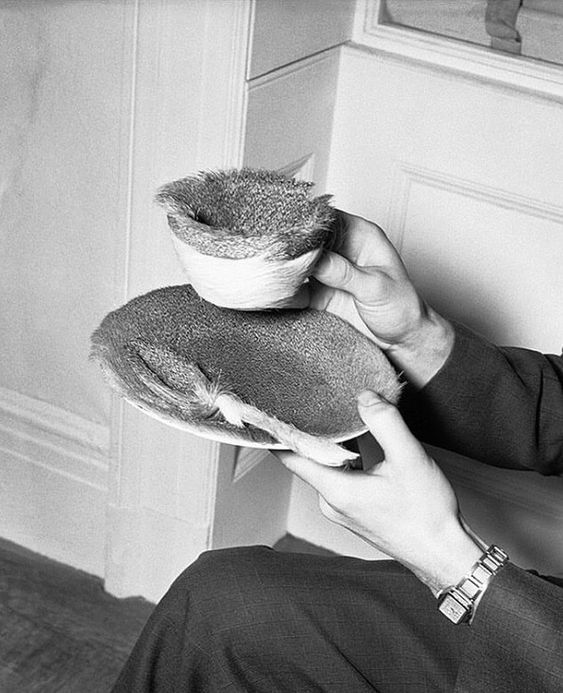

She became famous overnight with a strange furry teacup that mesmerised the art world in a way that no woman had done before. In a time before shock-seeking art became the norm, Meret Oppenheim was a pioneer; a force of nature who had all the Surrealists of Paris speaking her name, even though she didn’t quite fit into their boys club, nor could she be considered an established artist at just 23 years-old. But this sudden fame led to at least two decades of self-imposed isolation in her home in Switzerland to escape and redefine her newly established identity. History seems to have forgotten the rest of her work, much of which was overshadowed by the Objet. She wrote countless poems, a posthumously published screenplay, and she worked in an array of mediums, from watercolour and oil paints, to bronze and collage. She even collaborated with Coco Chanel’s greatest rival, Elsa Schiaparelli, and designed costumes for Picasso’s play Desire Caught by the Tail in 1956. Today, while Dali, Magritte and Max Ernst are household names, Oppenheim remains little-known amongst the forgotten women of the Surrealist Movement.

Meret was born in Berlin in 1913. She was named after Meretle, the child in Gottfried Keller’s 1855 novel who lived freely in the woods. The First World War broke out before she could walk, and her father was called away to serve as a doctor. Her mother took Meret and her two siblings to live with her grandparents in the “Villa Solitude” in the Jura Mountains in Switzerland. Gran was a suffragette, famous for her children’s illustrations. The home was frequented by all kinds of bohemians and intellects, including Hugo Ball, the Dadaist who wrote and debuted the Dada manifesto at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. Her aunt, Ruth Wenger, also lived a categorically modernist lifestyle, and she was briefly married to Herman Hesse whose novel, Siddhartha, became one of the greatest inspirations for the hippie generation of the 60s. It’s safe to say that Meret was in good company.

