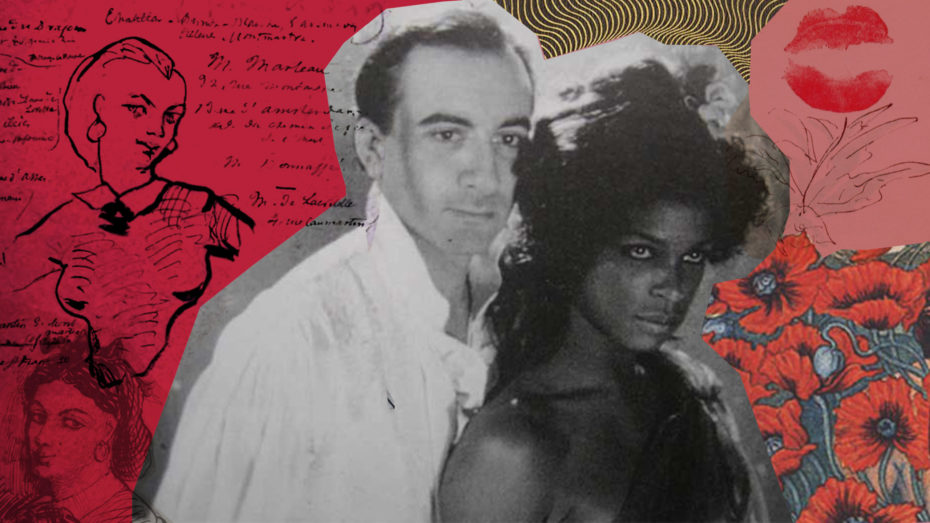

There’s love. There’s lust. Then there’s Jeanne DuVal, who embodied something between the two in her tumultuous relationship with Charles Baudelaire, France’s original “bad boy” poet. As a muse to the rebellious Parisian dandy, she inspired some of the most haunting, revolutionary verses in history – odes to the woman he loved to love, and loved to hate. This 19th century Creole woman who, as a lady of mixed Haitian-French ancestry, never got to tell her side of the story about the poems deemed so raunchy, they went to court in France’s most infamous obscenity trial. “Jeanne DuVal unlocked, in Baudelaire, a secret,” explains historian James Macmanus, “She got to the essence of his art, his poetry. And she did so with great intuition.” Yet, during her own life, DuVal was given an often unattainable, negatively charged presence in the city of Paris – a woman as swallowed up in mystery as she was by the immense, billowing gown in which Edouard Manet immortalised her…

Manet’s painting was radical, simply because it showed a woman unapologetically taking up space. DuVal was described as a very confident woman, who carried herself with all the grace of a royal despite her humble roots. It was part of what attracted a 21-yr-old Charles Baudelaire to her in the first place, when he saw her acting in an amateur play in Paris. The young DuVal has just moved to France from her native Haiti, and was splitting her time between cabaret performances and sex work to finance her acting career. Baudelaire was just about to leave the lukewarm production until she came on stage – so he sat in his chair, lovestruck, for the rest the night, and came again the next evening. This time, with red roses. The decades long romance began…

