The cool thing about being royalty, is you get to go all out on your hobbies. Enjoy miniatures? Not as much as Queen Elizabeth II, whose miniatures collection is truly eye-watering. Into beauty and self-care? Not as much as 17th century France’s King Louis XIV, aka the Sun King, who took his baths in a rare marble basin filled with the eau de parfum of his exotic citrus trees. Which brings us to another one of the Sun King’s extravagant hobbies: ballet. Louis’s passion for dance helped usher the ballet de cour (courtly ballet) into an era with real personality. There was beauty, and humour; style and emotion. There were men – and only men, for a while – in tight, tight tights. It played a huge role in the burgeoning art of ballet not just in France, but the whole of the Western world…

A bit of background: 15th century Italy marked the appearance of the first ever ballets or baletti, and in Louis’s time, it was still for the upper echelons of society to both perform and observe, and took place in the court (hence, ballet de court). But these weren’t anything like the ballets we have today; they didn’t really follow big juicy story narratives. Instead, they’d just have a theme (ex. Springtime, a little national pride propaganda, more Springtime) and lots of pantomiming. Kind of like how you and your friends play charades or karaoke at a party.

But Louis was different. For one, he was his family’s miracle baby – the fruit of his parents’ strenuous efforts, for over two decades, to conceive. He also came to the throne at just 4-years-old. When you grow up thinking you’re the centre of the world, you’re going to adjust your court entertainment accordingly.

So is it any wonder our miracle baby grew up to be such an eccentric? He was a total shoe addict and fashion fiend. He was also a passionate dancer – a habit he picked up from his father. “Louis XIV had great legs,” writes Joan DeJean in The Essence of Style: How the French Invented High Fashion, Fine Food, Chic Cafes, Style, Sophistication, and Glamour, and in fact, he made sure the royal painters highlighted his dancers legs. Louis even “relegated [men’s] boots to the limited place they still occupy today, farming and hunting,” he so preferred a kitten heel to a clunky brogan:

