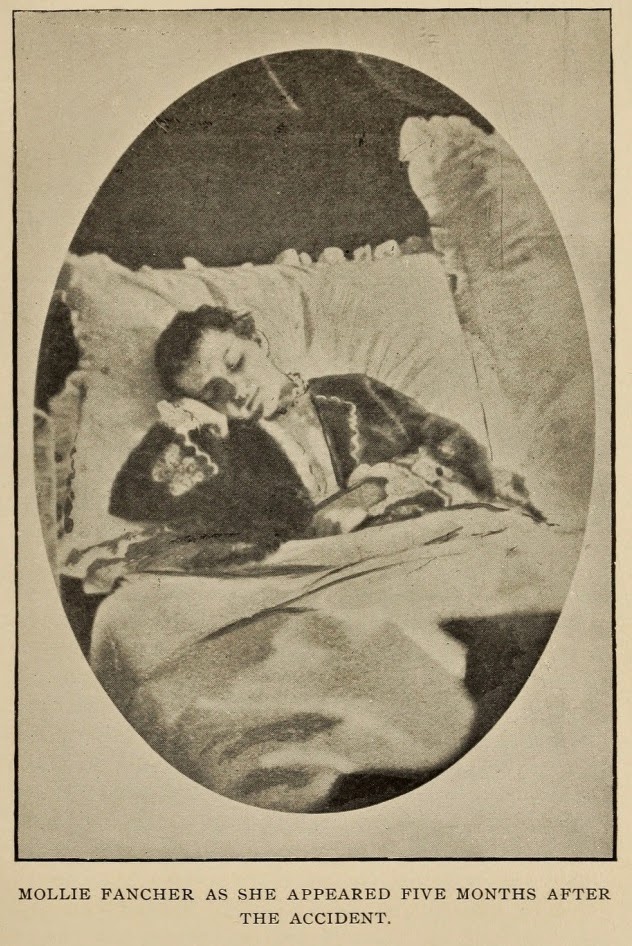

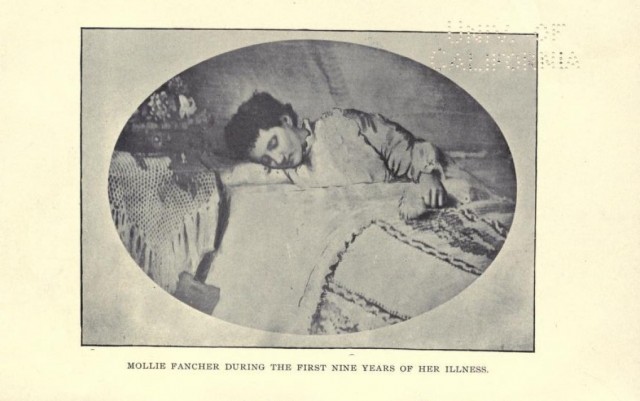

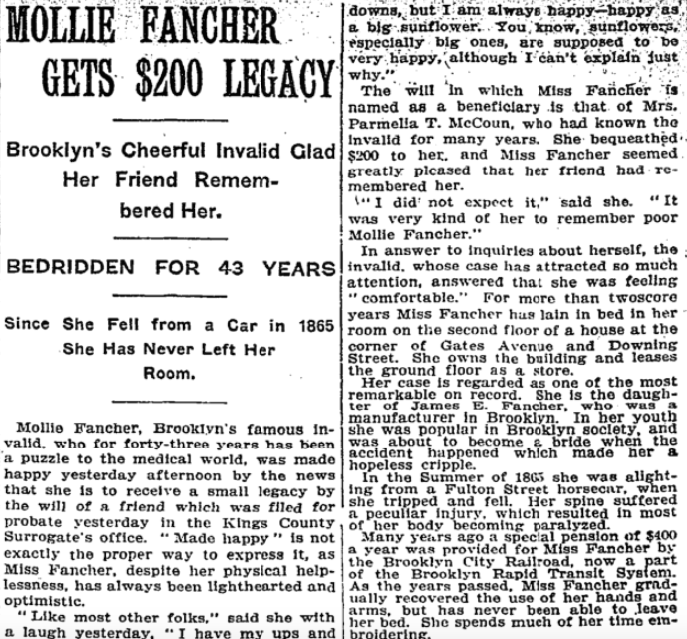

Mollie Fancher spent half a century in her bed. They called her “The Brooklyn Enigma,” but she was born your average, middle class New York gal. That all changed in 1865, when she gained fame from a freak accident in which she fell out of a horse-drawn trolley, and was dragged behind by her scarf. Miraculously, declared the papers, she survived – but her convalescence took a strange turn. Fancher claimed to have lost her sight, but gained a newfound connection with the spirit realm. She declared no need to eat or drink, able to survive over indefinitely long periods of time without nourishment. She stayed bed-ridden for the next 48-years. And she wasn’t alone. Fancher was just one of the many ghostly “Fasting Girls” of the Victorian era who fascinated the public, while something much darker, something yet unnamed, cried out for attention. Misunderstood and misdiagnosed, were Fasting Girls the undiagnosed Victorian victims of anorexia nervosa?