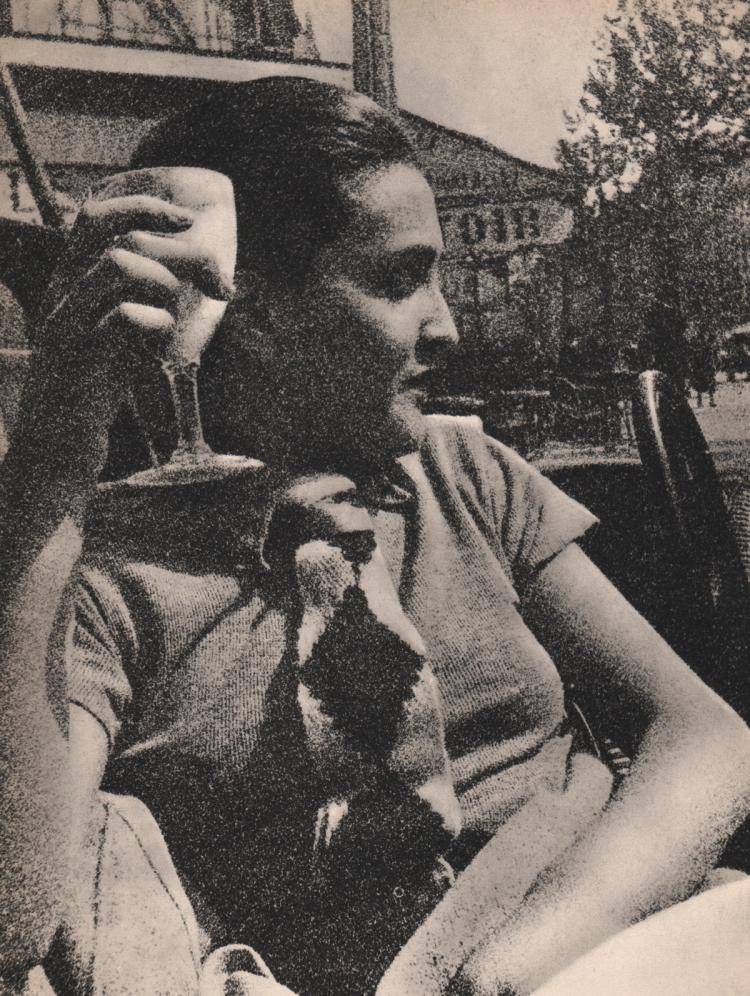

By the age of 18, she already knew she was going to be an artist, and took off to Paris to master her skills. Her adventures began once she got on the train with her friend and fellow artist, Irène Zurkinden.

“On the train, the two young women drank enough Pernod to be feeling cheerfully lightheaded by the time they reached Paris. There, “without [even] washing their hands,” they went straight to the Café du Dôme, where all the artists congregated in those days”

Bice Curiger

Oppenheim studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière where Picasso, Delacroix, Manet and Cézanne painted (the school still exists offering walk-in classes) and set up her studio on the Left Bank in the Hotel Montparnasse. She arrived with an unflinching sense of self, rebellion and free spirit. The Surrealists had never met anyone like her and she quickly became the youngest member of the male-dominated group.

She would attend Surrealist meetings with André Breton, Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia and Max Ernst, with whom she ended an intense romantic relationship in fear that it would overshadow her own work.

