“I think I’m the first man to sit on top of the world,” is not something many people can boast, especially if they lead perfectly normal lives, say, working a desk job in the city in relative anonymity. But for many years, that was the truth of Matthew Henson.

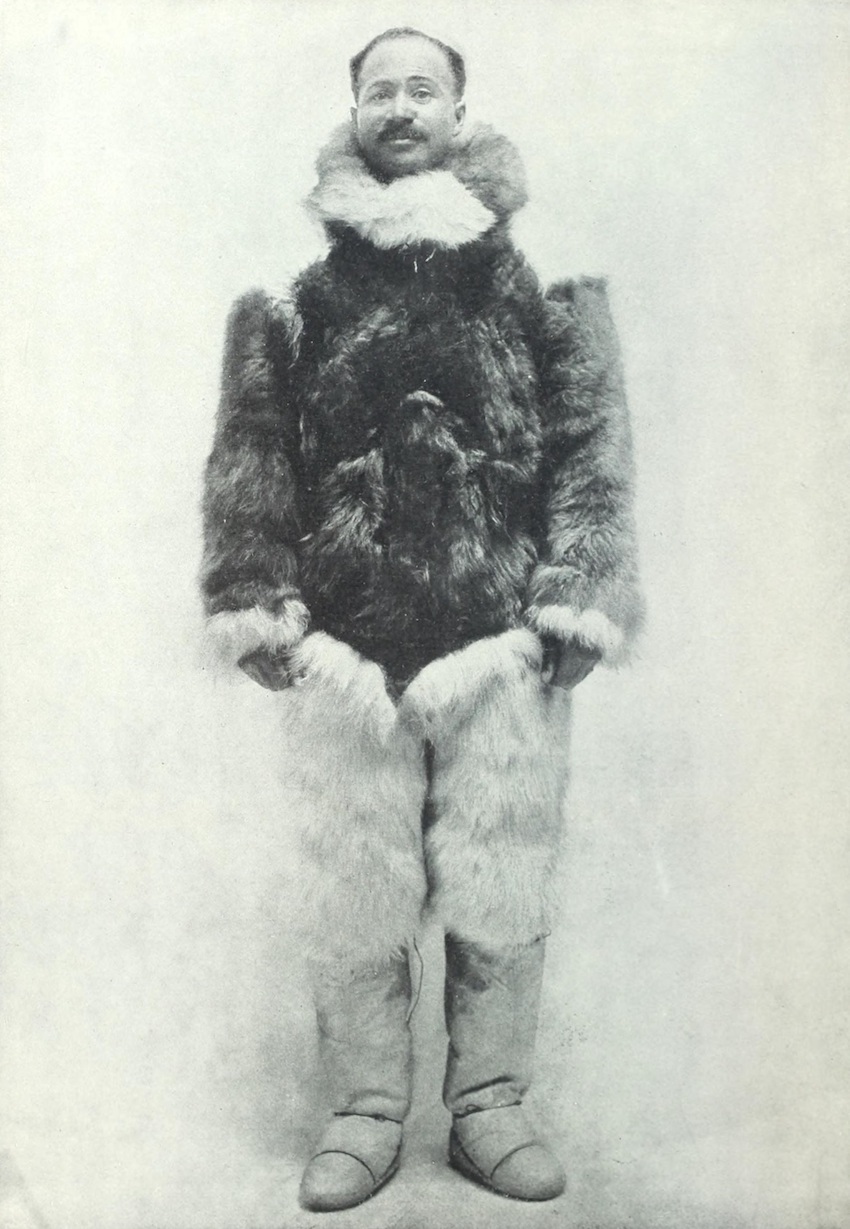

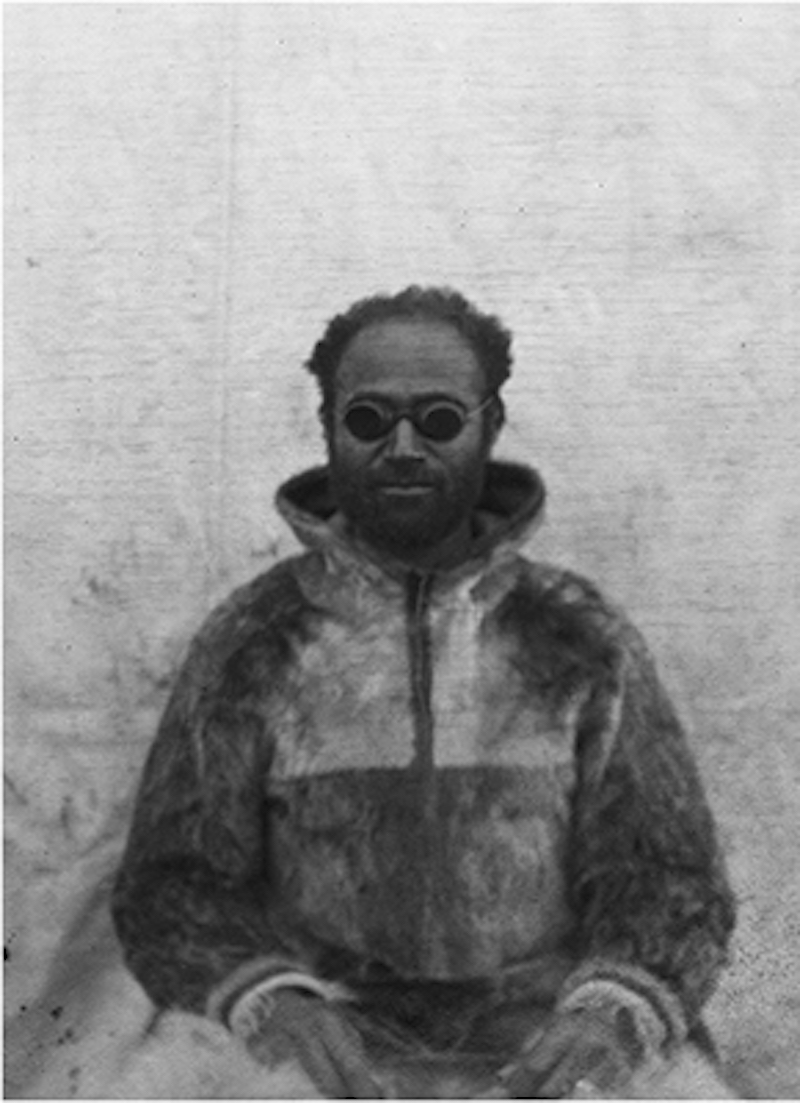

In 1908, the unsung African American explorer was the first of a six-man team to reach the North Pole. He studied and spoke Inuktitut better than any other Westerner on the expedition, leading to successful trade and navigation relations with the local Inuit. He built Igloos, trained the dog sled crews, studied indigenous survival techniques, and mastered a lot of the painstaking, behind-the-scenes work that came with being the personal valet of a wealthy white explorer who had something to prove to the boys back home at the National Geographic Society. It’s easy to be floored by Henson’s accomplishments, which, aside from being achieved in -29 degree temperatures, show the breadth of what it takes to be an explorer. But it’s not so easy to understand how he spent decades following the expedition that should have changed his life forever, unrecognised and unrewarded. So as we conclude Black History Month, we’d like to raise a glass and share the story of our adventurer du jour…

Matthew Henson and the man who’s officially credited with reaching the North Pole first – Robert Peary – met in a gentlemen’s clothing store in 1887, where a 21 year-old Henson was working at the time in Washington, D.C. As he waited on Peary, a Navy engineer with grand ambitions, the two men from very different backgrounds began talking. Peary would learn that Henson was born into a family of free sharecroppers in Maryland, but had to flee the state after his parents were targeted by the Klu Klux Klan. By the age of twelve, he had gone to sea as a cabin boy and travelled to ports as far as China, Japan, Africa, and the Russian Arctic seas. The merchant ship’s captain had taken the young African American under his wing and taught him to read and write.

