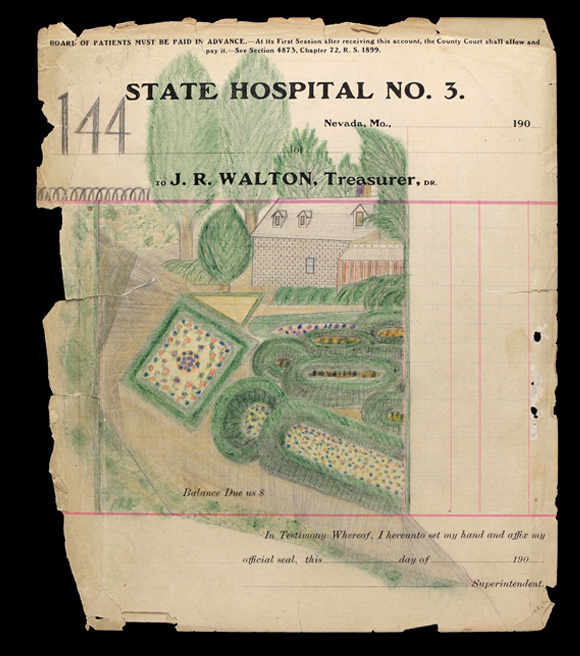

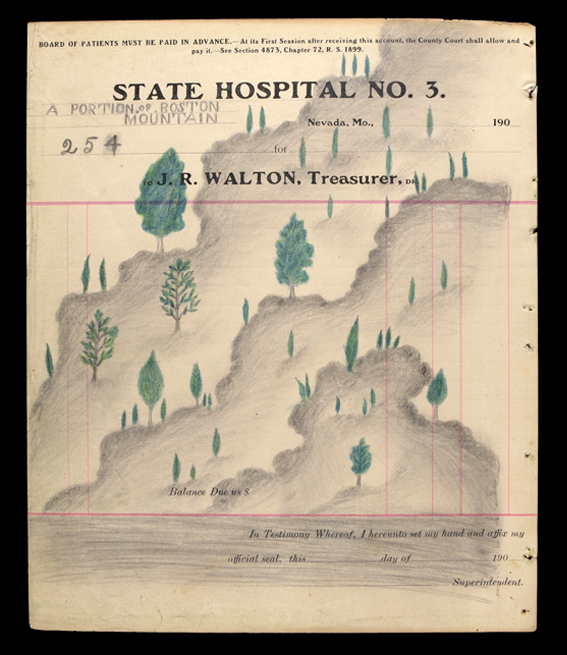

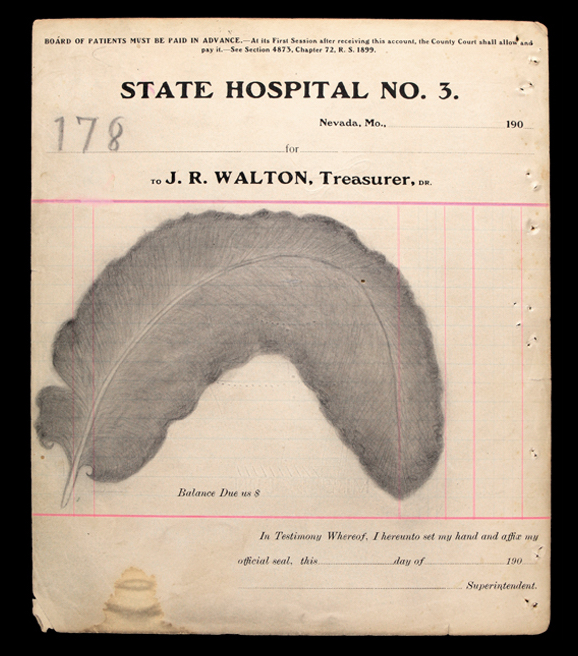

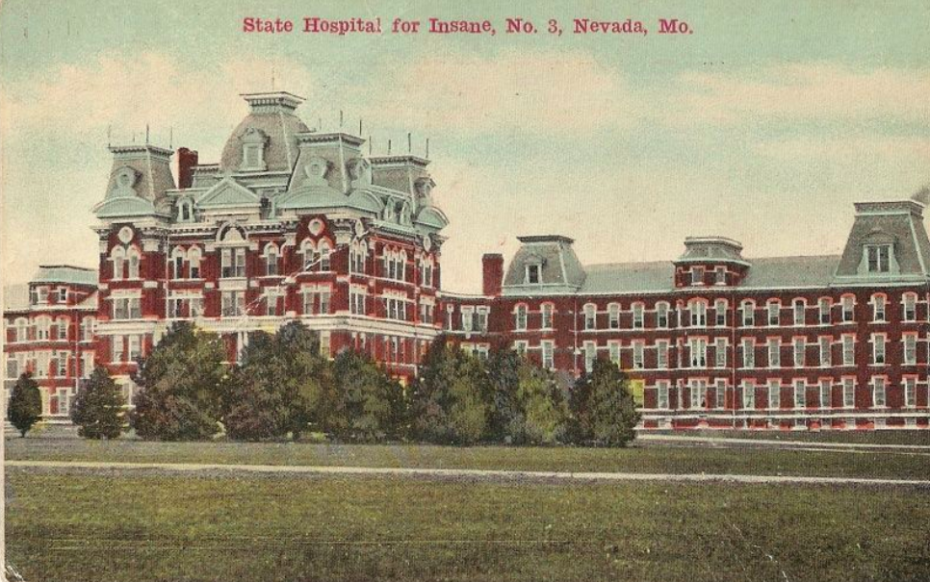

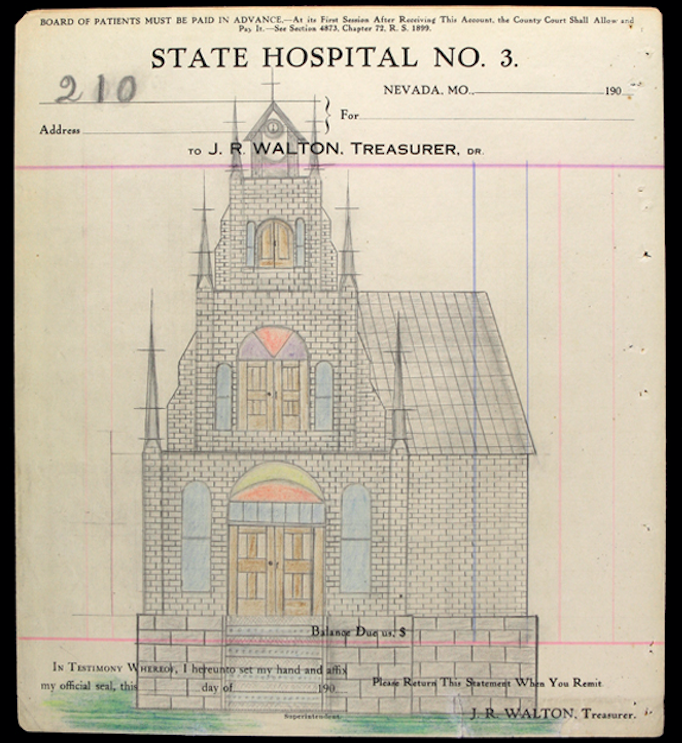

Drawings, found in the hundreds, every page hand-bound, every artwork a labour of love. Why was it found in a dumpster in Springfield, Missouri, by a teenager who pulled it out in 1970? For decades, the only clue to its origins was a water mark: “Missouri State ‘Lunatic Asylum’ No. 3.”

