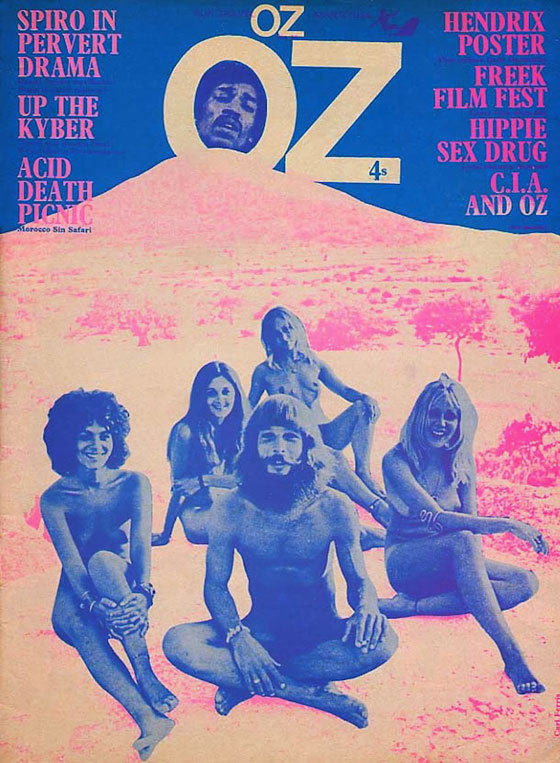

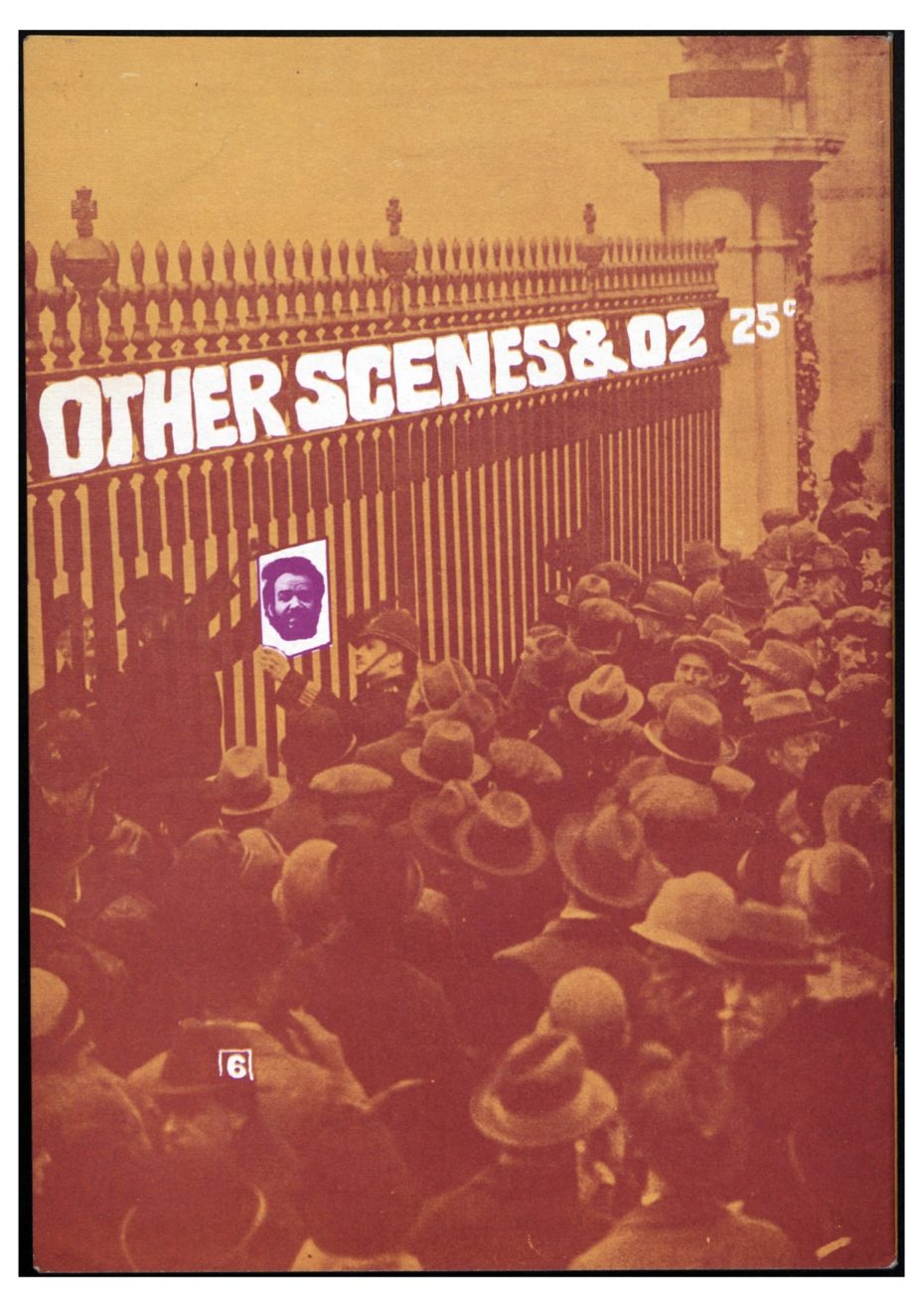

Let’s go back for a moment to the swinging sixties in London’s Notting Hill. Portobello Road is the main artery of the hippie movement, heaving with bohemians musicians and freethinking “freaks”, as they’re known to the establishment. Jimmy Hendrix hasn’t yet taken a fatal overdose in his flat and British counter-culture is on the rise. With it comes a revolutionary agenda for an alternative society, one that can be communicated through its own underground magazines and newspapers like IT and Frendz, served with a strong shot of psychedelic content. The publication on everyone’s lips, however, is Oz; the one all the rock n’ roll stars are talking about at parties. It’s thought-provoking, trippy and packed with erotic taboos. And in the tradition of the most influential avant-gardists, like Oscar Wilde and Charles Baudelaire, it’s about to become the subject of the longest obscenity trial in Britain’s history.

In an age where nothing we read seems to shock us anymore, we’re taking a look back at this iconic literary zine of the Swinging Sixties before turning our attention to the underground press still going strong and making a difference in today’s digital world….