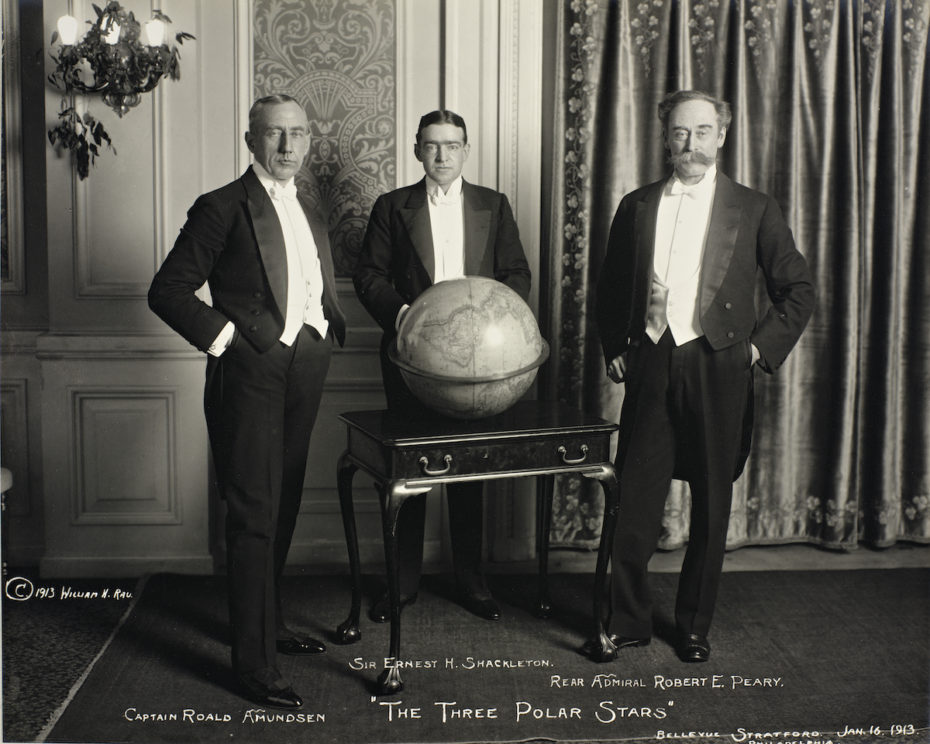

It’s safe to say that Henson had more experience than many of the aspiring explorers Robert Peary was used to meeting in the gentlemen’s lounge of the Nat Geo Society at the turn of the century. Peary (the guy pictured below on the far right with the walrus moustache) hired him on the spot.

From that point forward, Henson went on every expedition Peary embarked on; trekking through the jungles of Nicaragua and, later, covering thousands of miles of ice in dog sleds to the North Pole.

