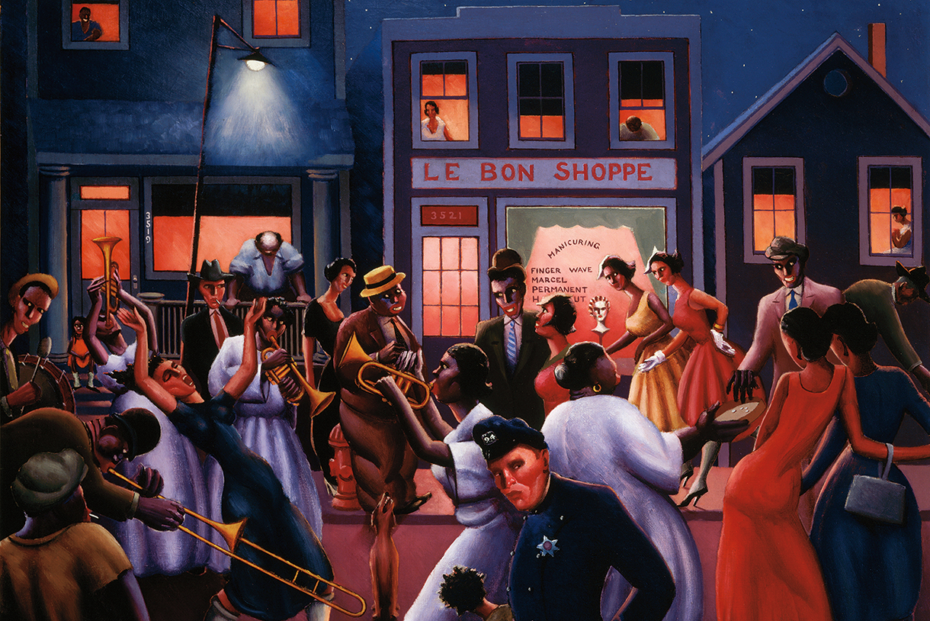

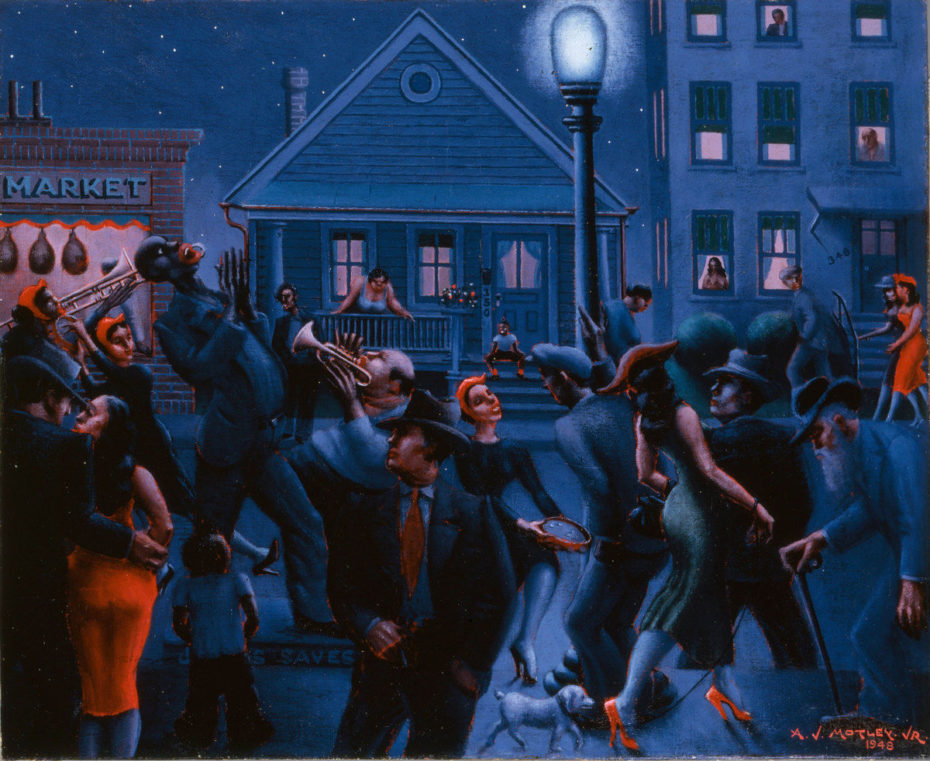

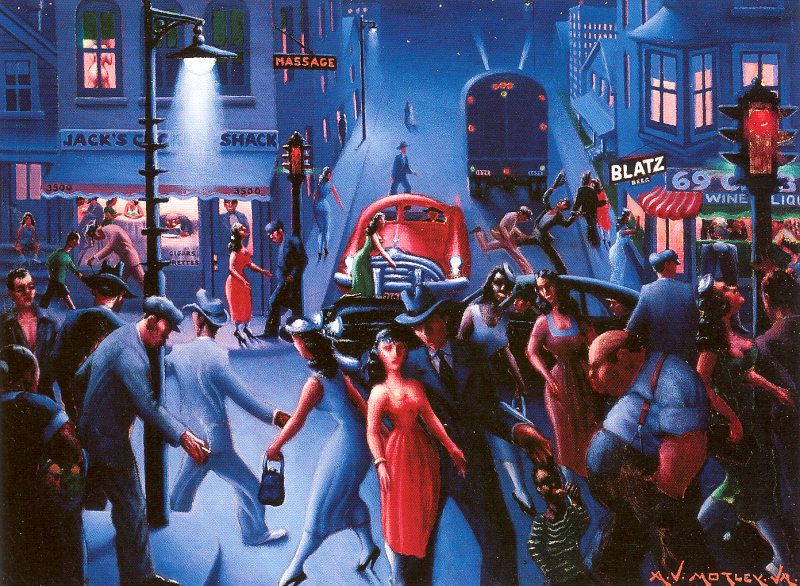

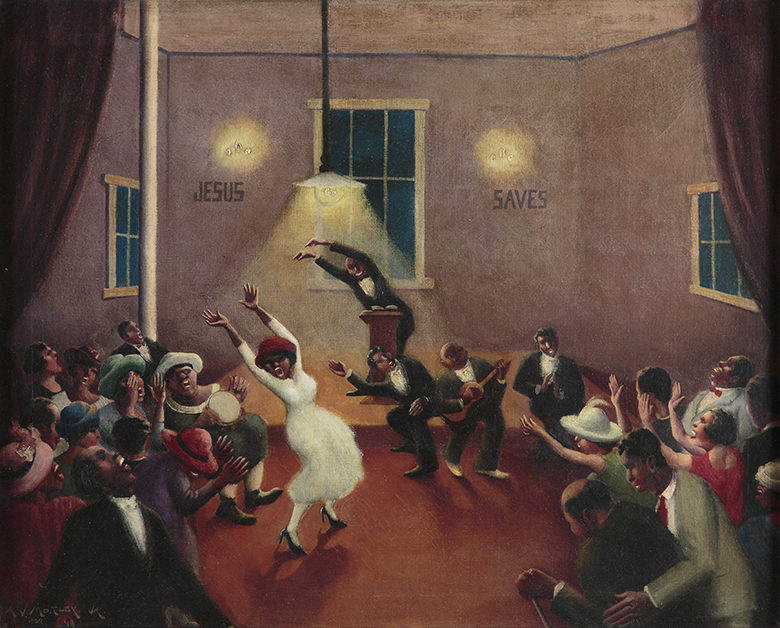

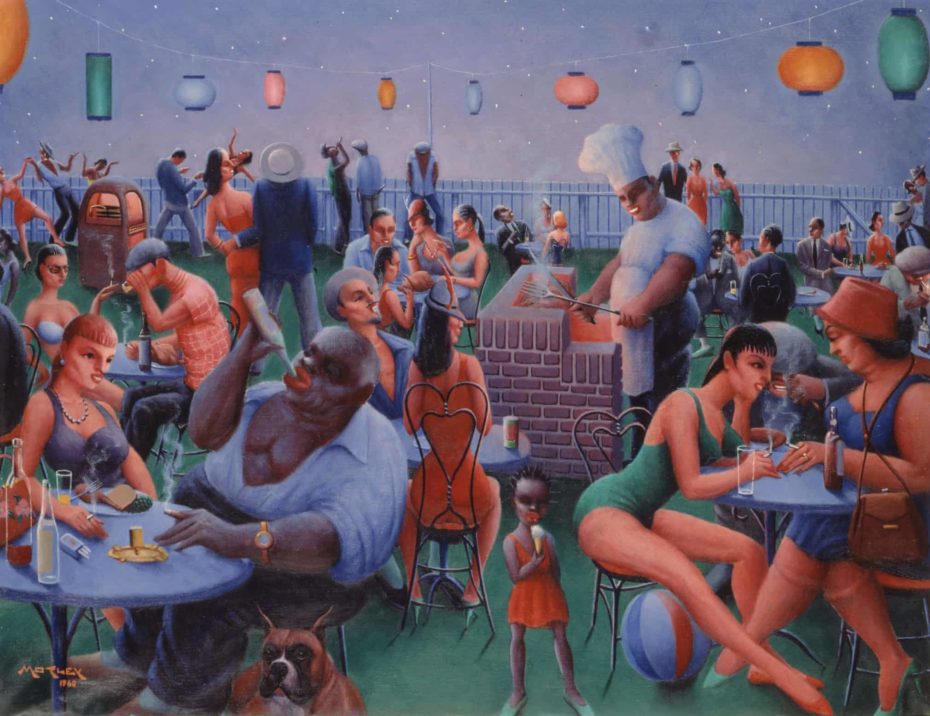

You can almost feel the rhythm of the music through his paintbrush. Archibald Motley was one of the only artists of his time willing to vividly and positively depict African Americans in their vibrant urban culture, rather than in impoverished and rustic circumstances. Skin tone is celebrated as something diverse and inclusive in his work. He put the beauty, achievements and cultural variety of blackness on display, becoming one of the major contributors to the Harlem Renaissance. Giving us Modernism to rival Matisse, nocturnal intrigue reminiscent of Edward Hopper and an electrifying taste of the Jazz Age all at once, this is the seductive artistry of Archibald Motley…

Motley became the first African American to have a one-man exhibit in New York City. His grandmother was a slave who had been taken from East Africa, but he had grown up in a predominantly white, racially tolerant neighbourhood in Chicago’s south side. Motley was mixed race and understood he was raised among an affluent and elite black community.

The jazz-influenced paintings portrayed a community that he was not part of and Motley wrestled all his life with a feeling of disconnection with the African-American community. He felt neither black nor white, consumed and conflicted by his racial identity. But this positioned him perfectly as an advocate for social change. Archibald wanted to live in a world without racism, where everyone could enjoy life without thinking about the colour of their skin.