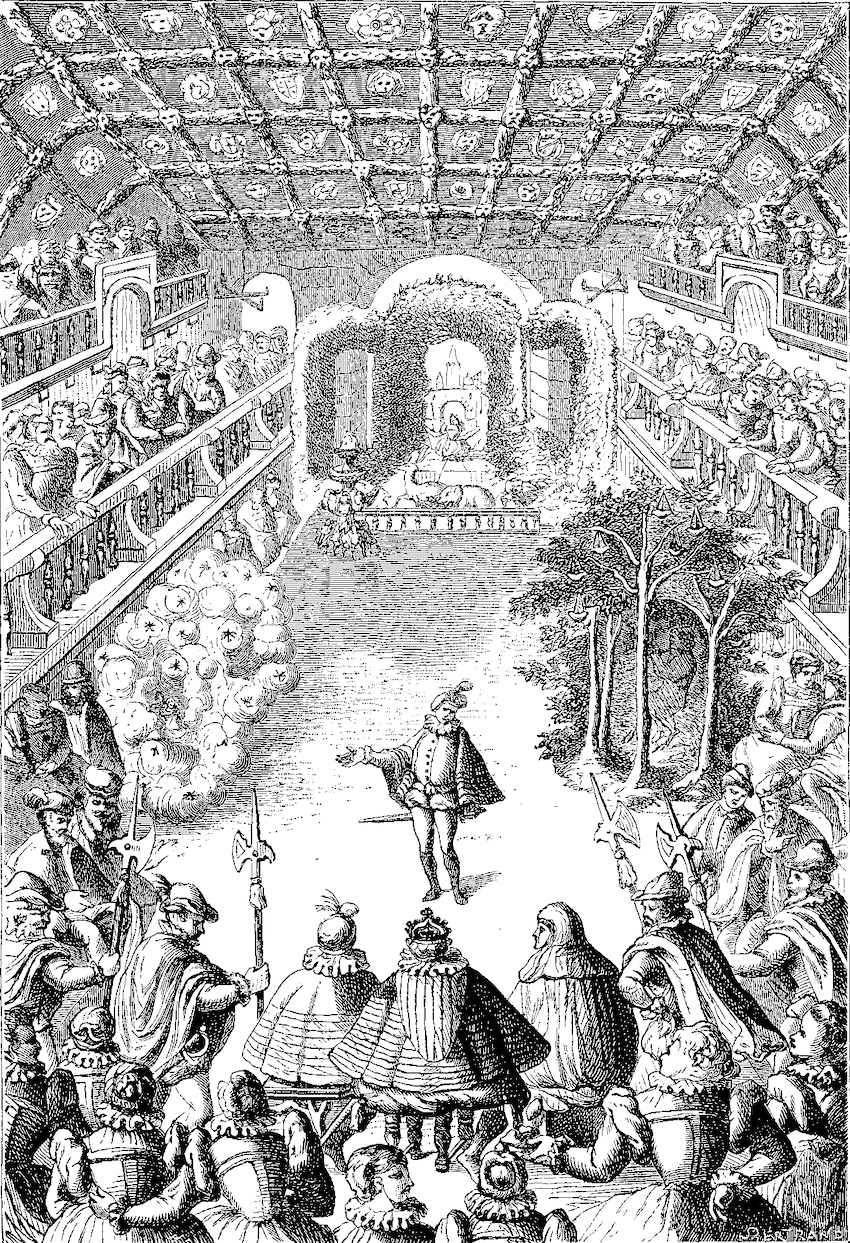

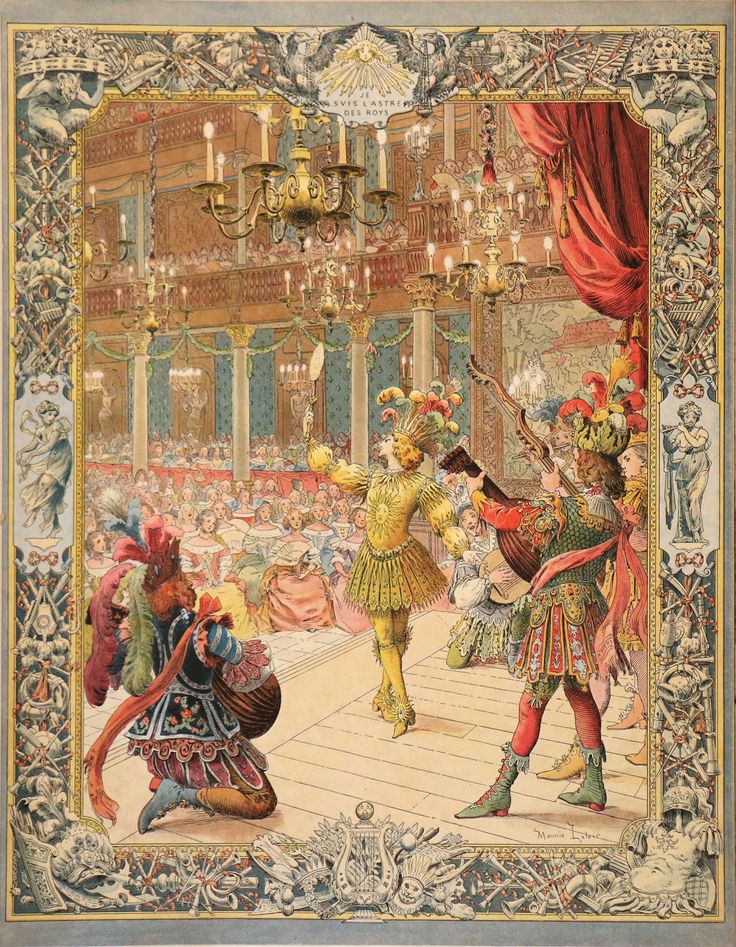

Naturally, his big dance debut was just as fabulous. “He put ballet at the heart of civilised culture,” explains David Bintley, choreographer and director of the Birmingham Royal Ballet, in a BBC documentary on the matter. His breakthrough performance was 1653’s “The Ballet of the Night,” featuring a teenage Louis as (what else) the Sun incarnate.

The glittering performance culminated with Louis’s famously gilded bit, and took place six times at the Theatre du Bourbon. For 12 hours. So you better believe the costumes were good, even if the theme (the sun…rising) wasn’t ostensibly groundbreaking. There was some important political subtext, though, of his role as the maturing king, bringing light to all in his reign, yadda yadda…

