In around 1603, a poet had a decision to make. With a plague underway in England, he could choose to answer to fear, or answer to the muse. Luckily for us, the writer – one Mr. William Shakespeare – decided to put pen to paper (quill to parchment?) and turn out one of his greatest masterpieces, King Lear. “Men must endure,” he wrote while quarantined in his home, in a line that resonates with us more now than ever as we shelter inside, in solidarity with the rest of the world. And y’know what? Bill wasn’t alone in his journey. Sir Isaac Newton – also in quarantine during a long-drawn plague – got busy on a little theory of gravity. That’s the thing about human creativity: there’s no soil in which it can’t bloom. In that vein, there are also many kinds of “quarantine” and “isolation”; physical, mental, societal; collective – from the trenches of war – to that of a singular, cast-bound Frida Kahlo choosing to paint butterflies on her cast instead of despair. As we, too, stay home we look to their stories for strength…

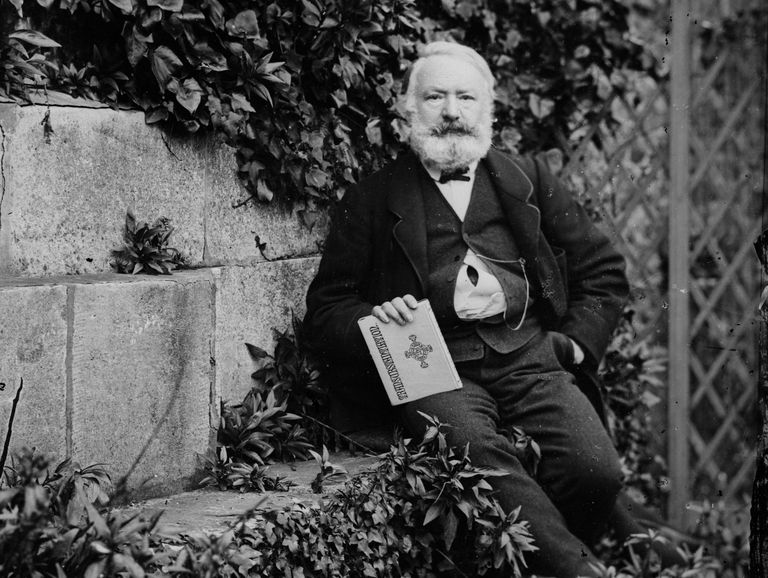

Victor Hugo wrote Les Miserables

French author Victor Hugo was not a fan of Napoleon III – and he went into exile 1851, with full banishment from France, Belgium, and the island of Jersey, before writing some very relatable words: “Exile has not only detached me from France, it has almost detached me from the Earth.” (We feel you, Hugo.) Rather than collapse into his own frustration, he holed up on the island of Guernsey and polished-off a novel he’d been putting on the back-burner for some time: Les Miserables. Touché.

Simone de Beauvoir wrote her first and only play

As a French author famed for her strength of character, Simone de Beauvoir decided to expand her skill-set under under Nazi occupation by writing her first (and only) play, Les Bouches inutiles (translated as “The Useless Mouths” or “Who Shall Die”) in 1945. It’s a poignant story, centred around a 14th century family’s survival during the siege against the Burgundians – and it also represents so much of what creatives were feeling and doing during that time in Paris; Jean-Paul Sartre, who was Beauvoir’s lover and creative partner in many respects, was working beside her to carve out the ethics of Existentialism. In the years to come, this time would be known as her “Moral Period” of writing.

Sir Isaac Newton discovered gravity

Sir Isaac Newton gets a serious gold star for his social distancing skills. In 1665, a young Newton fled the Great Plague of London for a little village about an hour from Cambridge at his family’s estate, Woolsthorpe Manor. Which is cool and all, obviously, but kinda boring – hence why he had time to observe apples falling from trees (so the legend goes) and fine tune his theories on gravity, motion, and even calculus, effectively rewriting the laws of our universe. When he finally got back to the city, it was with a treasure chest of research and knowledge that skyrocketed him to professorship. You go, Newt.

Why not read his biography? Find it here.