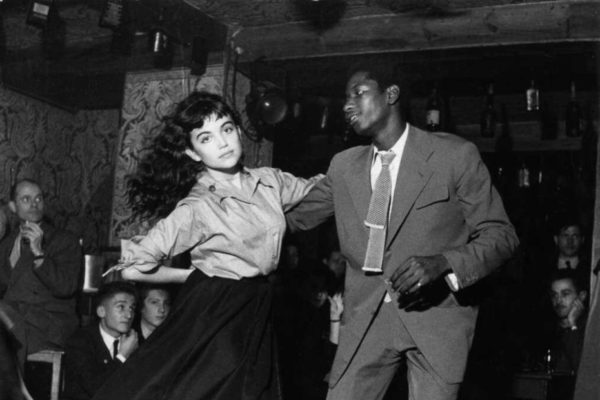

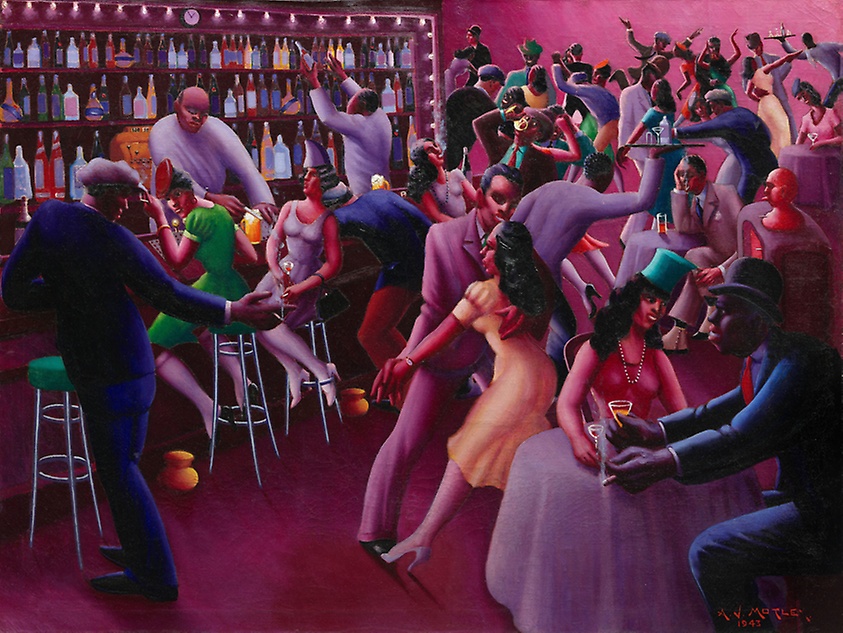

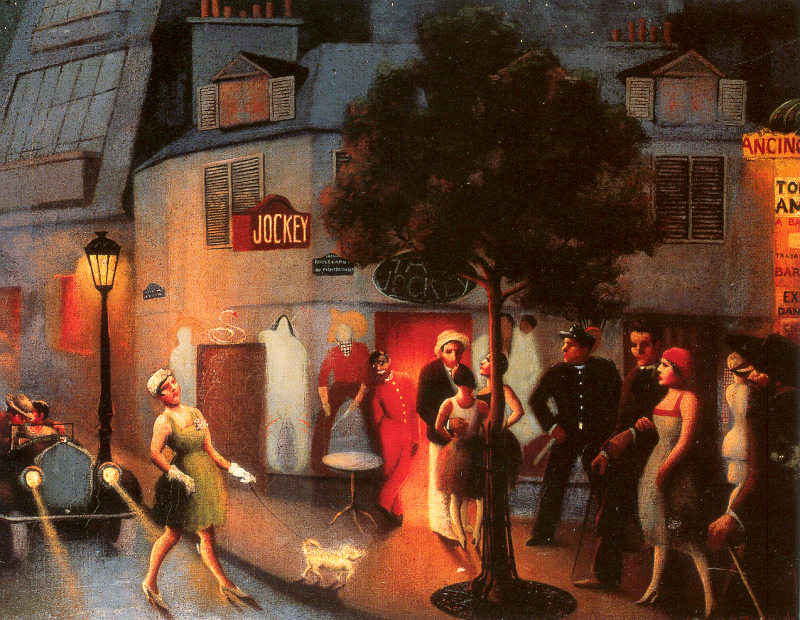

In order to this, he used his mixed ethnicity to place himself in the middle, asking white America to see what he saw as a spectator of the Harlem Renaissance. With access to both worlds, he was able to portray African American nightlife as an inviting and infectious scene that appears to have forgotten racism while enjoying and dancing to jazz music, making the most of life.

