The saying is we’re ‘living in strange times’, right? But just how “strange” are we willing to admit we’re becoming too? The nature of the worldwide lockdowns has us all looking out of our windows significantly more, searching for something or someone to uplift, inform or entertain us. As we applaud front liners with our neighbours in the city every night, or watch them serenade a block of apartments with a violin aria, we’re being invited into their lives through those warmly-lit windows, just as long as we don’t outstay our welcome. Watching other people’s lives is an inherently human fascination. Some may call it people-watching or human curiosity. Others might call it an invasion of privacy, snooping, spying or stalking. Voyeurism as a general term, will always carry a social taboo overall, but when there’s something interesting to be seen, people tend to cast aside their reservations.

I wanted to dig up some examples of various forms of voyeuristic behaviour and ask some questions along the way. Because something tells me there’s a discussion worth having about the unspoken pastime we’re perhaps all now participating in more than we did before, unwittingly or clandestinely, during these very strange times.

Gail Albert Halaban’s Paris Views

“I really wanted to see the whole city, and the only way to do that was from other people’s apartments,” said Gail Albert Halaban, an American photographer who has made a career taking pictures strangers through their windows. “At first I know it sounds kind of creepy,” Albert Halaban says. “Many people may even think it’s illegal. But I’m a friendly window-watcher.”

She found participants through Facebook, friends of friends, and word of mouth, who all gave permission in advance, and took the project around the world, from New York to Paris and other cities. Reactions toward the nature of the photos were mostly positive, but sometimes not.

Halaban’s work makes the view participate in voyeuristic behavior as subjects seem to be unaware of the camera as they go about their private, domestic lives. So here’s a question: if it’s taboo in real life, is it taboo to be imitated and celebrated in art?

To see more of the photographs from Paris Views, find out more about the photographer here.

Webcams for Windows

The internet of course, is a voyeur’s paradise, with thousands upon thousands of outlets allowing us to survey pretty much the whole entire Earth in real-time. There are the people who willingly set up live cams inside their homes, inviting us to observe their private lives around the clock. Take Drive Me Insane, a family-friendly webcam live streaming since 1997, with one objective: drive the owner insane. The interactive dashboard allows visitors to control various objects in the room, incessantly turn lamps and disco balls on and off, write messages on the computer screen in the background that reads them aloud in a voice synth. When asked if the idea of strangers watching him ever bothers him, owner Paul Mathis says, “Having an inconspicous little camera sitting on top of my monitor looking at me does not present me with an unnerving experience. I don’t sit here dreading all the people in the world who are watching me at this very moment (although I do make some effort to stay fully clothed just in case).”

Still can’t understand what would possess him to do such a thing? Got a public social media account? We expose huge swaths of our lives online, with little thought towards those looking in on where we’re traveling, what we’re eating, who we’re dating, what we’re reading. Are we different?

But back to the webcam world, over in Nevada, the Viva Las Vegas Wedding Chapel has a live cam where you can witness all the inebriated couples making decisions that statistically, they’ll regret in the morning. Whether the participants in the Elvis themed weddings are aware they’re being live-streamed to the internet, is unknown. With the Covid-19 closures, the chapel has gone eerily quiet.

Across the pond in England, you can watch unsuspecting tourists trying to emulate the famous Beatles album cover as they stop traffic at Abbey Road. Again, during the pandemic, tourists are nowhere in sight. But when they return, it’s all just a bit of harmless people-watching anyway – right?

