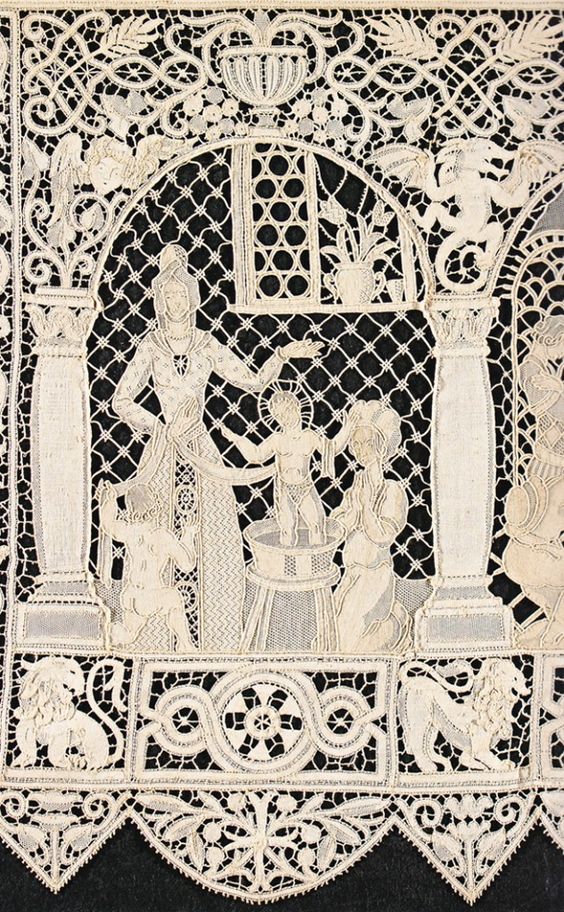

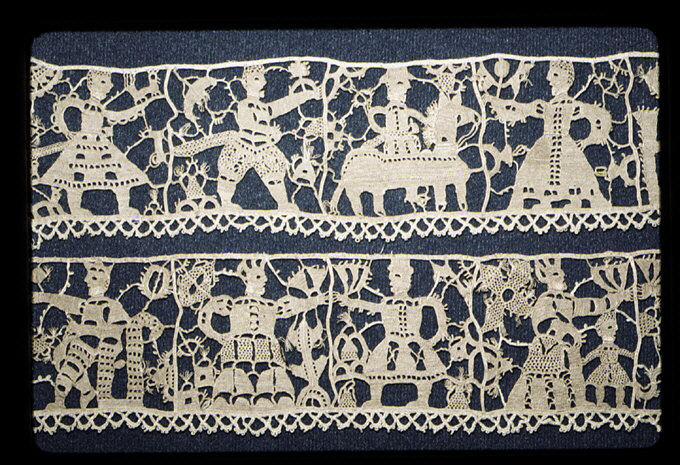

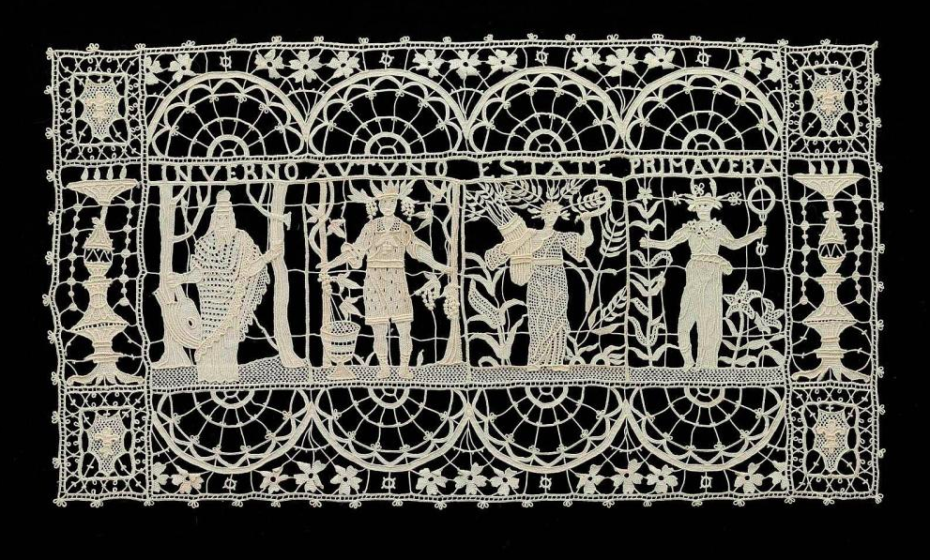

They were like snowflakes spun from silk, sought after just as feverishly as gold on the black market. Whether they were twisted with pearls or tied with silver knots, no two pieces of lace were the same in 1765. All too often forgotten in dusty attics today, for centuries, lacework was all about how you flaunted your individuality. Lace helped you tell a story by weaving a veritable comic book strip of characters on the cuff of your sleeve. From biblical tales to mythical beasts, eternal flowers and chivalric scenes, let’s take a little walk through history’s best pieces of coded couture…

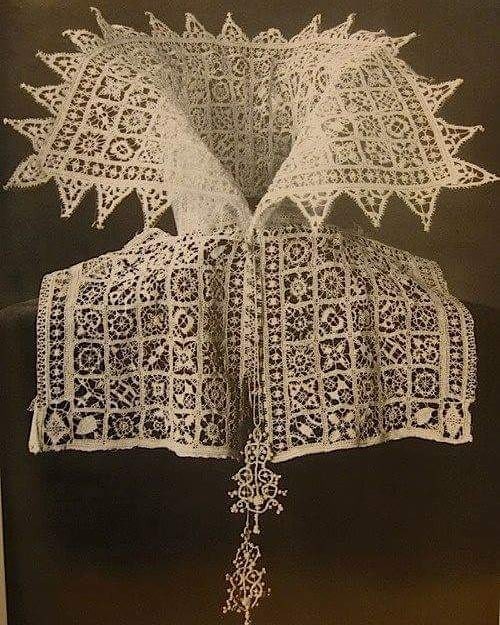

Unlike, say, the equally complicated and enchanting Jacobean needlework of the era, which was primarily made by men in guilds, lace craftsmanship seems to have flourished in high and low echelons of society, in common domestic spheres and royal couture alike; “Lace was also made at home, for the decoration of household linen, clothing and other objects,” explain the specialists at the Victoria and Albert Museum. They’d cover your dress, your chalice – even your coffin. The richer you were, the more extravagant the pieces became. Cuffs and collars of lace could say as much about your wealth as diamond necklaces and gold rings.

England’s King Charles I, ever the fashionista, demanded 1,600 yards of the stuff for his shirts. Lacework could be used as financial leverage, smuggled across borders, and symbolic of political and marital unions. The lace industry was so hot, that there were actually a government sanctioned lace maker holiday in November, called “Cattern’s day”.