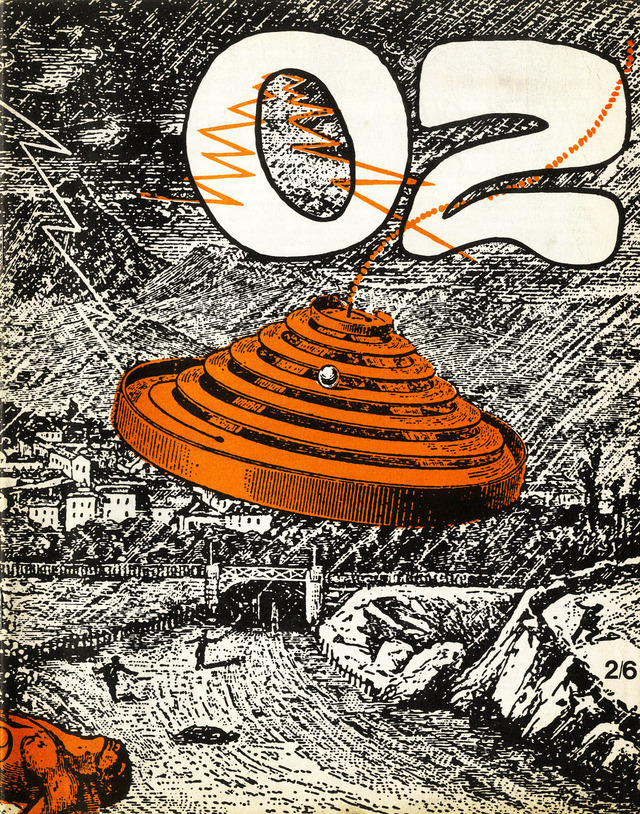

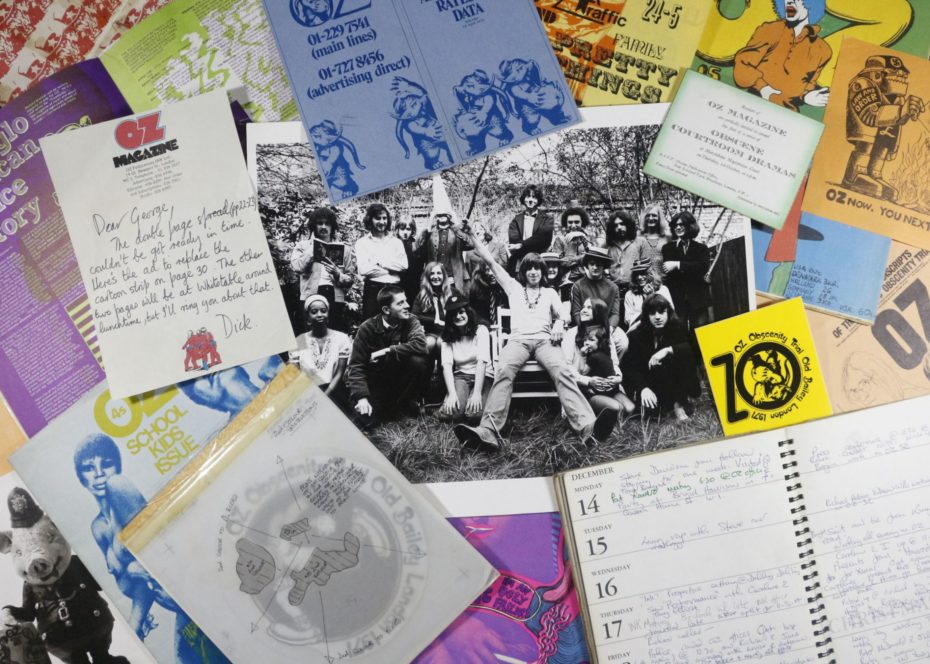

Oz was originally conceived in Sydney, Australia, by three rebellious students Richard Neville, Richard Walsh and Martin Sharp. The independent publication tackled back-street abortions in its first issue. It was released on the morning of April Fools’ day in 1963, and by lunch time, 6, 000 copies had been sold. By issue 3, the editors had been charged for distributing an indecent and obscene publication.

Still, they kept going, and in issue 5, criticised Australia’s xenophobic police for harassing gay people. Most of those magazine copies ended up in a government furnace. While appealing a prison sentence for hard labour, the group of 20-something friends, agreed it might be time to spread the word from more enlightened pastures.

In 1966, after an exhaustive fight against the Australian establishment, Neville and Sharp made their way to England via Europe and Asia on the Silk Road, a rite of passage for any self-respecting pot-smoking intellectuals of the day.

London was the perfect place to plant the seed of Oz. At the start of 1967, the British parallel of Oz magazine was born in Richard Neville’s Notting Hill basement flat, where it would become the zenith of the Australian publication, if not of all counter-culture publications of the era.

Neville was the leader of the gang; the driving force throughout the whole endeavour. Marsha Rowe, who worked for Oz in Sydney and London, and later co-founded the feminist magazine Spare Rib in the 70s, said that “He was a man who inspired others; he was a catalyst and innovator, who displayed a charisma that was sometimes the envy of others.”

He had no problem making friends with London’s most influential intellectuals, anarchists, outlaws and rock ‘n’ roll royalty, like Eric Clapton:

“Sharp stumbled into a bar shortly after his travels and struck up a conversation with a long-haired guitarist. Sharp had a poem he had written in Nepal and the guitarist was looking for lyrics to a piece of music. He handed the musician the poem on a napkin. The guitarist was Eric Clapton, whose song, “Tales of Brave Ulysses,” would be immediately published as the b-side to the hit single “Strange Brew.””

