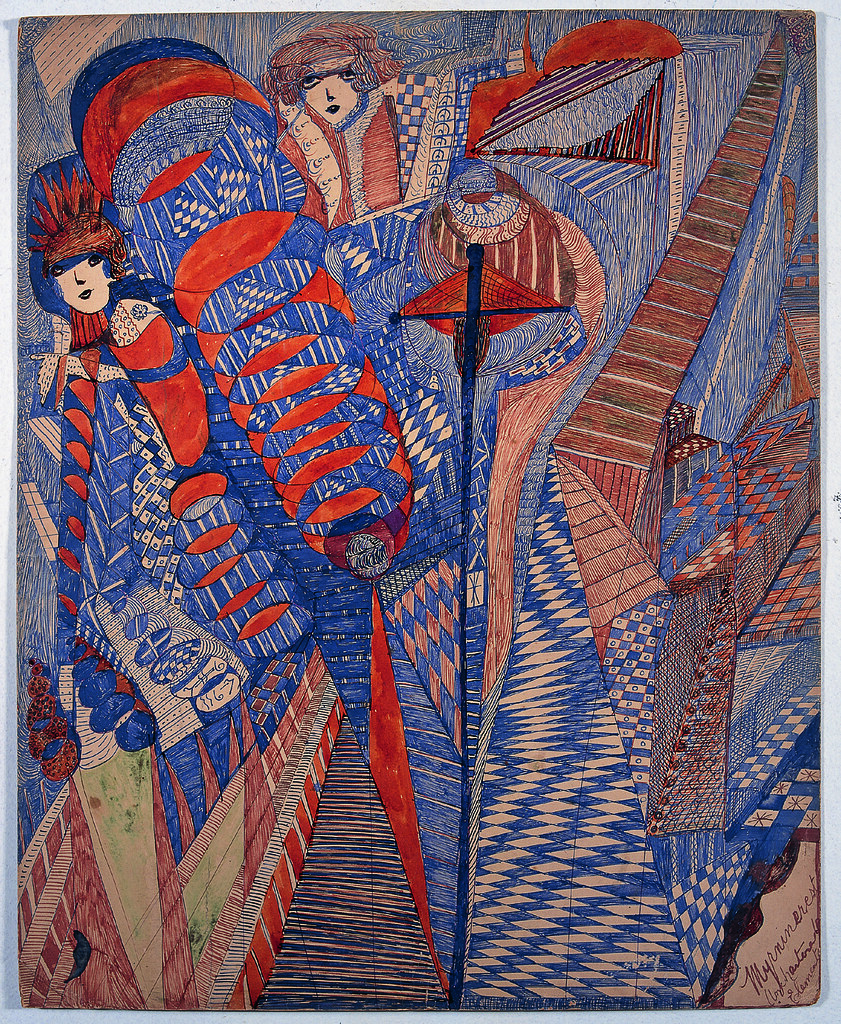

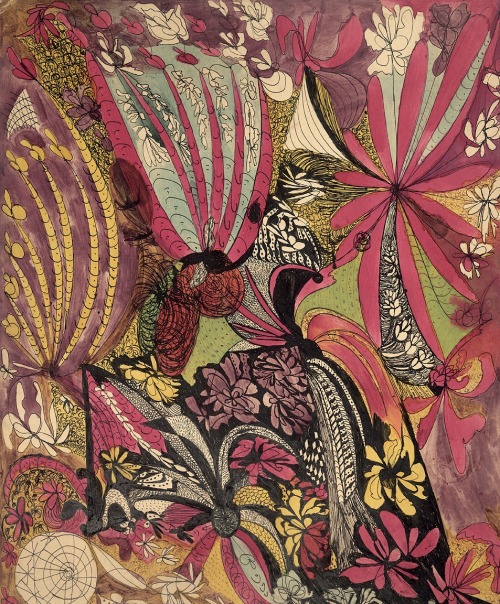

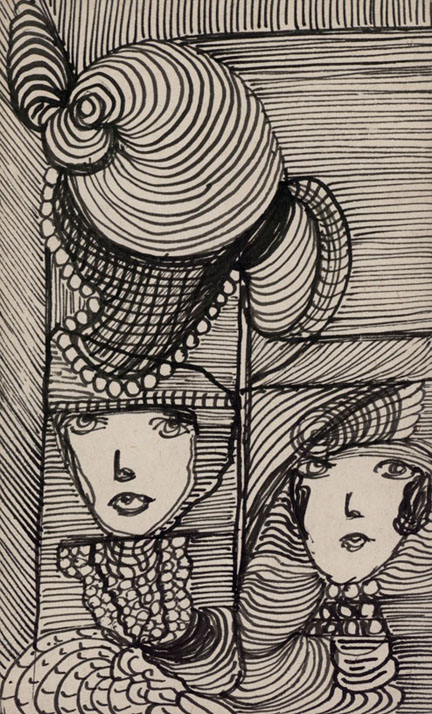

“Mediumistic Art.” It’s something we’d never heard of, until we uncovered the mysterious world of Mrs. Madge Gill. One of history’s most important outsider artists, Madge tended to her garden, her husband, and her children in what appeared to be the quiet life of a London housewife. But one day, she felt a stirring to create, and in the darkest hours of the night, she began to draw – and she wasn’t alone. Madge declared her artistic partnership with an otherworldly companion, a spirit called “Myrninerest,” as the guiding, ghostly of creative bouts. Together, they made an elaborate tapestry of thousands of works, from embroidered pieces to tapestries, gothic, architectural drawings to a kind of alphabet. Hsitory has labeled her art as “obsessive”and “giddy”; “ghostlike,” and existing in familiar, kaleidoscopic spaces. What really went on in the mind – and the heart – of Madge? Who was this Myrninerest? To untangle the truth about this fascinating artist, we have to turn back the clock…

The best introduction to Madge is found, in our opinion, is a head-first plunge into her art; into its mysticism, its intimacy – and dare we say, its touch of the divinely macabre, and oversketched works of Edward Gorey?

Even at a glance, the viewer can tell that this is a woman with a lot to get off her chest. For one, she born a fighter because she was born out of wedlock. Madge spent her childhood in orphanages that were cold at best, and entrenched in child labour practices at worst. Initially, she lived at “Dr. Barnardo’s Orphanage” in Barkingside, but was promptly shipped off to one of Britain’s experimental labour orphanages in Canada. There, she learned to work, and work hard. To have stamina, even at a cruel expense.

But she was determined to make it back to London. So Madge saved up her measly earnings, and came back – this time, as a triumphant young woman with a nursing career. She lived with her aunt for a while. She got married. She had children. She had, by all intents, the rest of her life’s legacy laid out neatly before her in the walls of her little East Ham home.