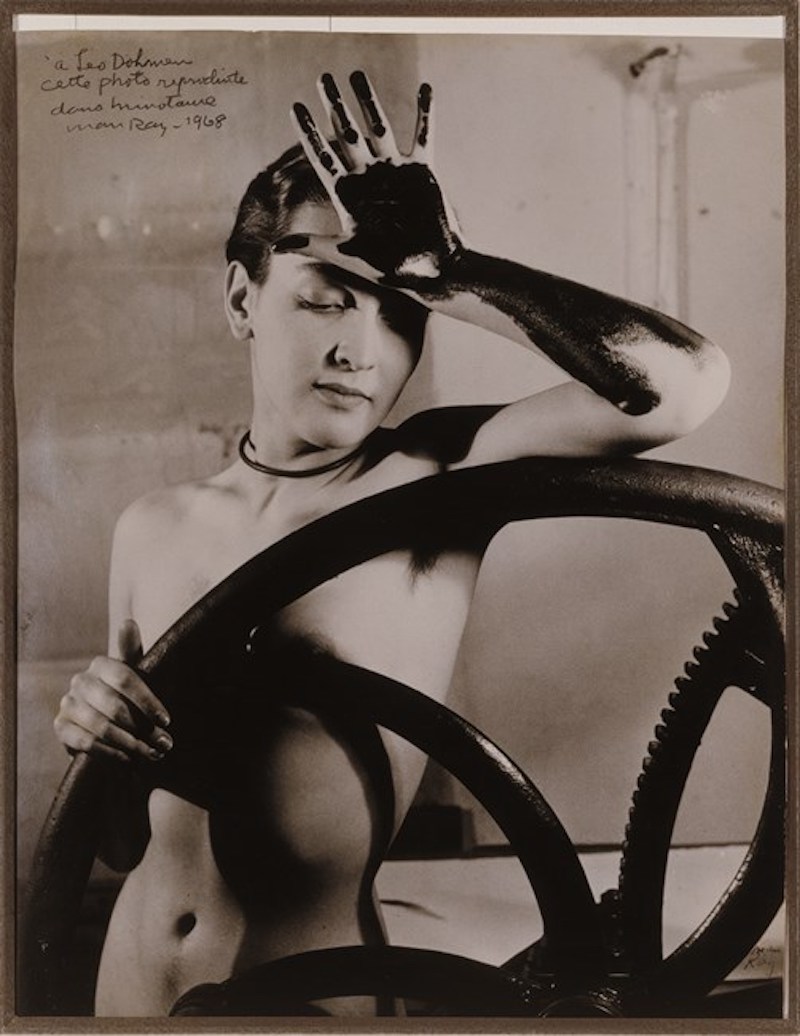

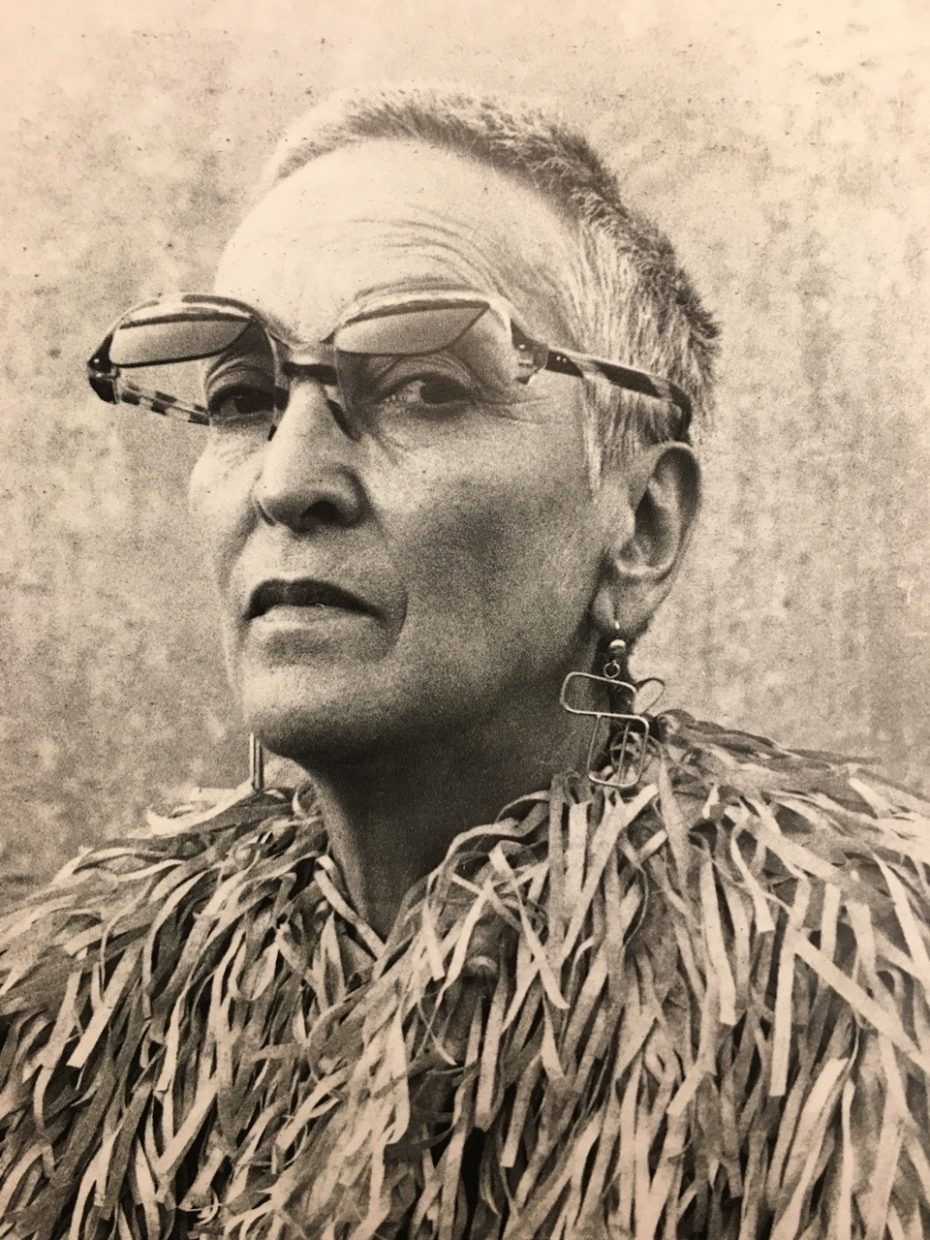

Man Ray was particularly inspired by the artist, and said she was “one of the most uninhibited women I have ever met”. He went on to study and admire her through the photos he took. The most iconic photo taken by Man Ray is the Erotique Voilée where she posed so gracefully against the printing press, with her short androgynous hairstyle slicked back behind her ears, and her artfully ink-stained hand and arm held up on display.

She was “the quintessential embodiment of the Surrealists’ ideal muse”, said Art Historian, Mara Wit, while another Art Historian, Josef Helfenstein, remarked that it was “her beauty, her youth, her rebellious attitude” that the Surrealists first and foremost responded to.

It was against this backdrop that Objet, otherwise known as, Breakfast in Fur (Dejeuner en fourrure) was conceived. The story goes that she was inspired to create it at a meeting with Pablo Picasso and Dora Maar at Les Deux Magots café on Boulevard Saint Germain, after Oppenheim’s fur bracelet got the conversation started.

Ah, said Picasso, you know, you could cover almost anything in fur. And Meret, never at a loss, replied: “Even this cup and saucer.” So she did, and when in 1936 André Breton asked her to make something for the first Surrealist exhibition devoted to objects, she went out and got a teacup and saucer and spoon and attached the fur of a Chinese gazelle to them.

Mary Ann Caws

To create the name Breakfast in Fur, it was André Breton who mish-mashed the title of Sacher-Masoch’s novella Venus in Furs (which also inspired the famous Velvet Undeground song) and the title of Manet’s painting Dejeuner sur l’herbe. Meret point‐blank rejected of the sexy nickname of her work.

He did it again with her boots joined at the toe, which she named, “The Couple” in 1956. When she submitted it to Breton for an exhibition, he renamed the work, “The Undressing”.

