Its recipe has taken thousands of years to perfect, and if we follow the forgotten trail, its secret history can lead us from the ancient tombs of antiquity to underground societies that paved the way for freedom of expression. Contrary to popular assumption, lipstick was in fact genderless for most of its existence, and as we shift into the dawn of a renaissance for female emancipation and gender fluidity, the house of Gucci is rewriting the rules of beauty once again with this underestimated cosmetic tool as a symbol of strength and identity.

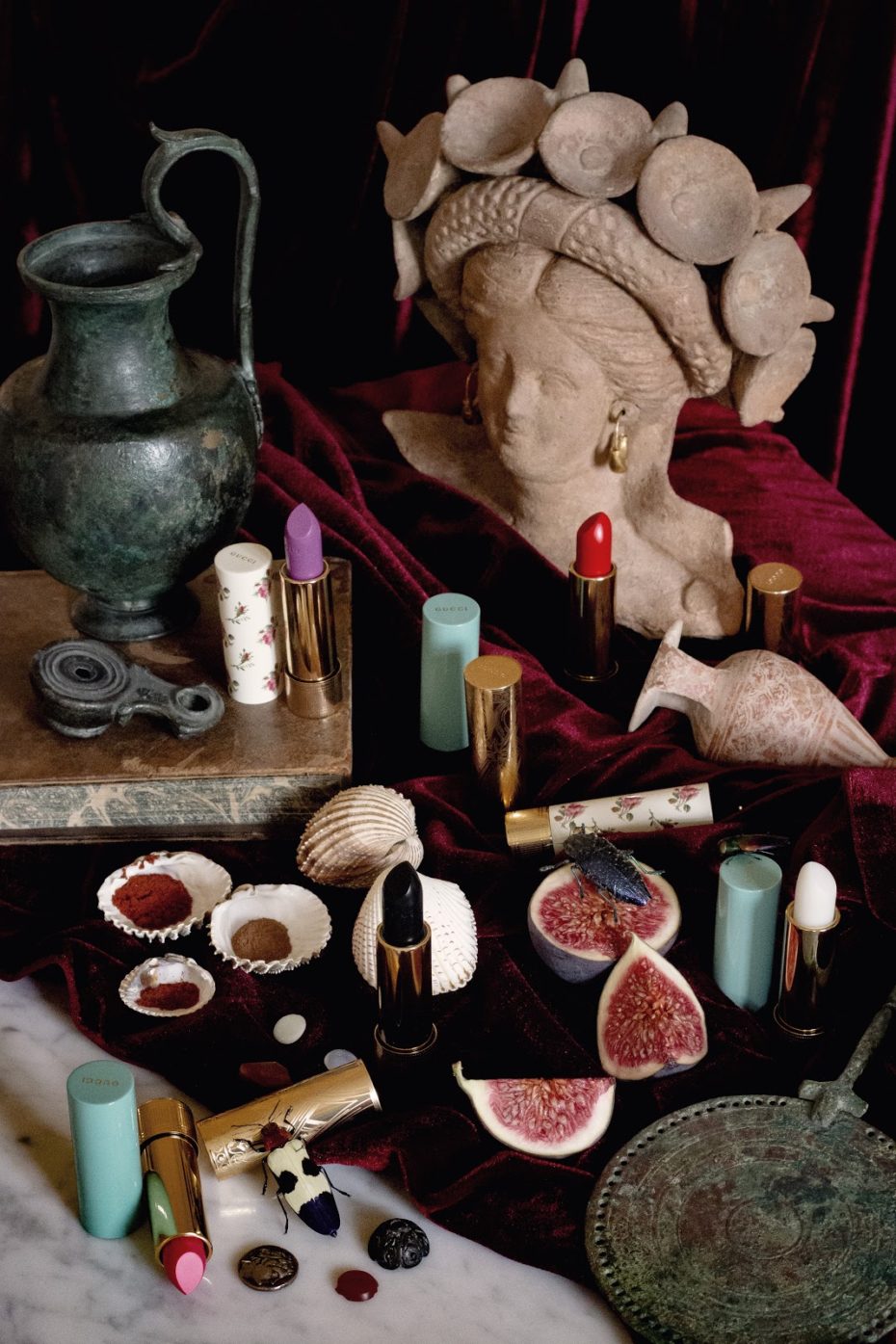

The story begins 5,000 years ago, on the dressing table of a Sumerian queen in the city of Ur in modern-day Iraq. Most of Queen Puabi’s narrative has been lost in the wrinkles of time, but her legacy has been attached to the first recorded use of lip rouge in history. A highly respected figure in one of the earliest known civilizations in Mesopotamia, she wore elaborate head pieces and jewellery, but a key part of her look was her brightly coloured lips, which she painted using a powder concoction made from red rocks and white lead and contained in cockle shells. The trend spread amongst her people and to neighbouring civilizations, like the Minoans, who used a purplish-red pigment produced from a gland in the murex shellfish.

Skip forward some 2,000 years and it was none other than Cleopatra that took the baton and pioneered make-up amongst the ancient Egyptians, for both men and women. Heavily-painted black eyes weren’t complete without boldly painted lips in shades of orange, magenta and blue-black. Ancient Egypt’s avant-garde also used the same dye as a blush, applying red ochre to their cheeks, not just for aesthetic purposes, but also to protect their faces from the harsh conditions of the desert. They too, carried pots of lip paints and cosmetics into burial tombs with them for the afterlife, believing their key ingredient, the scarab beetle, was a symbol of immortality. Thousands of years later, tombs would be excavated and discovered in these regions with cockleshells and pots containing lip paint beside their ancient remains.