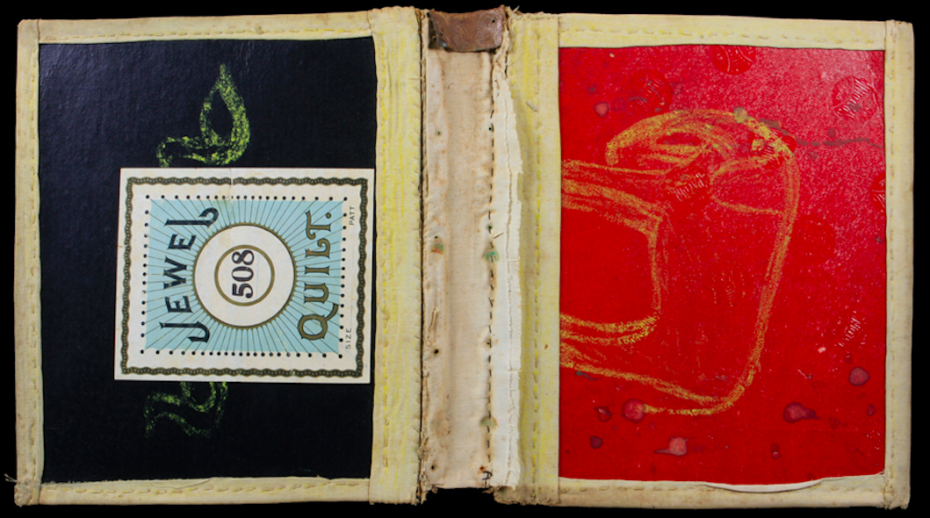

These drawings weren’t an afterthought. They were 300 pages of someone’s life. The dumpster-digging teen who’d made the discovery waited more than three decades before he decided to sell the book on eBay in 2006, when a collector in St. Louis didn’t hesitate to snatch them up for $10,000. Today, a single page fetches around $16K at auction.