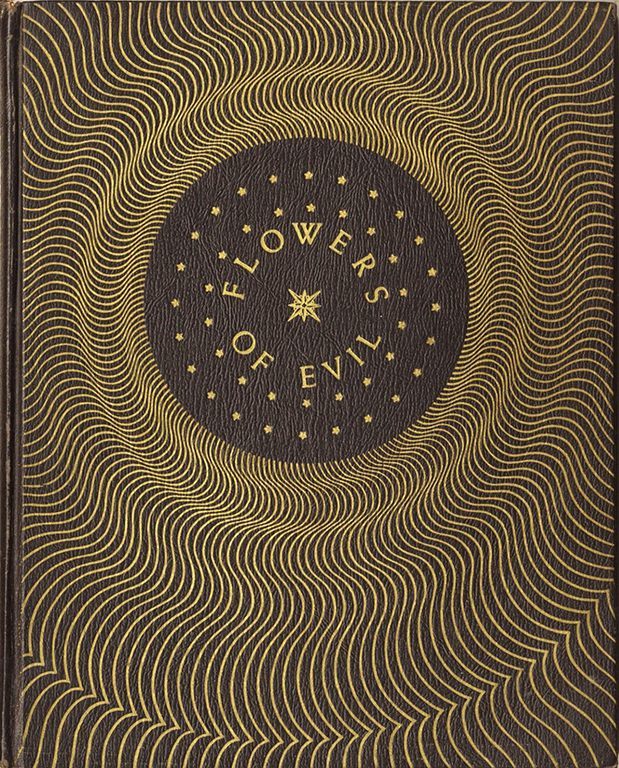

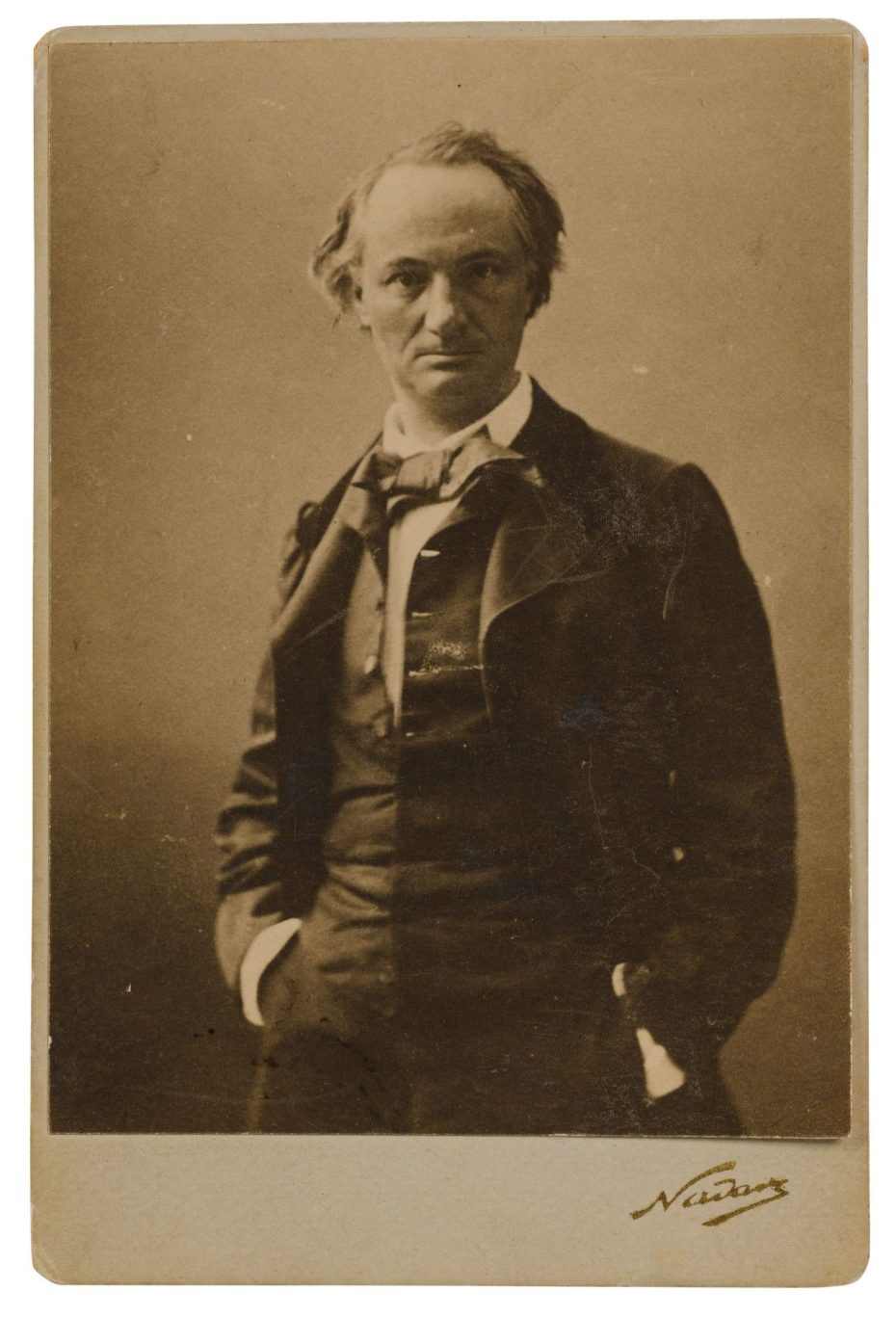

If you’re new to Baudelaire, he was to French poetry what the Rolling Stones were to Rock ‘N Roll. At the forefront of the emerging cultural movement known as Dandyism, he believed his role was to shock society without being shocked himself. He also had no qualms airing his “private dirt,” as the poet Jules Laforgue put it, for the sake of his art, paving the way for T.S. Eliot, Walt Whitman, Serge Gainsbourg, and so many others; many believe he literally invented the French concept of “modernité” for literature largely thanks to his 1857 masterpiece, The Flowers of Evil (Les Fleurs du Mal)…

