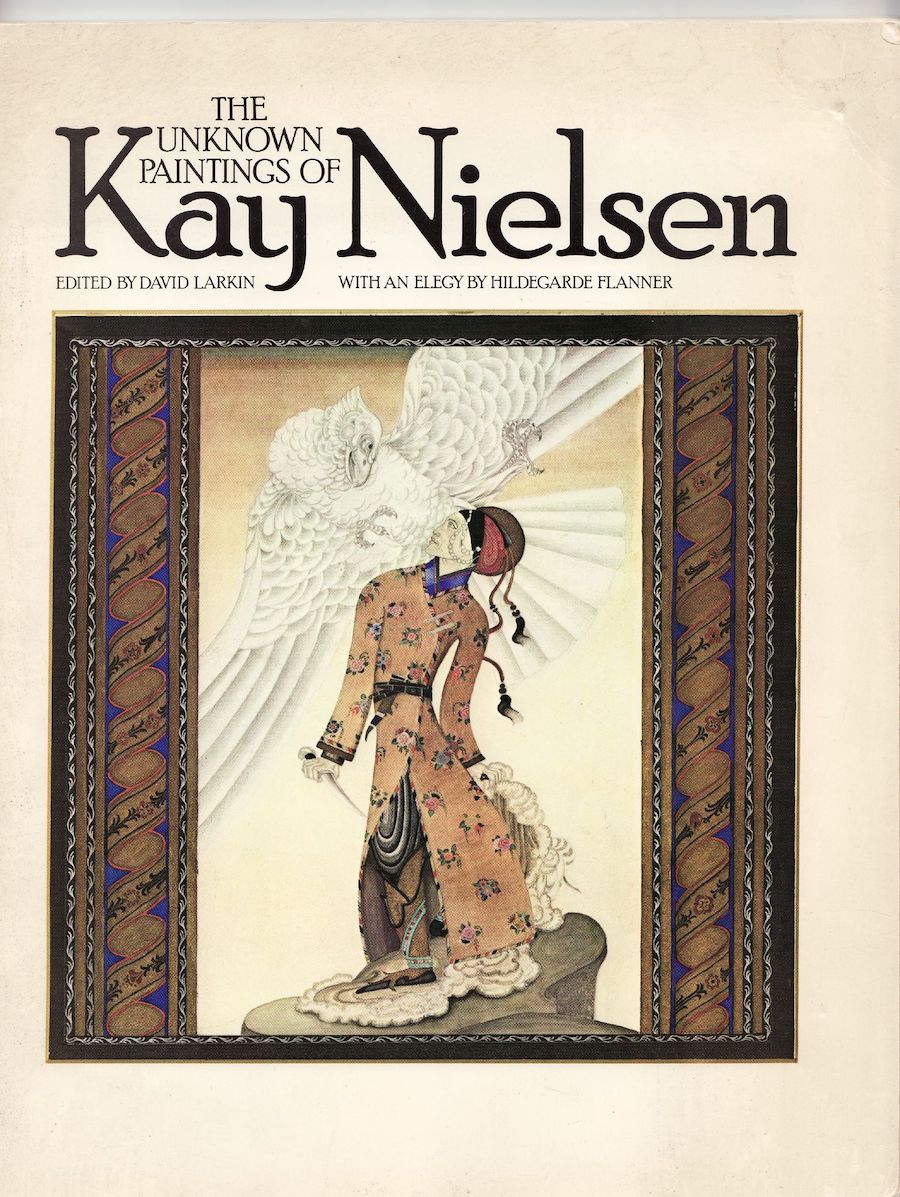

Kay Nielsen knew his way around a fantasy. The Danish illustrator was raised in a “tense atmosphere of art” (his words) during the Golden Era of Illustration – a time when folks one-upped each another with books bearing golden spines and marbled end papers; elaborately illustrated copies of Grimm’s Fairytales, The Wizard of Oz, and Oscar Wilde’s witticisms. Nielsen was the cream of the crop, and remembered not only for his sublime contributions to storybook volumes, but his work on the iconic animated Disney film, Fantasia (1940) – in fact, he was kind of a Disney darling until the company abruptly let him go. One look at his work, and it’s clear: he’s their One Who Got Away…