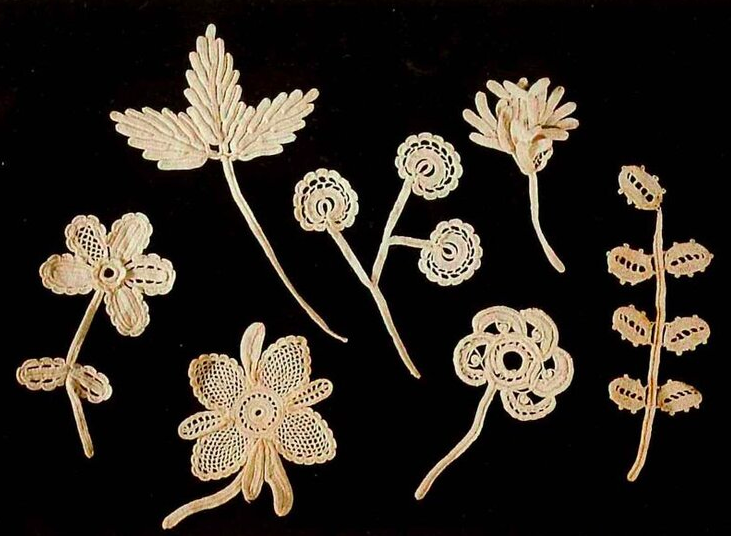

First, we have to admit that we didn’t really know exactly how to define lace. Recognise it? Sure. Explain it? Nope. According to the National Museum of American History, it’s an “ornamental openwork fabric created by looping, twisting, braiding or knotting threads either by hand or by machine.” Lace wasn’t so much a fabric, as it was a technique – if it’s a string, you can pretty much make it lace. Its main categories, when we’re talking handmade lace, are “needle lace, bobbin lace and decorated nets.” Each one requires deft hands for such minuscule knotting, twisting, netting and more…

The base of all lacework was – drumroll – netting! Its origins go back thousands of years, and very word “Lace” comes from the Latin root for ensnare, laceum. It wasn’t until the 16th century, says the the National Museum of American History, that lace artistry blew up in Europe with real extravagance and then spread to America.