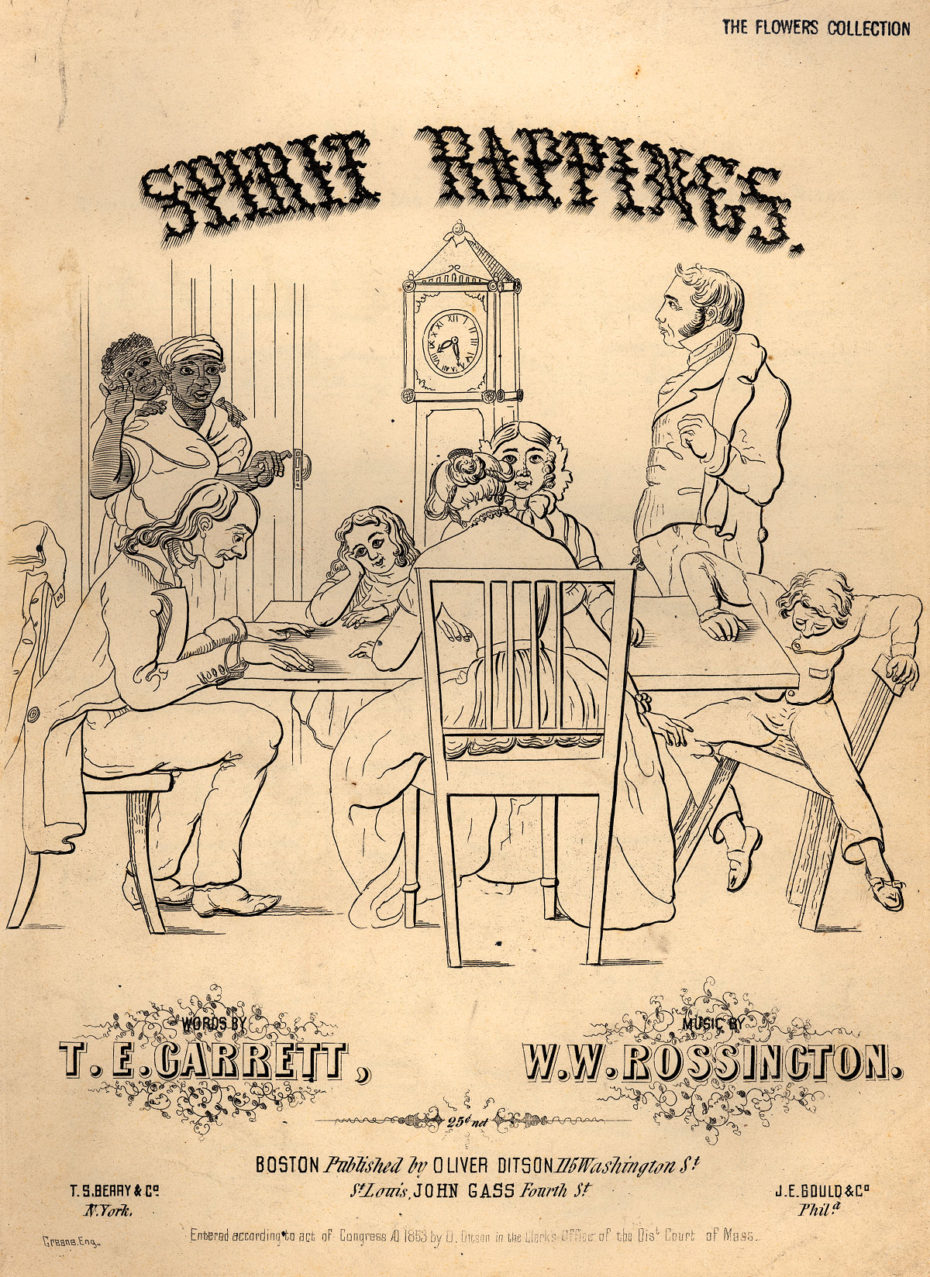

Still, Madge had other tastes. Otherwordly tastes. It was her aunt, in fact, you first led her down the rabbit hole of the esoteric; astrology and Spiritualism were both trendy pursuits at the time, and quickly became a lifelong passion of Madge. Which is how we arrive at Myrninerest, the being from “the other side” who Madge declared her “spirit guide.” Ostensibly ‘out-there,’ this was common practice amongst the trendy Spiritualists, who wouldn’t have batted an eye.

A word or three about the Spiritualists: these folks were exciting. They were finding a way of marrying Christian requisites with paranormal cravings, and began with the Fox sisters in the Unites States in 1848. Story goes, the ladies heard a mysterious knocking one day, only to discover that it was the attempt of a ghost to contact them. Though the Fox sisters “gifts” eventually revealed the episode as a hoax, the ensuing Spiritualist movement stuck, and spread, across all social classes; mainly because it touted a philosophy of an immaterial, “other” reality unveiled through pseudo-scientific practices, all backdropped by the comfort of the existence of the afterlife. It had its skeptics, most famously Harry Houdini. Yet, even today, New York’s Village of Psychics thrives.

This is why it’s so important contextualise Madge’s “Mediumistic” art, lest we fall into the toxic trap of seeing her ‘partnership’ with Myrninerest as out of left field, or worse, “hysterical.” At the same time, there were dark elements of Madge’s life that had been swept under the rug, elements that inevitably coloured the themes of her art.

It’s said that her marriage went sour quick. After all, it had likely been a union of convenience; her husband, Tom Gill, was the son of the aunt she lived with upon her return to London. True tragedy came with the death of their second child, Reggie, from the Spanish Flu, and that of their subsequent stillborn daughter. Madge was heartbroken. She herself almost died giving birth, and was bedridden for months. When she was released from the hospital, she’d lost all sight in one eye. It was then, in the throes of darkness, that she started to draw.

