Once upon a time, in pre-revolutionary Paris, French prisoners were set free under the condition that they married prostitutes and emigrated with them to Louisiana. The newlyweds were chained together, escorted to the port and sent to the land of the free. This bizarre and little-known anecdote of history comes from the story of one of the earliest examples of an economic bubble that gave birth to the term, “millionaire“, first coined in 18th century France.

Ever heard of the Mississippi Company or the Mississippi bubble? Maybe you glossed over it in high school history class. The Compagnie du Mississippi was a corporate monopoly founded in France to profit from trade in the French colonies within North America and the West Indies. At the start of the 18th century, France found itself bankrupt no thanks to Louis XIV and his long drawn-out wars, excessive spending and general f*ckery. But the country still owned the Louisiana Territory, which promised to be a “Garden of Eden”, rich in gold, fur and rubies…

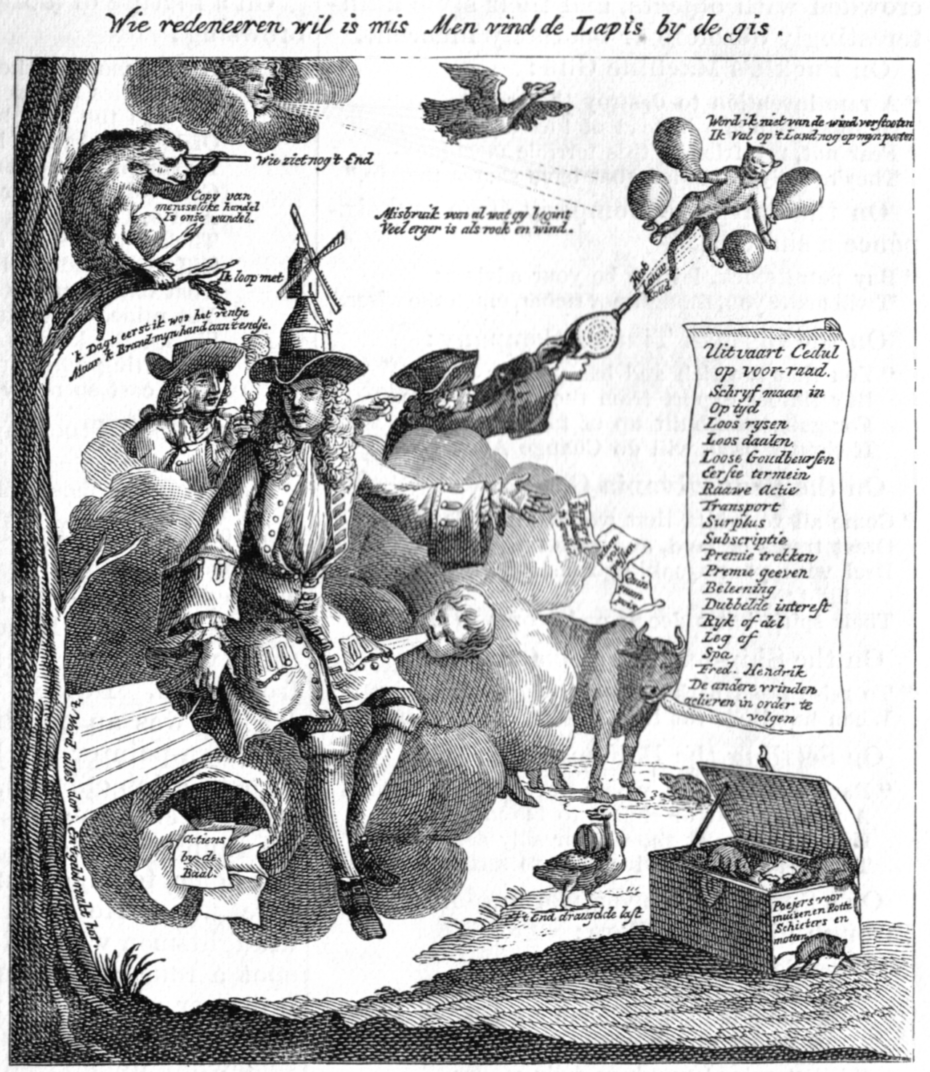

Enter John Law, a passionate economist and mathematician with a gambling problem. Yeah – one of those. So this guy pitches up in Paris and starts hobnobbing with nobility at high stakes gambling parties and becomes chummy with powerful people like the Duke of Orléans, who has just become Regent for the country’s new five year-old king. With Law’s influence and charm, soon enough he convinces French authorities to support a complex plan to create the