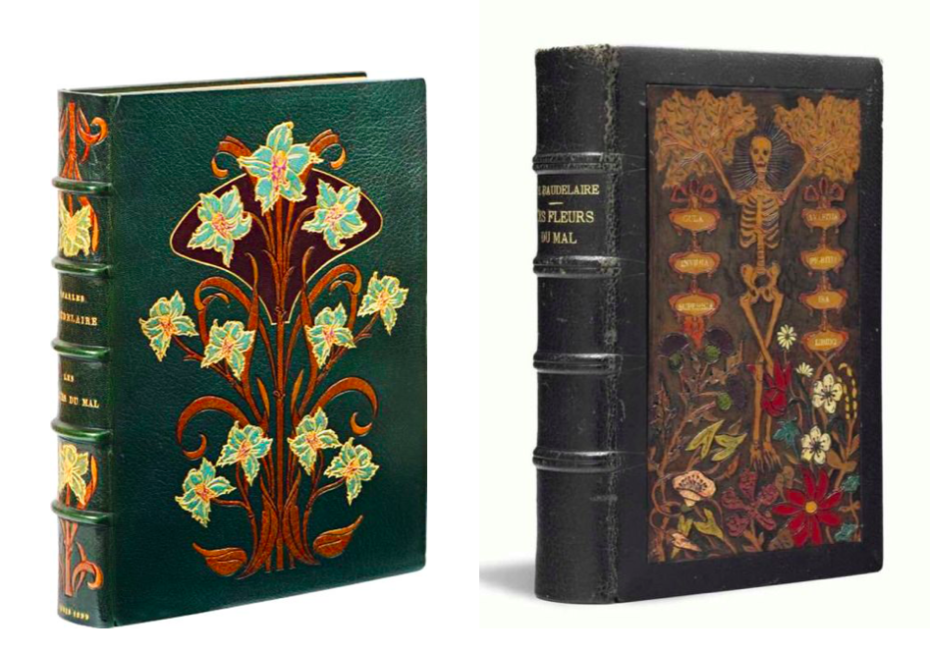

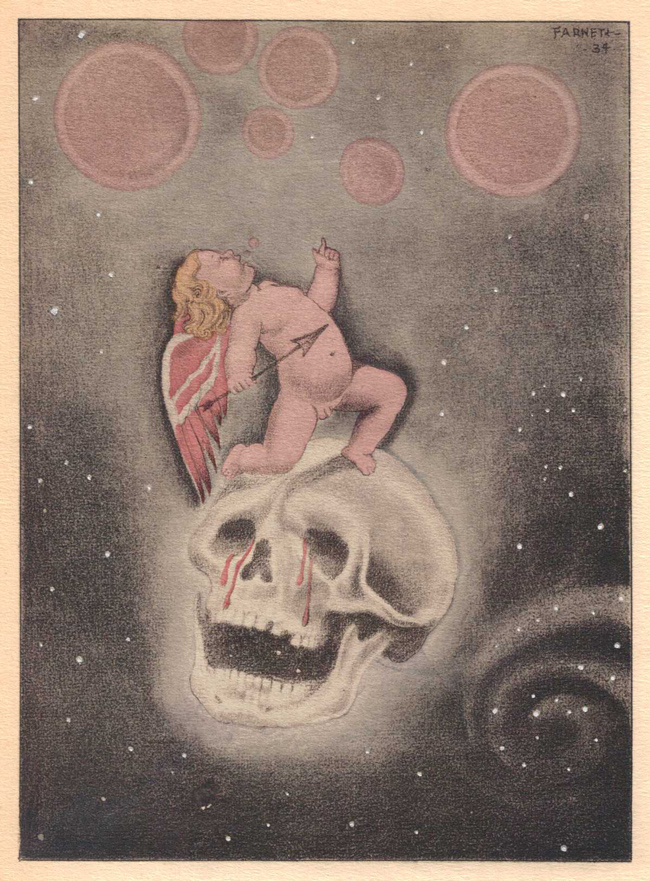

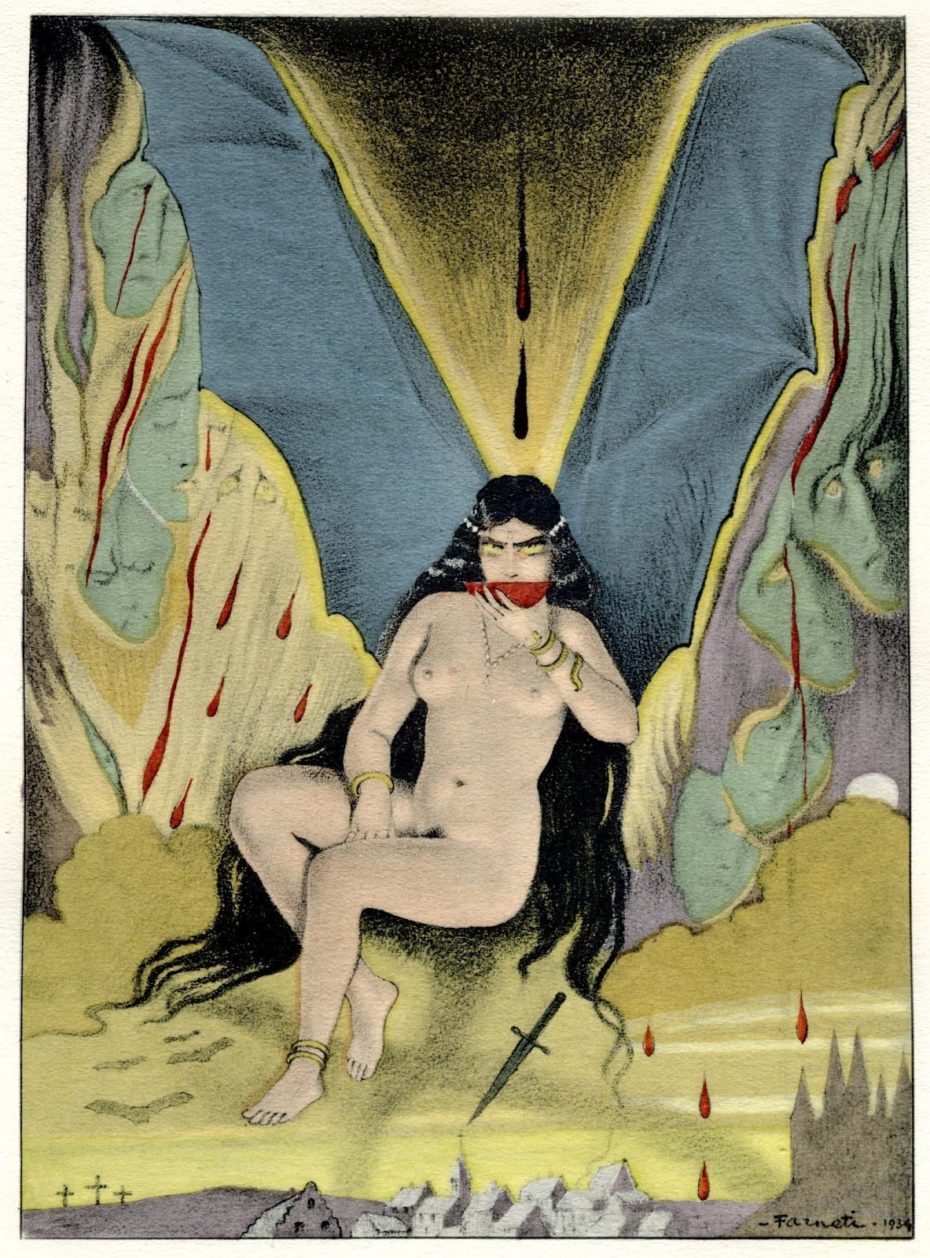

He declared “darkness is itself a canvas” in the collection of poems, whose verses sing of vampires, and “undulating silk”; of “perfume of blood” and “ghostly sensuality.” The illustrations for the various editions capture the vibe quite accurately…