Andrew Hannon

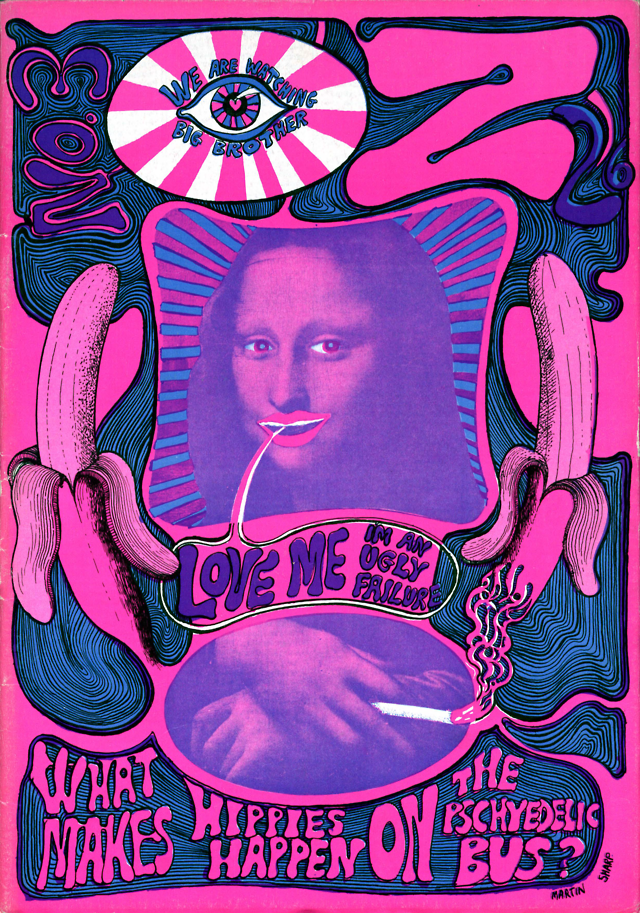

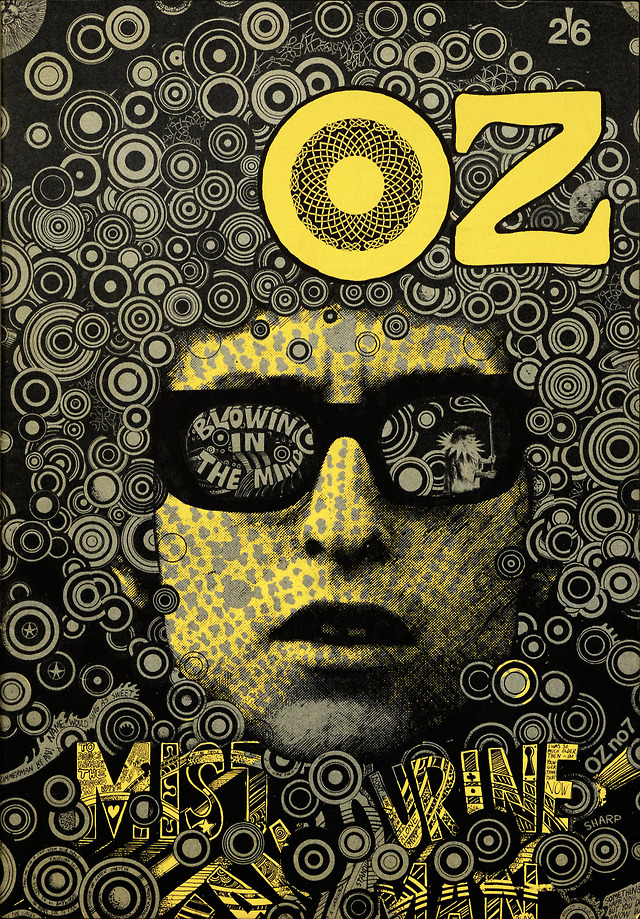

And then there was Martin Sharp, now considered Australia’s foremost pop artist, who was responsible for the wizardly visuals of Oz. You would recognise his work on Eric Clapton’s albums with Cream.