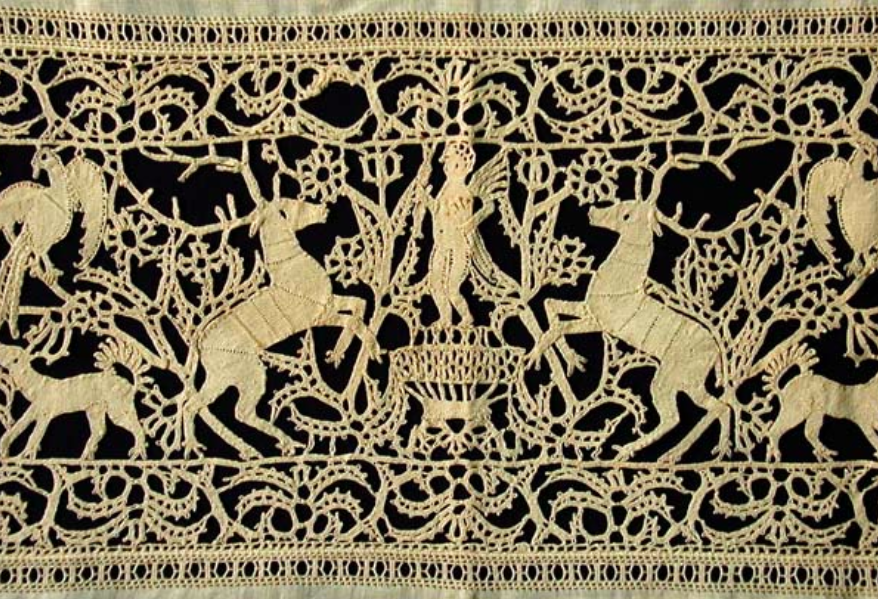

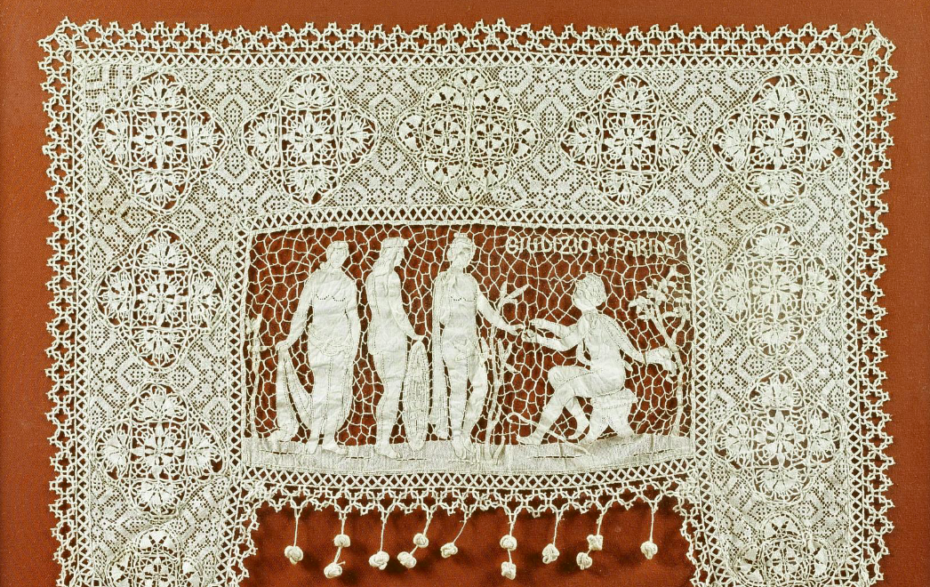

Threads of silk and precious metals were imported from the East, and lace making competitions and guilds were established. It transcended the space of domestic hobby, and became a way to flaunt your status; churches would commission “panel” pieces akin to antique comic books that played out biblical scenes, and it wasn’t uncommon to find lace embellishments on the coffins and chariots – as well as the cuffs – of aristocrats.

Lace, lace, and more lace was the mood for Queen Victoria’s 1840 wedding, from her invitations to the stunning dress itself. Just as Katie Middleton’s royal wedding gown launched a thousand copy-cat homages, Victoria’s frock kick-started another wave of the race for lace…