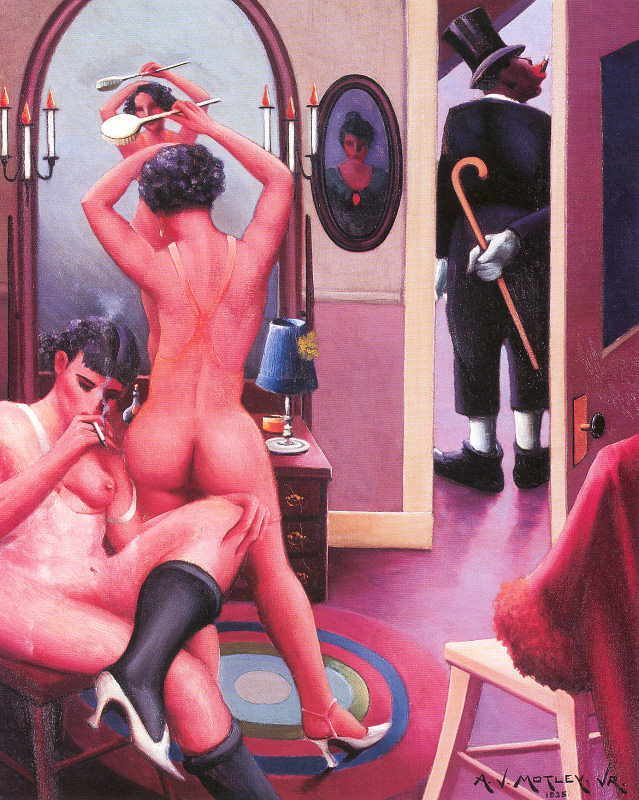

If you’ve found yourself struggling with the caricatured facial features of some of Archibald Motley’s subjects – you’re not alone – so are we. Highly controversial to the modern eye, some of the subjects resemble minstrel figures or golliwogs. But we’re reminded of Patrick Kelly, the late African-American designer from the 1980s who made blackface his brand by deliberately incorporating a visual interpretation of the golliwog into his patterns.

Art historians argue that similarly, it was never Motley’s intention to stereotype his subjects for a white audience, but quite the opposite.