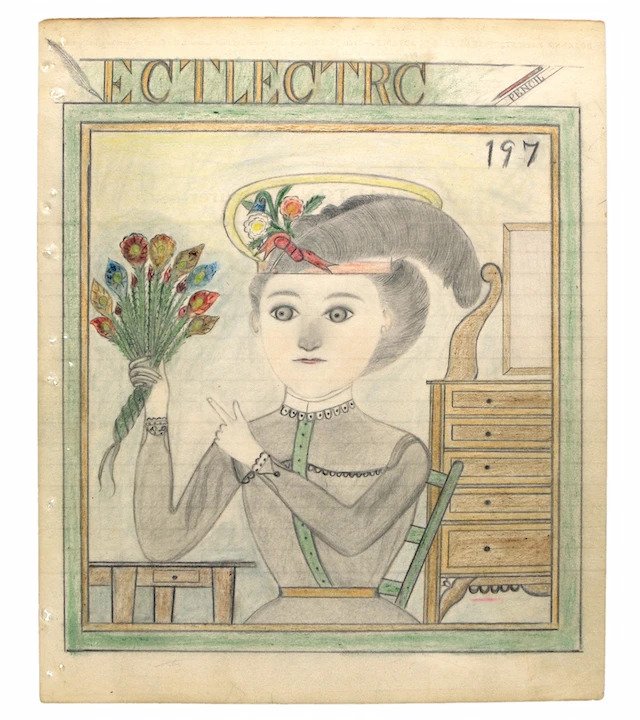

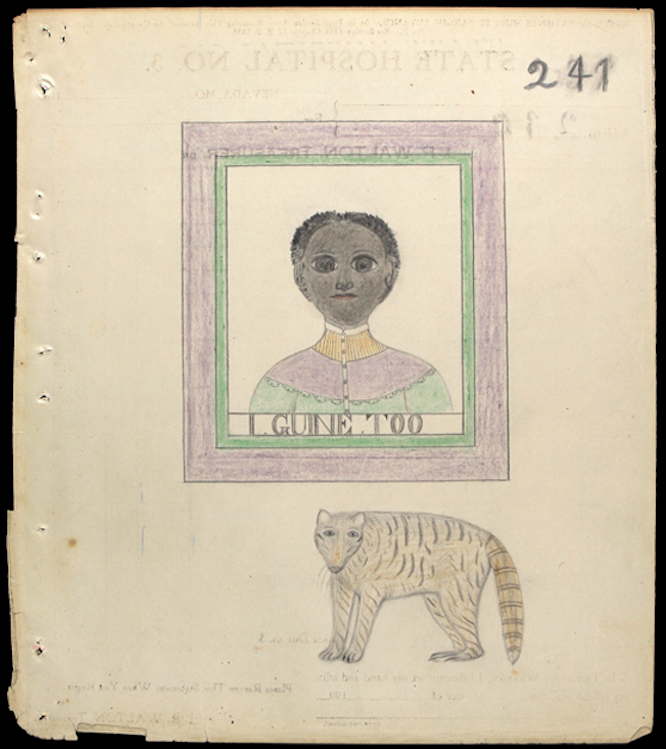

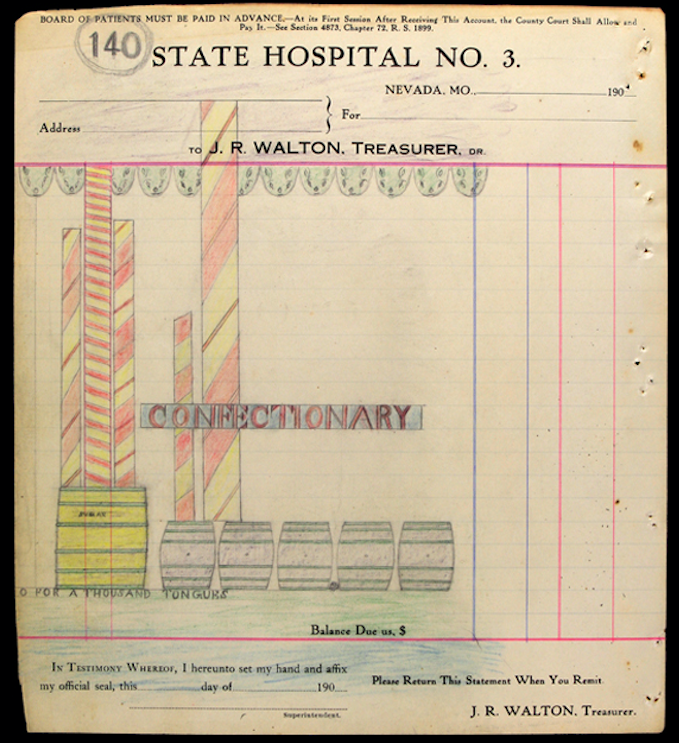

Who was the artist – or, artists? The element of mystery only added to public intrigue. The St. Louis collector in turn sold the notebook on to New York City collector Harris Diamant, who decided to call the mystery artist “The Electric Pencil” due to the letters “ECT” on some of the drawing – electro-convulsive therapy.