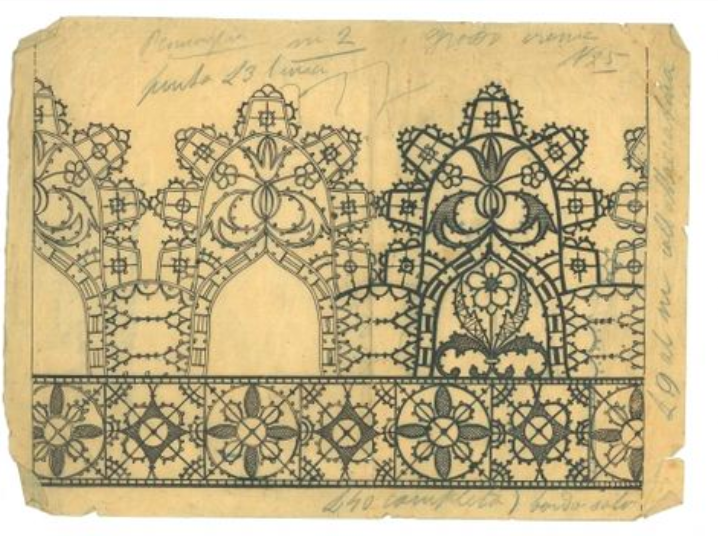

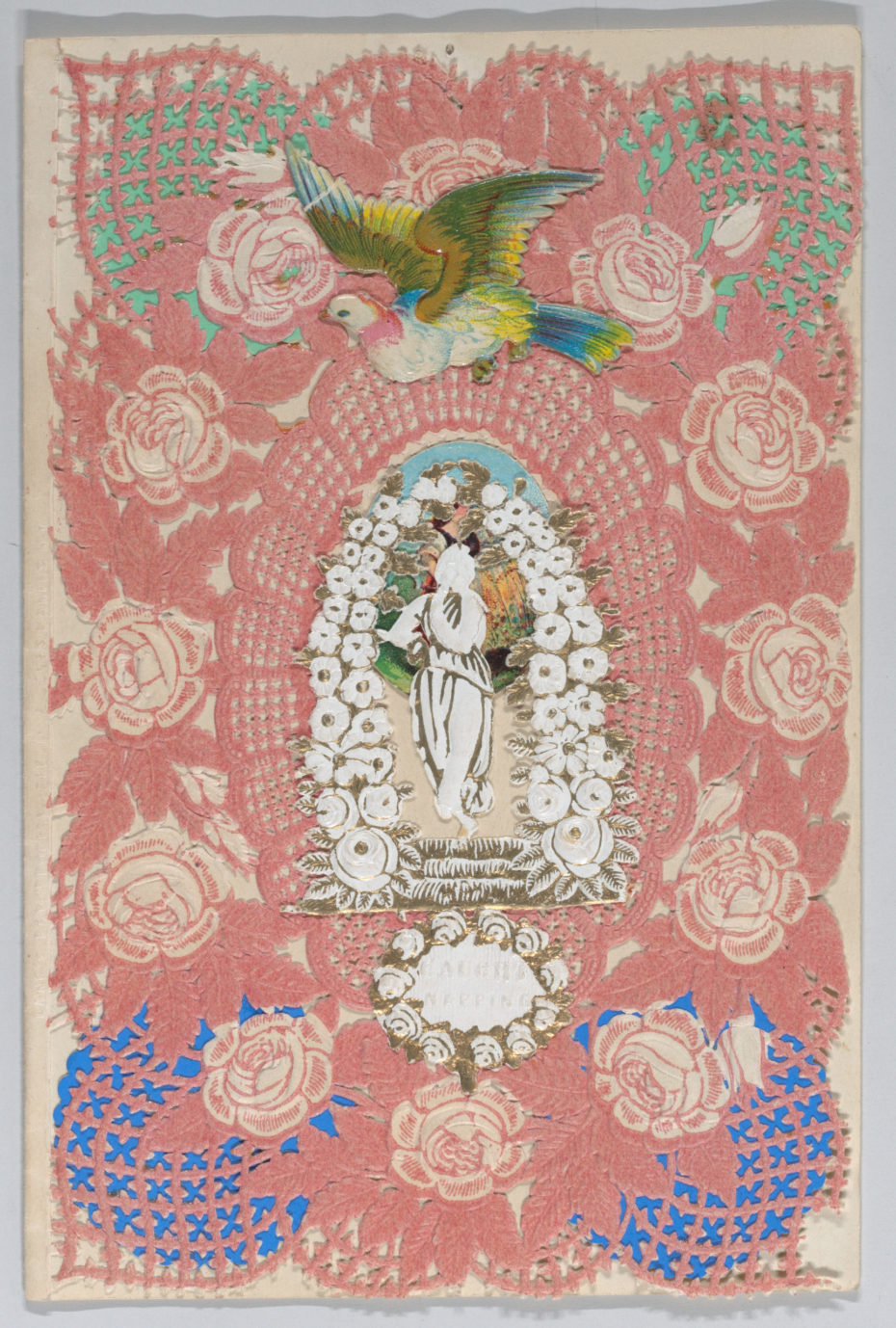

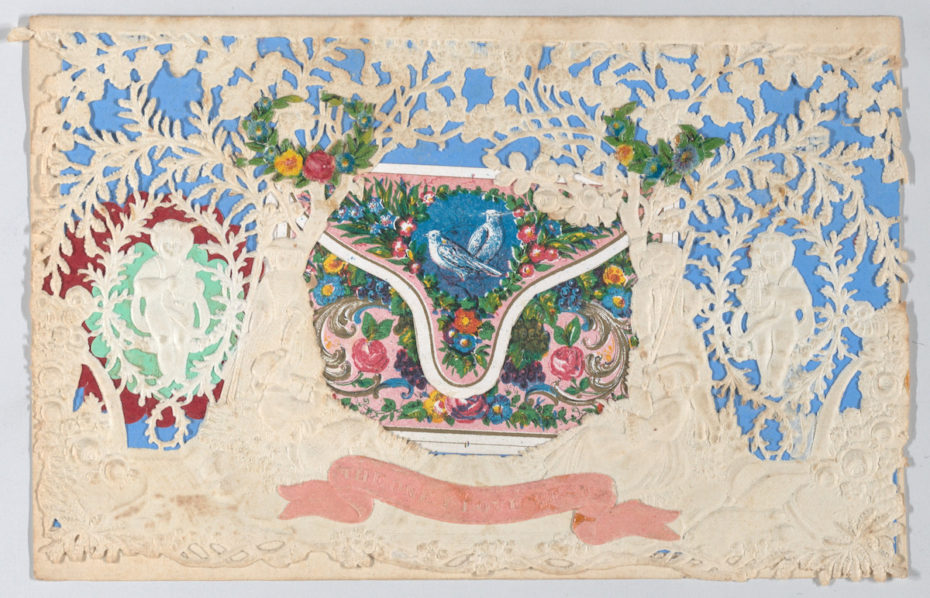

By the mid-19th century, cheaper and quicker means of production were under way. Paper cutouts of traditional lace designs, known as “open-work lace paper” became popular, and cotton thread – instead of gold and silk – was the order of the day.

On the one hand, lace purists may poo-poo the decline of an industry once dedicated to unique, handmade artistry. Totally understandable. On the other hand, not everyone can afford golden thread. The Industrial Revolution helped the romance of lace become a more accessible, and colourful place – consider the influx of 19th century, “paper lace” Valentine’s card cutouts:

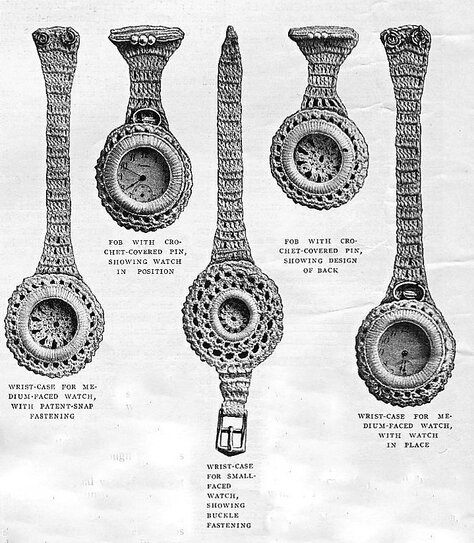

Men’s lace fashions went out of style by the 1800s and the trade of handcrafted lace took a nose dive from the industrial revolution, Thus, the art of lace making lived on in the domaine of women’s crafts – and as such, became inextricably bound to the way they tell their stories.