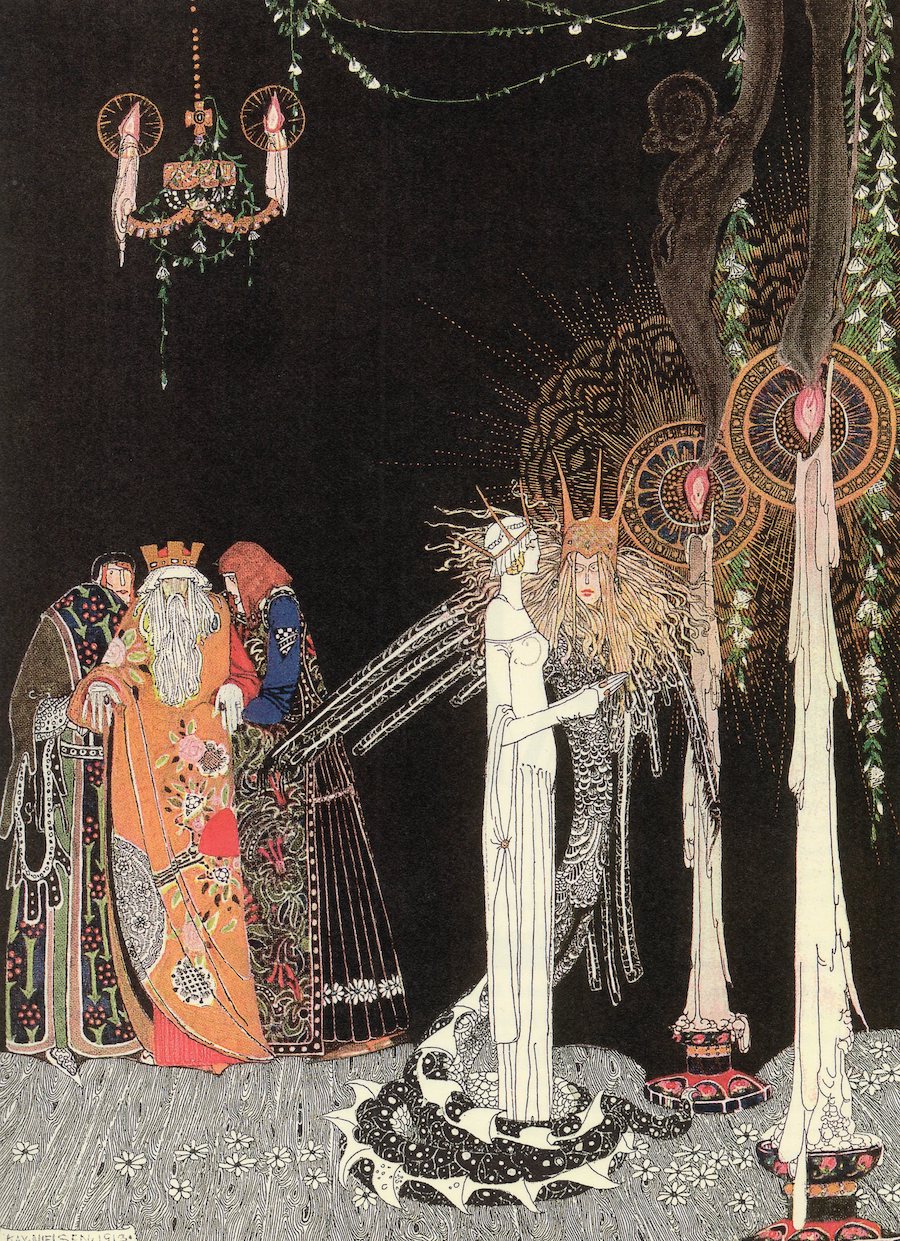

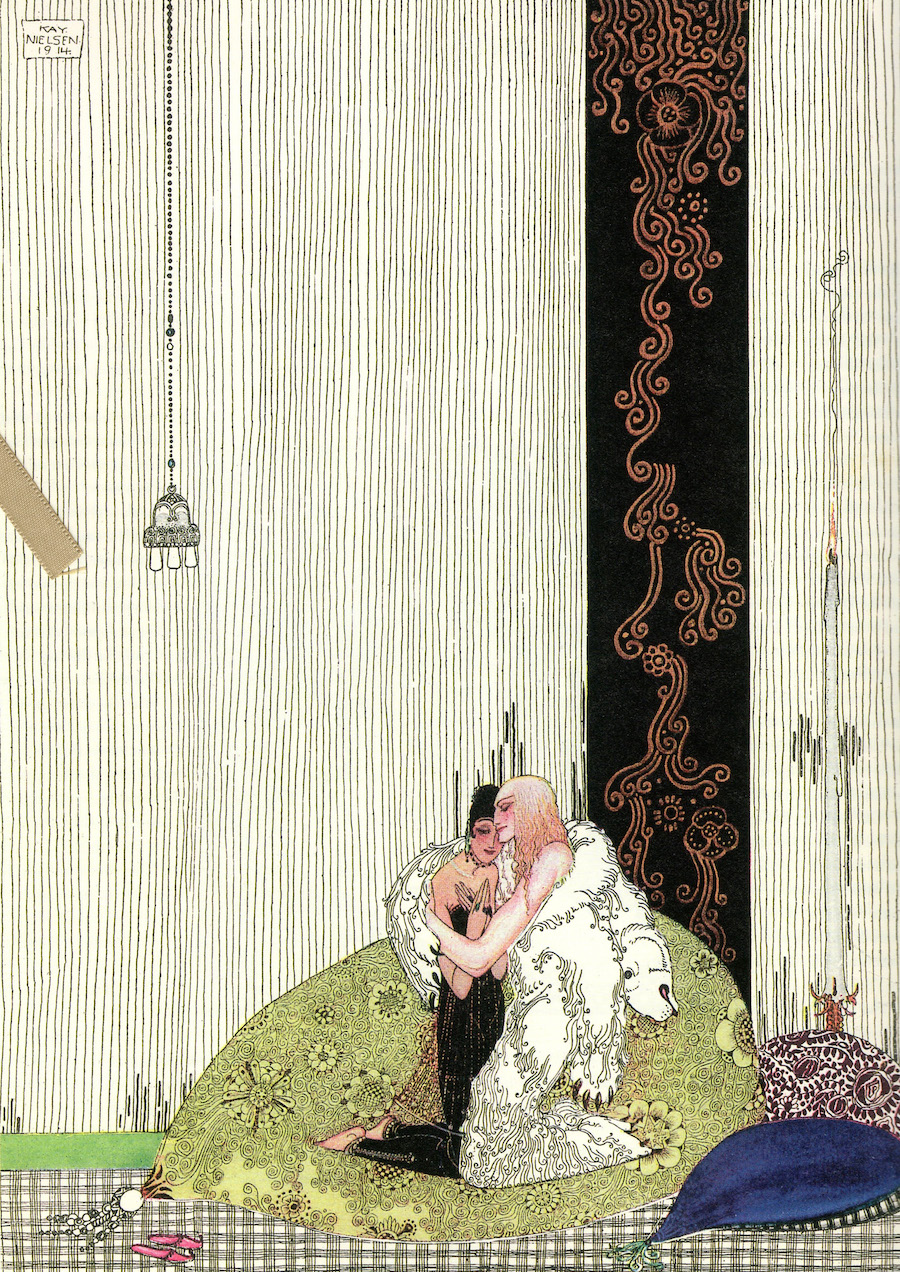

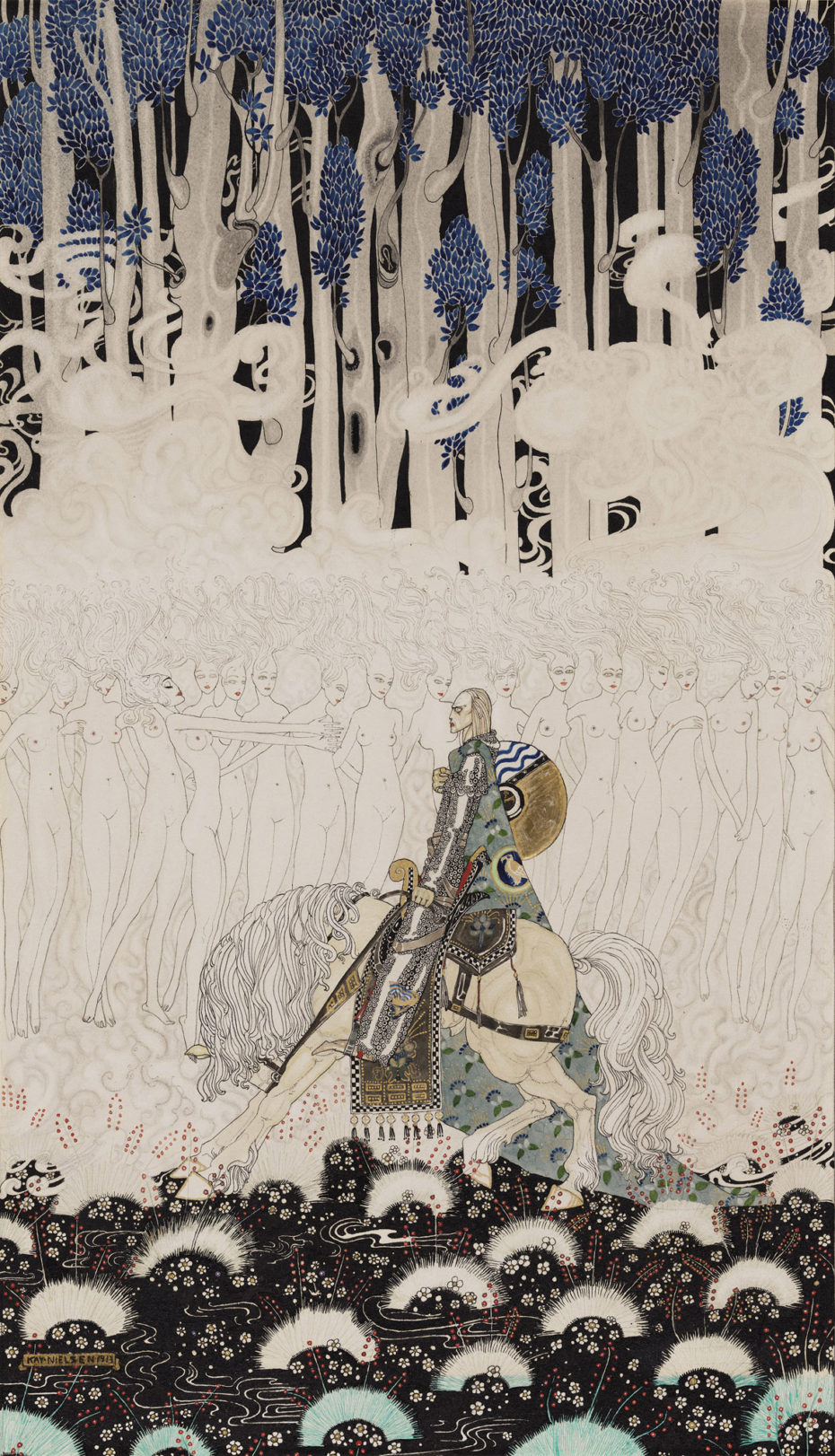

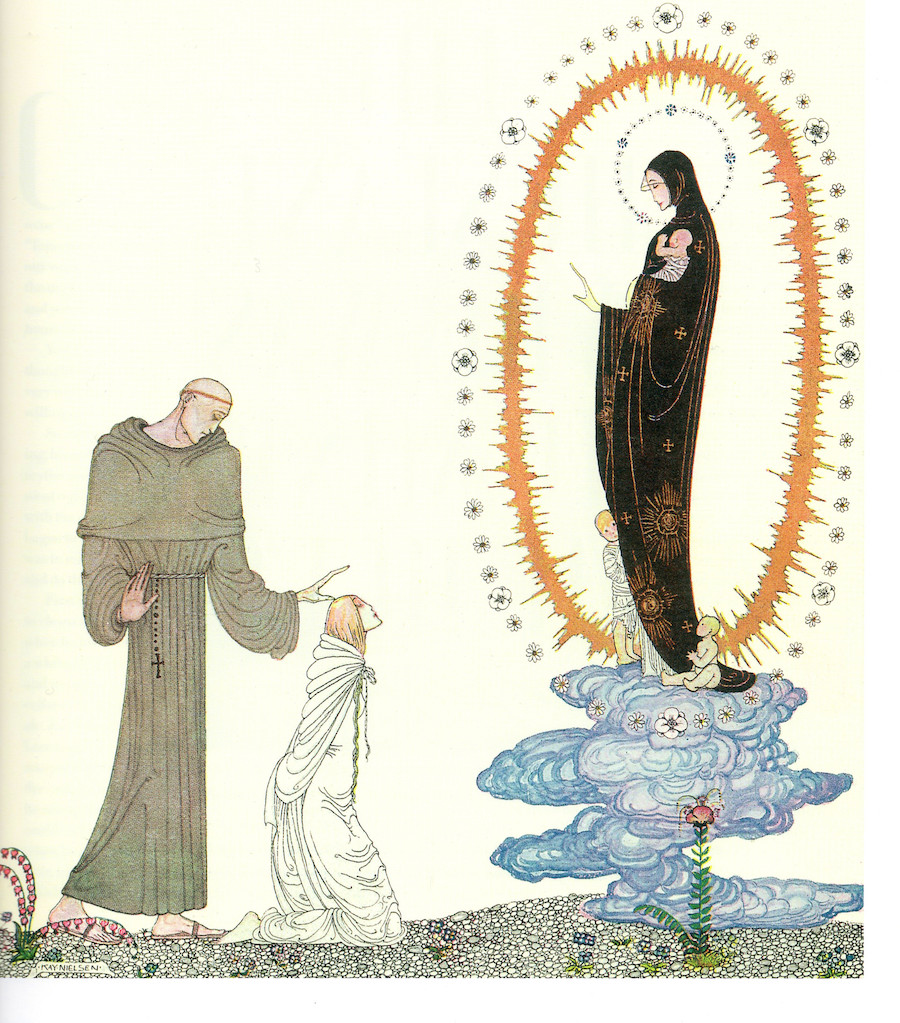

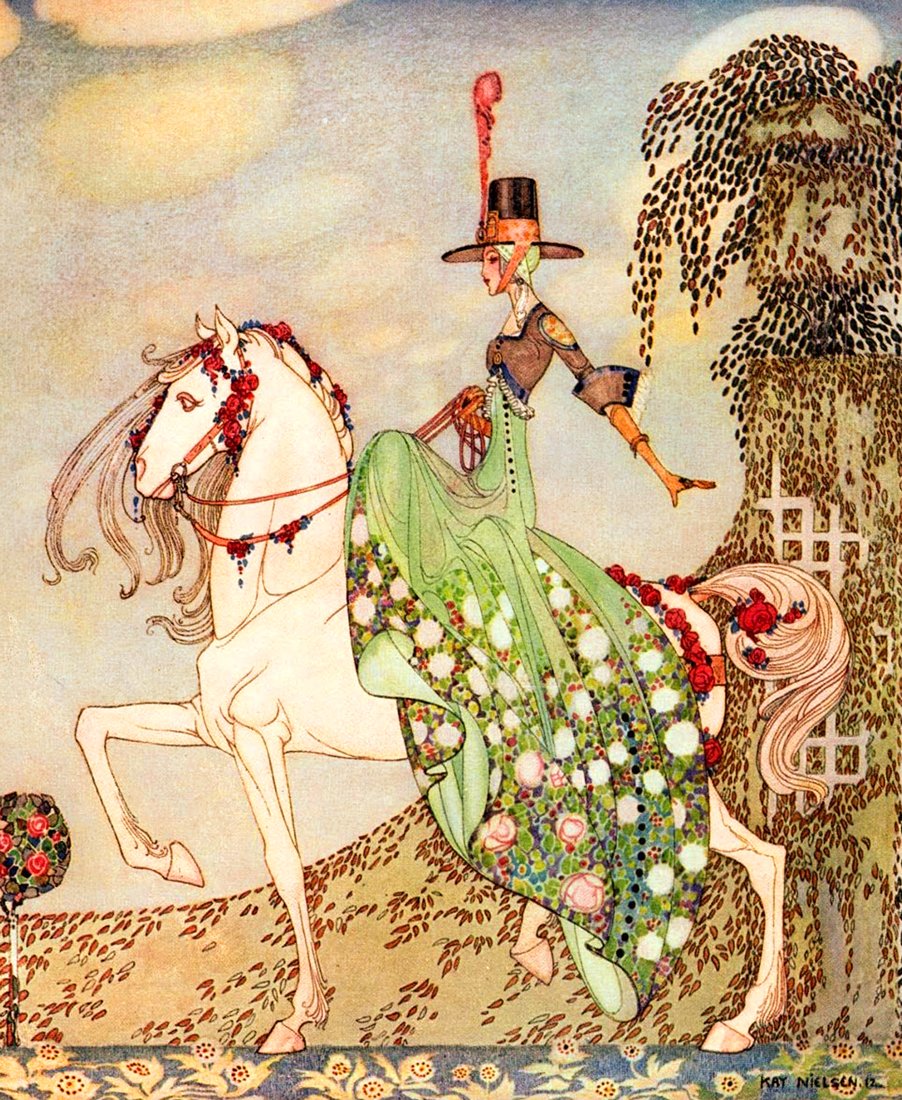

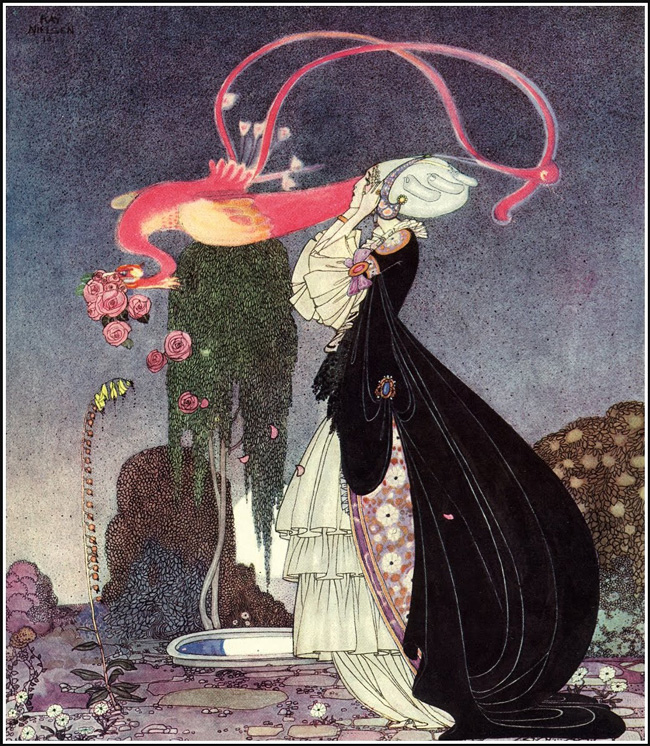

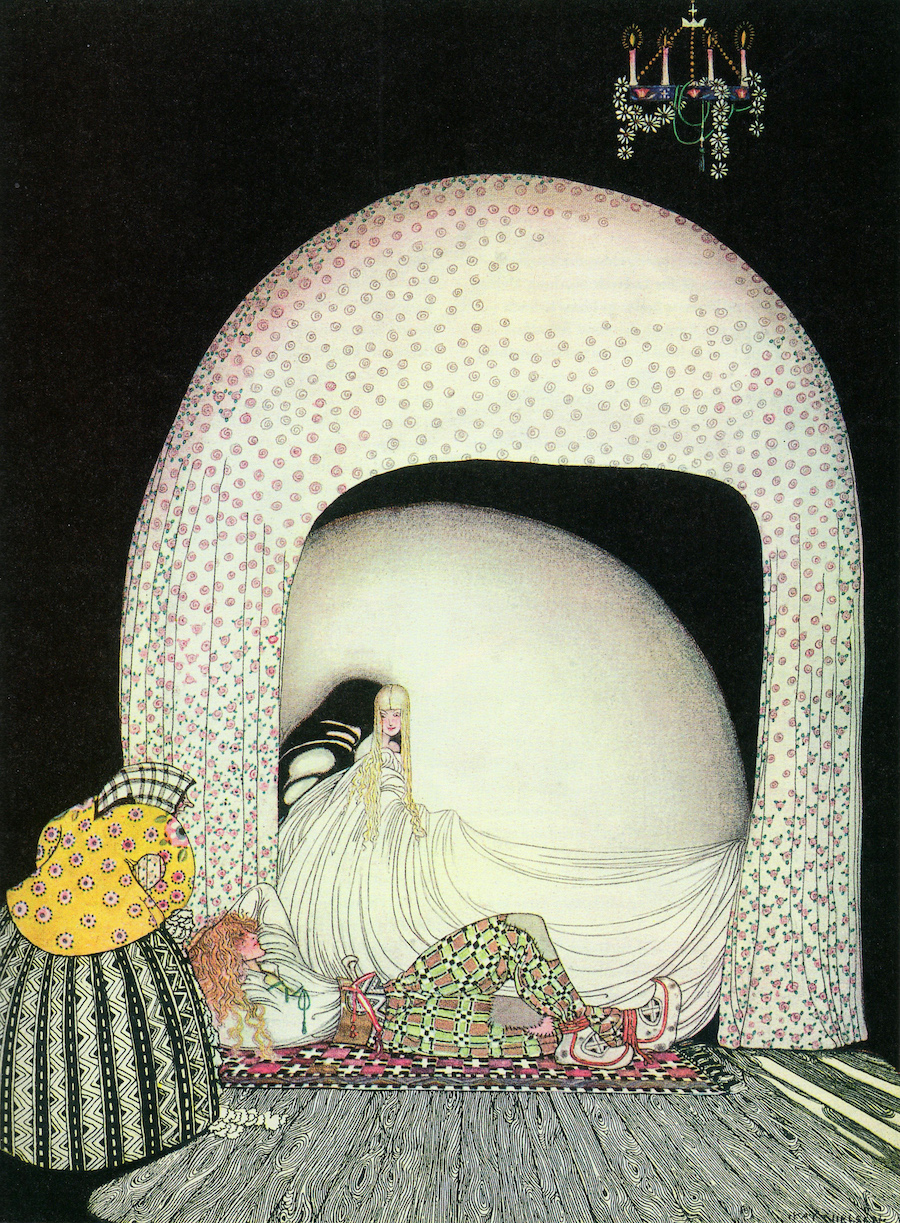

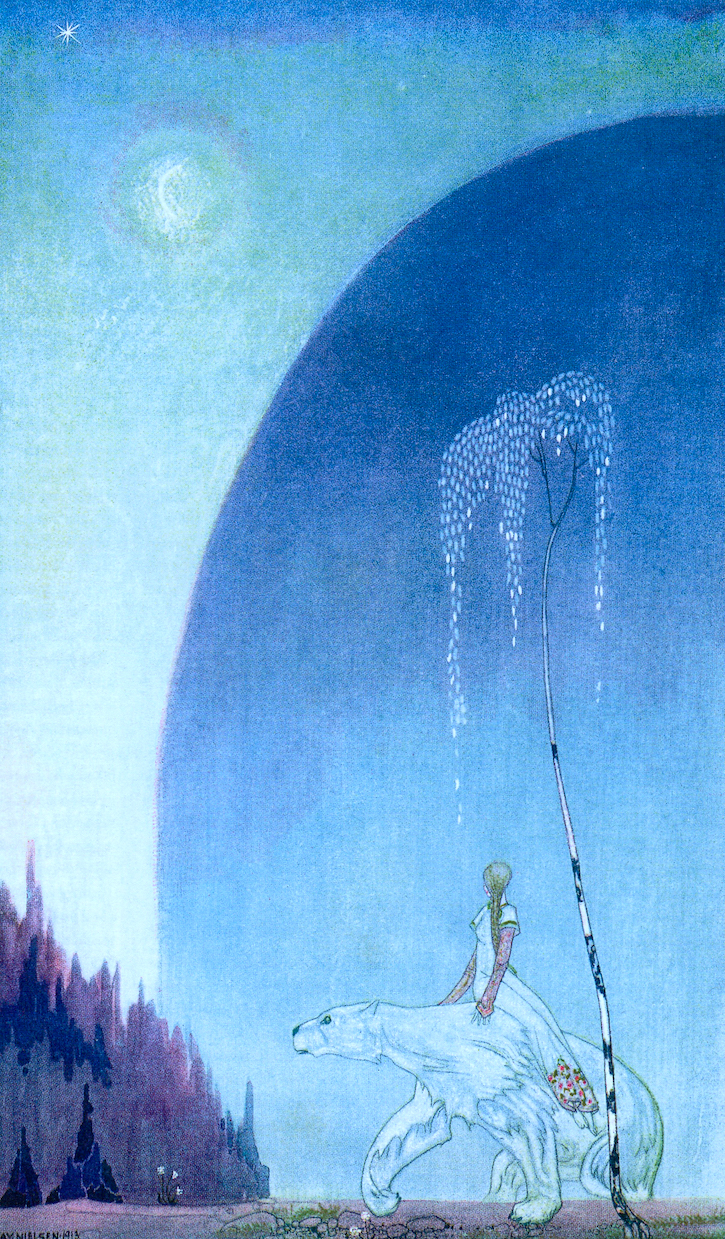

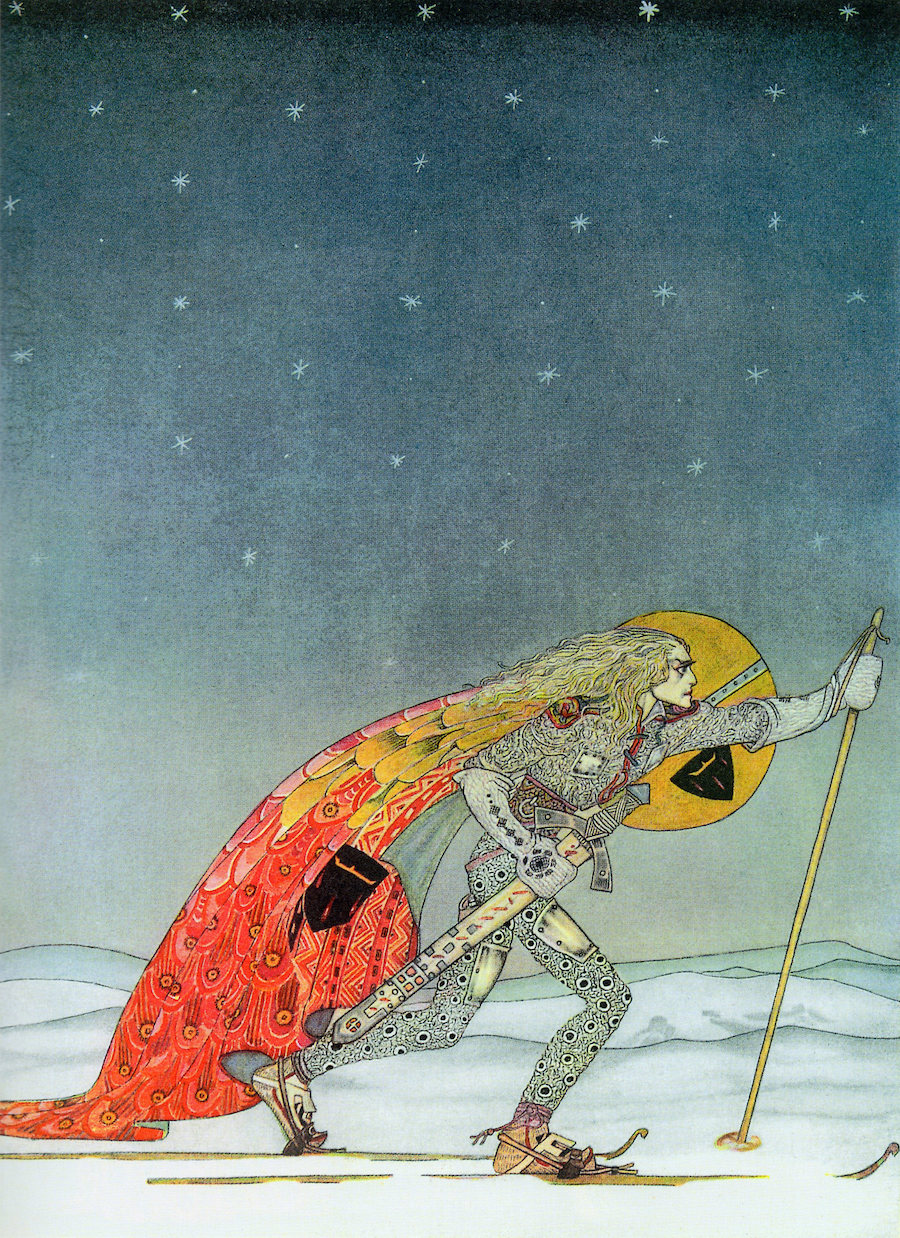

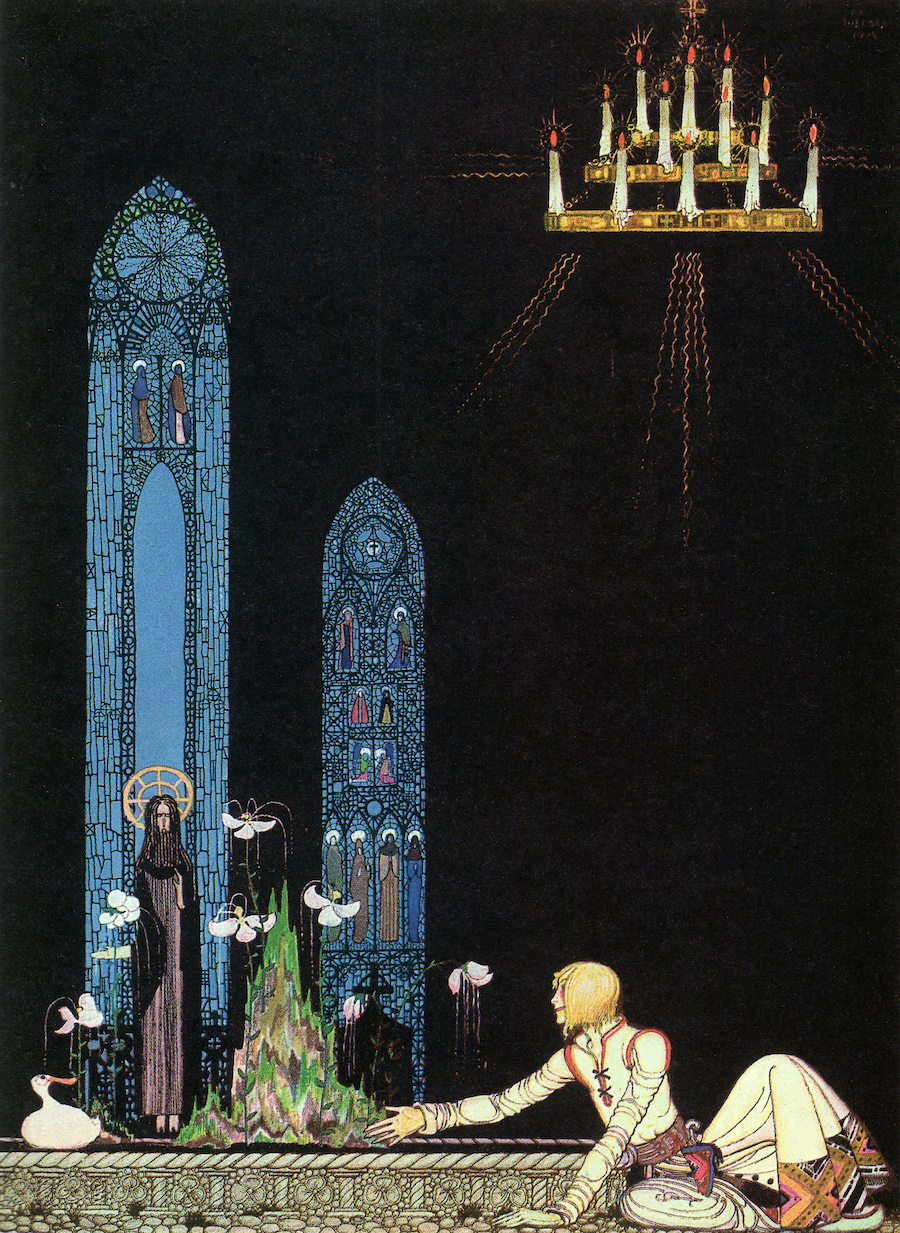