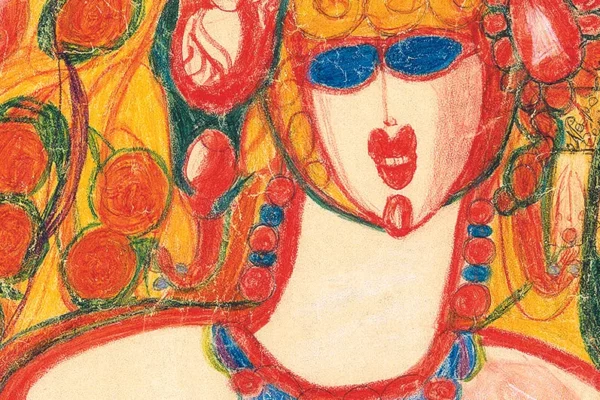

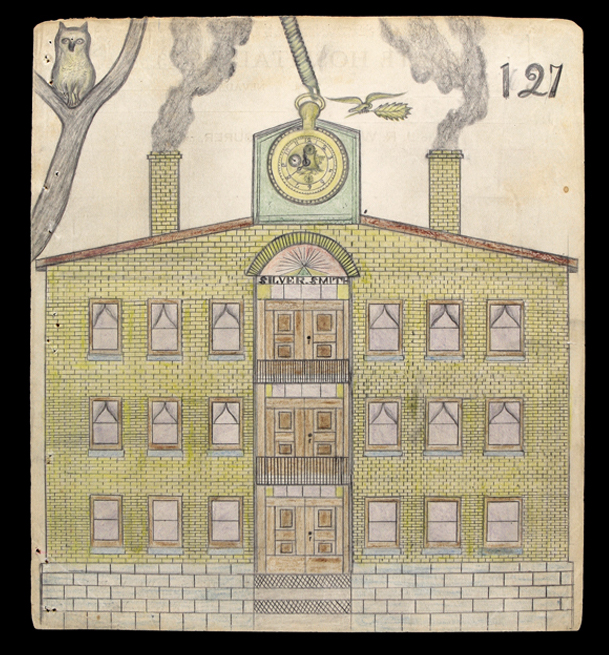

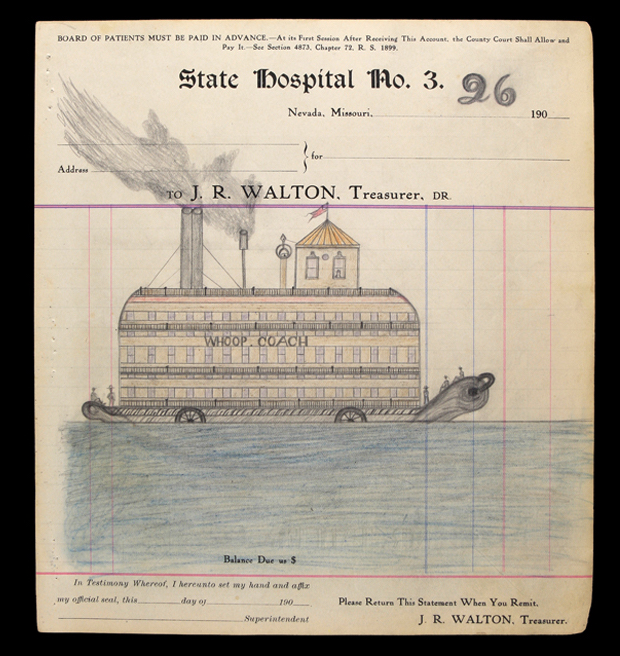

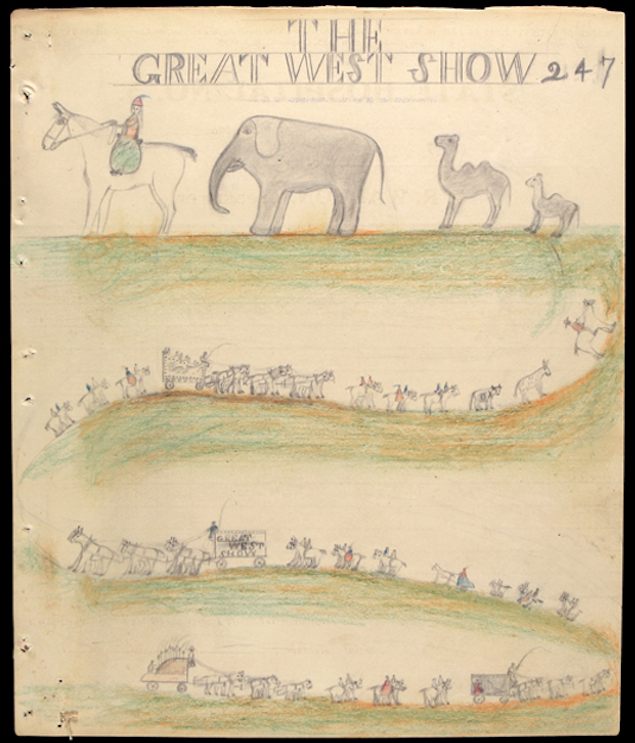

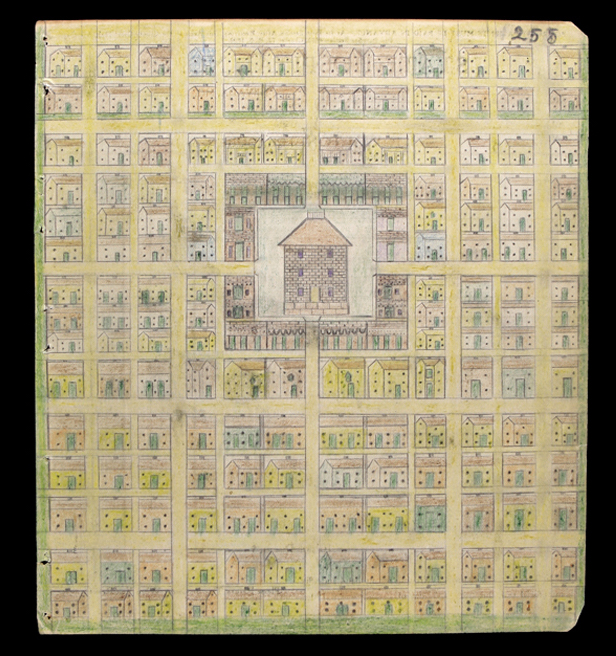

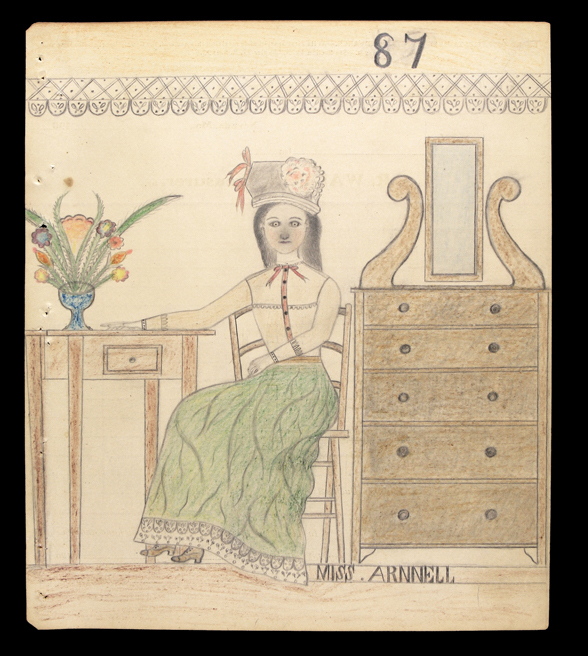

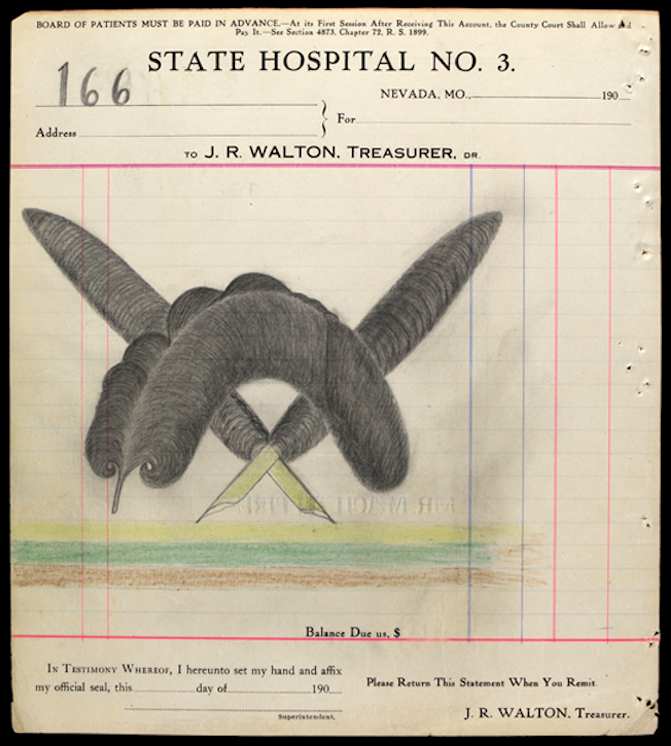

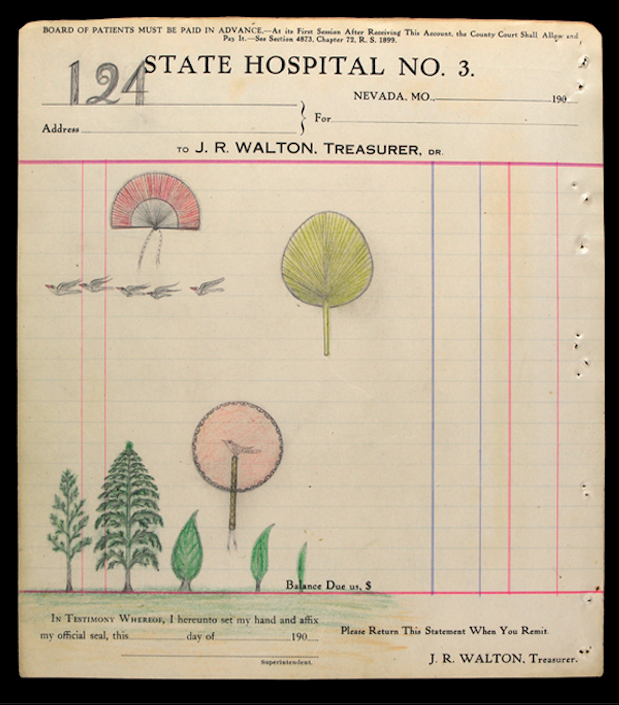

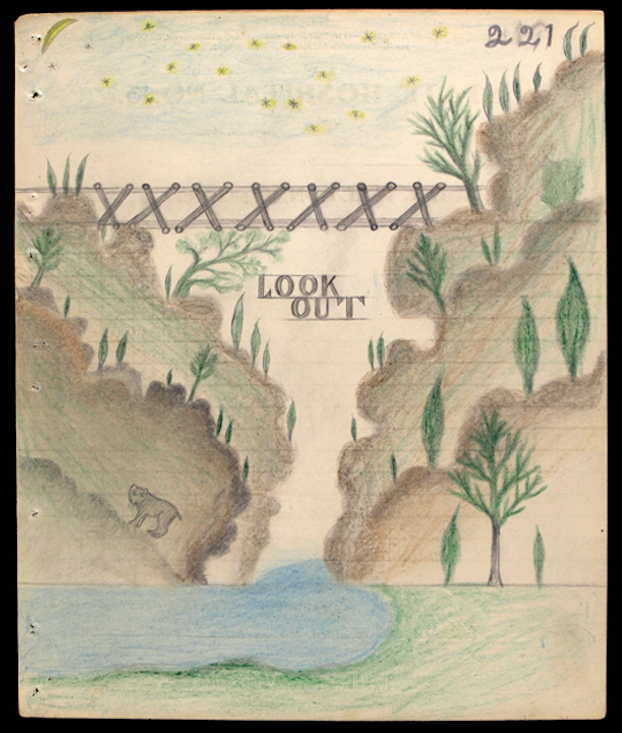

Dark things had been happening inside the hospital, which was long gone by the time Diamant was investigating the Electric Pencil Artist. Today, we know