Finally! Here was a man casting his net over all aspects of human feeling, allowing himself to get tangled in the “sinful” – to reconcile the sensual and the spiritual, if only in vain. The poet Jules Laforgue called The Flowers of Evil, “sensual hypochondria shading into martyrdom.” When Gustave Flaubert (author of Madame Bovary) read it, he called Baudelaire “as resistant as marble and as penetrating as an English fog.” Victor Hugo declared it a “nouveau frisson” – a new, titillating thrill.

Of course, the more buttoned-up public was shocked to see Baudelaire eschew Christian values, speaking instead of God’s carnal “dream-voyagers” scaling the Tower of Babel, or of other sensual, “ripe, damned beings” floating through its pages. It was so blasphemous, that six of the poems went on trial in French court and received a ban that wasn’t lifted until after WWII.

It was the lightening rod of modern French poetry – and Jeanne DuVal was the inspiration. In one of its poems, The Dancing Serpent (Le Serpent qui danse), Beaudelaire speaks of his growing intoxication for her…

Like a stream swollen by the thaw

Of rumbling glaciers,

When the water of your mouth rises

To the edge of your teeth,

It seems I drink Bohemian wine,

Bitter and conquering,

A liquid sky that scatters

Stars in my heart!

–Charles Baudelaire’s, The Flowers of Evil

That kind of inspiration held a certain power over him, however. For as much joy as the relationship gave, it also revealed some of the uglier aspects of humanity. Check out the 180 he pulls in his poem, “The Vampire,” about DuVal:

You who, like the stab of a knife,

Entered my plaintive heart;

You who, strong as a herd

Of demons, came, ardent and adorned,

To make your bed and your domain

Of my humiliated mind

–Charles Baudelaire’s Les Fleur du Mal (The Flowers of Evil)