country’s first central bank with a monopoly on national finance – and the Mississippi Company … to do its dirty work. In order to sell shares in that company, he then sets about convincing the French people that Louisiana is going to make them all rich. And they buy it, quite literally.

Everyone wants a piece in the Mississippi Company, and share prices skyrocket. Meanwhile John Law has the government printing more paper money than there is gold and silver to back it. When shares quickly sell out, the public starts buying shares from each other with paper money. And more of the green stuff gets printed.

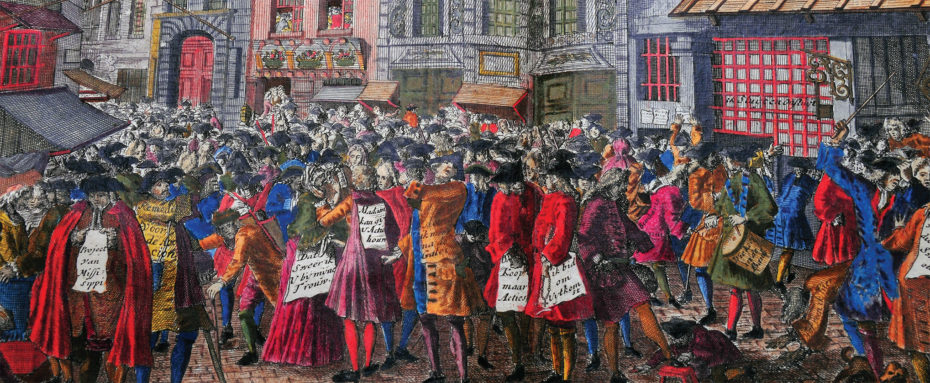

On the Rue Quincampoix, a narrow street in the heart of the Marais not much wider than an alleyway, shares are traded outside of the Mississippi Company’s new offices. This ancient street that has long been a meeting place for moneylenders becomes completely overrun, with traders creating chaos at all hours of the day and night. Some people even earn a handsome wage renting their own backs out as writing desks.

To combat the mania, gates are erected at either end of the block, one entrance built for ‘Speculators of Quality’ (the already-wealthy nobility) and the other for everyone else.

The mayhem on Quincampoix was well-known at the time. Daniel Defoe, author of Robinson Crusoe, stated:

“The inconvenience of the darkest and nastiest street in Paris does not prevent the crowds of people…coming to buy and sell their stocks…up to their ankles in dirt.”