that it was underfunded, understaffed, and a breeding ground for caretaker and patient abuse. The colourful notebook was likely one patient’s coping mechanism. Compiling a nameless portfolio of wide-eyed Victorians and baby blue rivers; circus animals and steamboats, the notebook was both impeccable, and troubling.

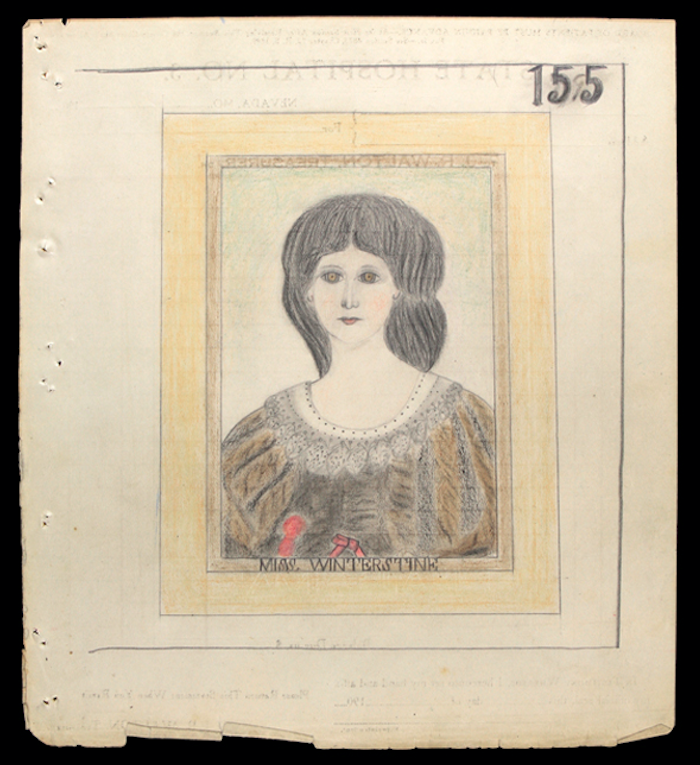

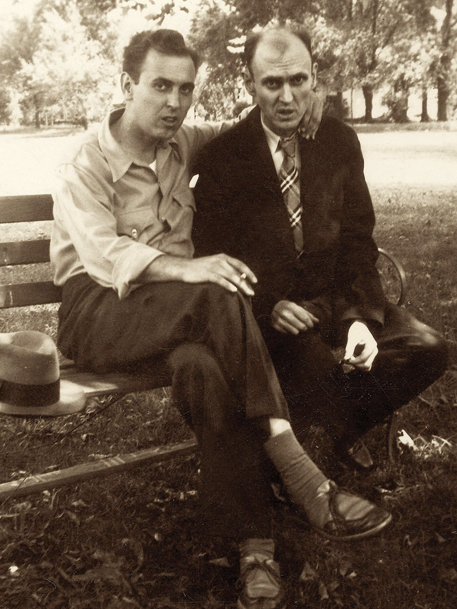

In search of more clues, Diamant decided to run some of the drawings in Missouri’s most prominent newspaper. Amazingly, a woman named Julie responded to the feature with a name: James Edward Deeds, Jr. He was her uncle, and her mother’s portrait, along with her name, Martaun, was in the notebook. The notebook was treasured by the Deeds family, who were distraught to have lost it in the shuffle of moving houses. Hence, we arrive at the dumpster c. 1970, and reach the full circle of our story. Forty one years after their discovery, the drawings finally had a name.

“Edward,” as folks called him, was a sweet boy – and never really cut out for the hardness of farm life that awaited his family upon return from Panama, where he was born in 1908, to the United States. He was autistic but misdiagnosed as schizophrenic. It was his father, who beat him regularly, that placed Edward in the asylum for life after an incident where Edward allegedly threatened his brother, Clay, with a hatchet. According to his brother, however, the whole thing was a tragic misunderstanding of which their abusive father took advantage. Edward and his brother Clay remained close until the former died in 1987.