25 x 20 in. ©Christie’s

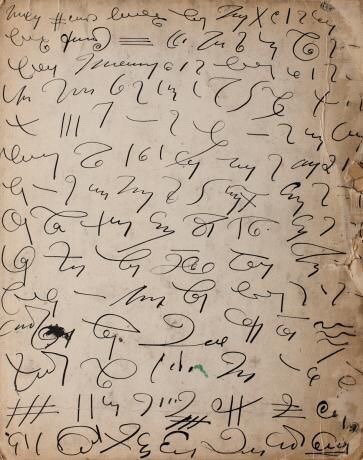

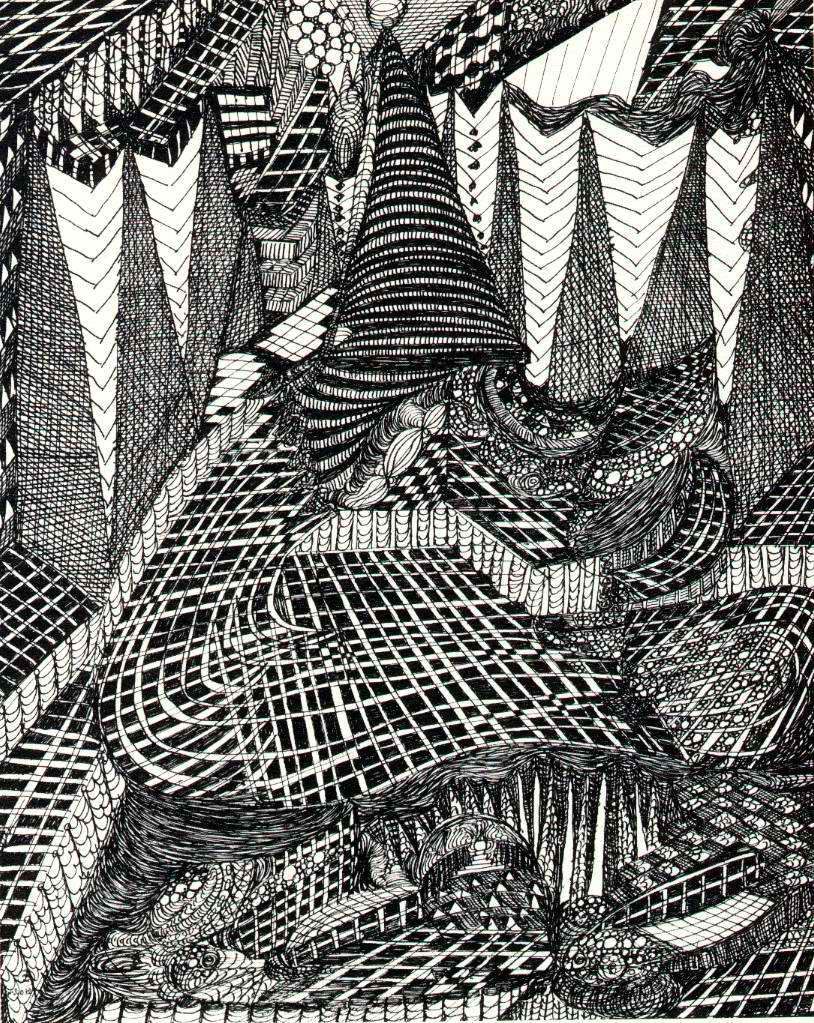

She’d create dozens, even hundreds of works in a single night. Works of “esoteric knitting.” Works as small as a postcard, or as a part of a 30-metre-long calico roll piece:

Untrained and unstoppable, Madge basically kicked off an artistic career at 38-years-old…