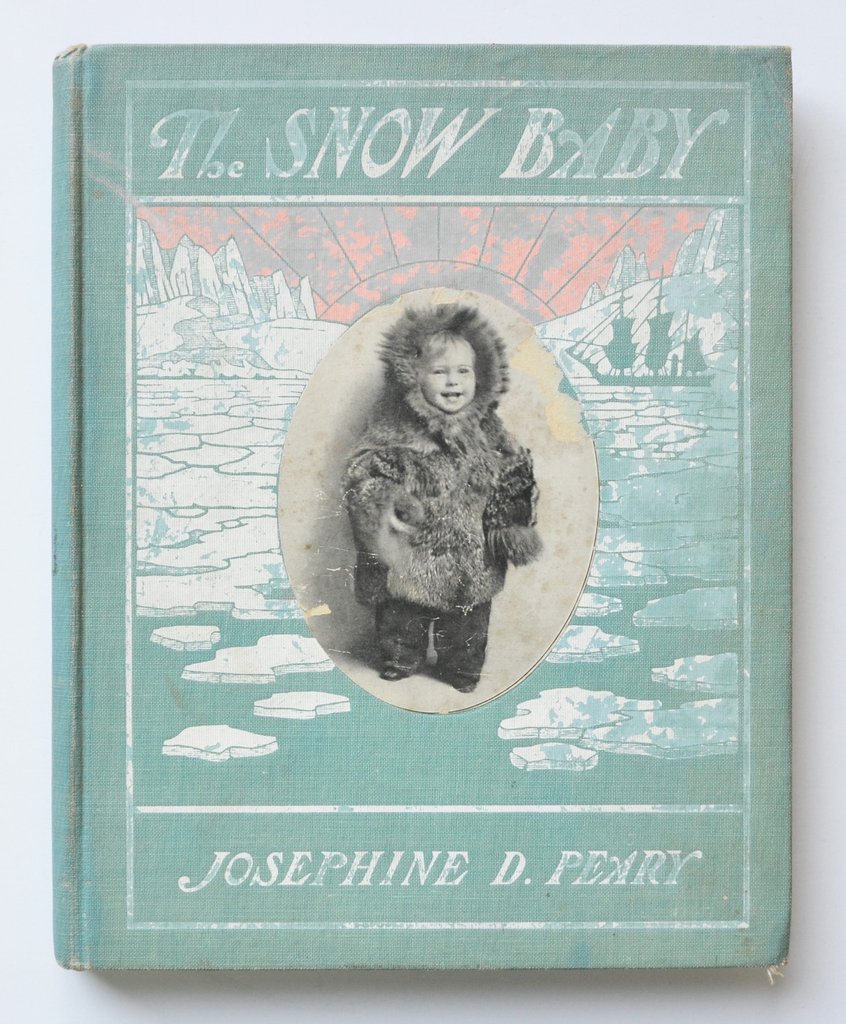

On a side note, this would be a good time to mention that Robert Peary’s wife, Josephine, AKA the “First Lady of the Arctic” and one of history’s bravest, corset-wearing ice queen explorers, was also a notable party member of Peary’s expeditions. She actually gave birth to their baby by the North Pole, and wrote a best-selling book, The Snow Baby:

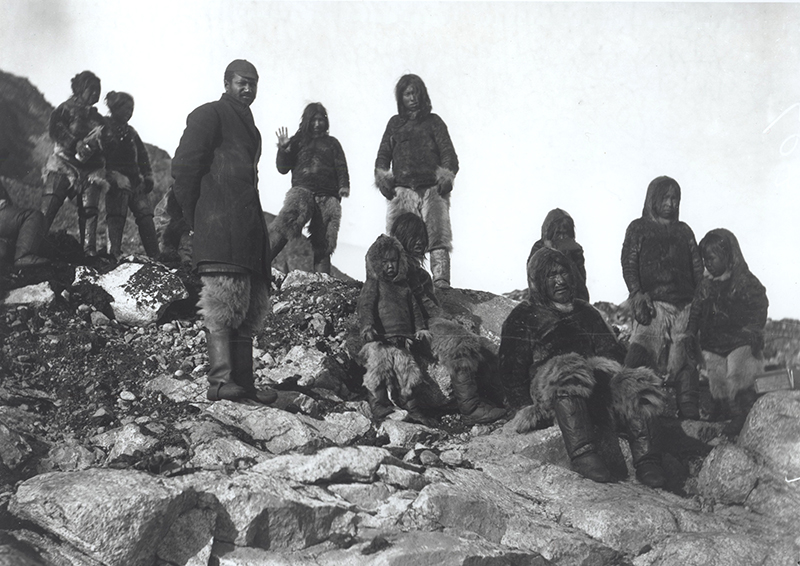

In short, Commodore Peary was rolling with a very intimate but diverse crew that included “22 Inuit men, 17 Inuit women, 10 children, 246 dogs, 70 tons (64 metric tons) of whale meat from Labrador, the meat and blubber of 50 walruses, hunting equipment, and tons of coal”.