While she had been admitted to the Surrealist’s club, she was no doubt up against a constant battle of the sexes.

The furry tea set was exhibited in Paris, London, and then in 1936, it went on show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York as part of the “Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism” exhibition. Alfred Barr, the director of the museum at the time, and the very first director of the museum in fact, decided to purchase Oppenheim’s work, making it the first Surrealist work of the whole collection.

“Few works of art in recent years have so captured the popular imagination…. The ‘fur-lined tea set’ makes concretely real the most extreme, the most bizarre improbability. The tension and excitement caused by this object in the minds of tens of thousands of Americans have been expressed in rage, laughter, disgust or delight.”

Alfred Barr

Barr, however, kept it away for study because he thought it was too radical to exhibit at first. You have to imagine a world where we haven’t already been de-sensitised by contemporary art. It was all so new and shocking to see everyday objects “twisted” in such a surreal fashion. Despite the controversy, Dejeneur en fourrure became an overnight sensation and Oppenheim escalated to heights of success she couldn’t have imagined. For many artists, this would appear to be a blessing, however, for Oppenheim, this led to an existential crisis. Even to this day, she has become defined by the work, and she spent the rest of her life trying to emancipate herself from the trap that this success had closed in on her.

“It must be unbalancing to have an unexpected event in our life rob us of our identity, forcing us to live with a false replacement, a label to make us question who we are and redefine us in the eyes of others.”