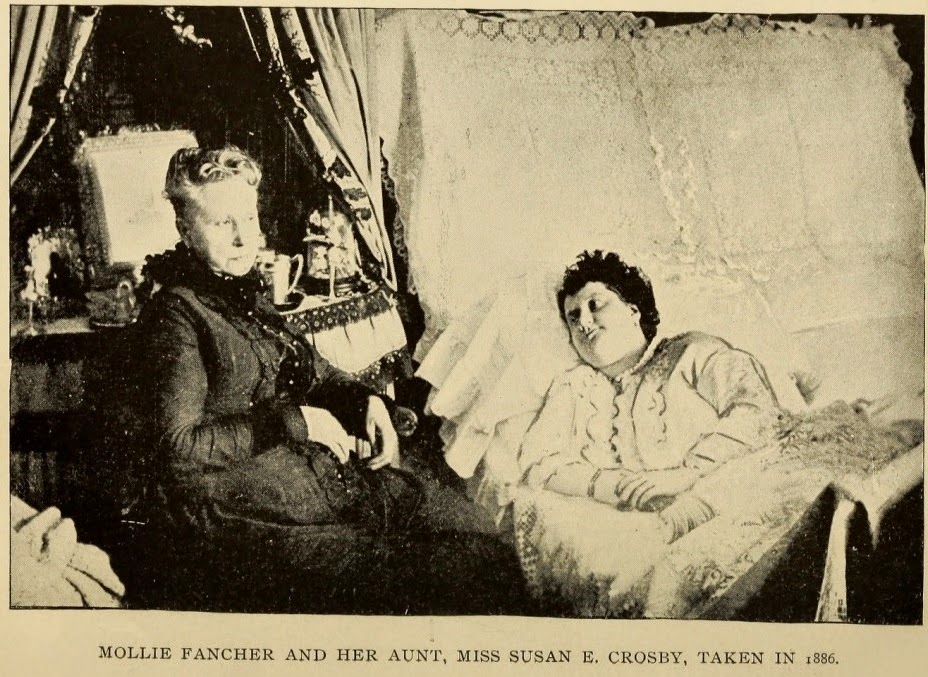

Fancher was described as a “tall, slender and graceful young lady, a decided blonde, and a universal favourite among her schoolmates” by Abram H. Dailey, in an 1894 report that compiled various testimonials about her life. She was also described as an excellent student, with real courage and ambition. In fact, the trolley incident came just two years after another near fatal horseback-riding accident. Meaning: Fancher was a go-getter. Which is what makes her seemingly passive, bed-ridden future so peculiar.

Fancher slowly recovered from basically being declared dead by her physician, and claimed to experience a series of trances. She had lost her sight, but, placing her hands behind her, claimed to see through the back of her head. “I am sometimes conscious of what others are not,” she said, and explains how she stopped eating. “I rejected it. My doctor thought I was insane, but, as a matter of fact, I had never been more rational in my life.”