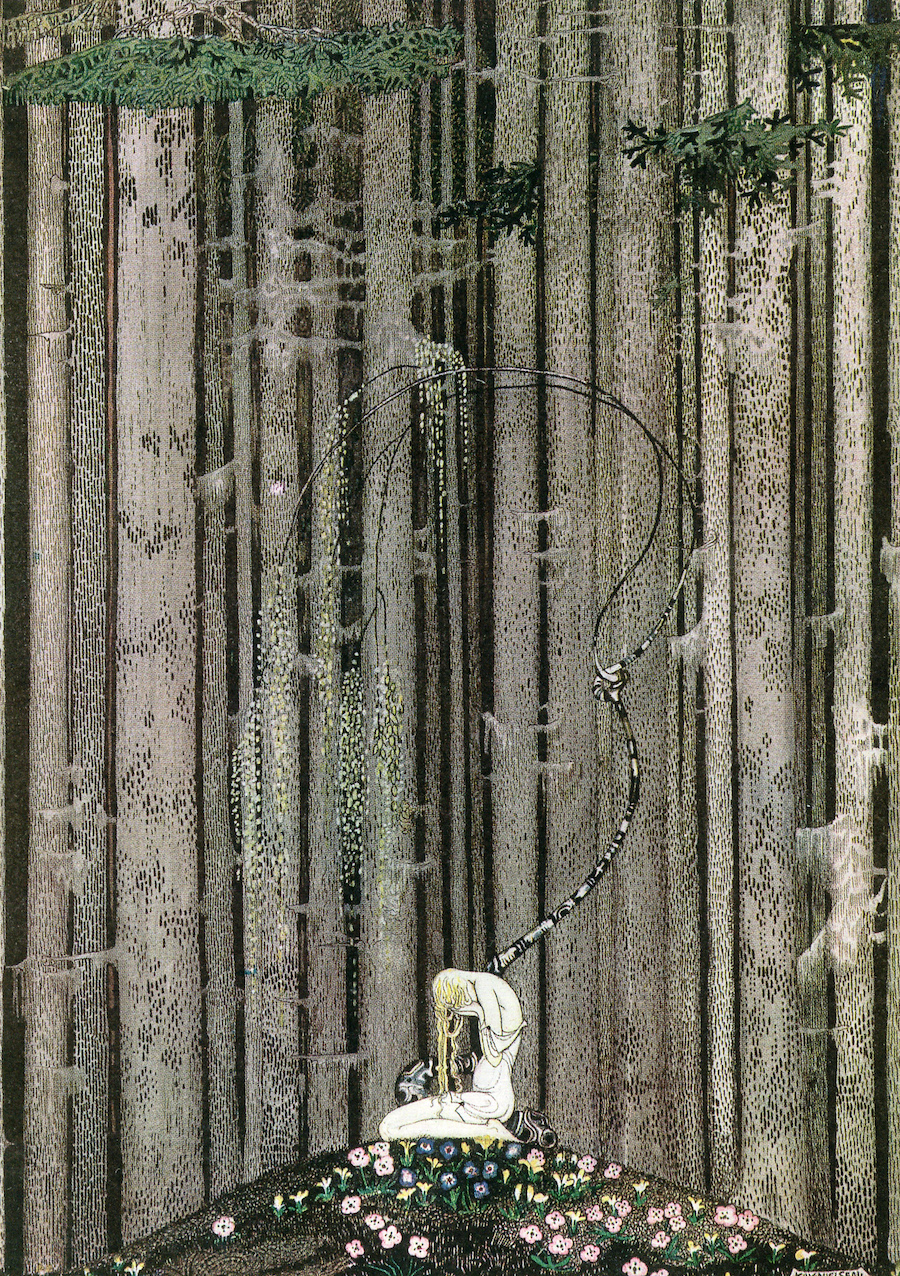

Nielsen was born in 1886 in Copenhagen, Denmark, to thespian parents, which may explain his flair for the dramatic. He studied art in Paris at prestigious institutions like the Académie Julian, and received his first commission for a book called In Powder and Crinoline: Fairy Tales Retold by Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch in 1913, and East of the Sun and