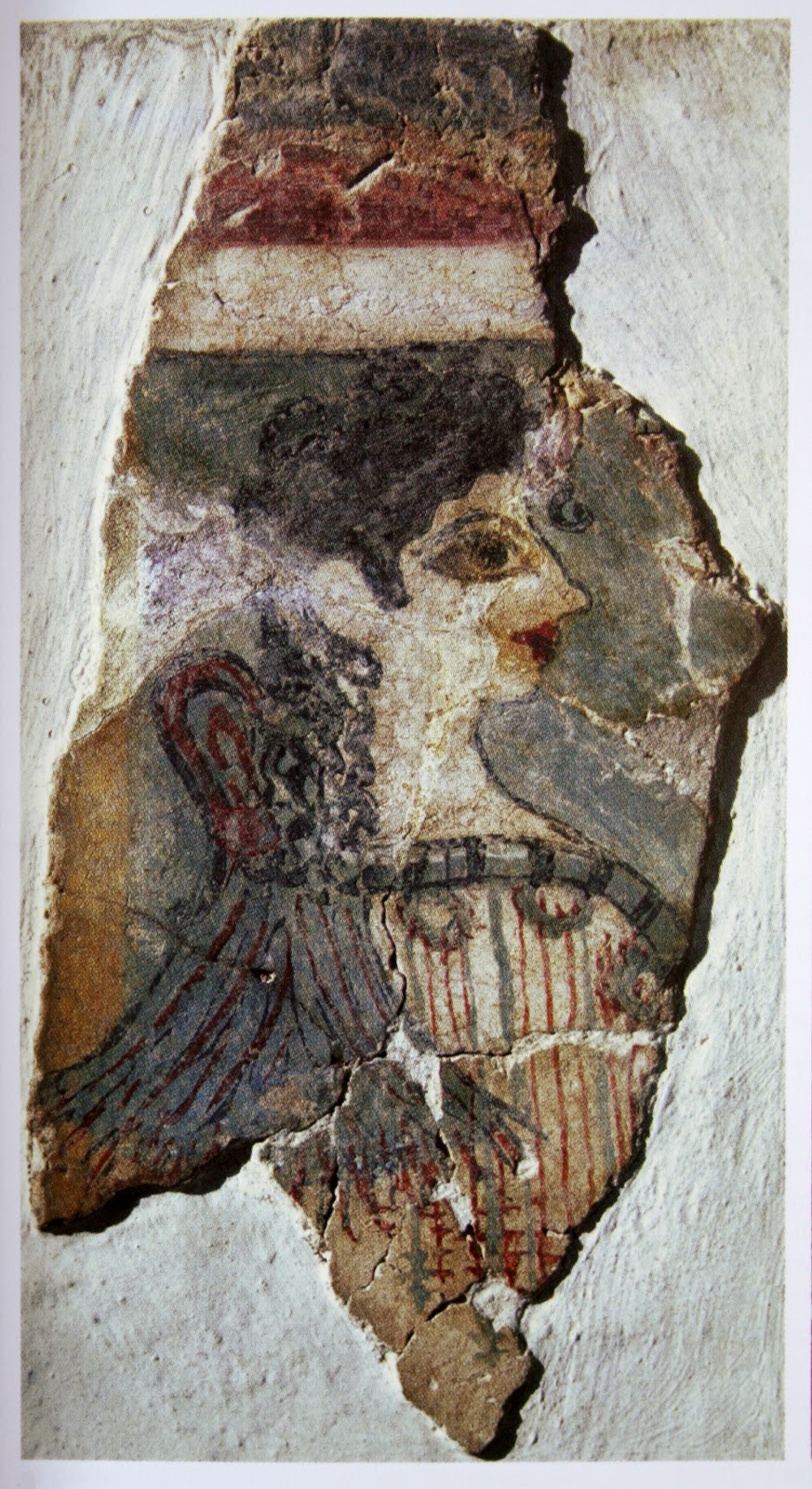

In antiquity, it was the Middle East that certainly had a more liberal attitude towards lipstick, as evidenced by wall paintings that show women with brightly coloured lips. The ancient Greeks had a more complicated relationship with lip paint however, where it became increasingly entangled with societal status. Predominantly worn by sex workers of the period, it became a sort of symbol of the profession, signifying their status, to the point where if ever one of these women would be out in public at the wrong time of day, or without their designated lip paint, they could be chastised and punished for posing as “respectable ladies”. Alongside red dye and wine residue, they improvised with a surprising range ingredients including sheep sweat, human saliva and even crocodile excrement.

Under the Roman Empire, lip paint became genderless once again, but was still used to denote social rankings, particularly amongst high ranking male officials. Women of the upper echelons also experimented with lip make-up; the eccentric Empress Poppaea Sabina, wife of the notorious Emperor Nero, is said to have had the ultimate glam-squad of 100 attendants, ready to make sure that her lips were freshly painted at all times. Mulberries, lemon, rose petals and wine residue were among the popular ancient homemade ingredients for lip rouge. Meanwhile, back over in the Middle East, around 9 AD, an Arab scientist, Abulcasis accidentally invented the solid lipstick while making a stock for applying perfume which could then be pressed into a mold. He tried the same method with colours and invented solid lipstick. Such a novel substances earned lipstick a slightly superstitious and wicked allure.

As the Dark Ages cast its shadow over Western Europe however, religion clashed with cosmetics and churchmen wrote about lipstick as a form of sacrilege. While men of the barbarian invasions painted their faces and lips blue as they went into battle, women who wore make-up were deemed to be incarnations of Satan himself, and pressured to repent for their “sinful” use of lip rouge to priests during confession.

During the Crusades of the Middle Ages, when Europe began rediscovering the Middle East and its superstitious beliefs surrounding cosmetics, intrigued, the wealthy and worldly elite would have alchemists create their lip rouge and apply it while doing incantations. Black market peddlers began selling their own “exotic” and mystic mixtures in medieval Europe. Macabre became the beauty trend du jour of the Middle Ages. Women who were brave enough to disobey the church, used lip color to make their complexion look paler and ghostly by contrast, and would concoct their rosey lip rouge from mashed up red roots, rose petals and sheep fat.

