Why did they sell Manhattan for $24 worth of beads and trinkets? That’s one version of the story anyway, about the legendary transaction between the European colonisers and a once powerful indigenous nation. The Dutch called it “New Amsterdam”, and then it became “New York” under the British. But isn’t it about time we all knew the name of the original Native American nation that reigned for a millennia before all that?

Lenape, meaning “the people” or “true people” are the original native New Yorkers and their home was known to them as Lenapehoking. The name Manhattan itself comes from their language. Where subways now rumble and skyscrapers soar, the Lenape harvested oysters, fished and gardened. Today’s West Village would have been the site of ephemeral wigwam villages, while Broadway would merely have been a footpath.

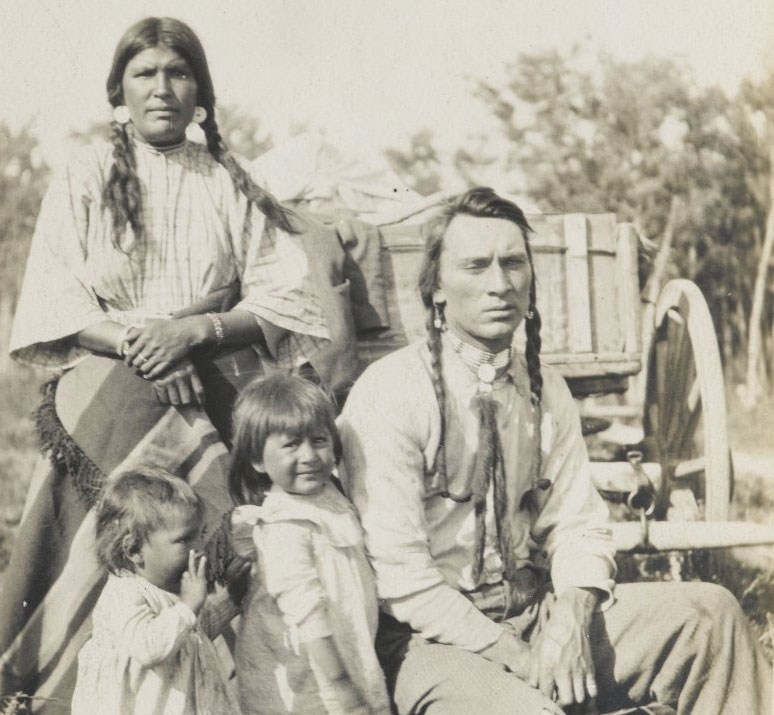

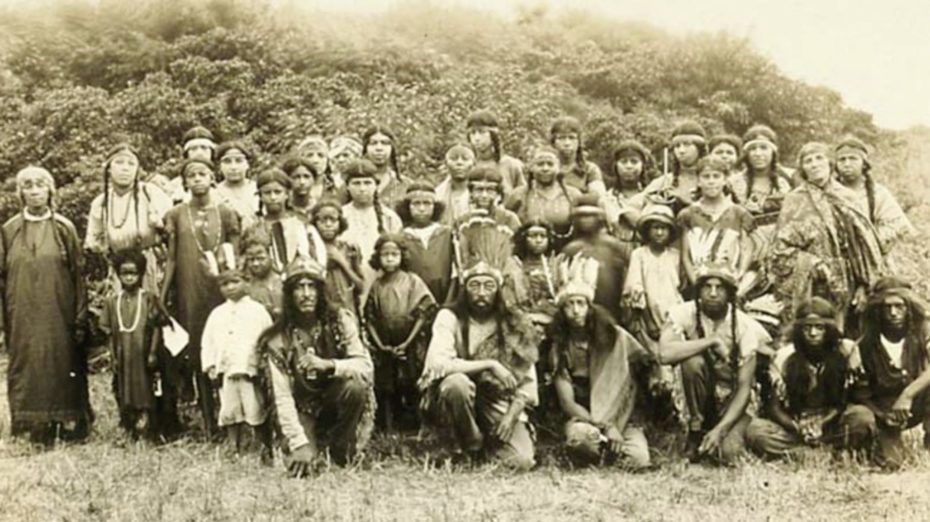

In the summer of 2019, some 300 years after being forced to leave, tribes from across the country returned to their native New York for the first Pow Wow in centuries to celebrate their origin. ABC connected with two descendants of the Lenape for the event:

Most descendants now reside in Oklahoma, Wisconsin and Canada, but just 30 miles from Manhattan, a native American Lenape tribe is still in tact in New Jersey, still fighting for federal recognition as a legitimate tribe (more on that in a moment).

So how were the Lenape so easily swindled out of their land, which once spanned across eastern Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Lower New York, and eastern Delaware?