West of the Moon a year later. Today, it’s considered one of his most celebrated works; there’s an air of Asian influence in his scenes – not unlike those of illustrator Errol Le Cain – and a lush dose of Art Nouveau. The arabesque lines are so delicate, they look as if they’d been carved into thin air with his pen. And those clothes…

The world went wild for Nielsen, who captured both the whimsy and dark undercurrents of so many old fables (like Fairy Tales by Hans Andersen in 1924). He began dabbling in theatre set design, and even exhibited his work in New York, enchanting the public with these worlds that seemed to come alive at twilight.

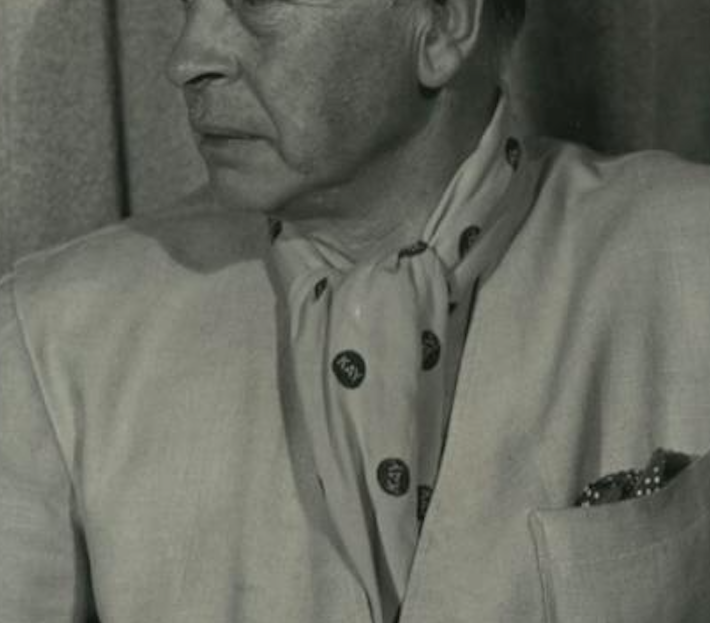

But what kind of man was Nielsen? Certainly a fashionable one. We’d wager the quietly eccentric variety. The kind who wears a tie bearing his last name:

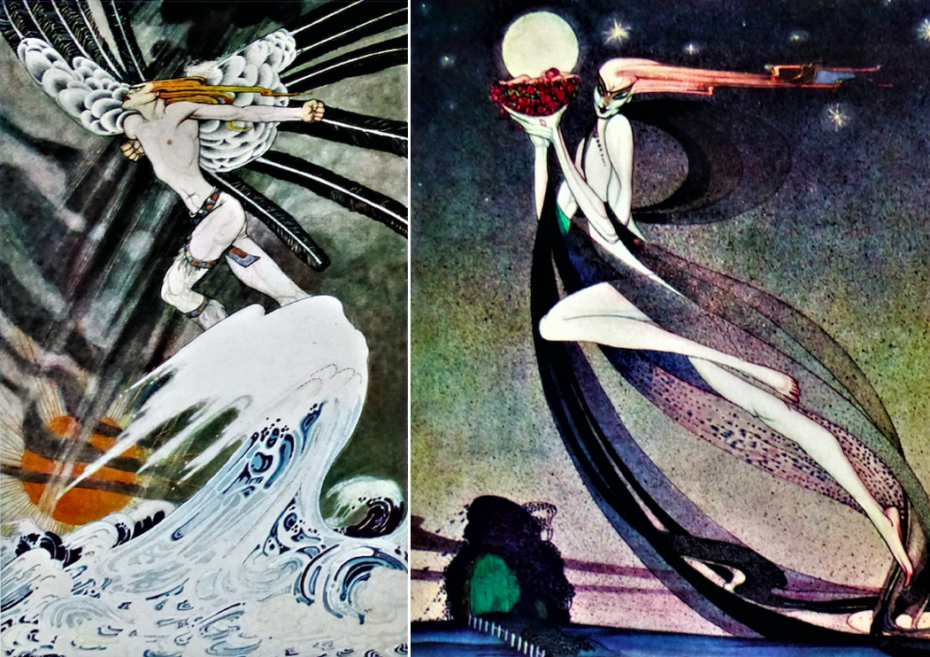

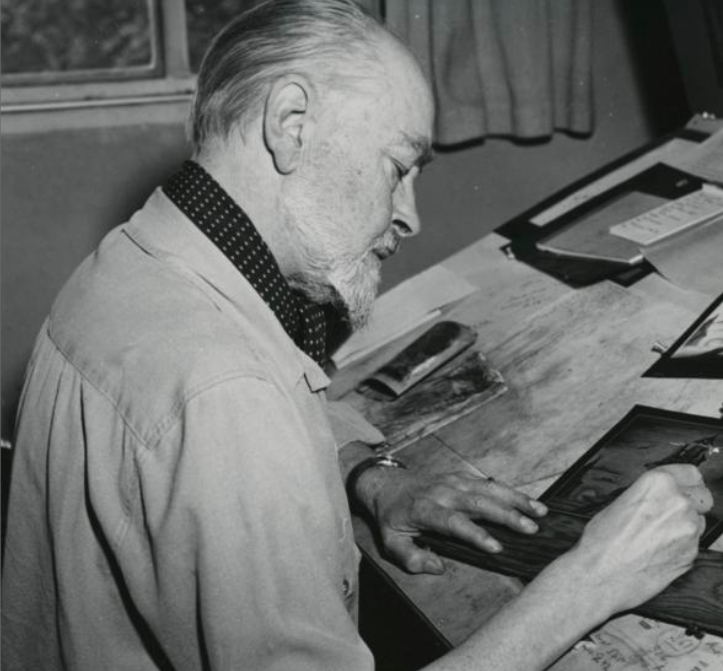

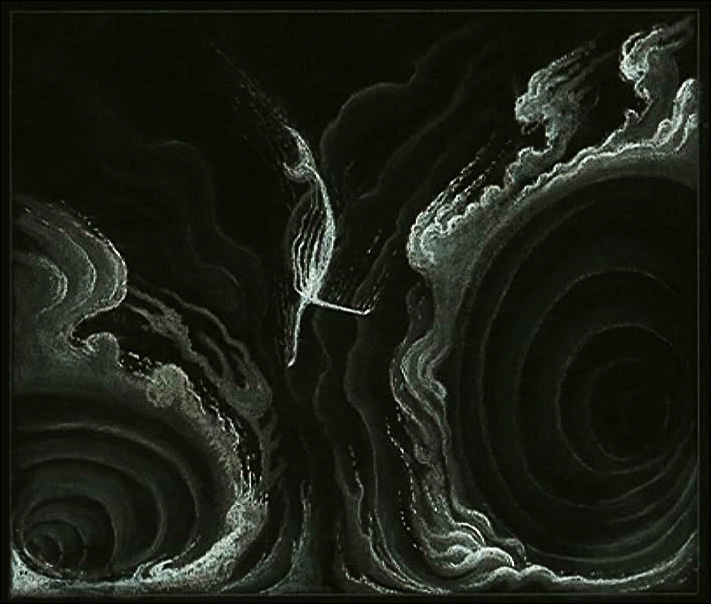

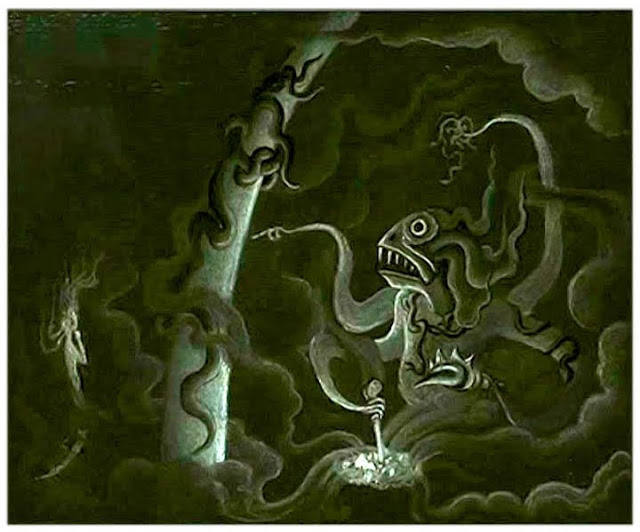

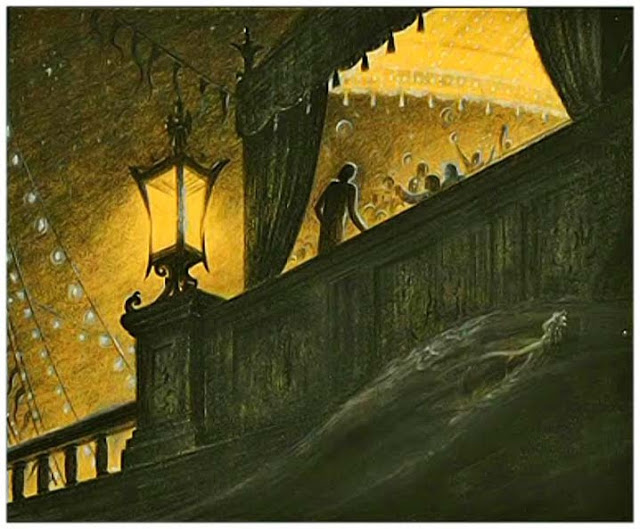

By the late 1930s, Nielsen was living in Hollywood and working for various studios in California. On the personal recommendation of a friend, he was hired by Walt himself to work for The Disney Corporation, and dreamt up the très spooky “Night on Bald Mountain” sequence in Fantasia (1940):

Disney, in a relatively short career (1937-41) that includes illustrating for Fantasia (1940):

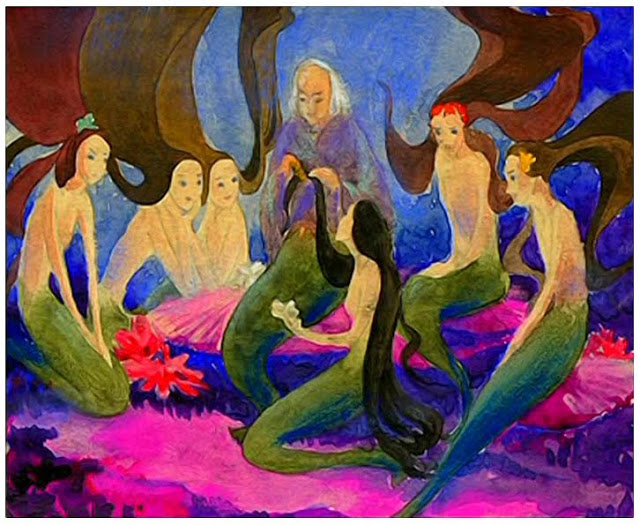

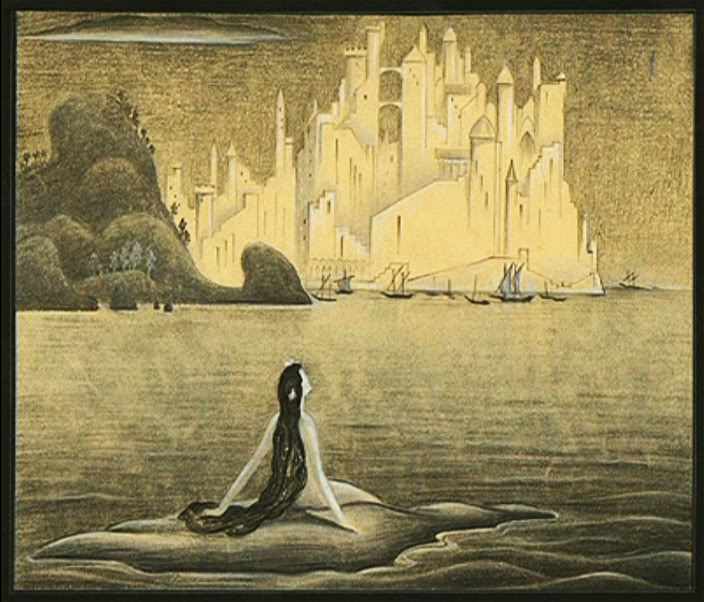

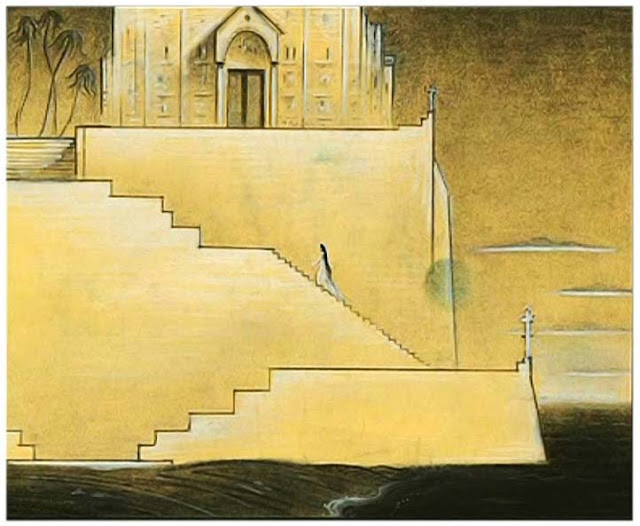

He also completed concept drawings for 1989’s The Little Mermaid that would end up having a heavy influence the look of the film 30 years later…

Unfortunately, Disney let Nielsen go after just four years. In They Drew As they Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney’s Musical Years we learn why. “As the war closed foreign territories Disney released, the Studio looked for ways to limit the cost of future productions,” writes author Didier Ghez, “[Nielsen] found that his detailed perfectionism, once so valuable on Fantasia, was now viewed as liability.” He didn’t abide by production deadlines, preferring to work slowly and let his drawings reveal themselves to him in their own time. It’s terribly romantic. But alas, not very economical. Still, given that Disney was consulting his storyboards for The Little Mermaid decades later, the mind reels of what might’ve been had they held onto him a little longer…