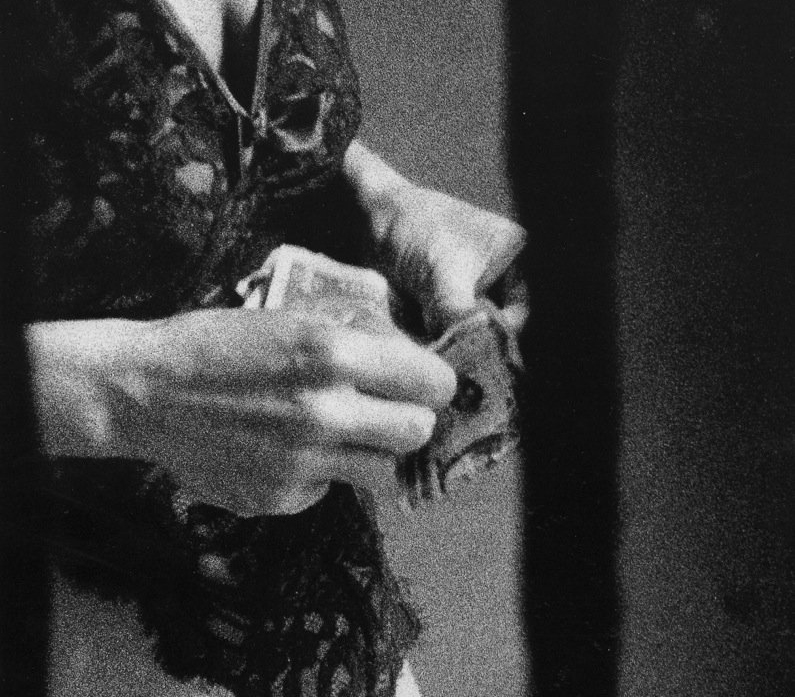

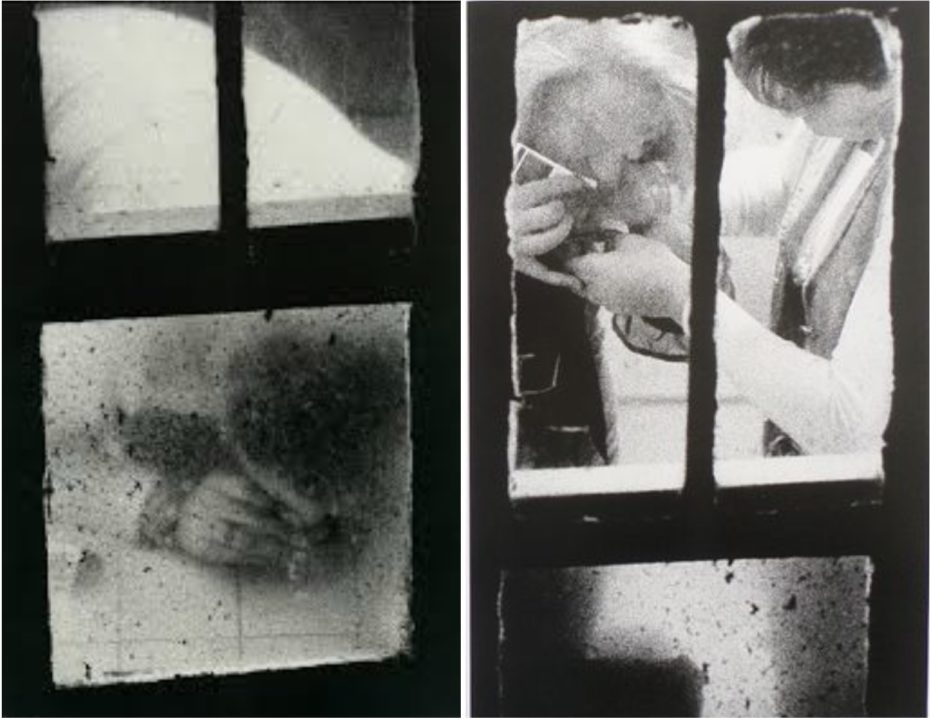

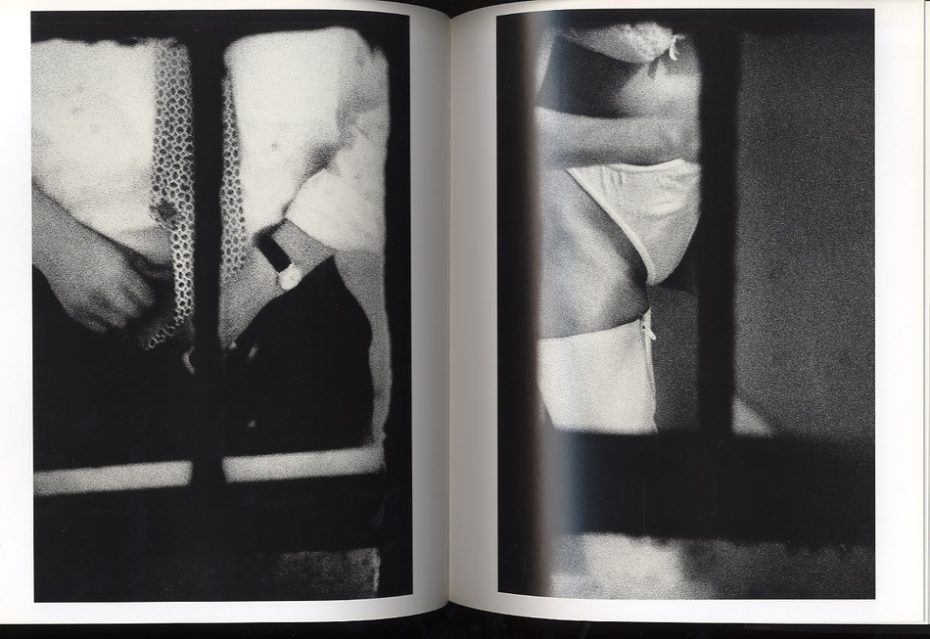

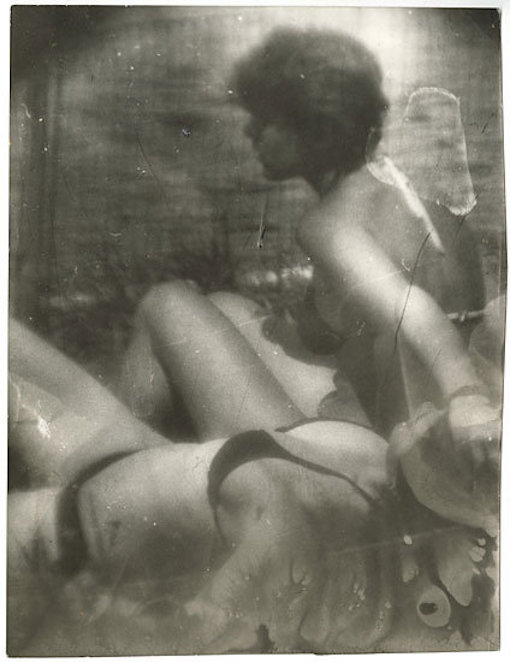

Merry Alpern’s Dirty Windows

Now here’s where things start to get a little more uncomfortable. In 1995, Merry Alpern released her controversial but acclaimed series Dirty Windows, a photo book which contained black & white surveillance photographs of a bathroom window in a private lap-dance club. The suggestive images of men and women engaging in illegal sex, drugs, and in various stages of undress sparked such controversy that even members of US congress used her work in their argument attempting to defund the National Endowment of the Arts.

“Although the notion of the ‘female gaze’ has never really interested me, as a woman I could project some of my own experiences onto the pantomime in the window,” Merry wrote in her book. The club was shut down soon after the book’s release.

Regarded by some major museums as an in-depth exploration of normalization of violence and of male dominance, several of her photos are in the permanent collection at MoMA and the Whitney. One critic compared her work to Degas’:

Using her camera, Merry Alpern manages to convey the suffering and humanity of these women who work to please and who dance naked for a living before the avid male gaze. Just as the painter Edgar Degas portrayed prostitutes and opera dancers, Merry Alpern foregrounds the bleak, behind-the-scenes insecurity of this type of establishment.