Daniel Defoe

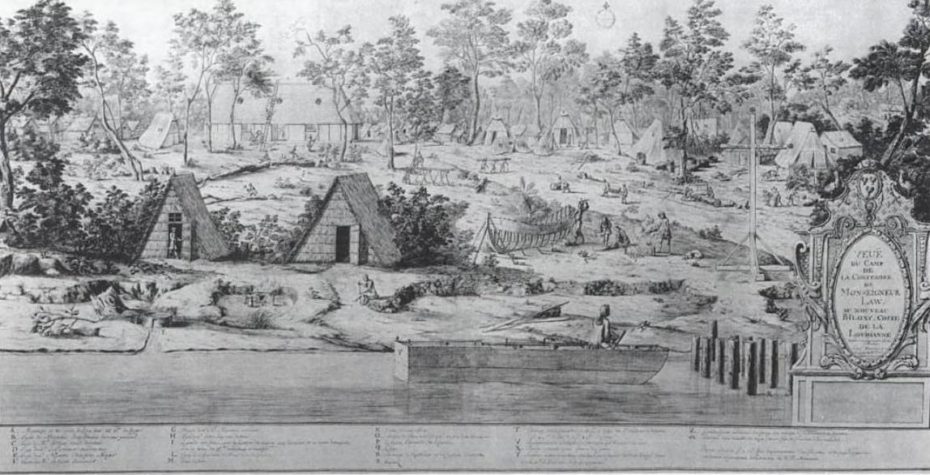

Little do the people know that over in Louisiana, the French colony behind their shares is still a sparsely populated and undeveloped swampland with just 700 European colonists running the show.

The pressure is on to deliver. In order to recruit more people to the colonies to extract what John Law needs from the isolated territory, he begins falsely advertising the “Eldorado” allure of Louisiana. Despite his best efforts, few volunteer to leave the comforts of home and so he turns to society’s “black sheep”. He recruits in hospitals for paupers, prostitutes, drunks and disorderly soldiers. Then he goes to prisons and makes its occupants an offer they can’t refuse: marry a prostitute and set sail into the sunset … to Louisiana.

A honeymoon voyage, it isn’t. Those who accept the bargain for their freedom are shackled together until they board ships on a less-than-first-class voyage to America.

The original colonists of course, aren’t too pleased with the new arrivals and it doesn’t take long before they get out of dodge and move East to New Orleans to distance themselves from the ‘undesirables’ that are invading their camp. Left to their own devices, the criminals, sex workers and black sheep of French society are forced to flee elsewhere too, once starvation kicks in and native Americans figure out this is their chance to regain their territory.

Meanwhile back in Paris, speculators are earning millions of paper notes in a very short space of time, and suddenly there’s a word on everyone’s lips: millionaire! The word would officially make it into the Oxford English Dictionary a century later, noting it as a French term needed because of the “Lilliputian” value of francs. Shade.

