Forget Atlantis, we want to know more about the mysterious, ancient Cucuteni-Trypillians, who were not erudite space lizards, despite their name, but Neolithic humans whose settlements were so advanced, and so vast, that they pioneered the concept of the city as we know it in Eastern Europe. The trouble is, unlike the cool kids over in Ancient Mesopotamia, these guys left behind no traces of a written language (that we’ve found) to tell us more about them. To make matters more difficult? They intentionally and repeatedly burnt their cities to the ground every 60-80 years. We’re talking total decimation of a densely-populated settlement, home to thousands of people. Did they have a problem with termites? Dragons? Luckily, historians have been left with their intricate clay totems, copper tools, and spiritual treasures. All breadcrumbs to the boggling truth, which is that this society was way groovier than we thought…

Artwork above: Artist Vsevolod Ivanov

The first thing to understand about the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture (which is usually called the “Cucuteni” in Romania and the “Trypillia” culture in Ukraine) is that it wasn’t even discovered until the tail end of the 19th century.

Pior to that, scholars pretty much turned their noses up at the notion that Neolithic Eastern Europe could’ve played a huge role in human advancement. That all changed when a Romanian folklorist, Teodor T. Burada, spotted some strange ceramic fragments…

Burada’s finds opened the floodgates – and he wasn’t alone. Turns out, another self-taught archaeologist named Vikentiy Khvoyka had also discovered remnants of the culture in the Ukraine. Not only had the Cucuteni–Trypillians existed for some 2,000 years (3200-2700 BC) but they had spread from present-Eastern Transylvania to the Ukraine, with the heart in present-day Moldova.

Once referred to as “the garden of the USSR”, the bite-sized country doesn’t have much of a global tourism imprint, though recent years have seen a pique in interest of the area’s wines. Moldova is in fact home to the world’s largest wine cellar, which has its own underground streets where traffic rules apply. If anyone from the Moldova Tourism board is reading: we’d sure love to visit when this is all over!

But we digress. The point is, these discoveries opened up a whole different set of questions about what principles of societal structure, and spiritual worship, these people had. Storied archaeologist Marija Gimbutas was a big champion of the “Sacred Feminine” theory.

