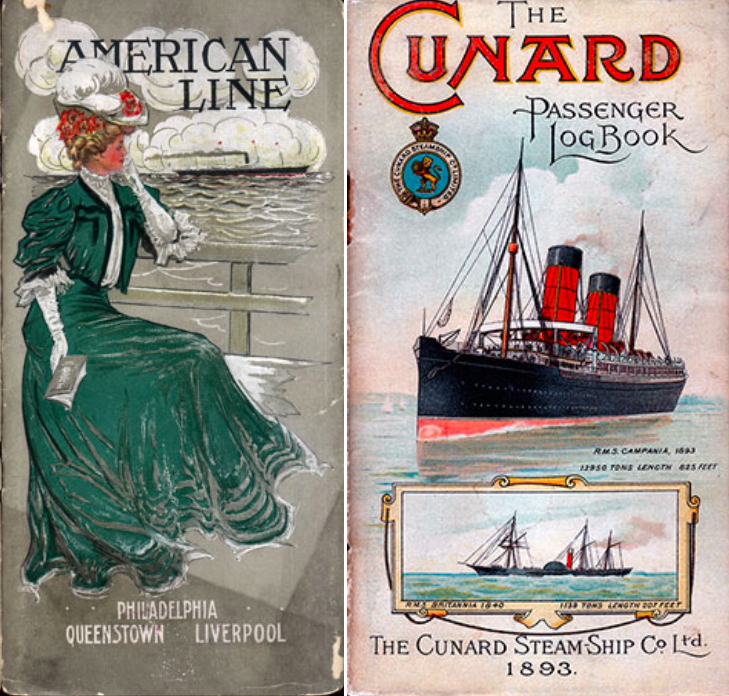

There were three telling discoveries in Dorothy’s room: recently burnt documents in the fireplace, pamphlets for transatlantic steam liner voyages, and letters with foreign post – a trifecta of intrigue if ever there was one. The burnt papers were confirmed as Dorothy’s rejected manuscripts, one of which she had recently received back. If the steam liner brochures were anything to go on, maybe she thought a change of scenery would help.

There are a few things to consider about the state of Dorothy’s room. For one, we can never be certain it was Dorothy who threw her work into the fire. Nor can we assume the steam liner documents weren’t planted by someone else; her parents? or the lawyer who was employed in their service?

Did Dorothy simply run away? It would be a classic middle-finger move to her overbearing parents. Or perhaps she was skipping town with some European lover – another theory that made Mary and Francis hot with embarrassment, but that they had no choice to chase. The Pinkerton agency thus took their investigation overseas, looking into recent marriage records and checking the passenger logs of recent steam liners. Yet again, they came back empty handed.

When the Arnolds finally divulged the predicament to the NYPD, admitting they’d waited to tell them, the force assumed they meant a matter or days, maybe a week. In reality, six full weeks had passed. At this point, the case needed some big publicity to get the ball rolling again. So much to their chagrin, the Arnold’s were asked to hold a big press conference to announce Dorothy’s disappearance, and a $25,000 reward for any tip-offs. It was precisely the spotlight they never wanted. Now, it was shining twice as harshly.

For the parents, responding to the reporters was like pulling teeth, especially when they began inquiring about the possibility of Dorothy having run off with a lover of a lower social standing. At that remark, Dorothy’s mother snapped back, making a longwinded statement about her daughter’s poor choices in love and “lazy” men. What she really meant, was men like George Griscom, Jr.

George is the indispensable, star-crossed lover of our mystery. He was an engineer almost twice Dorothy’s age, who had met her in college. Now, George was a wealthy Pennsylvania boy, so his social standing wasn’t the problem for Dorothy’s parents, but his social etiquette was. Potential husbands shouldn’t convince young women to pawn their family’s items for a steamy hotel meet-up. At least, that’s how Francis and Mary felt about the first time Dorothy had disappeared to live with him for a week at a hotel in Pittsburgh. Unfortunately, she wasn’t very discreet about it and “borrowed” the modern-day equivalent of $12,000 in family jewellery to cover her travelling costs, but only pawned them for about $1,500. The Arnolds were furious that she had blown their money on this middle-aged, deadbeat love interest who still lived with his parents. They forbid her to see him, but she did anyway, one last time before she disappeared for good – which just so happened to coincide with George’s own departure to Europe with his family.

It was Dorothy’s mother who decided to track down George overseas. Accompanied by her brother, she knocked on his hotel room door in Italy for answers, but she was given none, or at least none that satisfied her. Up until now, he said, he had no idea she was missing. When Mary insisted he give her all letters of correspondence between them, he also refused, insisting he’d disposed of them.

