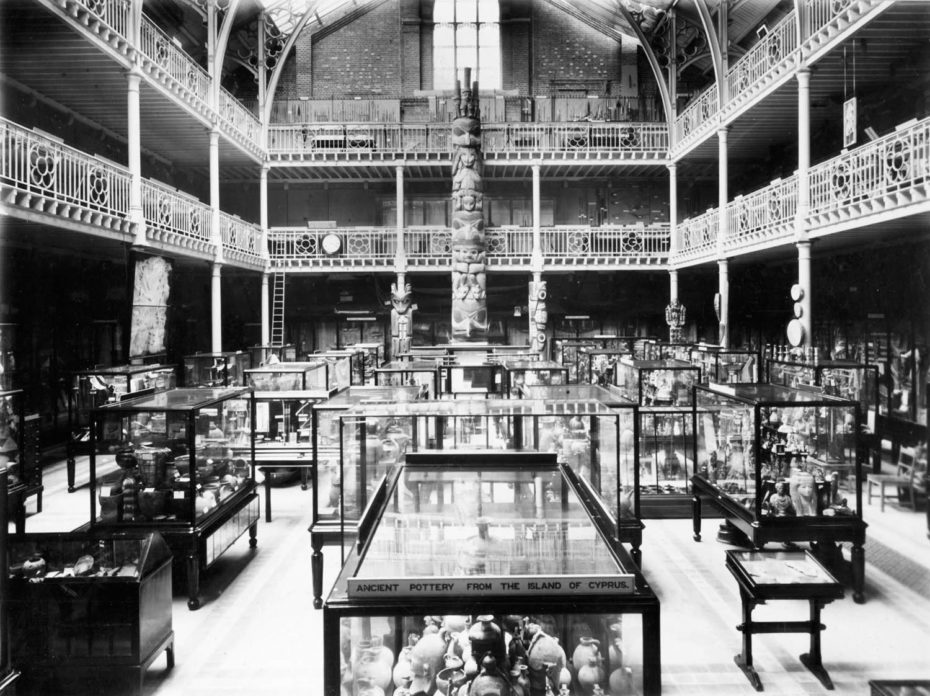

It almost feels like you’ve clicked on something you shouldn’t have and suddenly, a door to internet Narnia has opened and you find yourself roaming the aisles of a huge maze of glass cabinets, overflowing with an insane amount of objects. You’ve stumbled into the cabinet of wonder that is the Pitt Rivers Museum. Indefinitely closed, like thousands of other cultural institutions around the world due to the coronavirus pandemic, this 136 year-old Victorian museum hiding within another museum in Oxford, England, is free to roam at the click of your mouse – every glass cabinet, every last aisle, all to yourself. And what a beautiful sight it is to discover, even if only from behind your screen for now.

It’s the place with the notorious shrunken heads that inspired a scene in Harry Potter; a place where you can find Yorkshire funeral biscuits next to Chinese burial headdresses. You start to realise, this is not your average collection.

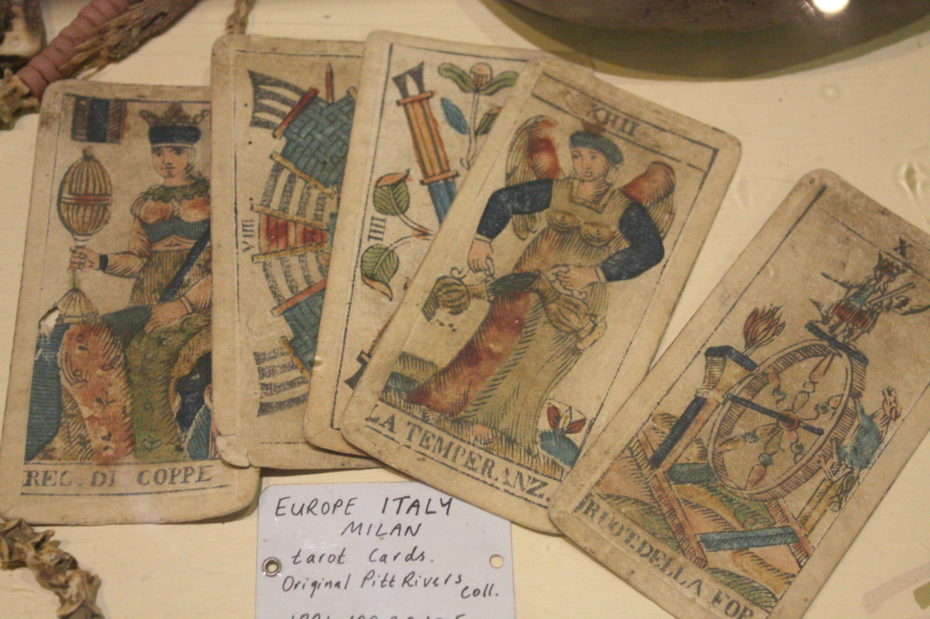

Founded in 1884 by Augustus Pitt Rivers, a devoted Darwinian and collector to out-rank all collectors, his Victorian museum remains almost exactly as he wanted it. The organisation of some 500,000 items has retained its unusual science of “typology”, originally-intended by Rivers. The objects aren’t by separated by civilisation or race or geography like many 19th century collections of its kind. Rather, this maze of objects is arranged into “types”, showing how both everyday, mundane and extraordinary objects evolved like species.

Antique cabinets group together currency, weapons, clothing, musical instruments – almost anything you can think of – and display them side by side from different cultures and times. The shrunken heads in a cabinet labelled “Treatment of Dead Enemies” were made by the Shuar and Achuar people of Ecuador and Peru up until the 1960s. They are displayed next to an Irish warrior’s salt-shrunken heart inside a lead casket.

Before renovations in the early 2000’s, the collection was practically hidden away behind a little door at the back of the Oxford’s Natural History Museum. The collection is now better indicated and easier to find, attracting a larger footfall, which has perhaps brought with it some necessary changes. For the past few years, the museum has become an advocate for “cultural decolonisation,” starting the conversation on how to re-evaluate the many colonial prizes in museum collections across the country.

“We can’t undo history but we can be a part of the process of healing,” says the director of the museum, by meeting with originating communities to address errors and gaps in the information it stores, and to discuss repatriation. So far, the museum has returned 28 objects to indigenous peoples, and plans to hand back more. Even the notorious shrunken heads may disappear as the museum is currently in talks with representatives of the Shuar people of the Amazon rainforest over the future of the religious objects. For now, they’re still on the virtual tour.

In another initiative run by Pitt Rivers, prior to the 2020 pandemic closures, the museum was also hiring Syrian refugees as tour guides to provide native-language tours, helping emigrants foster connections between Britain’s cultural heritage and their own.

More recently described as a “meeting point for culture”, the Pitt Rivers Museum is also just a bit like wandering through your quirky grandfather’s attic who traveled through all the coolest parts of history and made a giant collection of what-the-f*ck in some gorgeous Victorian warehouse.

Keep an eye out for the Cannabis sativa from 1896 in the ‘Smoking & Stimulants’ cabinet, mixed with samples of early 1900s tobacco from all over the world. Go on an Easter egg hunt for the egg cabinet. And try the David Attenborough suggestion and don’t read (or google) the labels and try and work out what the objects are for by yourself.

Now if only they’d let us tour the archives.