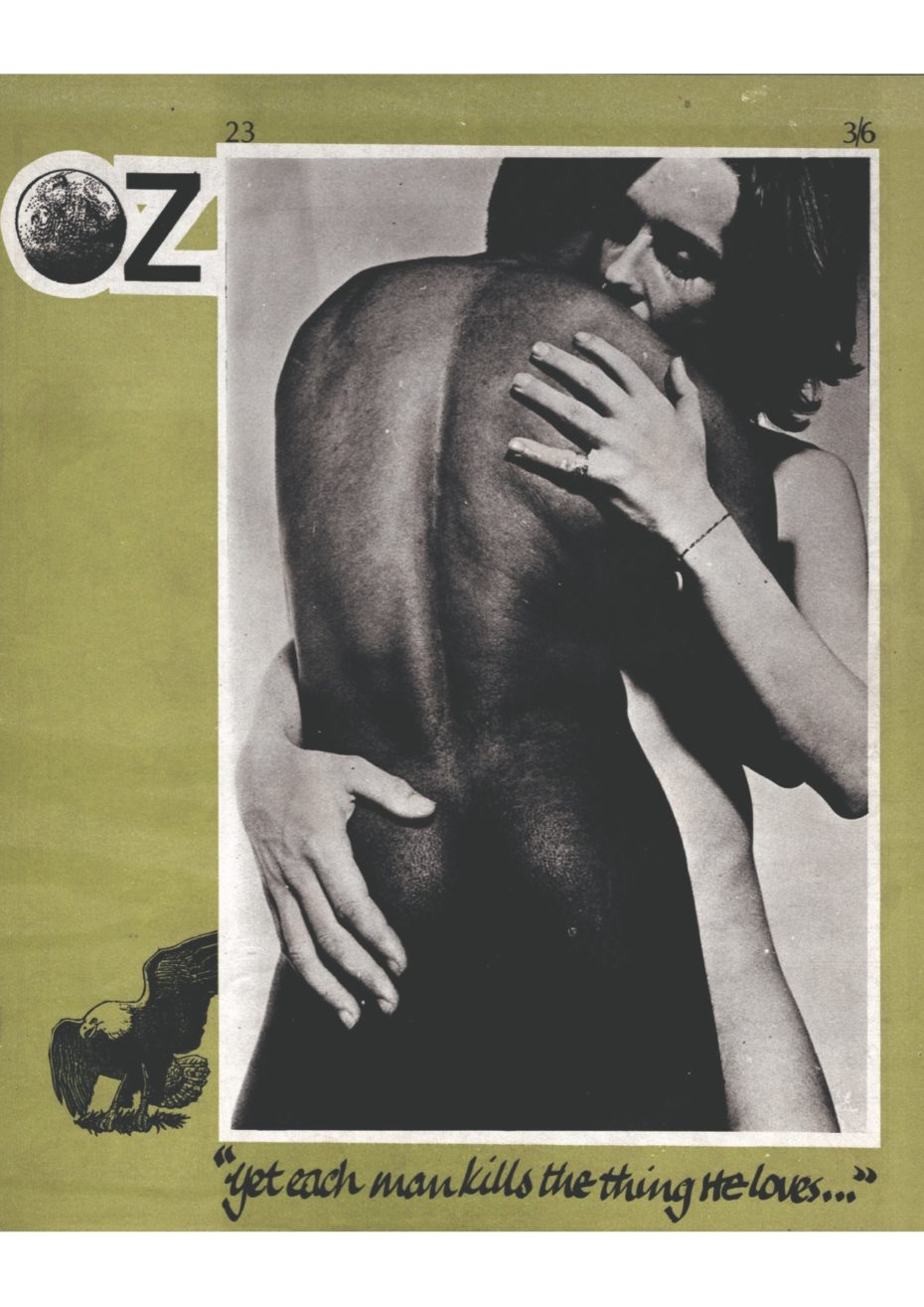

The use of offset printing (and maybe a little help from a few hallucinogens) gave Sharp more freedom in his artistic direction with Oz. The introduction of new colours and fluorescent hues made it standout amidst a wave of underground zines as one of the most recognisable and visually exciting publications of the 1960s. David Hockney also produced a poster for the magazine, which could be ripped out and pasted on bedroom walls. The eleventh issue included collectible psychedelic stickers.