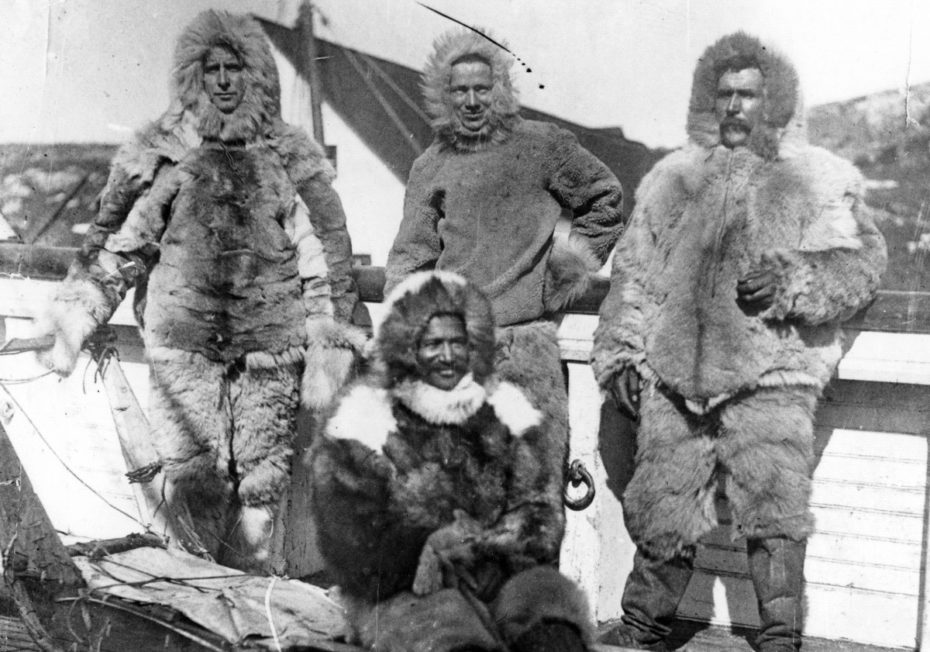

Henson was promoted to “first man” and field assistant. He was a skilled craftsman, often coming up with life-saving solutions for the team in the harshest of Arctic conditions. On the final stage of the journey toward the North Pole, it was just himself, Peary and four native Inuit assistants, Ootah, Egigingwah, Seegloo, and Ooqueah.

As they approached the “Farthest North” point of any Arctic expedition until 1909, Robert grew more and more weary, suffering from exhaustion and frozen toes, unable to leave their camp, set up five miles from the pole. Henson scouted ahead on Peary’s orders. “I was in the lead that had overshot the mark a couple of miles,” Henson later recalled, “We went back then and I could see that my footprints were the first at the spot.”

According to his account of their eighth attempt to reach the North Pole (which is now suspected to be off the mark by a wee bit, but who’s trimming inches), Henson revealed that it wasn’t Admiral Peary, the great explorer who would later receive many honours for leading the expedition, but he himself, who made it to the “top of the world” first.

When Peary caught up with him, the sled-bound Admiral allegedly trudged up to plant the American flag in the ice – and yet, the only photograph of the historic moment shows a crew of faces that are distinctly not white.

Was it Robert’s way of honouring the crew by allowing them to pose for the snap? Or was he still back at camp, unable to make it the last few miles, leaving his “first man” to plant the flag and take a self-portrait with the four Inuit team members? These may seem like minor details, but if it was you that had planted the first flag on the moon, wouldn’t you want history to know it?