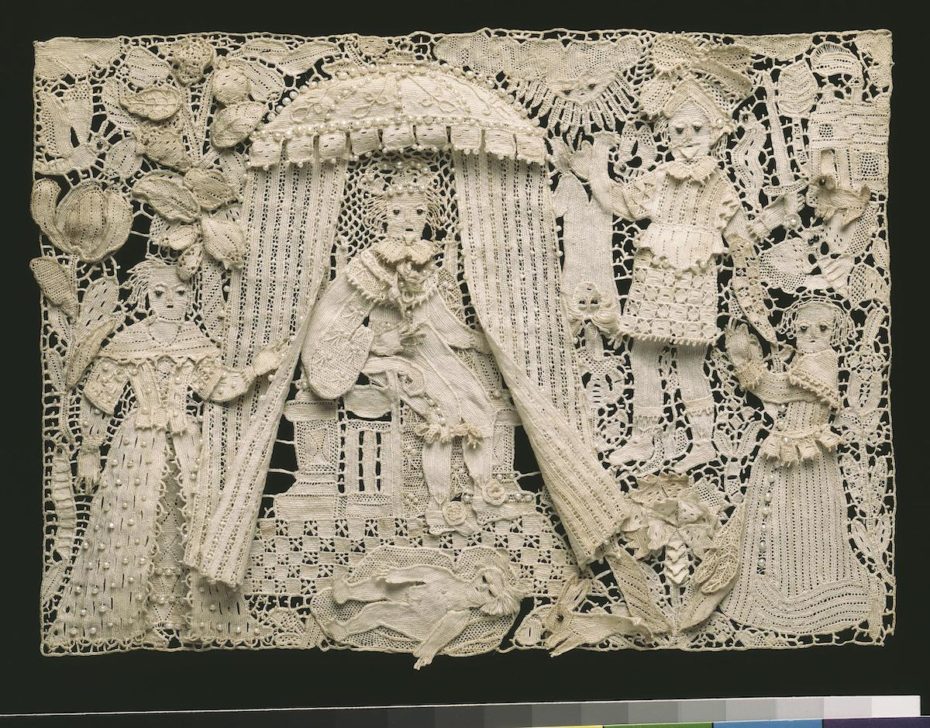

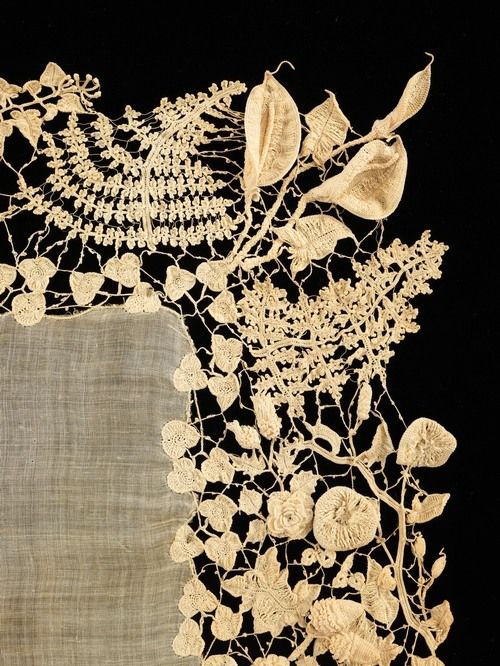

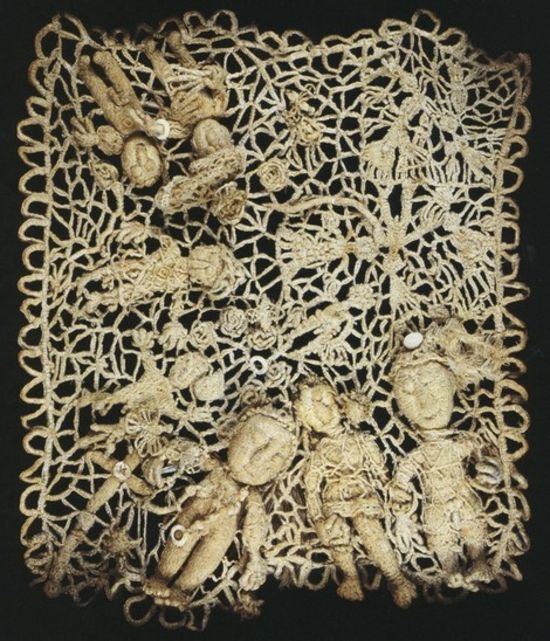

Consider the accidental, “autobiographical lace” made by Adelaide Hall. As a patient in a mental asylum in Washington, she used fabric as an expression of her world in the piece below, dated c. 1916. It’s a dazzling work, whose technical skill manages to feel both practiced and spontaneous:

The spirit of such craftsmanship lives on in the work of contemporary artists, like Lieve Jerger. Born in Flanders, Belgium – one of the hotspots of lace making in the 17th century – Lieve learned the craft from her grandmother, and since roughly the 1970s has been making allegorical, copper lace pieces on her grandmother’s oak bobbins:

So here’s to a future of art laced with stories, as it were, from across generations. And here’s hoping that the next time we stumble across a bit of lace or a forgotten bobbin, we take a moment to appreciate the breadth of this artistry’s joy. After all, you never know where it will turn up these days…

Learn more about Lieve Jergen’s work on her website.