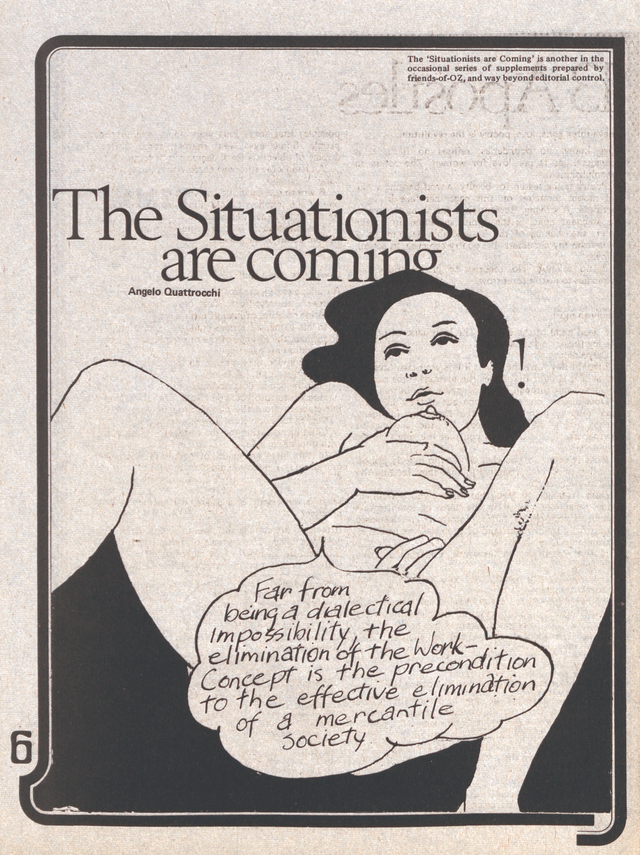

Interviewees included Pete Townsend, Jimmy Page, and Andy Warhol. Contributing writers included the feminist writer Germain Greer who provoked English society with lines like, “I would never go to bed with an Englishman”. The editors let loose on politics and encouraged New Left theories, student activism, psychedelics, sexual liberation, new age ecology, and much, much more. Mick Jagger was raving about Oz to his rockstar friends, and the magazine became a driving force that was hard to ignore.