In Venice, the most prosperous city in the West and far removed from the backwardness and poverty of medeival Europe, high society ladies wore bright pink lip rouge and the popular class wore an earthier red lip rouge. During the Renaissance period with its famous courtesans, women used lip rouge with abandon.

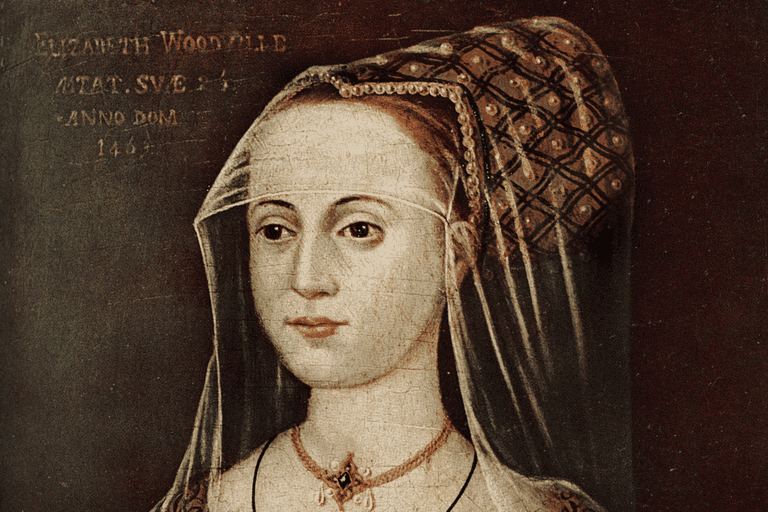

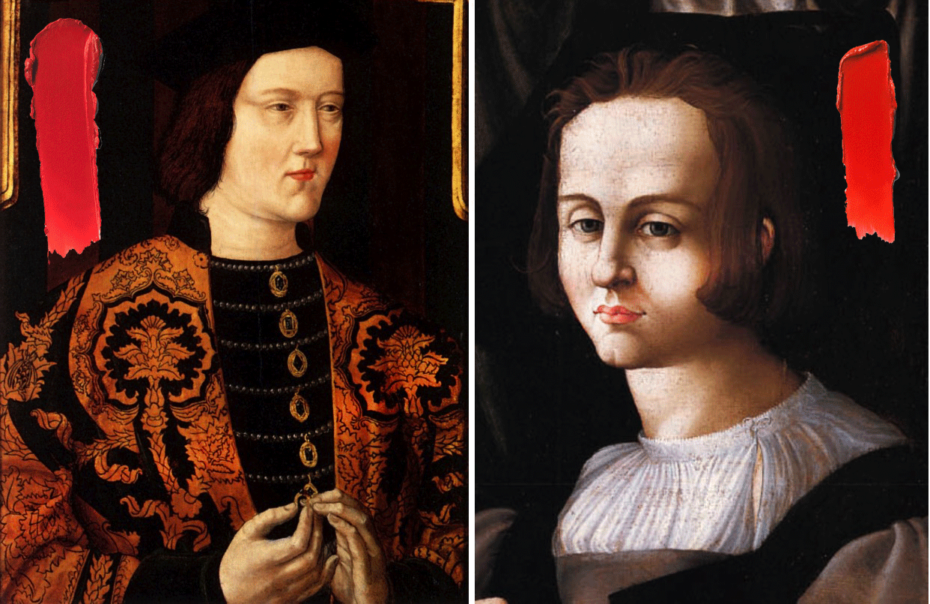

The cosmetics trend eventually made its way to England, where, both the women and men of Edward IV’s court wore lip rouge. Even the king himself christened a few official lip rouges, such as “Raw Flesh” and the more you look at late Medieval and Renaissance art with this in mind, the more you’ll notice men wearing lip rouge.