As an example of unstaged voyeurism, is it the same as the sort of lurid tabloid content we’re all guilty of lunging for occasionally? Can it be viewed as informative and necessary in revealing the darker side of society? Or is it all the same – an addiction to the rush of voyeurism?

The book is available on Amazon.

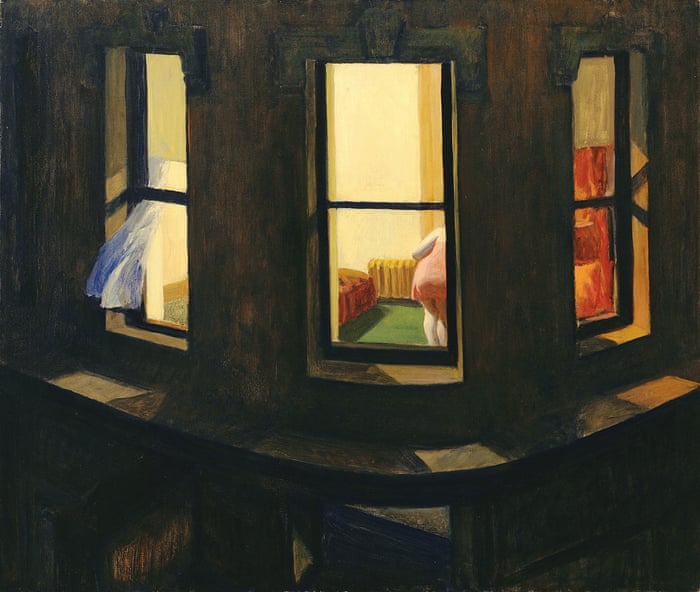

Voyeurism in our Favourite Paintings

Edward Hopper’s voyeuristic perspectives explore the boundary between public and private spaces; inside and outside. And we’re right there with him, watching en masse.

Manet’s most celebrated painting, “Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe” shocked the artistic circles of 19th Century Paris. Where the Impressionist painter Edgar Degas wanted to paint women who did not know they were being watched by the voyeur, hidden by a curtain or through a keyhole, Manet’s central naked figure returns a knowing gaze. The woman in Déjeuner doesn’t seem to mind being looked at. Her pose is casual and untroubled, which is presumably what outraged Parisians who saw the painting 150 years ago, when the rise in the number of prostitutes in Paris and their ubiquitous presence increasingly concerned the bourgeoisie that society was being undermined from within.

With Manet’s oeuvre, the spotlight is suddenly on the unseen viewer and they are being confronted with the moral question of their presence as a voyeur or consumer of such imagery. Manet considered himself to be a Realist artist rather than an Impressionist. That’s the thing about Manet. Was he just getting “real” and trying to tell us that we are all voyeurs? Something tells me he wanted us to talk about it.