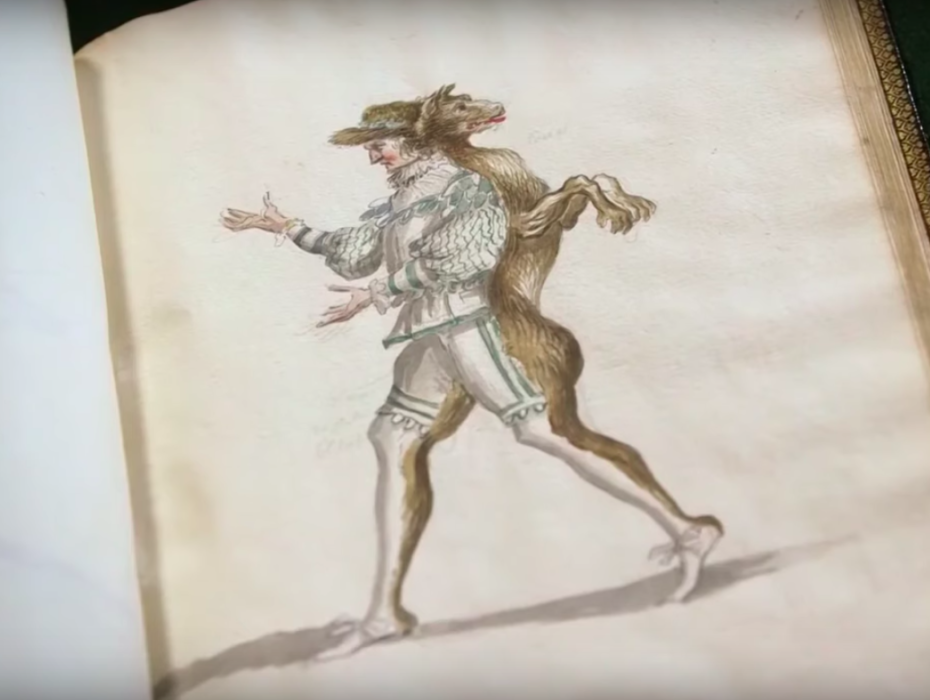

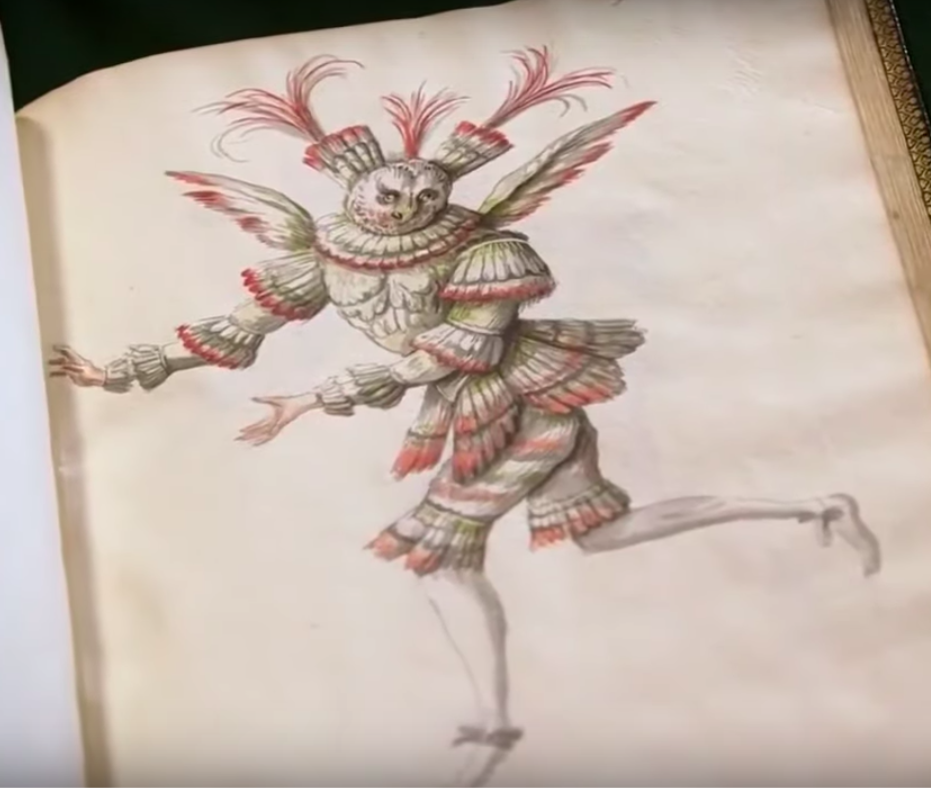

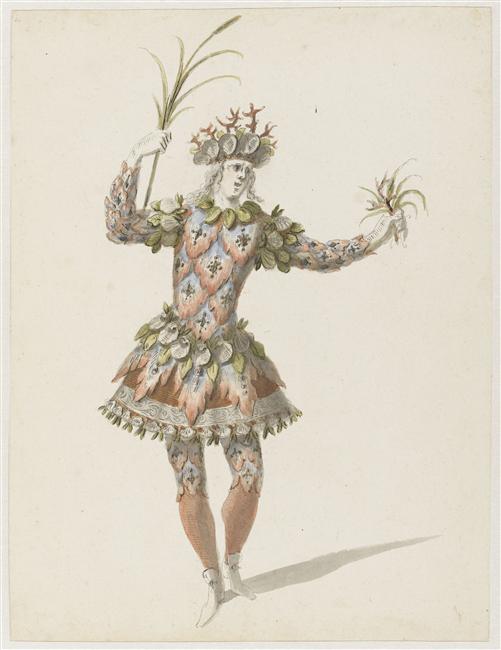

At least there was a lot to look at during those 12-hours. Louis’s taste for the extravagant (and leg-flattering) was beautifully interwoven into the royal costumes, which included tutus galore…

It’s also worth noting that Louis’s breakout ballets were all-male, and included such high cut costumes to maximise dancers’ potential for movement. It wasn’t until later that his courtly ballets allowed women to dance onstage. (For the first. Time. Ever!)