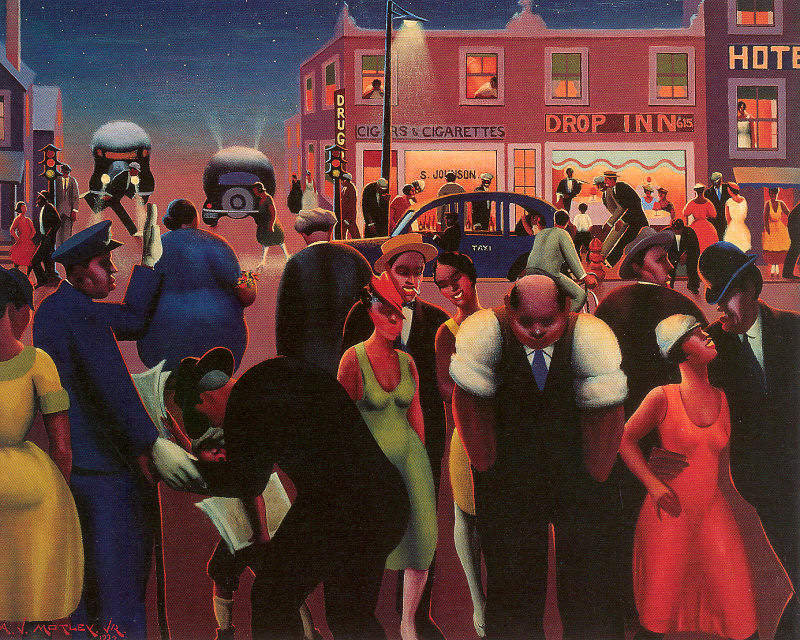

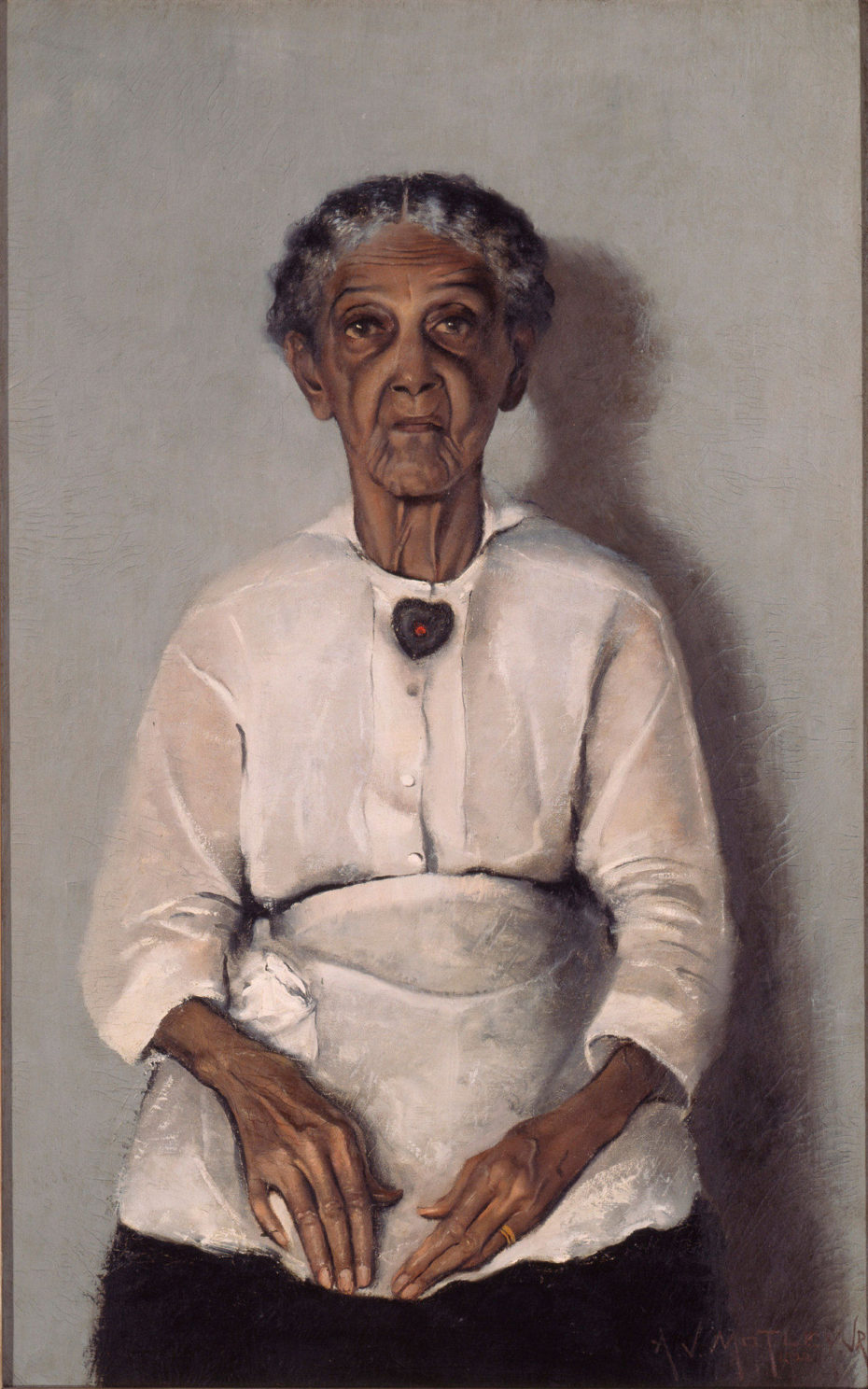

“They’re not all the same color, they’re not all black, they’re not all, as they used to say years ago, high yellow, they’re not all brown,” Motley points outs to the Smithsonian in an interview in 1978. “I try to give each one of them character as individuals”.

In the midst of the shaping of black cultural and economic freedoms, it’s understood that Motley used this racial imagery to tackle inequality in pre-Civil Rights America, asking his white audience not to categorise African Americans as one stereotyped race, but as diverse people, each one an individual character worth getting to know. The vast array of skin colours in Motley’s paintings serves to contradict the stereotyped images and highlight differences in personality.