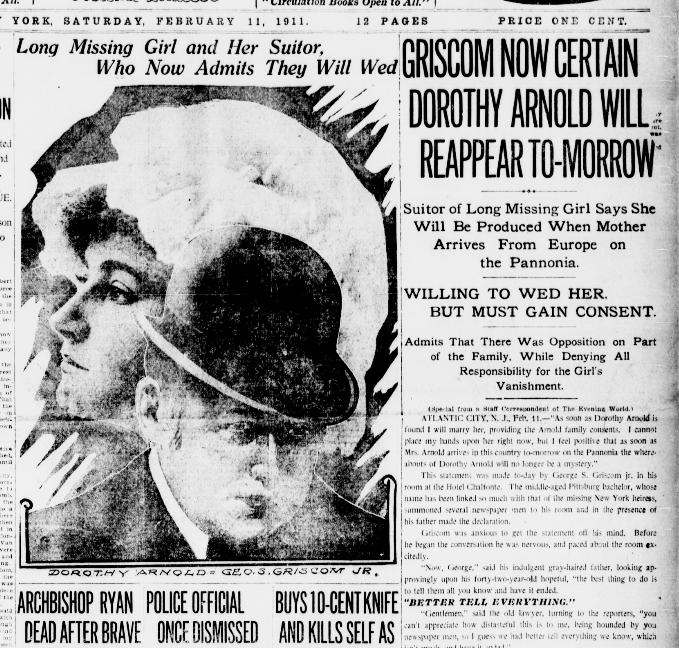

George remained in Europe for another month, but eventually had to give his own press conference upon returning to America. The speech was as you would expect, filled with talk of affection and worry for the young woman, praise for the police, etc. The cherry on top, however, was when he declared his plans to marry Dorothy upon her return. The public loved it. Mary and Francis, however, weren’t having any of it.

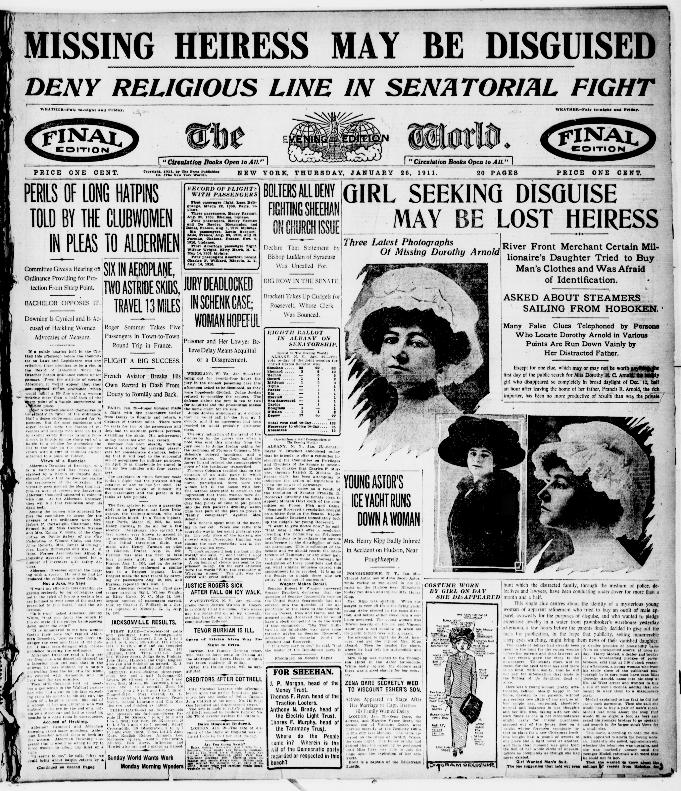

As the weeks wore on, the case grew worse than cold, it grew stale. The public theories were many, and even when the case was closed 75 days later, it grew more and more absurd. Two months after she went missing, the Arnolds received a postcard from New York saying “I am safe – Dorothy” but nothing more. The sightings and fake ransom notes came flooding in, with Dorothy becoming more and more of a public fascination across the country — which begged the question: what kind of woman was Dorothy, really?

If there was one thing we can be certain Dorothy was passionate about, more so even than we can be sure she even loved George, it was her writing career. Or rather, lack thereof. The blow of her first story getting rejected from a publishing company was hard enough on her, but the second was unbearable. To make matters worse, she felt she had few champions behind her given her parents’ negative attitude, and had to keep a secret PO box for sending and receiving mail about her work. When her second short story, “The Poinsettia and the Flame” was rejected by McClure’s magazine, it seemed that something broke in her. George, after weeks of claiming his correspondences with her were gone, surfaced a letter in which she wrote, “Failure stares me in the face. All I can see ahead is a long road with no turning.”

It was disheartening, vague evidence at best. The investigation had reached a tipping point for everyone’s sanity, but especially for her parents who said it was time to face the music: their girl had been murdered. The NYPD, however, begged to differ and continued the search. Call it a classic glass-half-empty-or-full perspective, but the police saw the lack of evidence for her death as proof of her living.