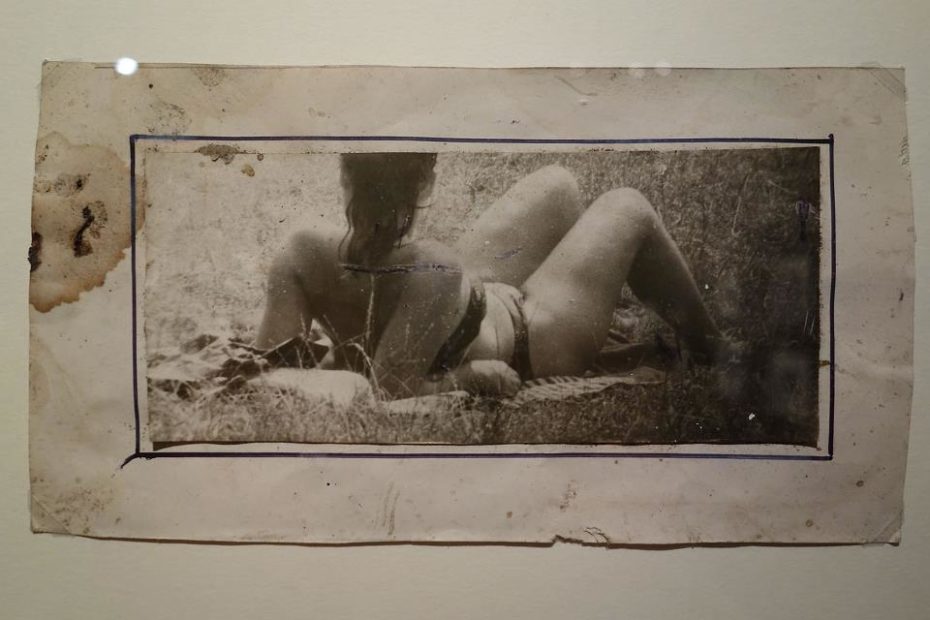

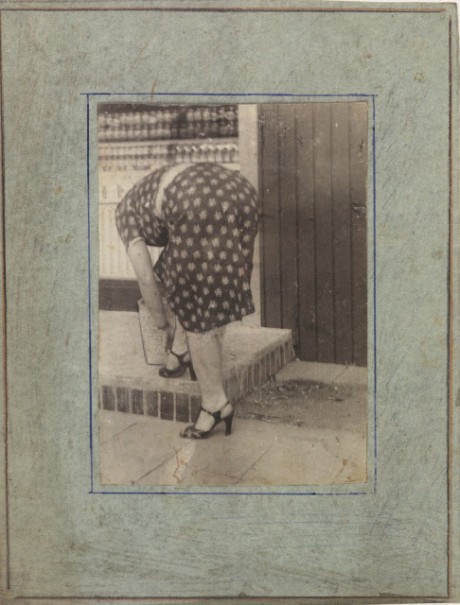

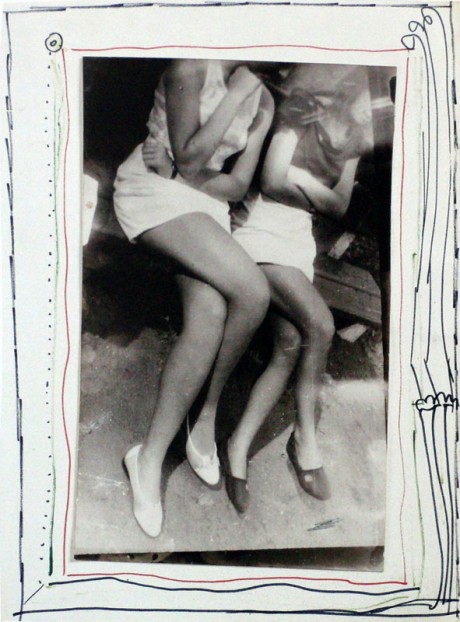

A Reclusive ‘Peeping Tom’ Photographer and his Street Voyeurism

The townspeople of Kyjov in Czech Republic could never quite decide. Miroslav Tichý took nearly a hundred photographs a day with his homemade camera, wandering around the streets of his hometown, often spotted at bus stops, the main square, the park and the swimming pool, although he was frequently arrested for lingering around the local pool taking pictures of unsuspecting women.

For more than twenty years, his work would remain secret until a childhood friend and neighbour discovered his prints amongst the chaos of undeveloped rolls and cardboard cameras. His work has since been celebrated at museums and galleries across the world including London, Paris and New York.

In 2004, Buxbaum’s collection of his photographs was shown at the Biennial of Contemporary Art in Seville and the following year, the works won the Rencontres d’Arles 2005 New Discovery Award. Then came major retrospectives of his work, celebrated for its poetic imperfections, in Zurich and Paris.

Since his discovery, Tichý never once attended an exhibition and remained an outsider for the rest of his life. The voyeur is in every photographer, and essential for being able to see others. The question is, at what point does the street photographer become a lurking boogyman with a camera?

Learn more about Tichý and his work here.