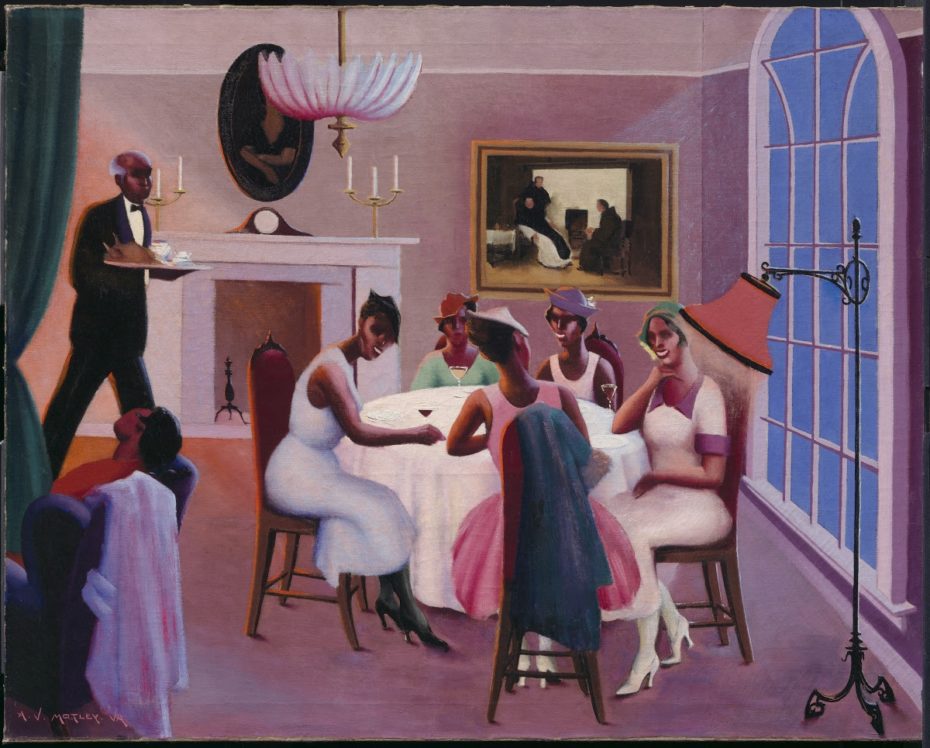

Thanks to his elite upbringing, Motley knew he could speak to both the black and white community and hoped to educate his audience on the politics of skin tone. The message to white America was: look at the beauty, achievements and cultural richness of African Americans. For black America, he wanted to show how their own diverse racial identity was something to be embraced.

Most importantly, segregation is not present here. Everyone is dancing together and having a grand ol’ time. Dark-skinned men are dancing the Lindy Hop with light-skinned women. Their skin is pink, magenta, blue-black and the infectious rhythm can be felt in their flailing arms. This was the progress of the Harlem Renaissance encapsulated.