In an effort to bring things to a close, Dorothy’s father said he thought she’d been killed and disposed of in the Central Park reservoir – not likely, said the police, as the lake was frozen at the time of her disappearance. Still, they checked. The very notion that Dorothy had made it to the park was mere conjecture; the last time she was seen was on a busy street in a part of town with an extremely low crime rate. It simply made no sense to the media, the public, and the police. It would’ve made more sense if she’d just evaporated into thin air.

There is another part in Dorothy’s aforementioned letter to George that raises an eyebrow. After mentioning her metaphorical, “long road with no turning,” she writes, “Mother will always think an accident has happened.” What accident? What had, or was going to happen? For Keith and George, suicide was one strong guess, but it was so taboo that the parents wouldn’t even consider it. For the gossip columns, the “accident” evoked the involvement of something called, “The House of Mystery.” That’s where two the two dominating theories of her disappearance come into play.

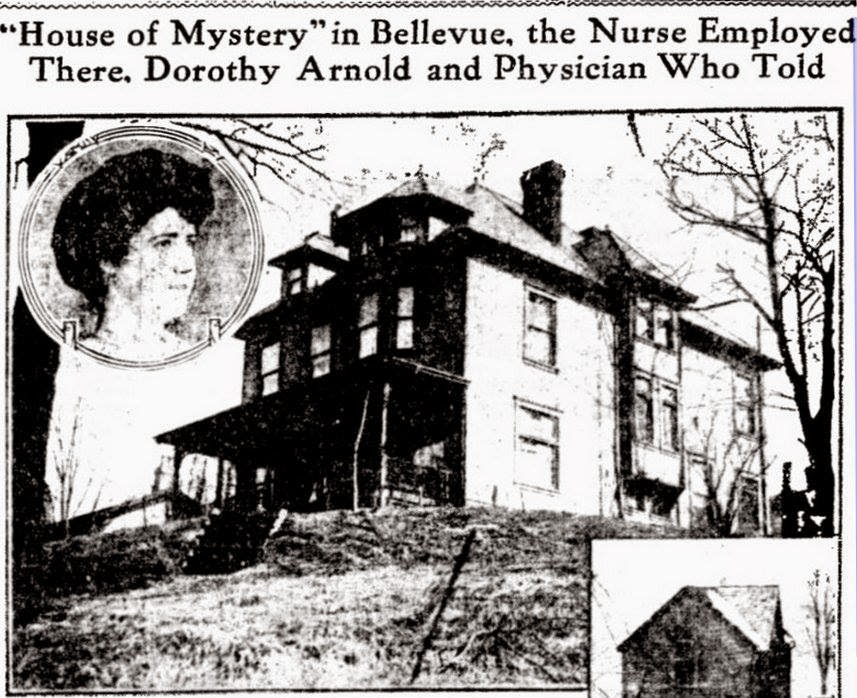

The “House” was an underground abortion clinic that, some time later, was revealed to have welcomed various women into its doors who often “disappeared”. The doctor who ran the clinic, Dr. Meredith, would later claim to have performed a procedure on Dorothy that took her life, as the conditions, he argued, were simply so shoddy that complications and deaths amongst patients were inevitable. When women died, they were burned in a furnace, and Dorothy would’ve met the same fate.

It satisfied the NYPD, but not George or her parents (the only time they would ever agree). George, however, also wasn’t fond of another explanation that surfaced, and put him in jeopardy: the “Little Louie Theory.” In 1916, a man named Edward in a Rhode Island prison said he was paid to dispose of a woman’s body the same year Dorothy went missing. He said he was hired by a man called Little Louie, and made to drive a female body from New Rochelle, to West Point. From there, they met up with a well to do man who went only by “Doc,” but who said that the dead woman’s name was in fact Dorothy, and that she had died from an operation at home. Edward said they cocooned the dead body in saran wrap, and left it in the cellar of an abandoned home.

Was “Doc” a man from the clinic? A kidnapper? When it came time to for Edward to describe him to the police, the description actually resembled George. Still, no bodies were found in Jersey, and the police took George’s word over that of the felon, even if, as some thought, he might have paid them off.

When Francis died, his will said nothing of Dorothy. When her mother died, she was still hopeful. Then there was Keith, the family lawyer who’d been there from day one of the mystery, who finally felt he was able to pitch his two cents about what had happened now that both parents passed: Dorothy, distraught from her failed career, took her own life. George agreed. As baffling as the case remains, it helped inaugurate the new era of intense, but extensive crime press coverage that we expect from our news sources today. The tale also endures as a reminder of the gross disparities between the attention the media and police do and don’t give to certain cases — as evidenced by how much leeway they gave to Dorothy’s upper-class parents, who effectively withheld information and handicapped the case’s chances from the beginning. Regardless, the public continued to spin sightings and stories out of thin air about the missing Manhattan Heiress, who grew into a sort of morbid mythology as time wore on. Some preferred to imagine her living out her days laughing at the press from afar, on a boat in Greece, or a cabin in California. A hundred years on, the mystery is still waiting to be solved.