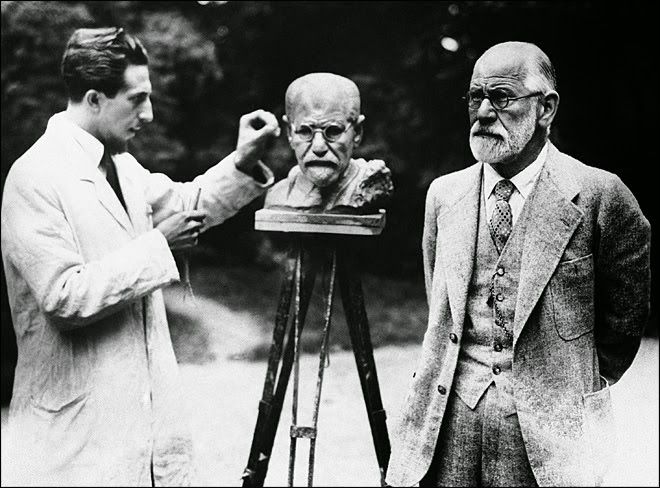

Sigmund Freud wrote his masterpiece

Love him or hate him, you can’t talk psychoanalysis without talking Freud. The man simply never stopped pursuing his passion, even when he was an 82-yr-old on the run from the Nazis and cancer. As a founder of psychoanalysis, Freud was paving the way for the kind of therapy that’s helping a lot of us cope with our emotions right now (ex. free association). He was fled from Austria to London in 1938 where, in the last year of his ailing life, he raced to complete An Outline of Psycho-Analysis. It was published posthumously two years later.

Find a copy here.

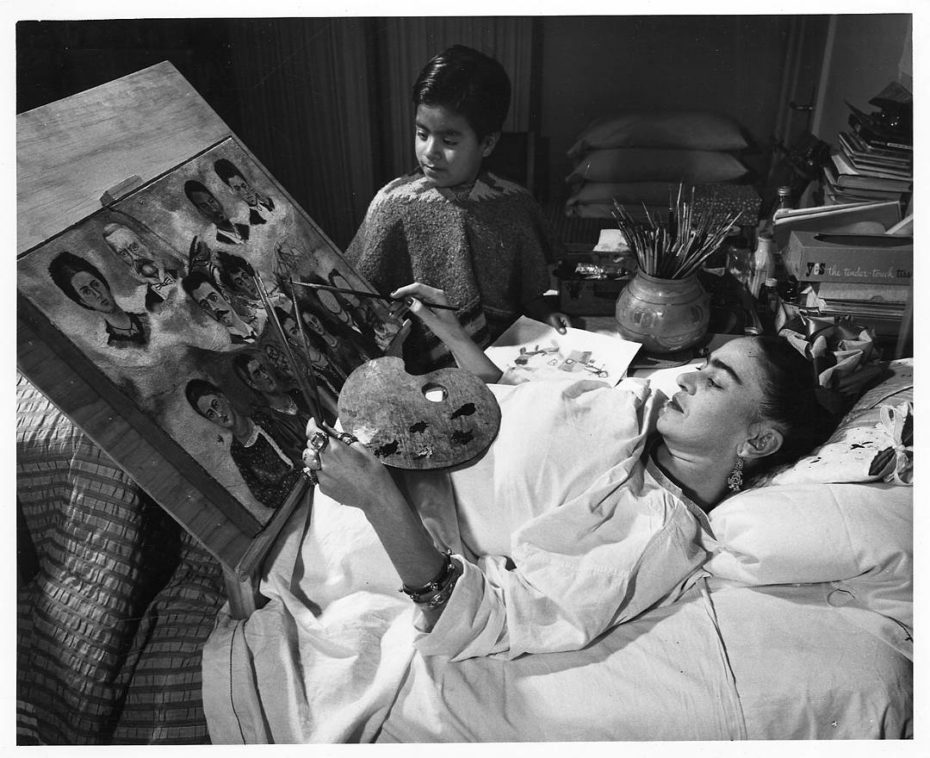

Frida Kahlo made lemonade

273 days. That’s roughly how long Frida Kahlo spent bedridden when she contracted Polio at age six – and that was just the beginning of her very unique relationship with physical pain. Even when the Mexican artist recovered from the disease, she was left with a limp for the rest of her life (eventually, she lost her entire leg to gangrene), and would become seriously bedridden once again as a student, years later, when she was involved in a freak bus accident.

She began painting during her recovery and finished her first self-portrait the following year:

With her body often to weak to support her, Kahlo spent much of her life in and out of body casts. Some days, they felt like a prison. On others, they became her canvas:

It was almost as if Kahlo was predisposed for a life of extremes. But Kahlo met them with a fiery heart, and a passionate hand (how else do you think you get to make out with Josephine Baker, and Leon Trostsky?)

She understood that her pain was real, but that it was also just one part of her life’s perspective. In her words , “Feet, What do I Need You for When I Have Wings to Fly?” To this day, you can see Kahlo’s casts and corsets on view at The Blue House (Casa Azul) in Mexico City.