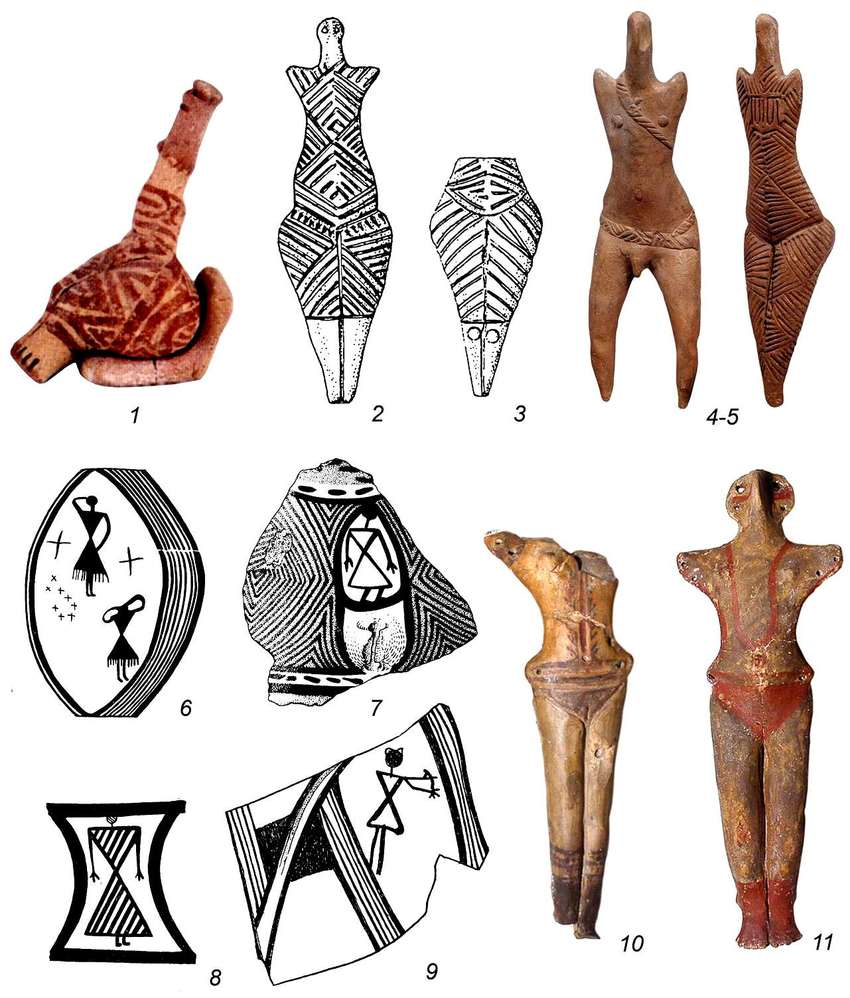

Some basic Venus of Willendorf stuff, you say? Not quite. The level of intricacy to the ceramics, as well as the markings, were unparalleled. Were the markings tattoos? A kind of language? Objects of ceremony? We do know that they believed in a kind of sacred numerology, revolving around the numbers 12, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, and 21; we see them repeated in either patterns or the amount of figurines per site/object.

Evidence suggests that its peak, this was one of the most technologically advanced societies in the world at the time that was constantly developing new techniques for ceramic production, housing and agriculture.

Even today, we can’t figure out how to replicate the artistry of some of their ceramics. In an interview with Radio România Internaţional, researcher Constantin Preoteasa stated that, “with all our modern methods, traditional craftsmen are trying to reproduce Cucuteni ceramics, but with inferior results […] no human community has reached the level of refinement that the Cucuteni craftsmen have.” A specialist in Egyptian archaeology, Dr. Roger S. Bagnall, also told The New York Times that “Egyptians were certainly not making pottery like this.”

As late as 2013, another “construction [site] was discovered. with two hearths,” historian Dan Monah told Radio România Internaţional. They excavated another 100-some relics at another village in Iasi County – a testament to how widespread the settlers were, and how they “peopled” every aspect of their life with anthropomorphic objects.

Every object is beautiful in itself. Each has its peculiarity. They make up a pattern that is specific to no other culture and sticks to the mind.

Romeo Dumitrescu, Cucuteni pottery collector (Radio România Internaţional, 2013)