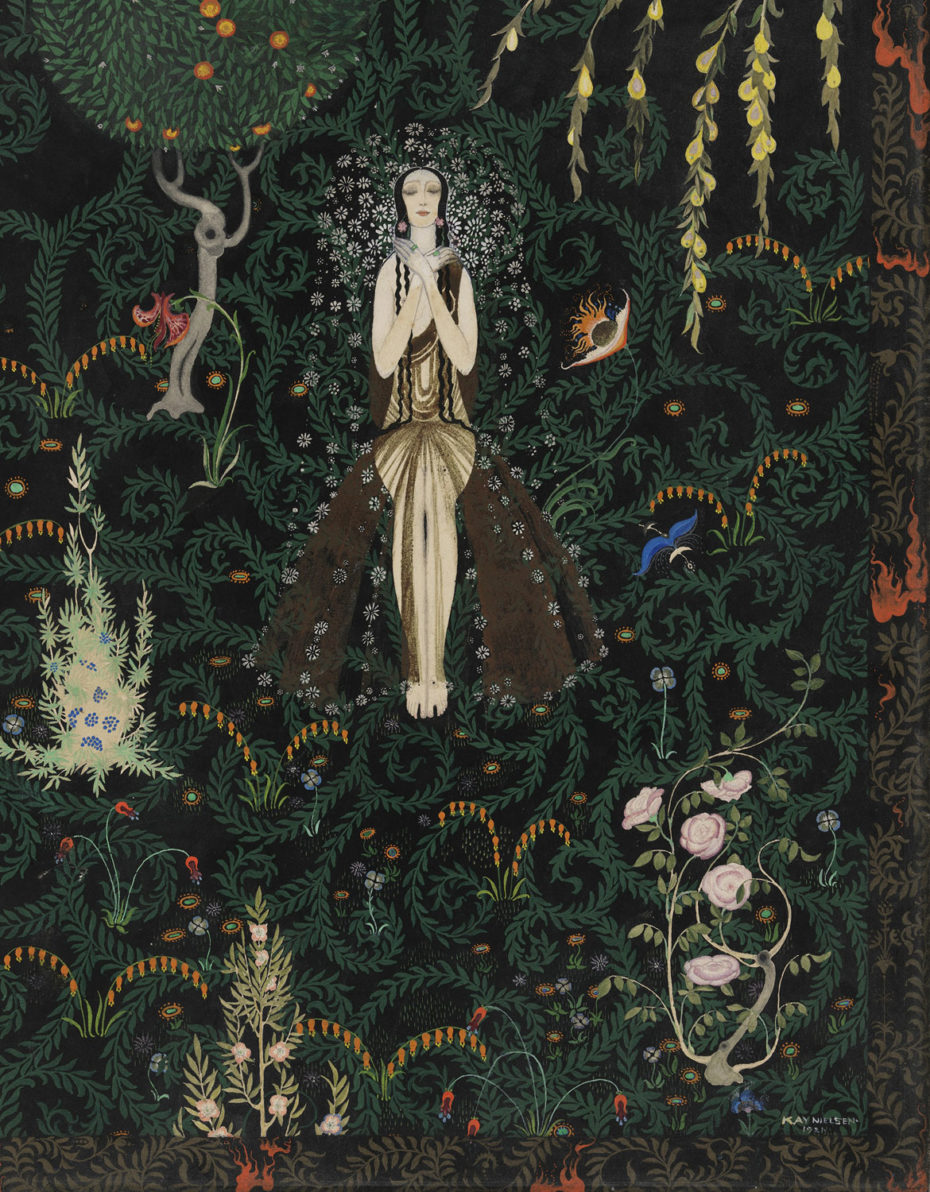

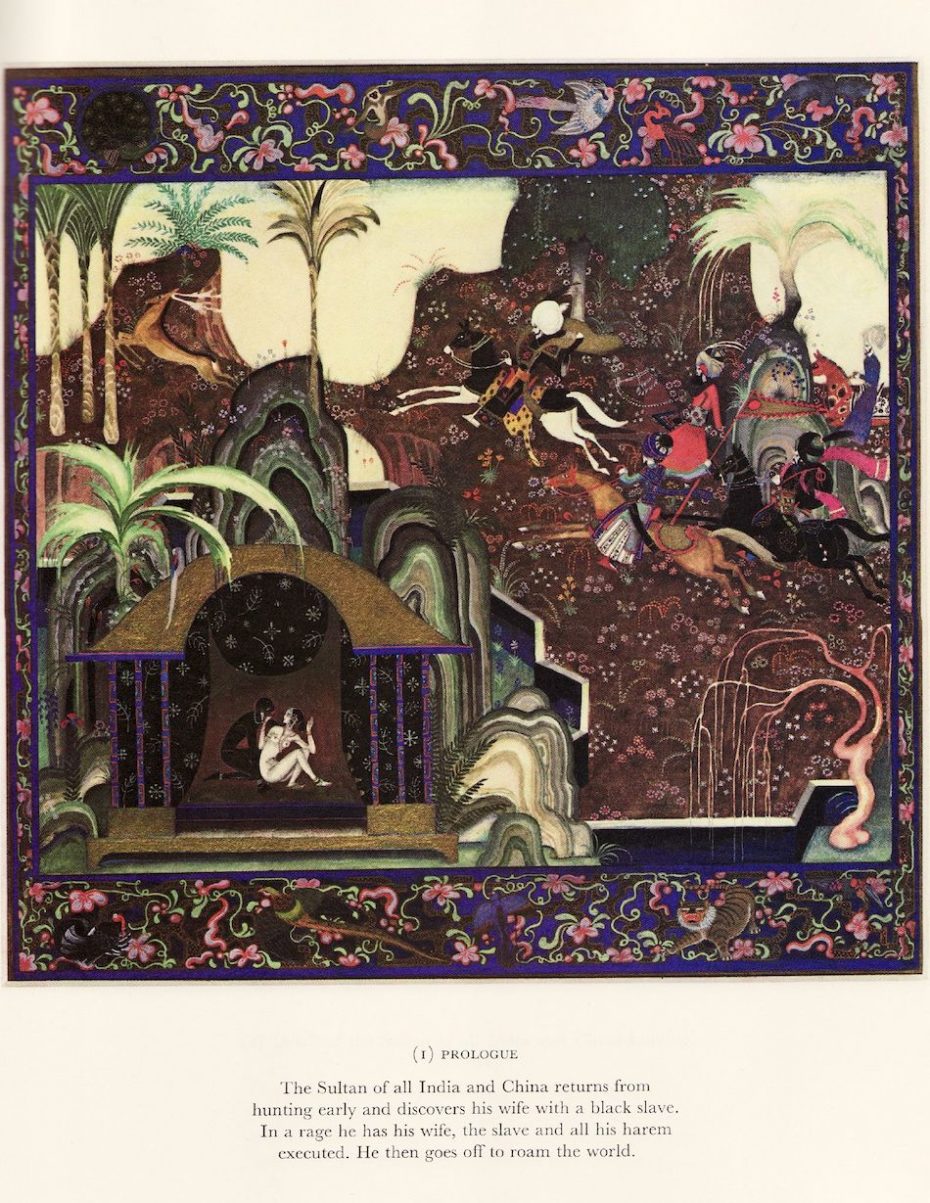

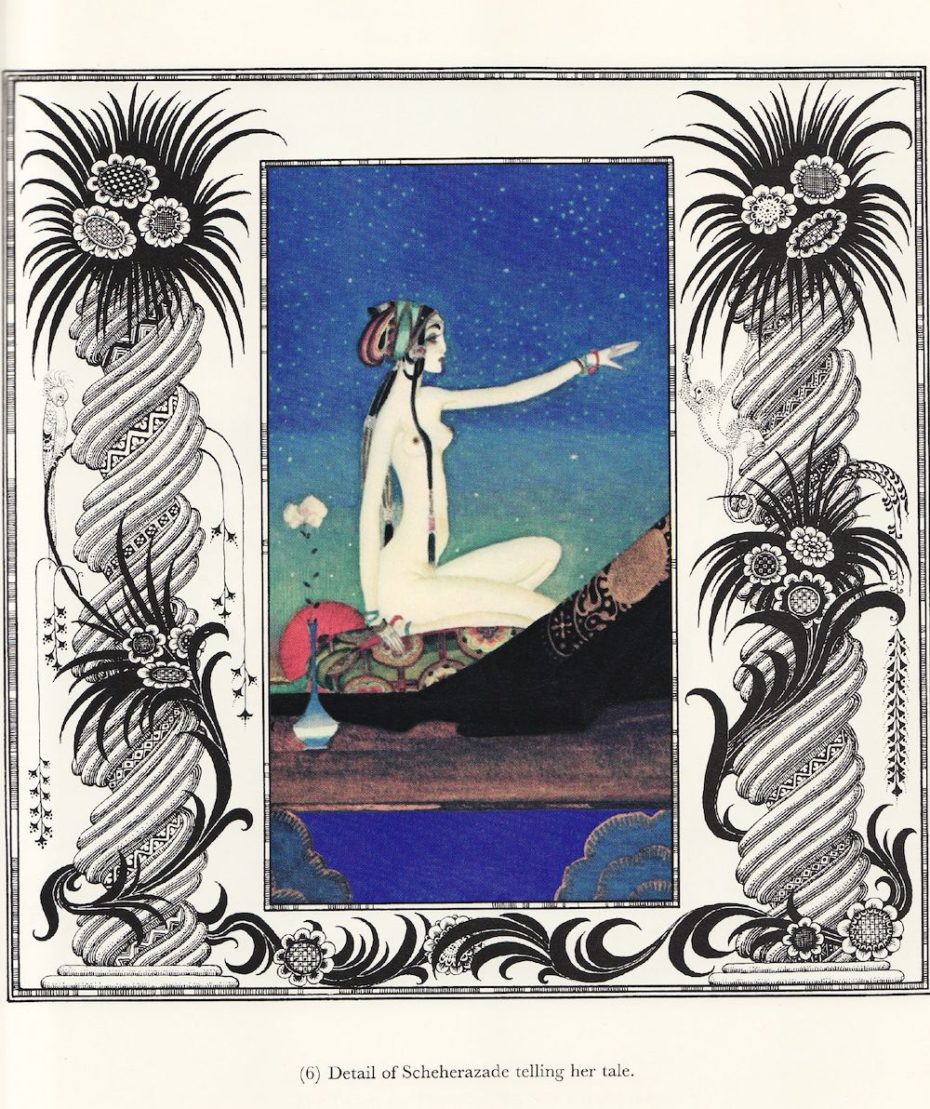

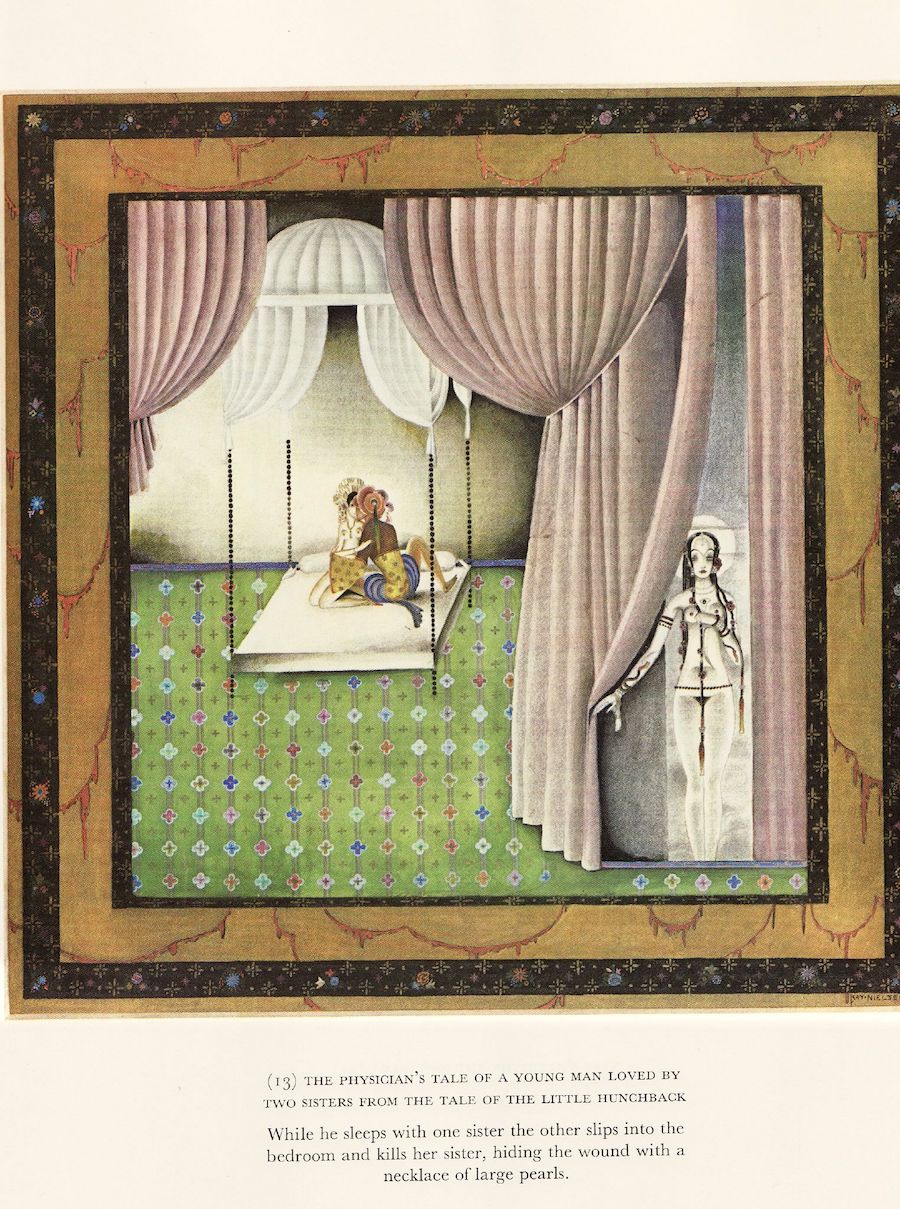

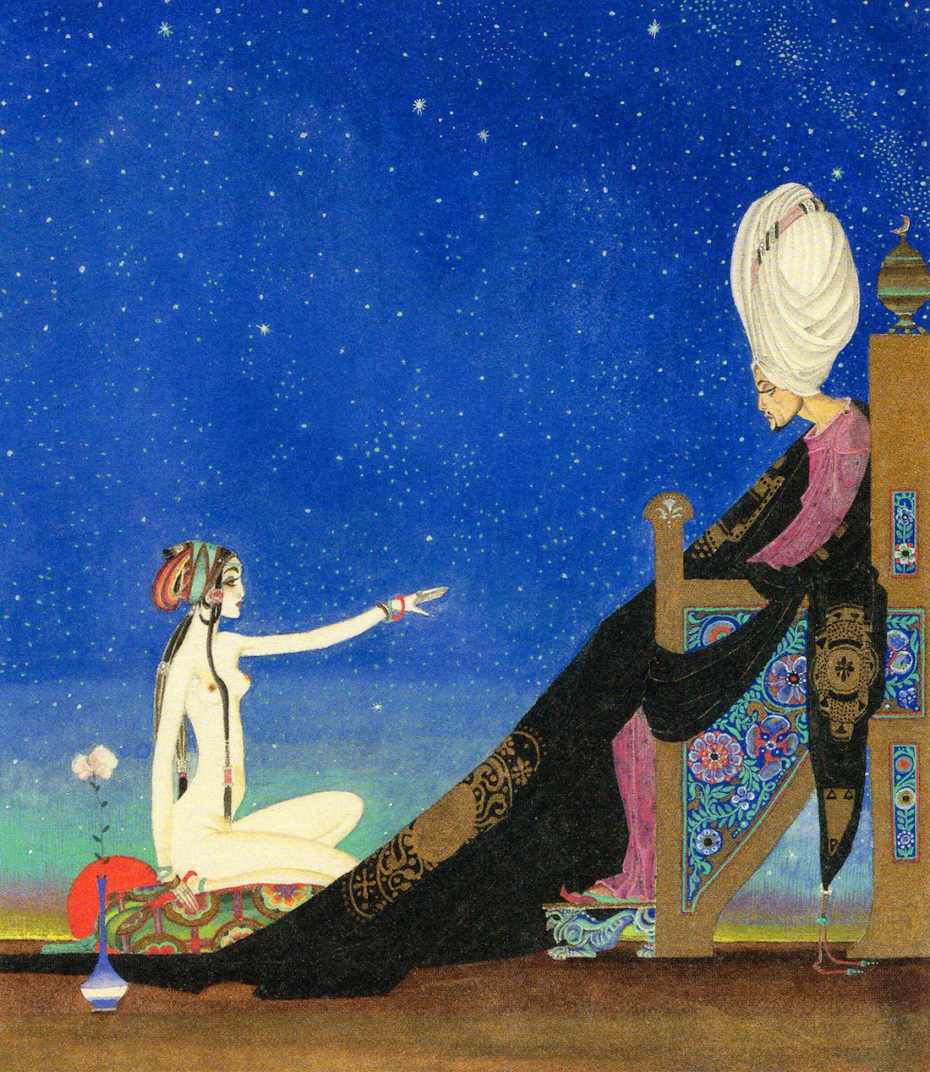

In an interview with Contemporary Illustrators of Children’s Books in 1930, Nielsen cites the knife-twisting genius of “men such as [Henrik] Ibsen” as his inspiration. “Since early boyhood I have been drawing,” he says, “Anything I heard about I tried to put in situations on paper […] I remember I loved the Chinese drawings and carvings in my mother’s room. My artistic wandering started with the early Italians over Persia, India, to China.” Though he was one of the most prominent illustrators out there, he did have some posthumously released works, like A Thousand and One Nights, (1917-1919):