Salomon Grimberg, 2014

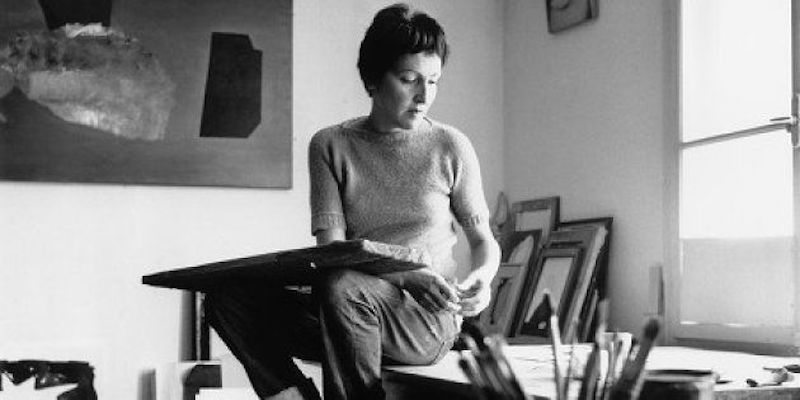

Trying to come to terms with her celebrity, she returned to Switzerland and fell into a depression, and sadly destroyed much of the work she produced. But even though Oppenheim’s image became defined by her Objet, she never ceased to experiment and develop her extensive and eclectic artistic repertoire.

One of the first decisions she took when she got back home, was to enrol in the School of Commercial Arts in Basle, where she studied traditional subjects like perspective, colour and portraiture. A few years later she also took up restoration work.

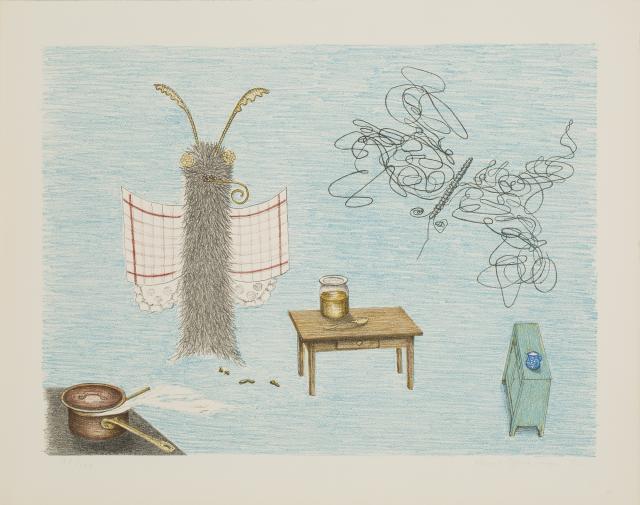

Meret created many fantastical objects which played with ideas of opposites, such as her Sugar Ring, where ephemeral sugar crystals were put in place of a precious, everlasting stone, on a ring plated with gold.

She was also invited to work with Elsa Schapirelli, who included the fur bracelet in her winter collection. Their joint piece de resistance however, was their collection of gloves.

” Featuring eerie trompe l’oeil details such as fake fingernails and painted veins, Oppenheim showed how a unique, artistic concept could have an impact on the world of fashion. She also designed a pair of shoes with faux toes—a design detail that has reemerged on the runway from brands like Celine and Comme des Garçons.”