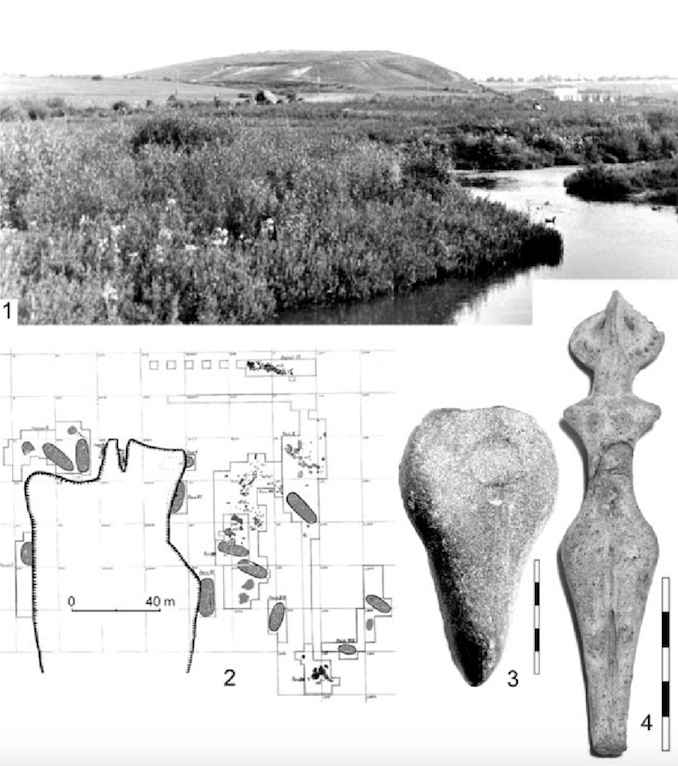

Thousands of structures have also been found belonging to the Cucuteni-Trypillians, with almost all identified by geo-magnetic exploration – not digging – under those quiet green hills. They revealed a mastery of “wattle and daub” style homes as well as log buildings, and semi-underground houses, or bordei.

Please enjoy this delightful nerd rendering of Talianki, one of biggest Trypillian mega-sites…

A lot of these archaeological discoveries were happening in the 1980s, and into the present. and they all revealed traces of methodical, ceremonial burning. Namely, the discovery of a site known as “Poduri,” in Romania,” that revealed thirteen habitation levels that were built on top of each other over years and years. Sacred religious chambers were also discovered at their centre with female idols.

(Insert hashtag: #GodisaWoman).

Due to the incredible amount of feminine figurines that have been found, some scholars have (controversially) argued that the Cucuteni-Trypillians were a feminine-led, pacifistic society that survived through skilful trade. There were some male “gendered” objects, but not as many.

Although this culture’s settlements sometimes grew to become the largest on Earth at the time, archeologists haven’t found any evidence of slavery, and believe they were eventually wiped out with the territorial expansion of another culture, the Kurgans, from 3000-2800 BC.

So what’s with the burning and rebuilding?

To intentionally torch an entire settlement, huge amounts of whatever they were using for fuel would have been required, as well as a highly organised community effort. There have been some experiments to try to replicate the results of these ancient settlement burnings, but according to the research, “no modern experiment has yet managed to successfully reproduce the conditions that would leave behind the type of evidence that is found in these burned Neolithic sites, had the structures burned under normal conditions.”

Dragons anyone?

Another theory is that urban renewal played a key factor, even in 5,000 BCE. Their Daub and wattle houses would have been susceptible to deterioration over time and it’s possible that they did have problem with termites – or the ancient equivalent. It could be that they self-inflicted this burning and rebuilding ritual in order to rid themselves of pests (maybe a few witches), and possibly disease too. Talk about a shortage of hand-sanitiser, try keeping yourself alive back then.

And then there’s the “domicide” theory – alleging that the buildings were burned “ritually, regularly and deliberately in order to mark the end of the ‘life’ of the house”. It feels a bit like Midsommar: the Eastern European Edition doesn’t it? While we don’t know if human sacrifices were made, the theory postulates that members of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture believed that inanimate objects, such as houses, had souls or spirits.

But the research still points to a systematic destruction of the entire settlement in order to leave behind the kind of evidence that has been found in the archeological sites.

Could there have been something spiritually symbolic about the cleansing of the city for every generation; a habit of forcing dramatic regeneration upon themselves?

Of the 150 Cucuteni-Trypillian sites that have been identified, it’s worth noting there are no Cucuteni cemeteries (and very few Tripolye cemeteries), leading scholars to believe that they had a profoundly unique relationship to death and grieving that led to the first instances of cremation, or the releasing of the body to Mother Nature via its consumption by birds. (There have been bird goddess statues found on the sites too).

But for the most part, their skeletons just haven’t been found – or if they have, it’s been far away from the settlements. It’s also interesting to note that a select few remains of women and children were found beneath homes, suggesting they may represent the home and familial structure of society. But there simply isn’t enough information about our mysterious civilization for any Ah-Hah! conclusions just yet. For now, we have to wait with bated breath – and shovels – to see what comes next from this curious culture…

The above artwork was painted by Vikentiy Khvoyka (1850 – 1914), a self-taught Ukrainian archaeologist who first introduced Cucuteni-Trypillian culture to the world.