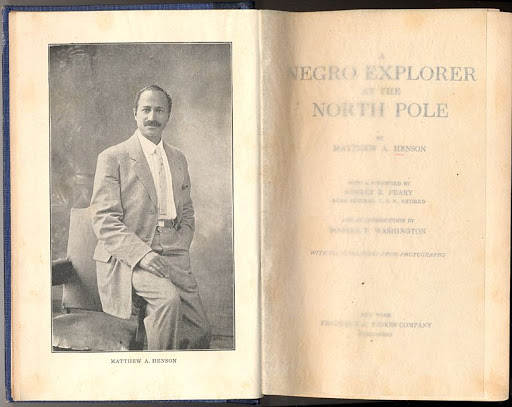

Here’s what Henson wrote about the moment they reached the North Pole in his autobiographical account, A Negro Explorer at the North Pole (1912):

“[The flag] snapped and crackled with the wind, I felt a savage joy and exultation […] Another world’s accomplishment was done and finished, and as in the past, from the beginning of history, wherever the world’s work was done by a white man, he had been accompanied by a colored man. From the building of the pyramids and the journey to the Cross, to the discovery of the new world and the discovery of the North Pole, the Negro had been the faithful and constant companion of the Caucasian, and I felt all that it was possible for me to feel, that it was I, a lowly member of my race, who had been chosen by fate to represent it, at this, almost the last of the world’s great work.”

– Matthew Henson, A Negro in the North Pole (1912)

Despite some doubts about the accuracy of the data as well as a competing claim, the National Geographic Society credited Peary with reaching the North Pole and was recognised by Congress, which awarded him the Thanks of Congress by a special act in 1911.

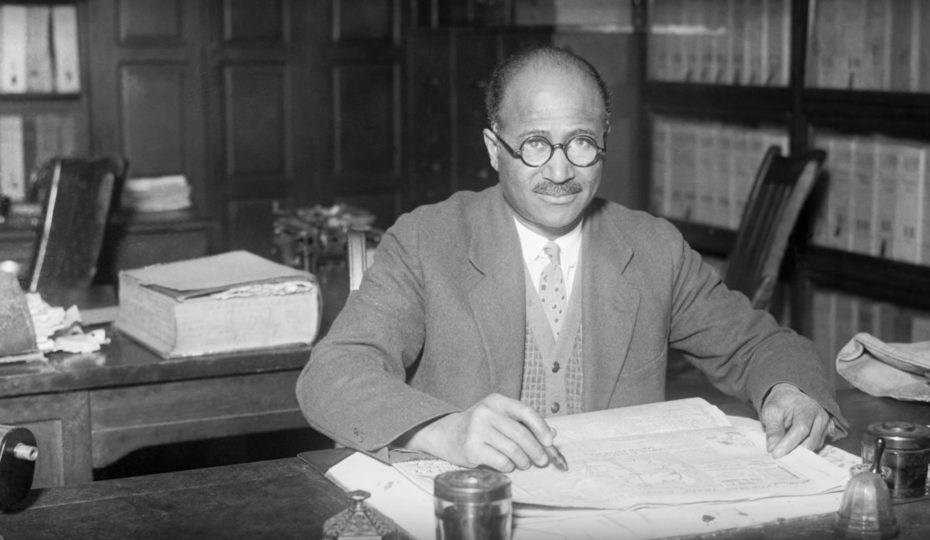

At the time, Henson’s contributions were largely ignored and, following the expedition, he returned to a very normal life, working as a clerk for 23 years on the 3rd floor of the U.S. Customs House in New York City, while Peary retired to Eagle Island. Without the reputation or financial backing to organise his own expeditions, Henson’s career as an explorer was over forever when Peary hung up his hat. In his books, Peary didn’t exactly give credit where credit was due.

“This position I have given him primarily because of his adaptability and fitness for the work and secondly on account of his loyalty,” wrote Peary. “He is a better dog driver and can handle a sledge better than any man living, except some of the best Esquimo hunters themselves.”