Finding its way up the social ladder again, lipstick made its way back into the embrace of high society royalty, while still holding onto the mysterious allure of its Dark Age superstitions. Queen Elizabeth I, a lip rouge devotee, had her own recipe for her own personalised shade, and is said to have invented the lip pencil with one of her close aids by mixing colours with plaster of Paris, rolling the paste into a pencil shape, and drying it out in the sun. The great English queen was such a devotee to lipstick that she believed it could ward off illness, and was reportedly wearing half a inch of lip rouge on her deathbed. This adulation of lipstick and its mysterious powers trickled down into mainstream English society, where it was even traded as a substitute for money in some cases.

Across the waters in France, both male and female courtiers openly wore bright red lips inspired by the makeup they’d see at the theatre. This metrosexual trend paved the way for the storied 18th century macaroni; well travelled British male aristocrats who dressed in an embellished androgynous style. They sported rouged lips and cheeks, pox patches, powdered wigs, lace cascading from their collars and sleeves, bejewelled fingers with painted and manicured nails. A Macaroni paid great attention to his appearance with tighter waistcoats, heeled shoes, and elaborate hairstyles that matched the towering hairstyles of the female coiffure. The “macaroni” look got its name from the rising excitement at the time around Italian pasta, which was a then-novel product brought to England by well-travelled men coming back from their Grand Tours; pretty much the gap years of their time. Meanwhile in the New World, American women emulating the European obsession came up with enterprising ways to achieve the rouged look – rubbing red snippets of ribbon across their mouths and carrying around lemons to suck on throughout the day.

But then Victorians came along and put a damper on things. In her mourning years, Queen Victoria imposed an empire-wide prohibition on lipstick, declaring that makeup was dishonest and impolite. Rebellious women of society began secretly trading make-up recipes and making homemade lipsticks in underground lip rouge societies and clandestine beauty establishments that ushered veiled devotees of lip rouge into private rooms where they could stock up on cosmetic ingredients and smuggle back home in secrecy.

We owe the mainstream re-introduction of lipstick to the burgeoning actresses at the turn of the century, who took their professional makeup looks from the stage to the streets. Actress Sarah Bernhardt caused great scandal in the 1880s when she applied red lip rouge in public. Lipstick, femininity and rebellion soon began to converge in tandem with the unfolding women’s rights movements.

With the endorsement of leading suffragettes, lipstick became somewhat of a symbol for female emancipation. Leaders such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Charlotte Perkins Gilman wore a particularly noticeable shade of red lipstick, and in both America and England, women publicly applied lip rouge with the express intent of appalling men.

Queue the Golden Age of Hollywood when “It girl” actresses like Clara Bow and Theda Bara prompted women worldwide to emulate their trademark Cupid lips. Hot studio lamps caused the actress’ lip pomade to run, so pioneering makeup artists of the day started using greasepaint foundation to cover their natural outlines of a leading lady’s mouth and then placed only thumbprints of lipstick at the centre of her lips. Clara Bow took a liking to the look and kept wearing the professional makeup outside of the studio and on magazine covers, prompting thousands of women around the world to emulate the silver screen star.

During wartime, the production of lipstick in Europe was held back due to rationing, but for Americans, lipstick became indispensable to the war effort, sold as a morale-boosting symbol of girl-power in the face of danger. Factory dressing rooms were stocked with lipstick and female marines had an official shade: “Montezuma Red”.

There are even examples of lipsticks that were creatively disguised as binoculars, and equipped with emergency flashlights in case of blackout. For the United States however, lipstick became indispensable to the war effort. It was sold as a symbol of resilient femininity in the face of danger, and came to boost morale.