Learn more about visiting The Blue House here.

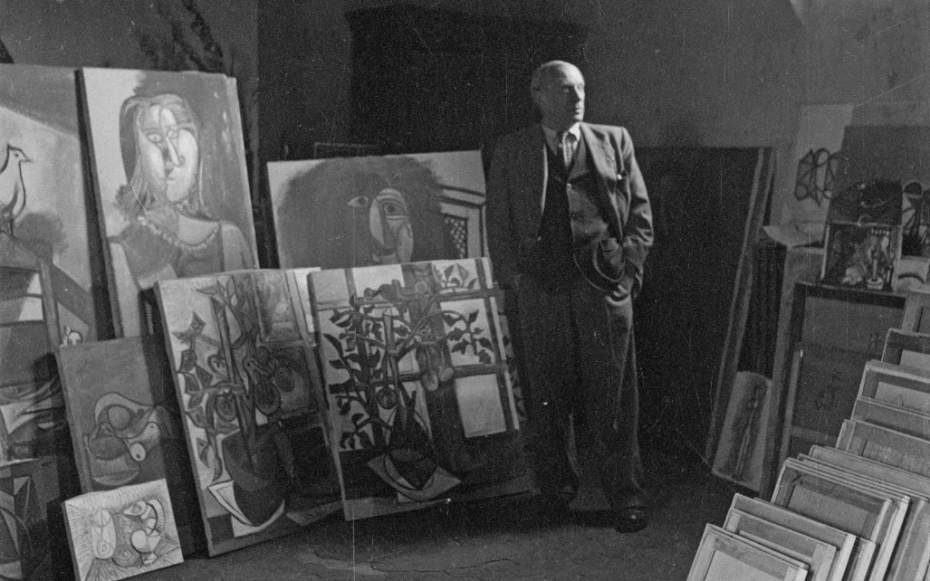

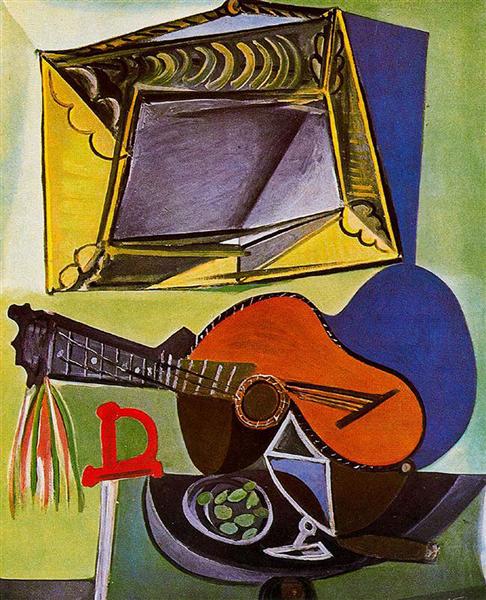

Pablo Picasso made some of his best work

Picasso wasn’t exactly a shy guy when it came to his temperament, but he knew when to lie low. Mostly. Unlike many who escaped Paris during the Nazi occupation, the painter hunkered down and stuck things out in the city, working non-stop. When the gestapo finally searched his studio, he didn’t bite his tongue. “Did you do this?” an officer asked him upon finding a photo of his then famous painting, “Guernica” (1937). The work had already gone down as one of the most iconic, visual war metaphors of our time – a mirror held up to the horrors of what the Germans did to the city of Guernica, Spain. So when the officer asked him if he had done it, he simply replied, “No. You did.”

While Picasso couldn’t exhibit his work during the Occupation, he still made some wonderful works from bronze (smuggled through by his friends in the French Resistance, who he also agreed to hide), hundreds of poems, and wonderful paintings that he would later donate to museums in ravaged places like Warsaw, like Still Life With Guitar (1942):

There are loads of books out on Picasso, of course – but why not check out the National Geographic series where he’s played by Antonio Banderas?!