Hence, why we see so many men in tutus: they optimised movement, made for a striking visual, and – of course – showed off the legs of Louis and all of his male dancers.

Paris, musée du Louvre, collection Rothschild

Louis can’t take all the credit, though. His ballets were fuelled by a power trio: the sassy playwright Molière (Tartuffe, Dom Juan), the composer and dancer Jean-Baptiste Lully, and choreographer, dancer and composer Pierre Beauchamp, who gave little Louis dance intense lessons every day for 20 years. Together, they invented our modern concept of the leading male ballet dancer in performances.

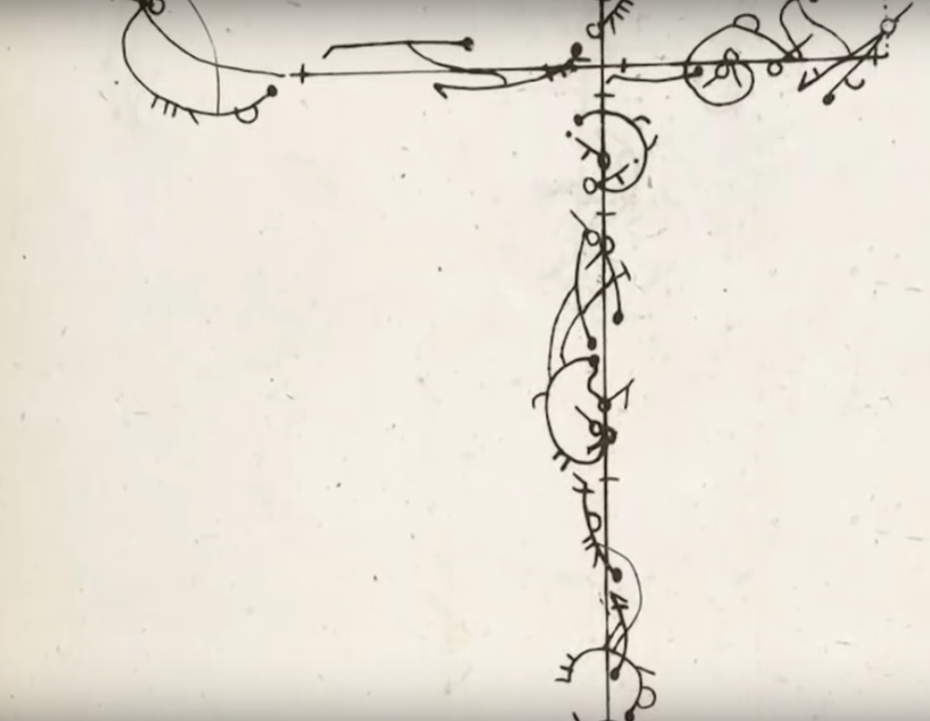

We might add that the dancing was also pretty radical, effectively codifying the five main ballet foot positions we have today. Check out the tangled constellation of Louis’s routine, which represented his mastery of not just a physical routine but esteemed social etiquette. Today, we consider dance as a hobby. In 18th century aristocratic France, it embodied a codified set of social rules that were as important to know as, say, which fork to use at the banquet.

But the best part is how they practiced: with a teeny tiny violin called a pochette (or “pocket” in French) that a dance teacher would play, trailing beside you, whilst you mastered your fancy footwork:

We’re kind of obsessed with them:

With the Molière-Lully-Beauchamp power team, Louis brought ballet as we know it into existence with Les Comédies-Ballets, or “Ballets Comedies.” Not that the implications of a comédie in France were comical. To the contrary, they were rather serious and esteemed (though Molière loved his farce). To this day, Frenchies will raise an eyebrow if you interchangeably use the word for, say, action movie acteurs et actrices (actors and actresses) and comédiens et comédiènnes (more “serious” actors and actresses of the stage variety). Eventually, Louis established the world’s first official royal academy of dance – establishing not only standards for his people, but for the rest of the Western world that endure. Excellence, as they say, à la française.