We can see in his own writing, that Henson struggled with the role of playing second fiddle to a man like Peary, which isn’t to say there’s not immense joy, and pride in his work with the Commodore – but there are major flashes of internalised racism in his self value. It’s complicated. It’s something I wish we talked about in high school World History classes.

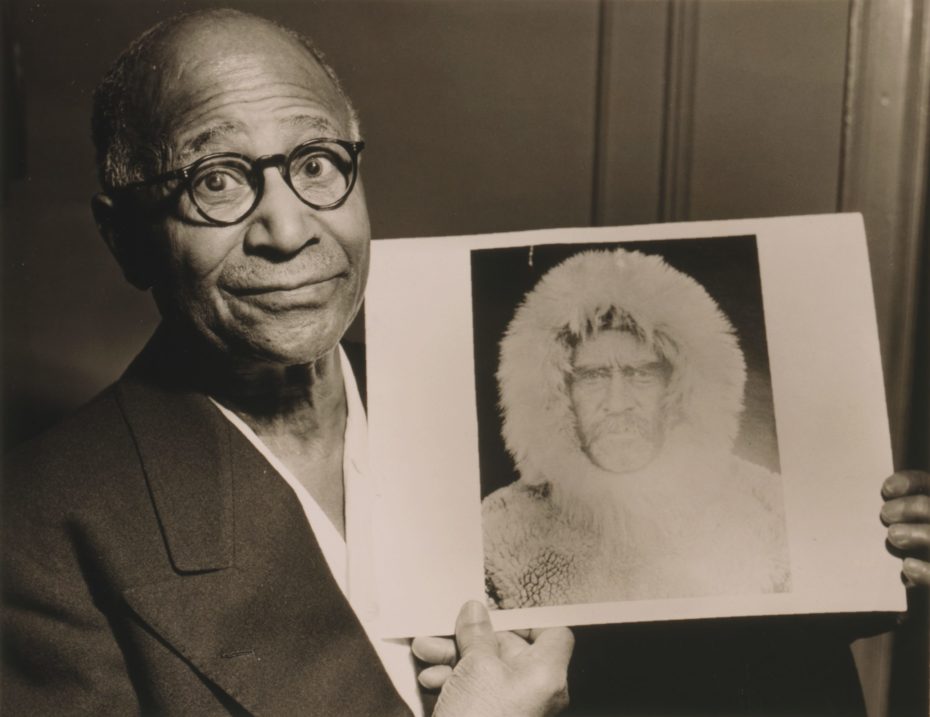

Henson did later gain some recognition in his lifetime, and nearly 30 years after the expedition, in 1937, he became the first African American to be made a life member of The Explorers Club, one of the world’s most pre-eminent societies for trailblazers, with Neil Armstrong and the real life Indiana Jones counted amongst its members. With some irony, in 1944, Henson was awarded the Peary Polar Expedition Medal, which was received at the White House by Truman and Eisenhower.

Henson died in 1955 in the Bronx, NYC, and was transferred to Arlington National Cemetery to be buried beside Robert Peary in the 1980s. He had no children with his wife, but was survived in direct ancestry by an Inuit son, Anauakaq. Both Henson and Peary had children with Inuit women outside of marriage, and in the 1950s, a French explorer spending a year in Greenland was the first to report on their descendants. The explorers had never returned to see their children after 1908, but Henson actually has a great-great-grandaughter in actor Taraji Penda Henson, AKA Cookie Lyon from television’s Empire. It’s a small world after all.

Thanks to an African American Harvard professor, Samuel Allen Counter Jr., making some noise about Henson’s story again in the 1990s, the explorer was posthumously awarded the National Geographic Society’s highest honour, the Hubbard Medal, nearly a century after Peary had been given the same award for their expedition in 1908. African American history has systematically been deprived of its own heroic explorers, but isn’t it about time someone called Hollywood and got Idris Elba in for a screen test?

Read Matthew Henson’s story in his own words, here.