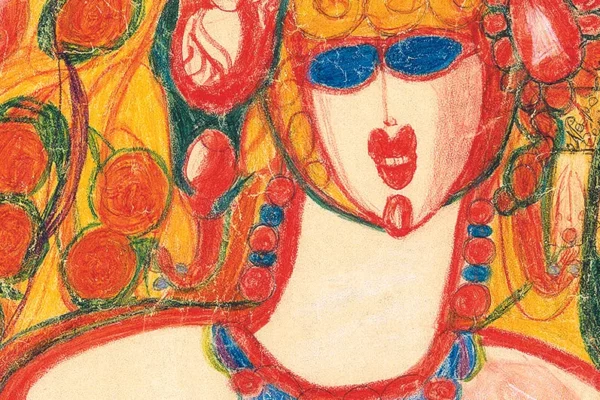

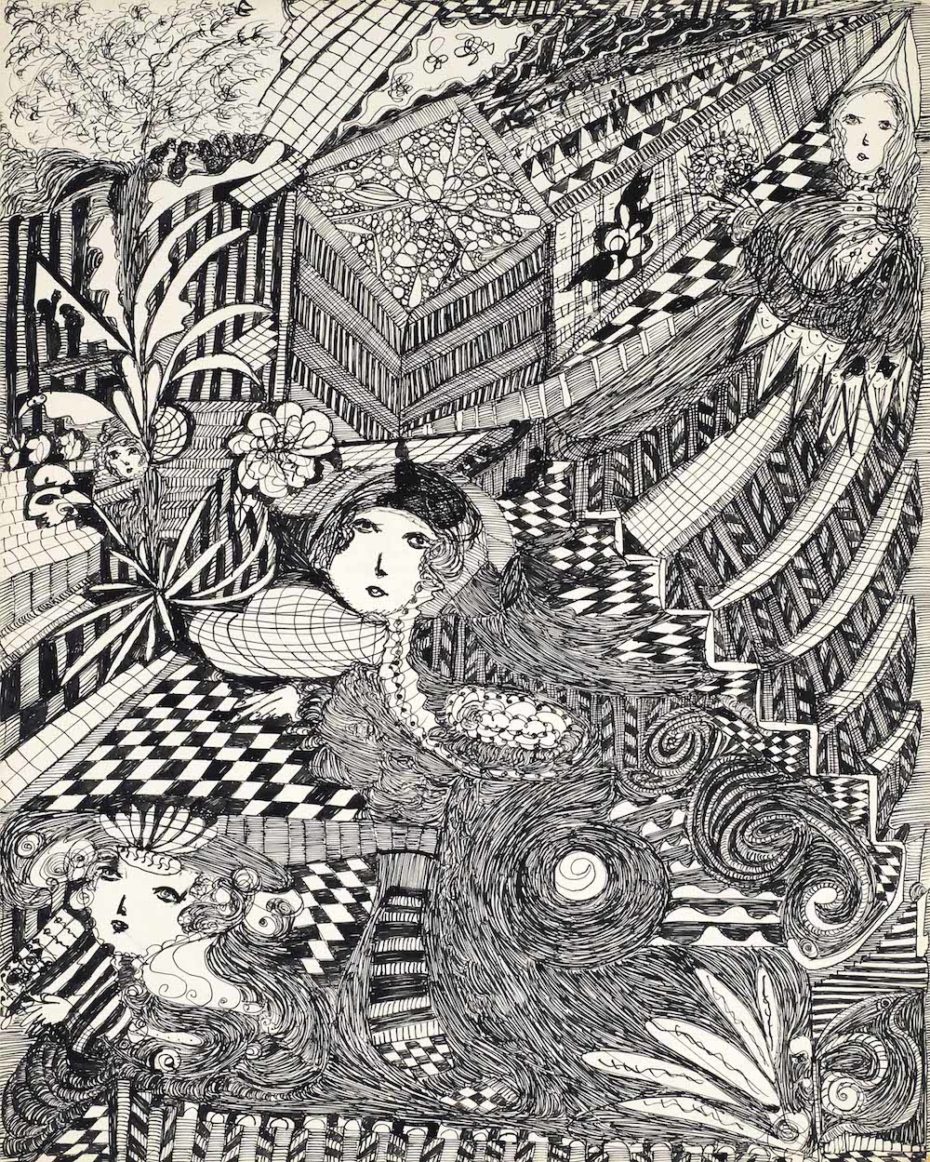

The works were always crowded with ambiguous forms and shapes, save for the very distinct face of a woman. Or several women? It was possible that she was drawing her spirit guide, as Madge did say it was Myrninerest who made her draw in the first place. Maybe she was drawing herself, or her darling daughter. Perhaps, in a way, she was putting pen to something ineffable to which so many women – so many people – can relate.

“Always the same woman’s face,” reflects author Agnes Cardinal in Quests in a Cupboard, “in Madge Gill’s created world, the artist appears time and time again as a heroine, spectator and creator.” Today, most critics agree with Cardinal, applauding Madge’s work within the context of art brut as a uniquely “refracted and ongoing autobiographical project.”

There was pain in Madge’s work, but there was also an assertion of newfound individuality. She had an exhibit at Whitechapel in her lifetime, although she purposefully priced the work astronomically high so that it wouldn’t sell – lest, she said, it make Myrninerest angry. In that way, she’s quite unlike her reclusive contemporaries, Henry Darger and Adolf Wolfili. Madge was a quasi-closeted artist – one does not, after all, unfurl 30 metres of paper unnoticed.

When Madge died in 1961, hundreds of additional works were rescued from a slow, forgotten decay in her house and moved into her borough’s Heritage and Archive Service. She’s slowly been earning more and more of the respect she deserves over the years in the art world, as well as in her community. As of 2018, a blue plaque hangs a 71 High Street, Walthamstow, London in celebration of her life.