She claimed she could read, even without use of her eyes, and predict the future; she created beautiful tapestries despite the fact that her hands were paralysed. You can actually find one of her creations on display at a hotel in Lily Dale, New York’s “Village of Psychics”, a blossoming Spiritualist community during the time of Mollie Fancher’s notoriety. But more on that in a moment…

When Fancher died in 1916, it was with her mysterious legacy in tact. No one had tested her, which is more than one can say for the other Fasting Girls of the era. Consider Sarah Jacobs, “The Welsh Fasting Girl,” who claimed to have stopped eating at the age of 10. The vicar called her a miracle child, but skeptical doctors decided to put her to the test at a nearby hospital.

Under the constant surveillance of nurses, Jacobs began to starve. When her parents refused to let the nurses give her nourishment – they’d seen her in this state before, they claimed – she died. Sarah’s parents were convicted of manslaughter. If you should happen to be in New York City, you might consider popping into Green-Wood Cemetery you’ll find Mollie Fancher’s gravestone with the inscription describing a woman who “knew the secret of life” who spent “half a century in her bed”.

Then there was Lenora Eaton, a respectable New Jersey girl whose claims of miraculously living without food were put to a fatal test in 1881 – a little over a month after investigators arrived at her home to survey her case, she died. Then, in 1889, Fasting Girl Josephine Marie Bedard from Tingwick, Quebec, was also revealed as a fraud with one humiliating Boston Globe headline: “Who Took the Cold Potato? Dr. Mary Walker Says the Fasting Girl Bit a Doughnut.” As public interest in the women grew, the Nickelodeon and Stone and Shaw’s Museum tried to figure out ways to make the Fasting Girls part of their playbill.