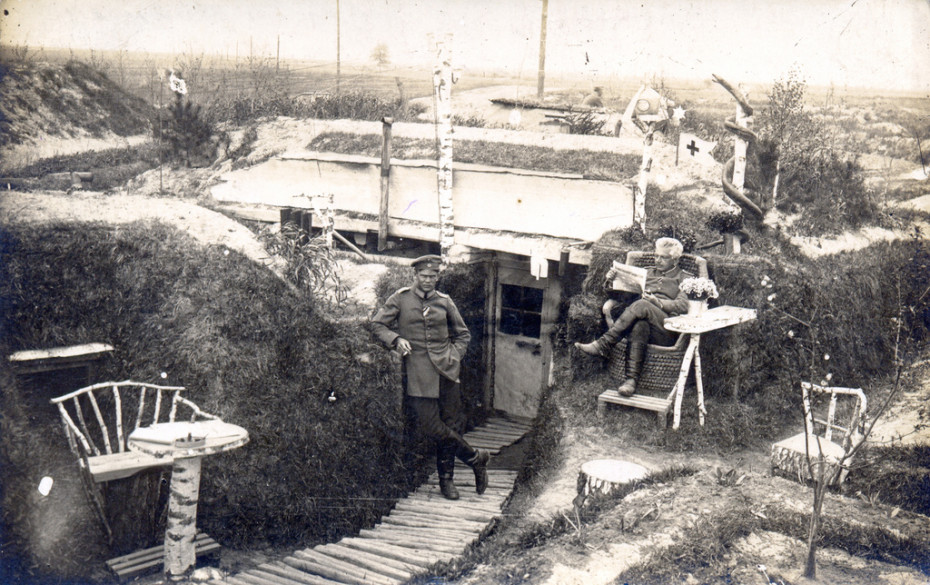

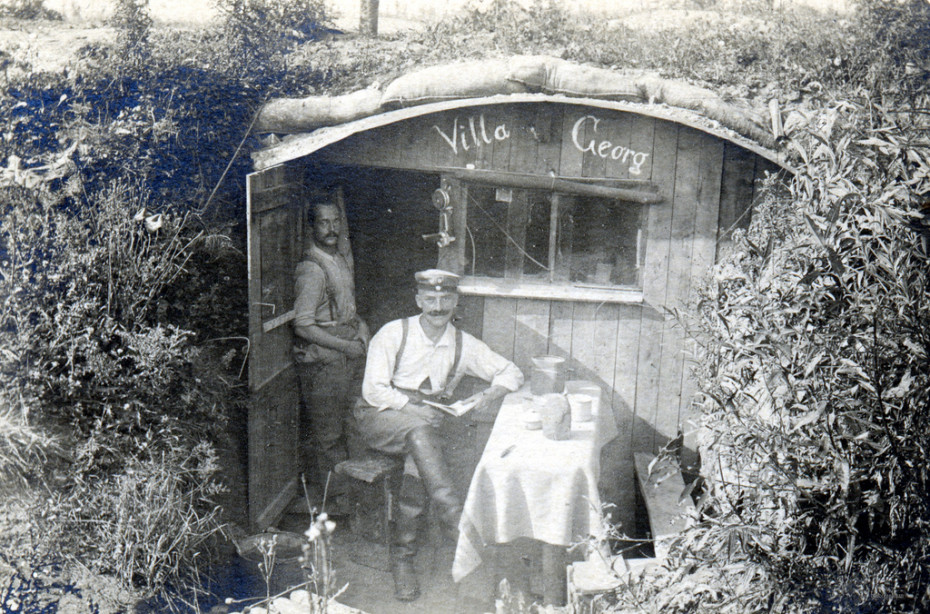

Homemaking in the Trenches of WWI

The question of what we can do in our homes for the next few weeks (we’ve got a whole list for you here) made us think of the art of homemaking in a WWI dugout – which could come in all shapes and sizes, from the elaborate and creative to the most basic, but somehow cozy. Some were several stories deep, almost like small hamlets, while others made do with the little resources they had to make the best of an impossible situation (and certainly puts our own in perspective). It’s the littlest of creative touches that can make all the difference…

See more of these incredible dugouts here.