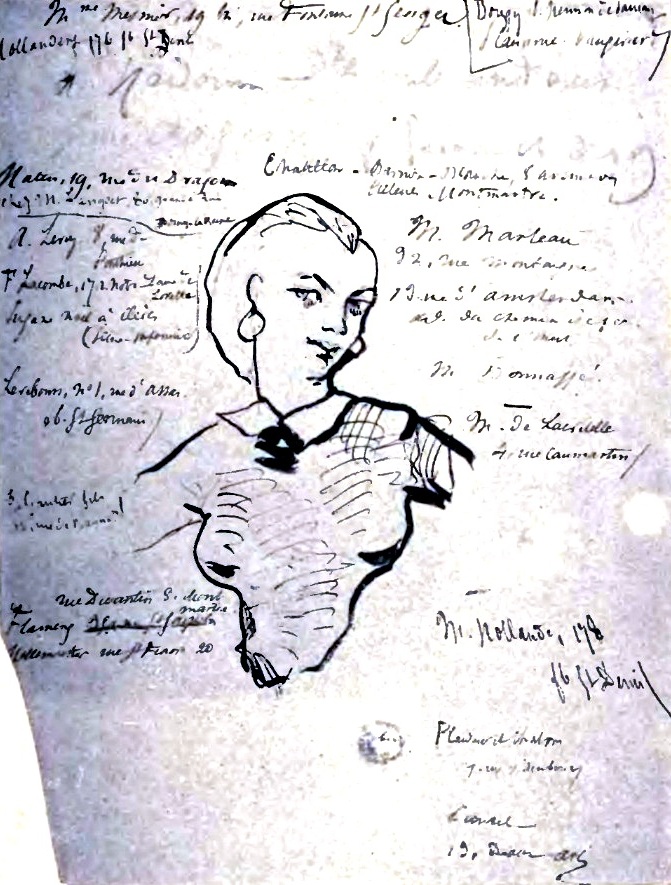

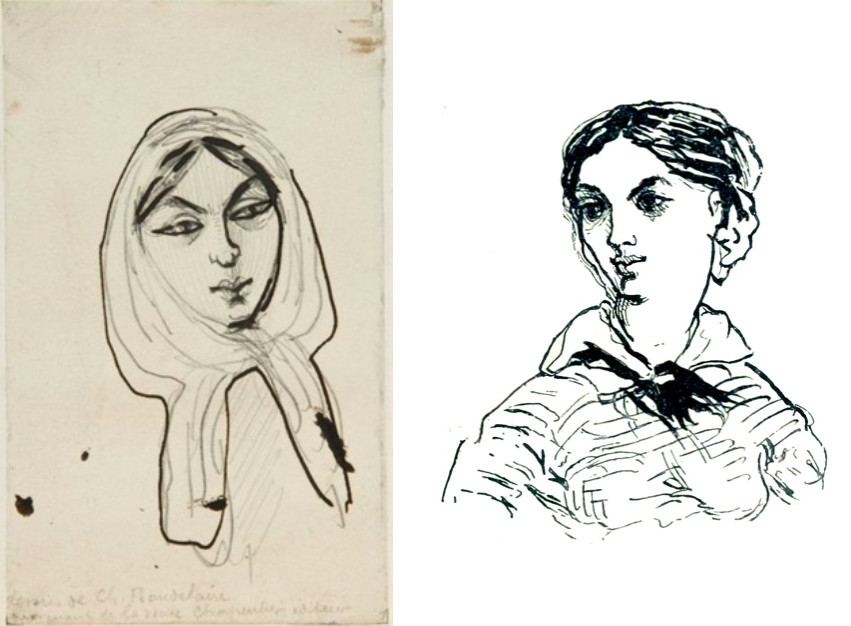

So, yes, mixed signals. Through it all, an infatuated Baudelaire continued to doodle portraits of her in his notebooks. To this day, they’re some of the best clues we have to her true likeness. Despite a handful of images circulating the net under her name, no verifiable photographs of her are believed to have survived.

Why was their relationship so tempestuous? History has had a tendency to pick apart Jeanne DuVal, and call her a user who “drained him of money at every opportunity.” Baudelaire himself, who had a penchant for visiting with women of the night from a young age, called her his “mistress of mistresses.” And maybe she did see her twenty-year relationship with Baudelaire as a means to improve her situation as an unmarried Creole woman living in 19th century France. What we can be sure of, is that she also challenged and inspired Baudelaire, who was a difficult man with peculiar habits.

He was known to grind his hash into green jelly for his toast. As Paris’ original dandy, he first defined such a figure in society as having “no profession other than elegance… no other status, but that of cultivating the idea of beauty in their own persons… he must live and sleep before a mirror.” Rebellious and free-spending, Baudelaire could be seen as a semi-bourgeois shopaholic with lavish taste (and debts to prove it), yet, in 1848, Baudelaire aligned himself with the French Revolution and the overthrow of the constitutional monarchy. He was the kind of guy to relish the drama of drawing lines in the sand, only to place his footing on both sides.

DuVal, on the other hand, didn’t seem to want to belong to anyone other than herself. “The poet’s feelings for DuVal ran the gamut from deep passion to absolute hatred,” writes Dolan. Sadly, time has only rendered her even more of a mystery.

It’s said she was jaw-droppingly gorgeous, rather tall, and of course very independent. Maybe not the best long-term match for Baudelaire, who was desperately devoted to his dear Mama – and she was no fan of Jeanne DuVal, creating further tension. Baudelaire said that next to his mother, DuVal was the woman he loved most in life, and in a letter to his mother at the age of 36, wrote, “believe that I belong to you absolutely, and that I belong only to you.”

Baudelaire was a troubled man. He had lost his father at a young age, and maintained a love-hate relationship with women. Particularly when it came to Jeanne, whose identity as woman of mixed-race ancestry renders the situation even more complex. His many DuVal-inspired poems are laden with potentially exotic-fetish turns of phrase for his “Black Venus,” and one imagines the scrutiny the mixed race couple must have received 200-years-ago.