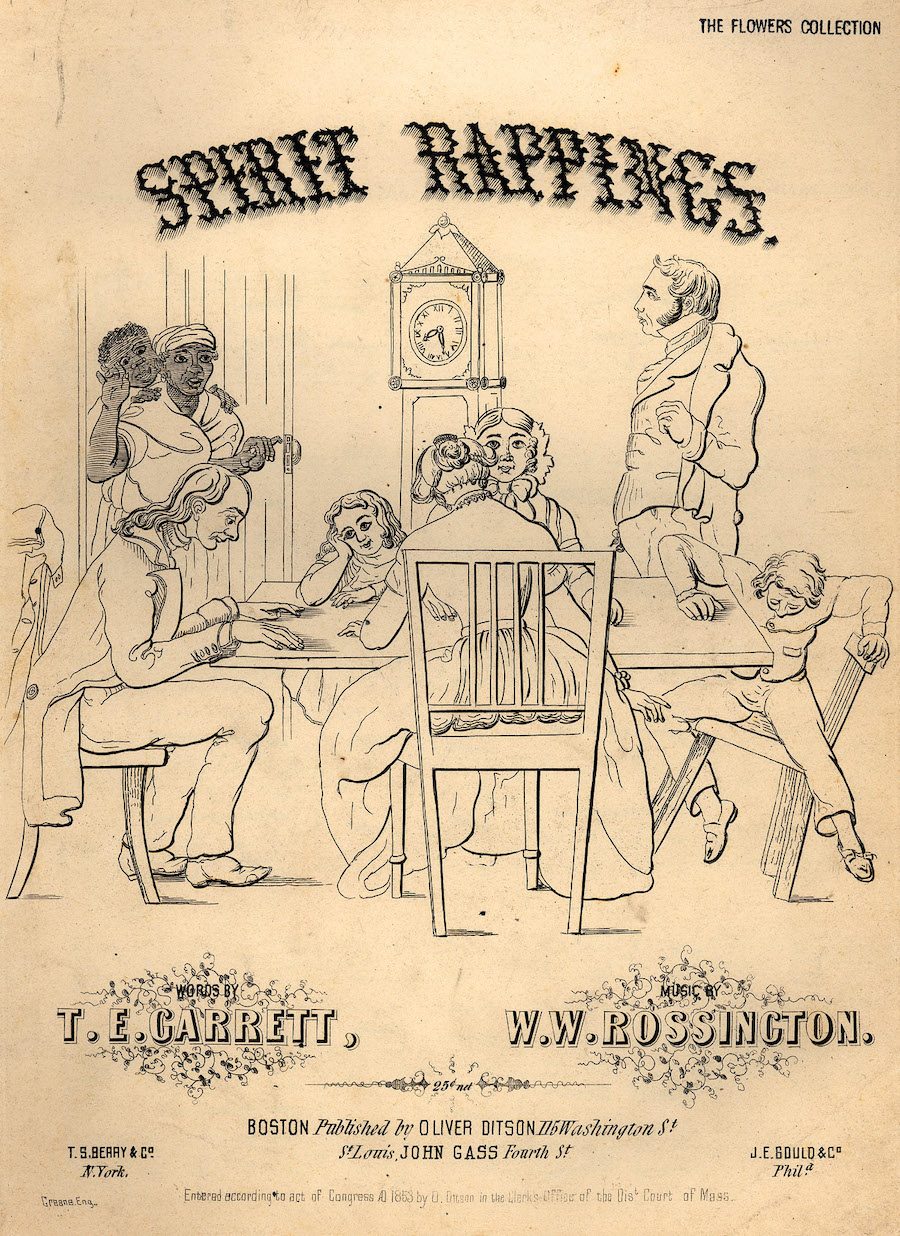

The interesting thing about Fancher and these other cases, was how naturally they leaned into their esoteric connotations. The Spiritualist Movement was thriving in America and abroad, and Fancher’s self-proclaimed ability to connect with the heavens was right on trend.