Aria Darcella and Benjamin Galopin

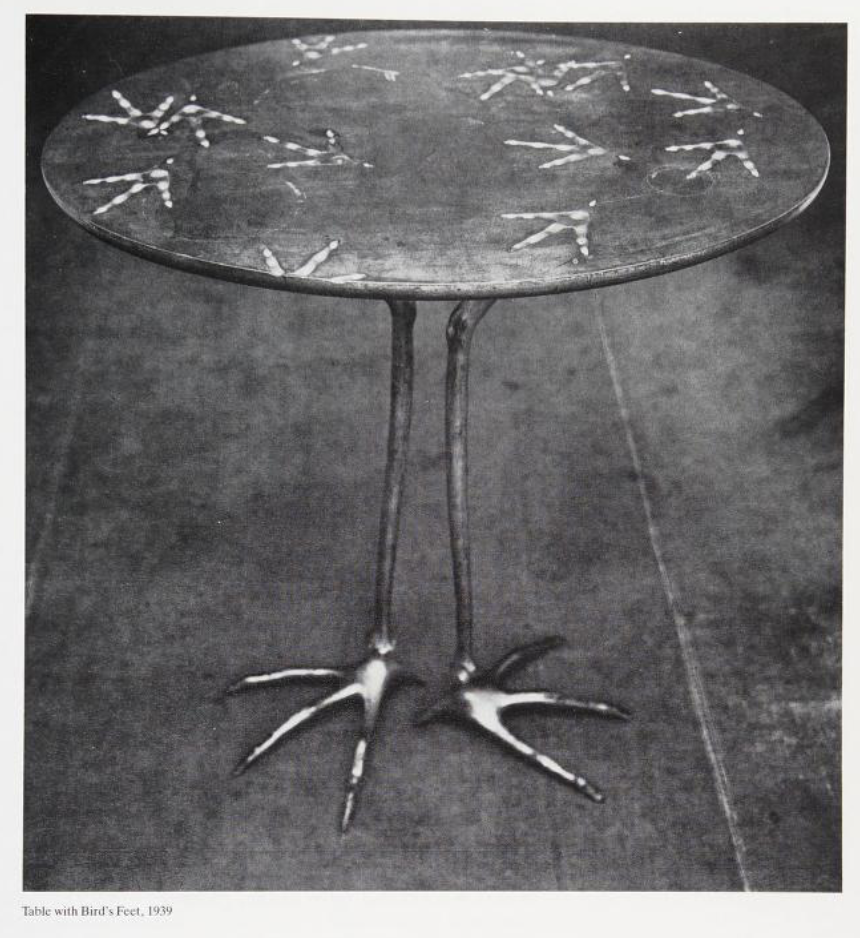

There was furniture too. Meret’s whimsical Table with Bird’s Feet held up by birds legs which was on display at a fantasy furniture exhibition at the Place Vendôme in 1939 in Paris, was praised by the leaders of Italian design in Milan during the 70s, and has now become an object of stylish interior design that most recently featured in Architectural Digest.

She was a forerunner in performance art with her Spring Banquet (also known as “Cannibal Feast”) in 1959, where she invited three couples to a playful feast that was served on the body of a nude woman.

When Breton heard about it, he asked her to re-create it to open the last International Surrealist Exhibition, although she was angry when her work was misunderstood as an objectification of women. The work was first and foremost meant to represent fertility; mother nature and the abundance of her creations; and the cycles of life and death.