Call us biased, but it’s Nielsen’s bluer hues that tug on our heartstrings the most…

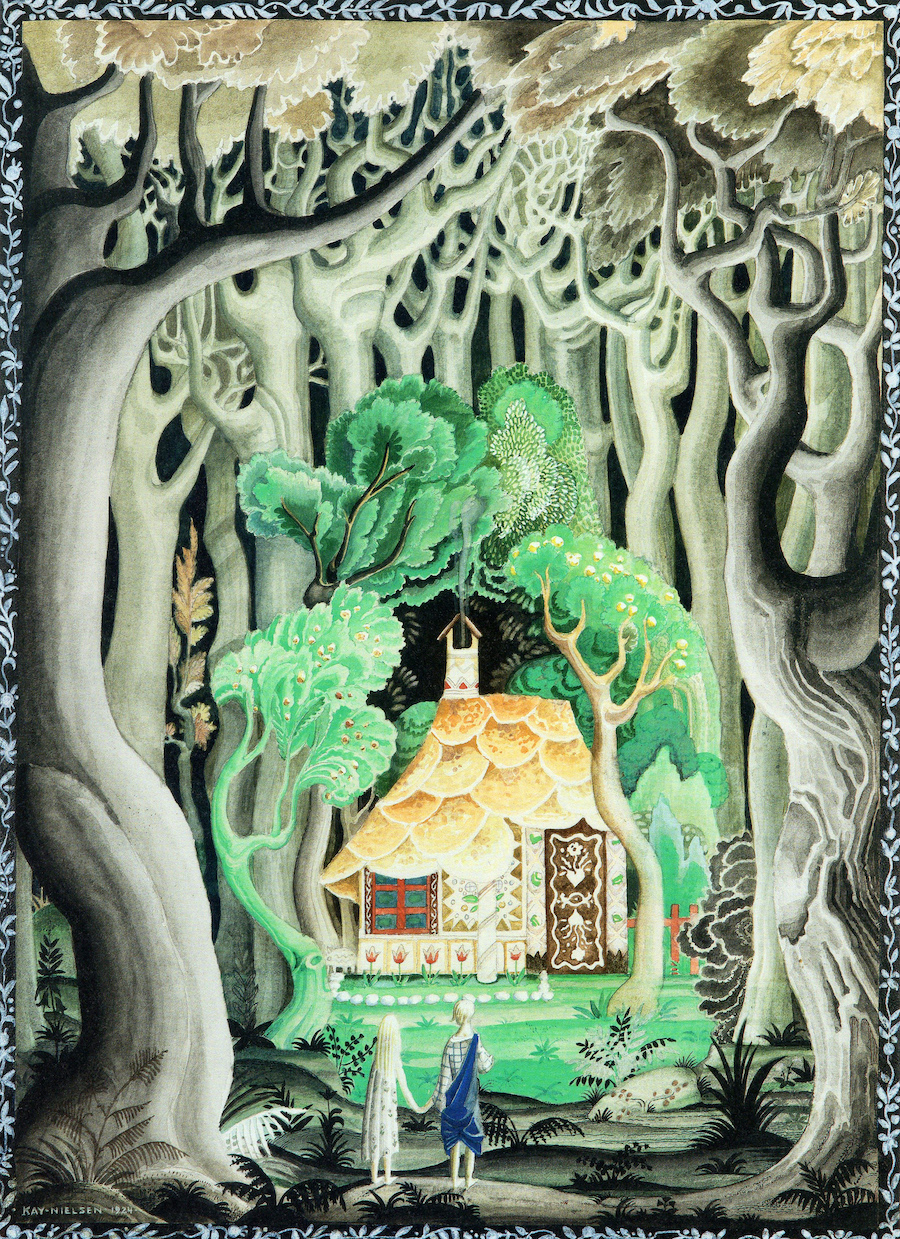

There’s an equal sense of tranquility and intrigue in those nightfall scenes. The feeling that something wonderful, albeit with a streak of the wicked, is on its way. And isn’t that what makes for the most memorable fairytales? Just ask the OG Little Mermaid, in which our gal ends up stabbing herself, or the blatant child-munching of Hansel and Gretel. We’ve got a whole compendium f*cked up bedtime stories. Nielsen just had an instinct for making that (bitter) sweet spot shine.

TASCHEN’s centenary reproduction of East of the Sun and West of the Moon revives a classic collection of 15 Norse folktales illustrated by the beloved Danish artist Kay Nielsen.