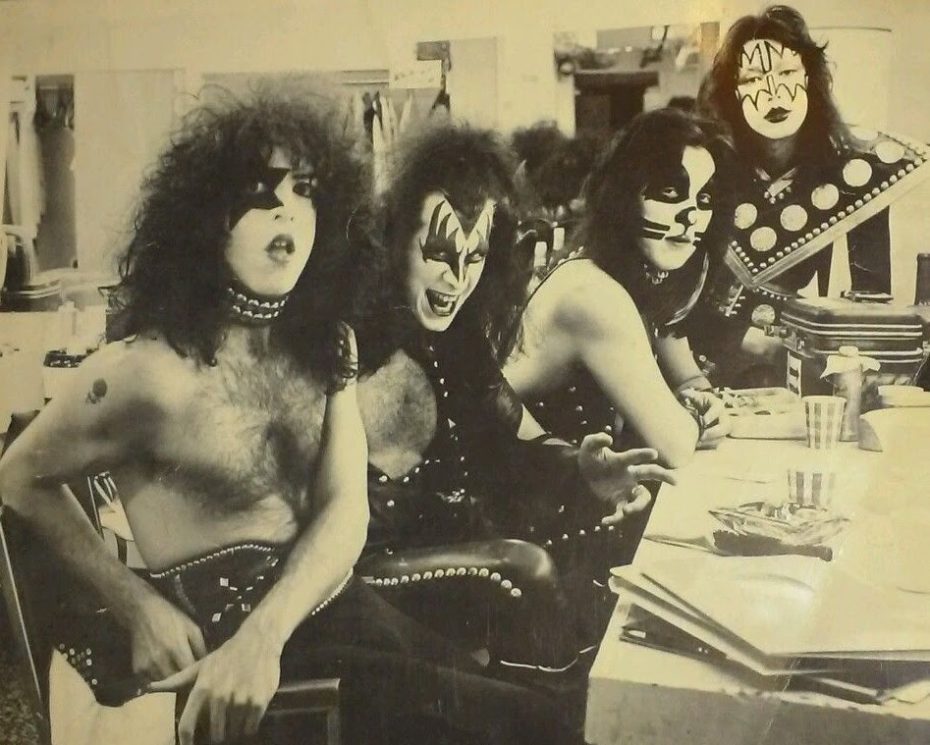

Come the 1970s and lipstick once again became a tool for social rebellion, adopted by both sexes of the punk-rock music to express nonconformity. Purple and black became the most popular colors of the day and re-opened the doorway to gender bending without sacrificing masculinity. Bowie and glam-rocker Lou Reed were both fans, Gary Glitter, Kiss, Alice Cooper, and Mick Jagger all led the way too.

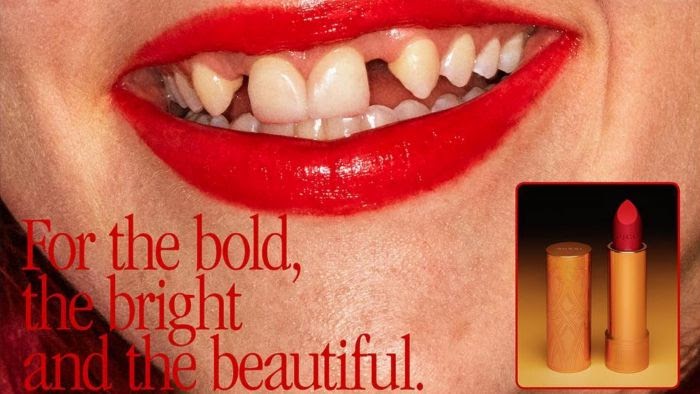

As we enter the 2020s, this iconic cosmetic tool is once again becoming a symbolic instrument of change, as we shift into a new era for female emancipation and gender fluidity. Gucci’s trailblazing lipstick campaign created by Alessandro Michele sends a strong and much-needed message: it’s time to break away from society’s image of perfection. It’s time to love our imperfections.