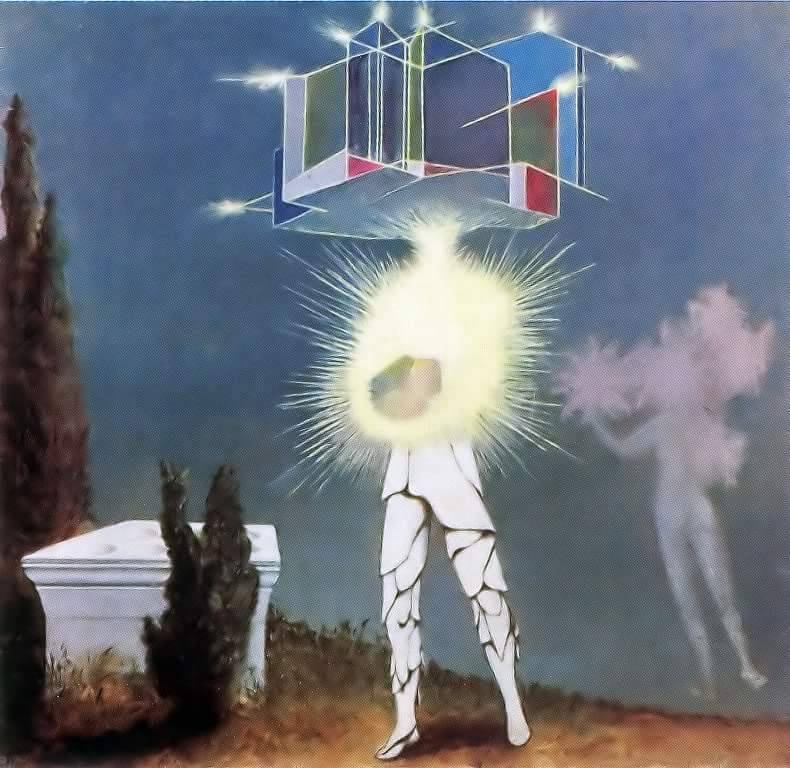

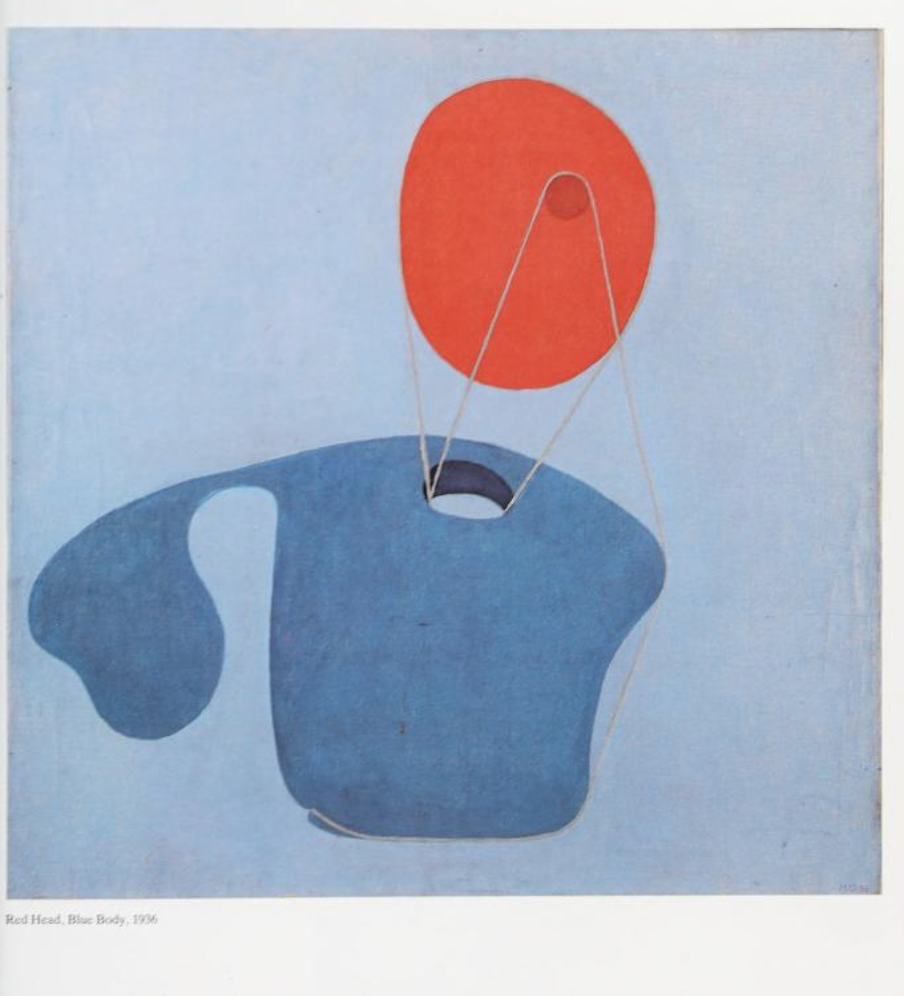

Of course, one can’t forget Oppenheim’s abstract biomorphic collages and shapes echoing her grandmother’s depictions of natural scenes and her memories in the mountains, and the dreamy, phantasmatic painted scenes no doubt inspired by her interest in Carl Jung, spurred on by her psychoanalyst father who would attend Jung’s weekly seminars. She had already started recording her dreams at the age of 14.

Before the creation of her tea cup, it was her paintings that spurred Giacometti and Hans Arp to invite her to exhibit as soon as they laid eyes on them.

Sure, her name doesn’t slide off the tongue as easily as Dali’s, but Meret Oppenheim deserves a better seat amongst the great artists of the 20th century. And we can think of a few others history forgot … Leonor Fini, Maruja Mallo, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. We’ll keep looking, you spread the word.