But why was Edward, a man drawing in the 1930s, dreaming up Victorian Era figures long before his lifetime? There’s a childlike style to his work, but it also separates itself from some of the usual Outsider Art attributes.

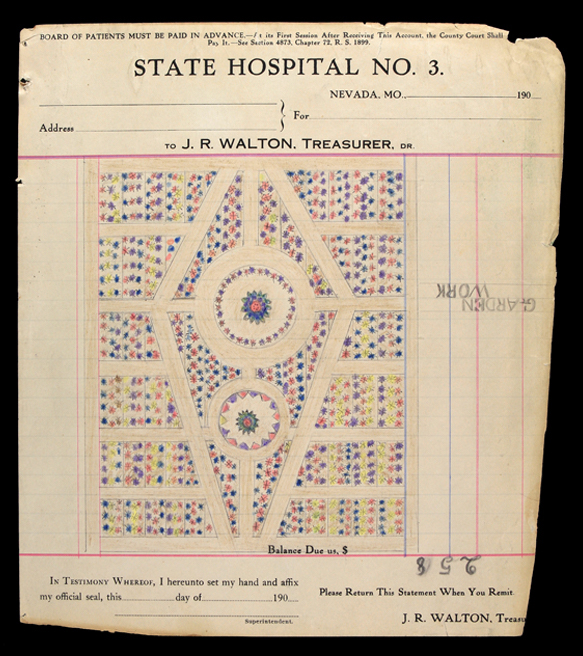

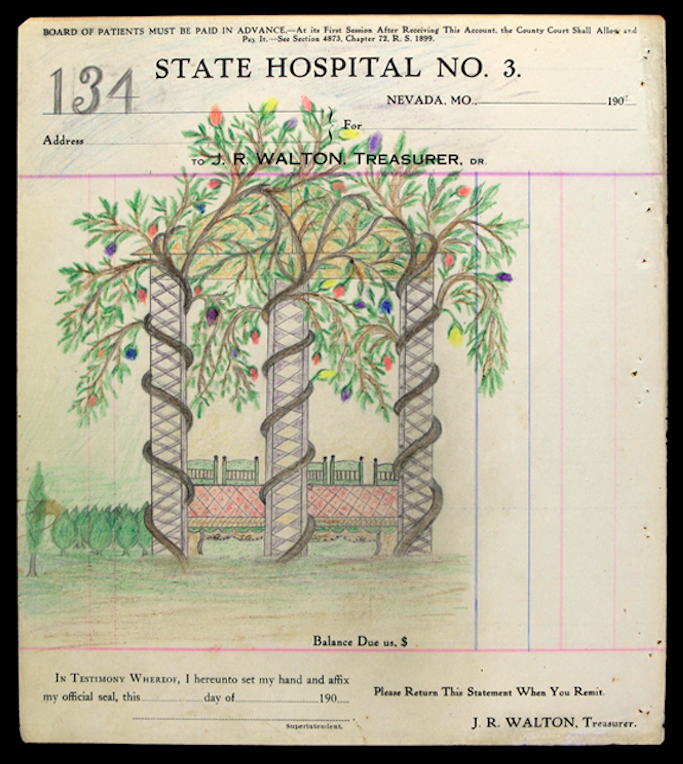

There are no frenetically overdrawn pieces, no psychedelic patterns fighting for space on the paper. The lines are tight lipped, charmingly meticulous – as if they could’ve spilled out of Wes Anderson’s briefcase. They’re patient.

They remind us of the drawings from another world, similar to that of Outsider Artist Henry Darger’s fantastic saga of the “Vivian Girls”. Yet, these works don’t have any of Henry’s dense, war-torn foreground. Edward’s work is mainly circus tents, parading animals and steamboats; prim gardens, feather hats, and factories. Is it a precision that brinks on obsession? Control?

Alas, this is where the holes come in. Pinning Edward as the artist doesn’t mean we understand his oeuvre, or life, completely. He left no written memoirs behind. His notebook holds the only clues that tether him to a reality beyond the drawings – depicting a family member here, or a reference to a doctor that was likely administering electroshock therapy.

All of this makes it impossible to draw any weighted conclusions, but perhaps it’s for the best that Edward’s legacy should live on in the imagination. The gallery that now handles his work does so with care, and has helped release his work in a book called, The Electric Pencil: Drawings from Inside State Hospital No. 3. There have also been whispers of an upcoming documentary on the artist.

Discover all of Edward’s drawing in this digital archive.