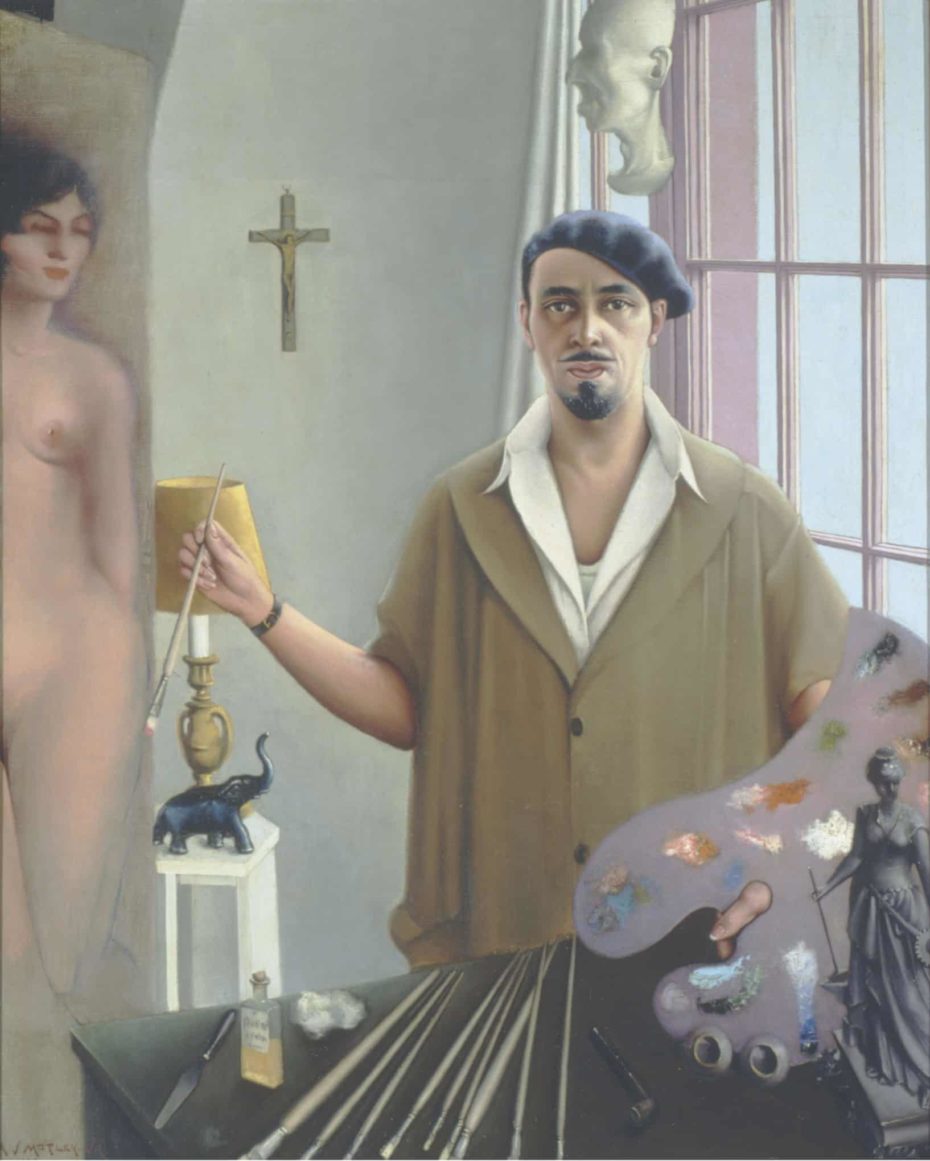

Motley would go on to become the first black artist to have a portrait of a black subject displayed at Chicago’s Art Institute. He could paint like a master painter, and had won a Guggenheim fellowship that sent him to Paris where he portrayed an African movement in the crowded cabarets and winding streets of Montparnasse.

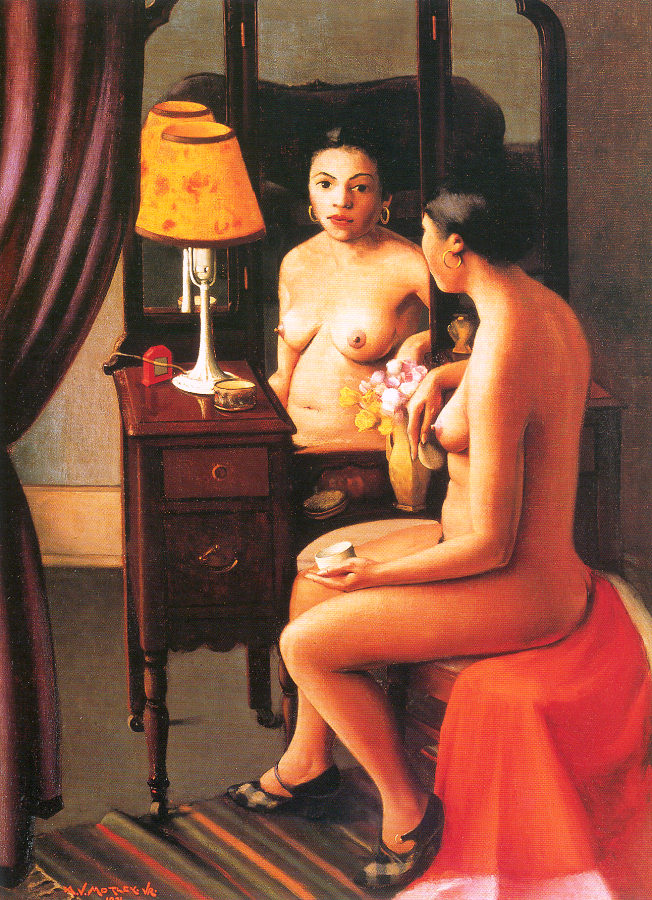

With a portfolio of work that dates from 1919 through 1960, Motley also painted extremely refined portraits that didn’t shy away from the sensitivities of the time, treating his art almost as a personal study in the different gradients of race.

He was inspired by the classical and Renaissance painters he’d seen at the Louvre, which can be recognised in his earlier portraiture work, but Motley later broke with academic convention and found his calling as a Jazz Age Modernist, becoming one of the most notable artists of the Harlem Renaissance.

And yet, in the context of American modernism, Motley’s name rarely comes up. By the 1950s, he was living in relative poverty, painting shower curtains for a living. Possibly one of the most underrated and misunderstood artists of the 20th century, some of his most important works now remain in private collections. While your digital screen can do no justice to Archibald Motley’s work, perhaps you’ll find something in his paintings that prompts you to share and help strengthen his name in contemporary art history.