The famous sale of Manhattan in 1626, which saw Dutch colonist Peter Minuit purchase the island from the Lenape, is a politically and historically muddy story, told solely from the perspective of the colonisers (later packaged neatly into our history books). But the reality is, a lot of land was taken without permission, and the main reason behind that is that there were major cultural differences at play.

The Lenape people had a completely different way of thinking to the Europeans. They were not materialist or experienced traders by nature, and they certainly weren’t a capitalist nation. On the contrary, they were sustainable farmers – yep, long before urban farming became our favourite millennial buzzword, the Lenape were the originals once again. Their way of life revolved around farming and relocating their villages within the range every year or so, returning to previous sites when the land rejuvenated itself.

Most importantly, the concept of “owning land” would have been strange and novel to them, as land was not understood to be “private property”.

As for that transaction made with Peter Minuit in 1626, (thought to be worth $24 in today’s money) – on one side, there’s the Lenape, who would have understood the trade of goods as something like a gift of good faith or an offering with the intention of sharing their land and agreeing to co-exist. Meanwhile the Dutch most certainly understood it to be a sale. The chance that there might not have been a “meeting of the minds” here is high, never mind the language barrier.

From a legal standpoint, a contract can not be enforced if mutual assent is shown to be lacking, which means such a transaction would probably be reversed in court today. And of course, these kind of deals between Europeans and Native American tribes were going on all up and down the east coast.

But within just 40 years of that Manhattan deal taking place, war and foreign disease had already pushed the Lenape to the brink of extinction.

Outnumbered, they were forced to assimilate into the mountains and further out in to the wild west … and well, I guess you know the rest.

If you’re curious to more about the true native New Yorkers, there’s a lot to learn. Interestingly, like many Native American tribes, they were a matrilineal clan, which means that their social system revolved heavily around the importance of women. What must have seemed to alien to the European colonisers is that the Lenape people identified with their mother’s lineage, which included the inheritance of property and titles.

Over in New Jersey, tucked away in the Ramapo mountains with Manhattan’s skyline in clear view, lives a forgotten community of Lenape people. A community of mixed ancestry, including Native American, African and European, their true origins is surrounded by controversy and debate. While 1980 saw them recognized by the state of New Jersey as the Ramapough Lenape Nation, they are still not federally recognized. In an ongoing battle to prove their link to the Lenape tribes, they have been accused of “internalized racism” and falsifying their Native American heritage, initially as newly freed slaves to avoid racism, and later to be seen as “something rarer” according to historian David S. Cohen. It has long been assumed that indigenous Americans didn’t want to assimilate and intermarry to prevent weakening their cultures. But early pioneers and settlers of New Jersey’s mountains included newly free black landowners with some Dutch ancestry that may very well have married Lenape people who were holding out in the woodlands, hoping to stay close to their home.

A 2015 documentary covers the story of the Ramapough Lenape Indian Nation:

(Unfortunately we haven’t been able to find a way to stream this film online).

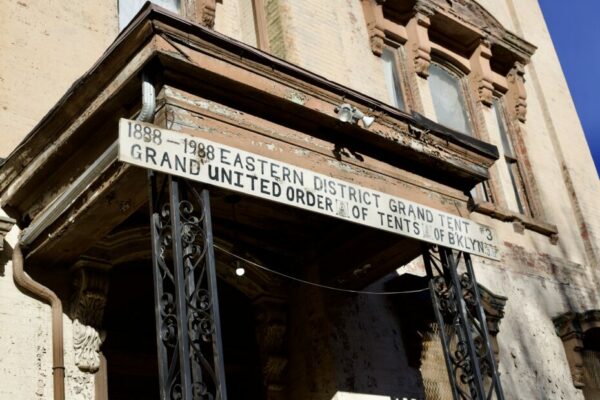

The Island At The Center Of The World by Russell Shorto is also a great book that describes the early relationship between the indegenous people and the Dutch. And of course, the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, currently housed inside the old Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House is a free museum you should visit in Battery Park as soon as cultural spaces are safely re-opened.

In the meantime, we’ll leave you with a few extracts of a message from the Ramapough Lenape Indian Nation about getting through these difficult times:

As we ponder tomorrow, let us remember our grandmother and begin now to help heal the trauma and degradation which has been visited upon her …for surely each wound, each careless and negative act visited upon Grandma is a scar… a wound visited upon our own health, our future and our children… let us use each moment of this time of restraints as a time to heal our families, our old wounds and our forgotten differences… This is a time to celebrate our humanity … The illness which permeates the atmosphere, impacting our health, may be part of the illness visited upon our Mother…. May this be a time to renew our spirits. May we reflect on how to become better people – let us live with purpose, may we take the time to listen and understand … Be good to one another, let us live with love for one another. Be encouraged, let us emerge from this difficulty renewed in our traditions, that bring us joy.

Xwat Anushiik,

Chief Perry of the Ramapough Lenape Indian Nation