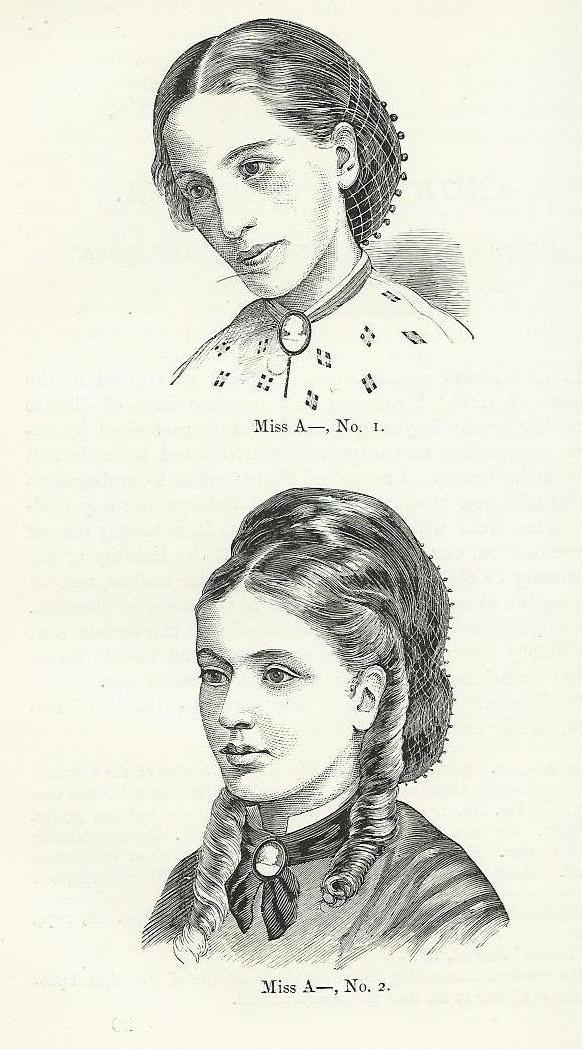

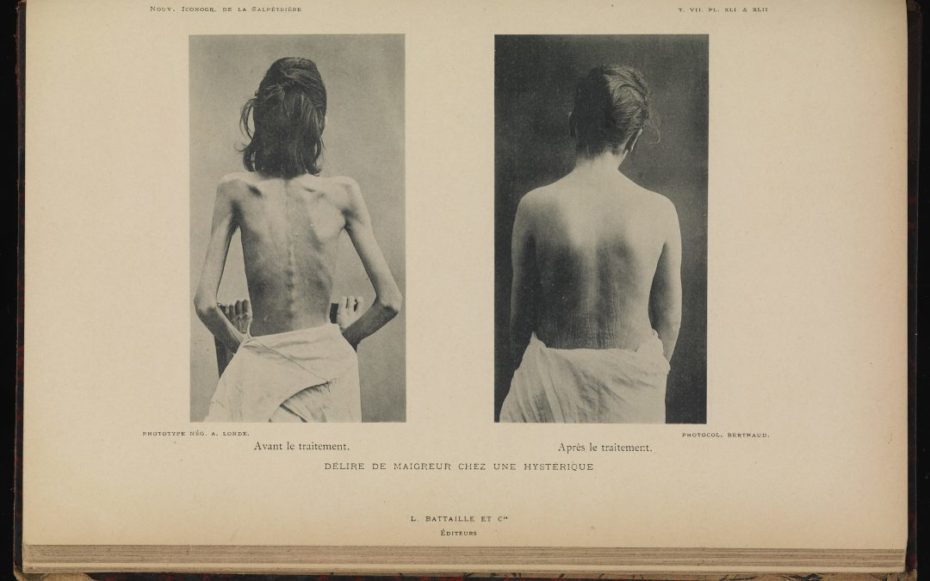

Was it for money? Fame? The Fasting Girls did receive gifts from the public, but they came from pretty well-off, middle to upper-class families and didn’t really need money. As readers in 2020, we naturally connect the dots to eating disorders like anorexia nervosa – which was barely understood at the time. It was only identified in 1873 by one of Queen Victoria’s personal physicians, Sir William Withey Gull. The same year, a French physician published a paper on other cases, De l’Anorexie hystérique, but it wasn’t until the latter half of the 20th century that the disease started gaining widespread awareness.

In a conference at Cornell in 2012, sociologist and author of The Fasting Girls, Joan Jacobs Brumberg, explores how the cases of these women reveal a pretty wild power play at work. Anorexia nervosa, she explains, has always depended on a big tangle of factors: biological vulnerability, psychological predisposition, as well as the environment at home and in the culture at large. This was no different in 1870-something, a time when the culture at large saw this extreme female fasting as equal parts shocking, and alluring.

Lest we should forget, this was an era in which the ideal Western woman was trying to become a living porcelain doll; she unknowingly poisoned her eyes with drops of belladonna to make them appear big and glossy. She had a fainting couch. She knew it was trendy to look pallid, as if she had a touch of “Consumption” (Tuburculosis). In 1881, The New York Times described Mollie Fancher with eerie wonder: “She lay on a low bed in dainty white clothing […] her skin was wonderfully fair and smooth…” She was basically the first Manic Pixie Dream Girl.

Joan Jacobs Brumberg thinks some of these Fasting Girls, especially Fancher, had a subversive motive. Note that in Fancher’s writing, she underlines her clarity of mind – her reason – in coming to the decision to fast. “Food and eating were loaded with negative meanings,” says Brumberg, “especially for girls of the middle and upper classes […] food symbolised sexuality and lack of self restraint. Control of the body and its processes were important to Victorian women.” Some didn’t even admit defecation or urination, saying it happened “but a few times a week.” Many were vegetarians “because meat was a ‘hot’ food associated with carnality.” Thus, upper-class Victorian girls who decided to consume food – or a lack-thereof – on their own terms, were taking radical and obsessive control of their lives, even if the messages they were sending felt mixed.

Unfortunately, not only did these cases almost always end in tragedy, but they didn’t elicit a progressive response from the public. Consider Queen Victoria’s physician who coined the term anorexia nervosa; he wrote off the Fasting Girls as an example of the usual “morbid perversity of the adolescent girl.” Which is why voices like Brumberg are so important; hers is of many researchers that are opening up a progressive dialogue on the disease in the 20th century. Because, yes, it really has taken that long: it wasn’t until 1978, when psychiatrist Hilde Bruch’s The Golden Cage: the Enigma of Anorexia Nervosa was released, that a wider public conversation truly started on the disease.

Eating disorders have been around since, well, forever. In antiquity, descriptions of religious fasting dating from the Hellenistic era and self-starvation by women in the name of religious piety and purity was a fairly common medieval practice. Catherine of Siena and Mary, Queen of Scots were both believed to have suffered from the condition. Is it a coincidence that Queen Victoria’s physician was the first person to finally name the disease? With their rigid corsets, porcelain doll aspirations, and obsession with death, mourning and looking macabre, might the Victorians might have been dealing with a serious eating disorder epidemic? Just another thing our history books may have overlooked.