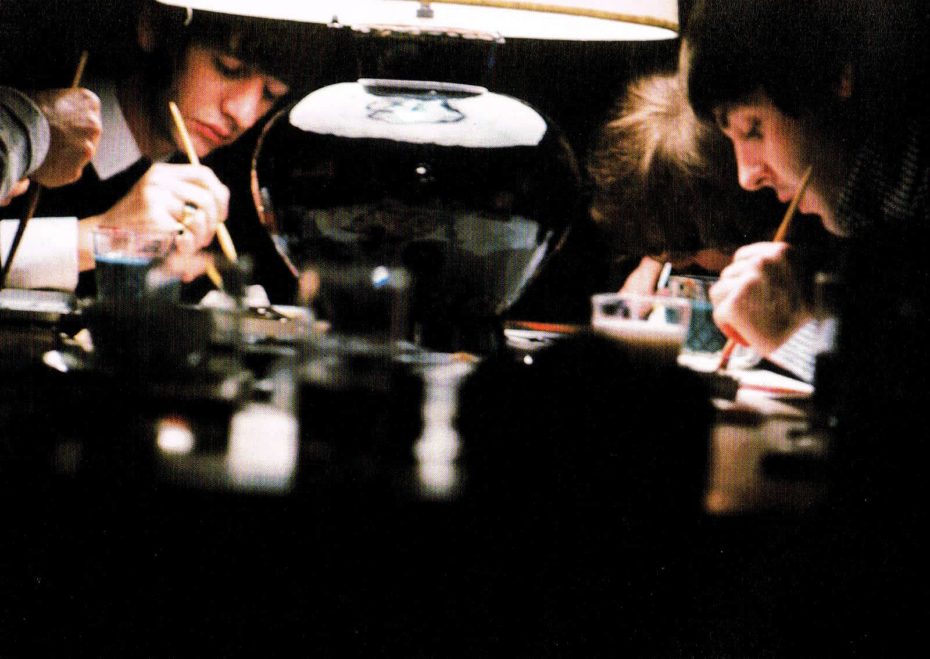

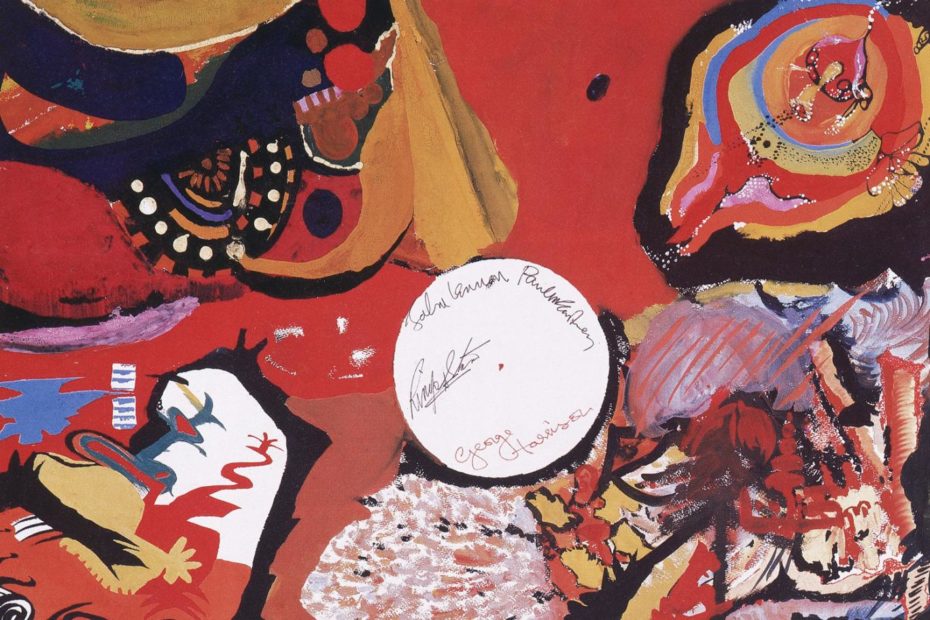

The Beatles made their only collective painting

Images of a Woman, also known as The Tokyo Painting, is an abstract painting by the the Beatles, who had been placed in lockdown as a precaution by the Japanese authorities after death threats had been received:

It is believed to be the only painting produced collaboratively by the group, bought by a Japanese collector in 1989 who stashed it under his bed for 20 years, protecting it from head and humidity in Japan. In September 2012 it was put up for sale through Philip Weiss Auctions in New York and sold for $155,250.

Learn more on Beatles Bible.

Dante wrote his Divine Comedy

Ah, La Divina Commedia. It’s been crowned the greatest single work in Western literature and inspired countless artists, across the ages, from Rodin to Dali; William Blake to a bunch of heavy metal bands. What readers may not know, is that it was born from 20 years of reflection in exile. Author Dantie Alighiera was banned from his beloved Florence in the 1300s for political reasons, and spent the rest of his life wandering Italy and ruminating over What-It-All-Means.

Thus, with Virgil as our guide, Dante’s Divine Comedy takes us on a roller coaster ride through the many layers of Hell. Somehow, it manages to be equal parts frightening and beautiful. In Realms of Exile: Nomadism, Diasporas, and Eastern European Voices, scholar Domnica Radulescu believes this is due to his being so isolated from his everyday reality, wherein his “habits of life, expression, [and] activity in the new environment” feel twice as vivid. Read the timeless work here.

So if they did great things, why the heck not you?