Voyeur, a Netflix documentary

Journalism icon Gay Talese reports on Gerald Foos, the owner of a Colorado motel, who spent two decades secretly watching his guests with the aid of specially designed ceiling vents, peering down from an “observation platform” he built in the motel’s attic. This one leaves little doubt as to where voyeuristic behaviour crosses the line, but it’s takes a good look at issues of journalistic ethics intertwined with a compelling insight into the mind of a real-life Hitchcock’s character.

Hitchcock’s Rear window

Alfred Hitchcock praised the curious nature of human voyeurism. It’s a recurring theme in many of his films, but none are more relevant today than Rear Window. The character of Stella played by Thelma Ritter calls us “a race of peeping toms.” The audience participates in voyeuristic behaviour as the main character played by James Stewart watches his neighbours across the street during his wheelchair-bound confinement. Rather than revelling in his audience’s guilt for joining in, perhaps Hitchcock was trying to tell us something….

John Fawell, a humanities professor at Boston University and author of Hitchcock’s Rear Window: The Well Made Film, writes:

“[Voyeurism] has its healthy implications. It is through his peeping that Jeff solves Mrs. Thorwald’s murder (no one else seems to care) and also gains a more human quality, a greater sense of other people’s vulnerability … We are not likely to leave the film with a sense of having spent two hours in salacious voyeurism. Rather, our glimpses into other people’s lives in Rear Window tend to leave us feeling more aware of the way in which people suffer in close proximity to one another, more sensitive to the sights and sounds of loneliness in our own world.”

So now that the world has slowed down, and we aren’t all going about our busy lives with little regard for those around us, are we suddenly able to take a look at the realities we weren’t able to see before? The loneliness of a neighbour? Homeless people that have nowhere isolate and who aren’t so invisible now on our empty streets?

MessyNessyChic’s own Style Spy

If you follow MessyNessyChic on Instagram, you’ll probably have stumbled upon a series I came to name as “Style Spy“, which to my bemusement, has probably become the most watched form of content on that social media platform. In hindsight, it can be argued that Instagram owes its success almost entirely to voyeurism, but that’s a whole other can of worms isn’t it.

It began two years ago when I captured some elegantly dressed Parisians from my balcony attending the local market one Saturday morning. Viewers seemed to enjoy it, a lot, and asked for more glimpses of my market square. It became less about “spying” for Parisian style and more about finding little everyday moments captured from above that made me smile. The reality is, these moments are not staged and I don’t have anyone’s permission. I gain no pleasure in observing others without their knowledge, although I have less interest in capturing staged moments.

So do I ever think I should quit doing it? The short answer is, sometimes. The long answer is this: I draw a clear line between sharing voyeuristic material that sets its gaze on the public sphere vs the private sphere. I strive to share feel-good moments of positivity over negativity above all – but can I be sure that everyone will understand or agree with that? Unlikely.

On several occasions, I’ve been contacted by the people I capture on camera (a small world indeed), but rather than being met with the reproach I feared, the reactions so far have been peculiarly positive, if not the most memorable interactions I’ve had on social media. Does that give me validation? Again, that’s a no.

It’s a risk that I take and grapple with in going public with my voyeuristic form of documenting the streets and people of Paris. It’s the risk we all take when we take out our cameras in a public space or share something on social media.

Because of the nature of the material and MessyNessyChic’s content in general, I still feel that I can trust my audience and community with it and in the process, begin to better understand an inherently human fascination with watching other people’s lives. I relate to the idea that glimpsing into other people’s lives can leave us feeling more aware and sensitive to strangers and those around us. I hope that the audience is moved, inspired or uplifted by them, as with all our content, and that faith in humanity, as they say, can be restored, even just for a moment. I believe we have a psychological need to find common elements, to bond and to see ourselves in others, especially in times like these.

And maybe that’s naïve thinking in a world where we have little control beyond our own windows of morality. And maybe I’m mistaken in feeling like I can still treat this platform like my personal “bedroom blog” that only my closest friends would tune into. But hey, at least I’ve provided a good conversation starter for the dinner table (or video chat) tonight. There’s a lot to discuss.