There was a lot of pressure for their relationship to exist as fuel for his writing. Did he love DuVal as her own woman, or as his muse – as his lifeline? In the twenty year ping-pong match of their love, it seems like DuVal was always triumphant. Always composed, and a little less needy. After one of their separations, a weepy Baudelaire wrote to his mother, “As far as I am concerned, even if I’m headed for more luck, pleasure, money or fame – I know that I will miss this woman forever.”

He was even caught doodling pictures of her in the notebook of his next lover, Apollonie Sabatier:

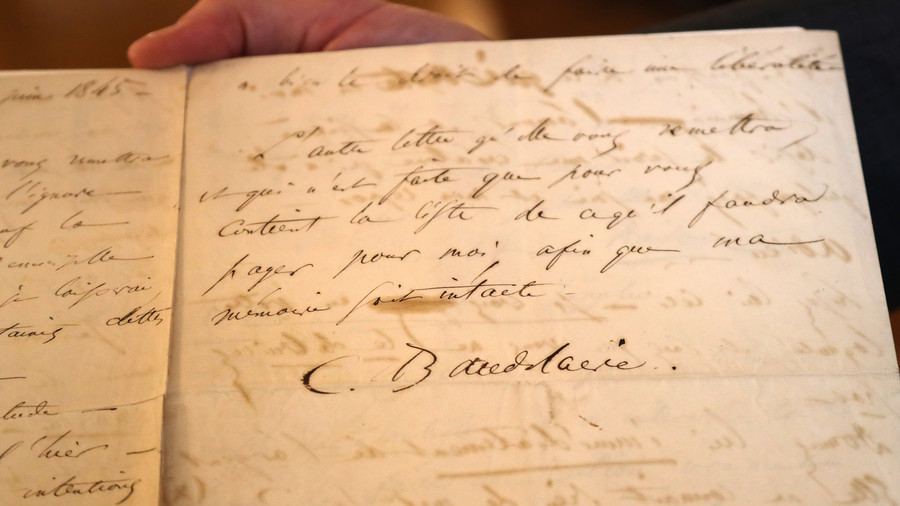

One of the more haunting artefacts we have of their union is a letter preceding his (failed) suicide attempt. Pictured above, it sold at auction for $267,000 in 2018.

In what also has to be one of the most spiteful moves in art history, DuVal was literally and symbolically erased from Baudelaire’s life in a painting by his pal, Goustave Courbet, after (what we can presume) was one of their many ruptures.

A closer look reveals the ghostly figure of DuVal to the left of his head:

It was DuVal’s decision to end the relationship for once and for all in 1861. As Baudelaire wrote in a letter to his mother, she believed him too stubborn to change. Still, he continued to financially support her, to love her in his own way until he died in 1867 at just 46-years-old from syphilis. So grief stricken was his mother that she destroyed all but one or two correspondences between DuVal and her son. As for DuVal? No one even really knows if she died before or after Baudelaire. As his lover, she too had contracted syphilis, and some say she died a few years before him while others claimed to have seen her living out her days on crutches in the Batignolles area of Paris, suffering heavily from the disease.

To walk in the footsteps of their romance is to take a stroll into the heart of Paris’s island on the Seine in the shadow of Notre Dame. At No. 6 of Rue le Regrattier on the Île Saint-Louis, you can still see her apartment building. One can just imagine the days and nights Baudelaire spent pacing outside, but of course, there is no plaque to commemorate Baudelaire’s mysterious mistress.

We might add that When DuVal lived there, it was known as “Street of the Headless Woman” (rue de la Femme-sans-tête) – an inscription you can still see carved onto one of its corner:

Thus, the book closes on the mysterious DuVal. At least we’ll always get to revisit her in The Flowers of Evil (which you can buy on Amazon, or, hey, from an independent bookseller!)

We’ll leave you with Serge Gainsbourg’s song, “Baudelaire,” which beautifully turns the poet’s sensual stanzas for The Dancing Serpent into song. DuVal would’ve like it, don’t you think?