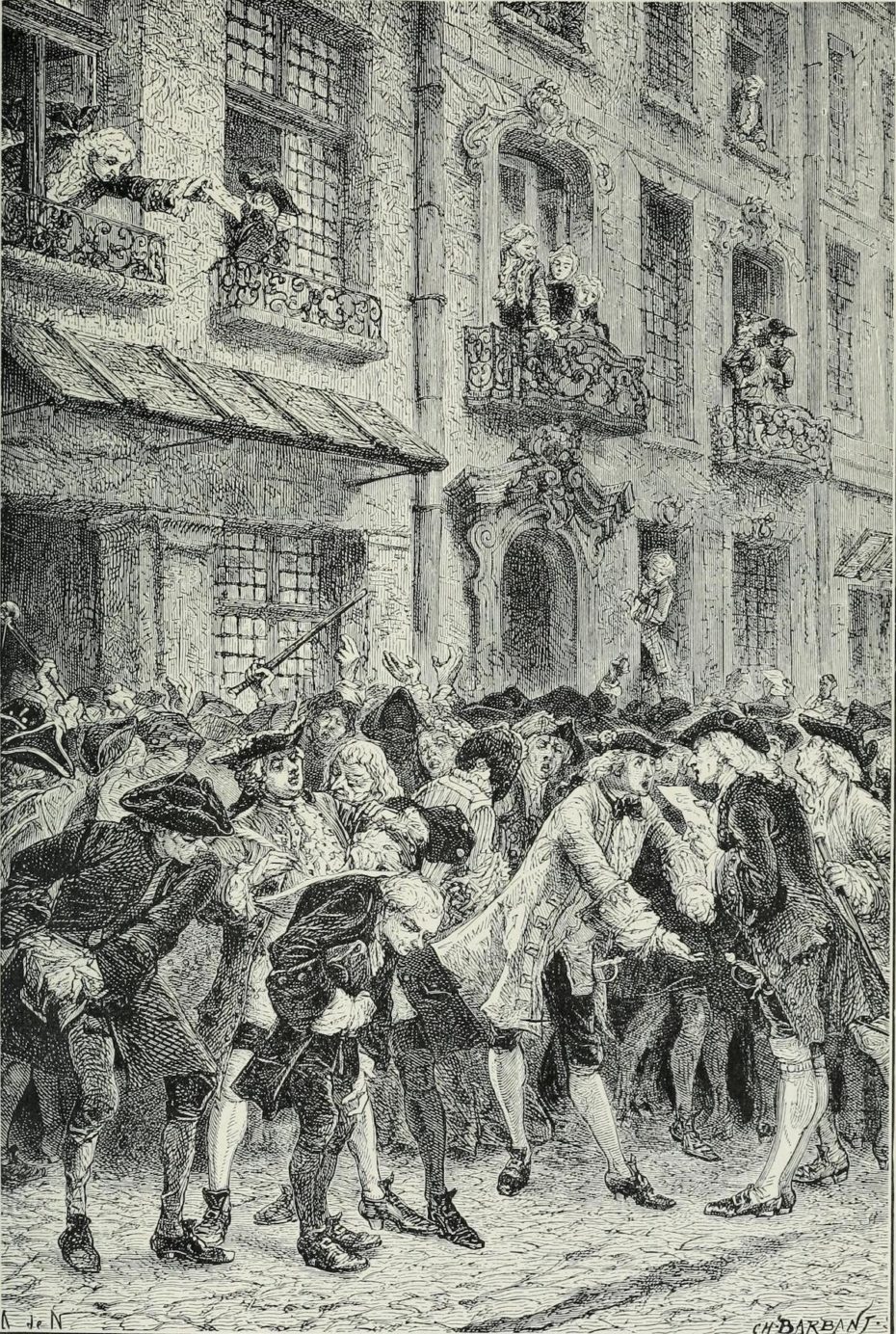

It’s only a matter of weeks before the Mississippi bubble burst at the end of 1720. The rumours had spread that their paper money wasn’t backed by enough gold and silver – in truth, it only accounted for one fifth of the notes in circulation. One well-informed prince figured this out early and managed to cash in first, all but clearing out the bank in Paris in exchange for his paper, making off with three wagons of gold.

Once the word was out, the public scrambled en masse to get their notes converted. To persuade them otherwise, numerous royal edicts were issued to devalue gold. Printing money was declared illegal, as well as selling gold coin. The bank closed. Paper notes became half their face value and turned Paris into a thieves paradise. In short, it was a big ol’ mess. The final straw came when the government did a 180 and declared gold would be legal again, triggering a stampede of people desperate to exchange paper for gold. Seventeen people were crushed to death in a matter of minutes. Outrage set in, and a certain French Revolution would soon be knocking on France’s door.

John Law bore much of the blame for the financial panic and fled Paris disguised as a woman, never to return to France again. He left behind his lavish property on Place Vendôme and at least twenty-one chateaux that he had acquired. He spent his final years gambling in Italy before he died of pneumonia.

One of the earliest examples of an economic bubble, the financial collapse in France caused by the Mississippi Company has been compared to the infamous 17th century “tulip mania” in Holland, considered the first recorded economic bubble in history, when prices for the newly-introduced and fashionable tulip bulbs reached extraordinarily high levels and then dramatically collapsed in 1637.

Oh and by the way, just as the 18th century bubble in France was bursting, across the channel, the South Sea Company of England decided to borrow a few ideas from John Law’s Mississippi Company model, by offering shares in the riches of South America. They call that fine mess, the South Sea bubble.

Moral of the story? We believe the late Notorious BIG said it best when he said: “Mo’ Money, Mo’ Problems”.