Of course, such a revolutionary, anti-establishment publication couldn’t avoid some kind of punishment, even if they had escaped it in Sydney. And without doubt, London’s Metropolitan police were out to get underground press. It wasn’t long before they raided the offices of Oz.

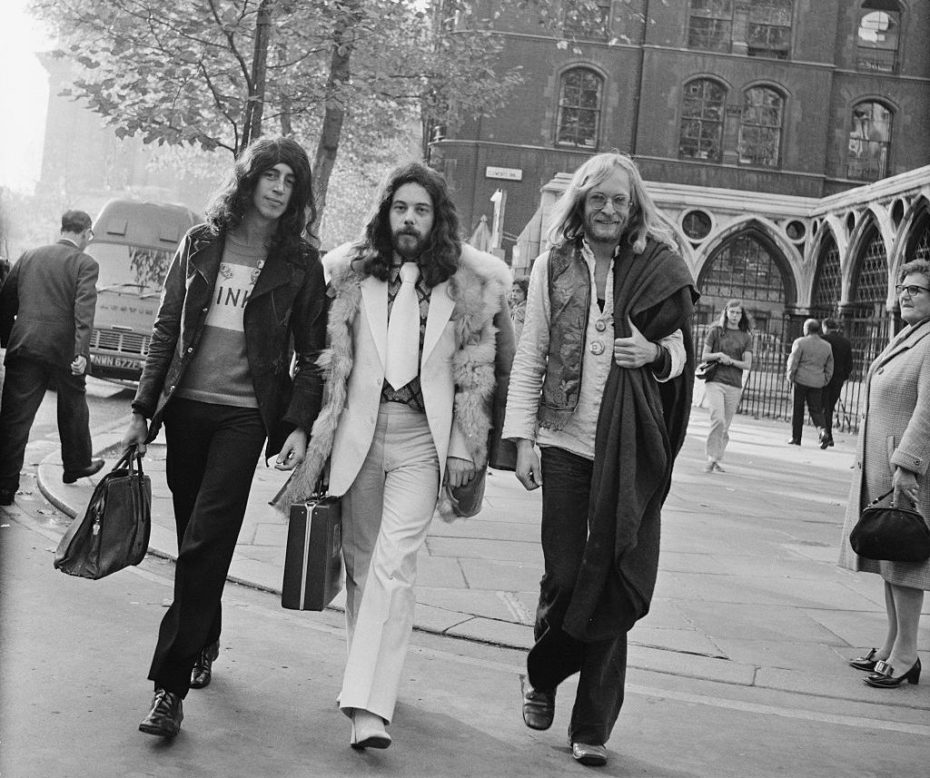

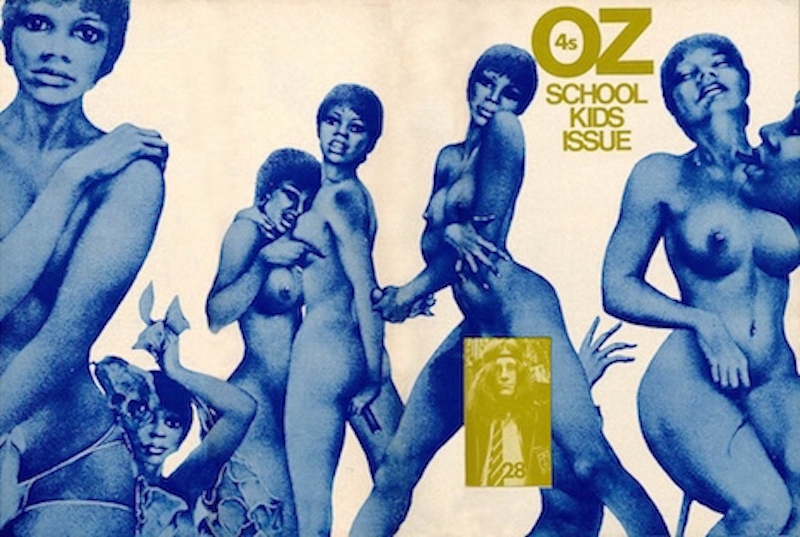

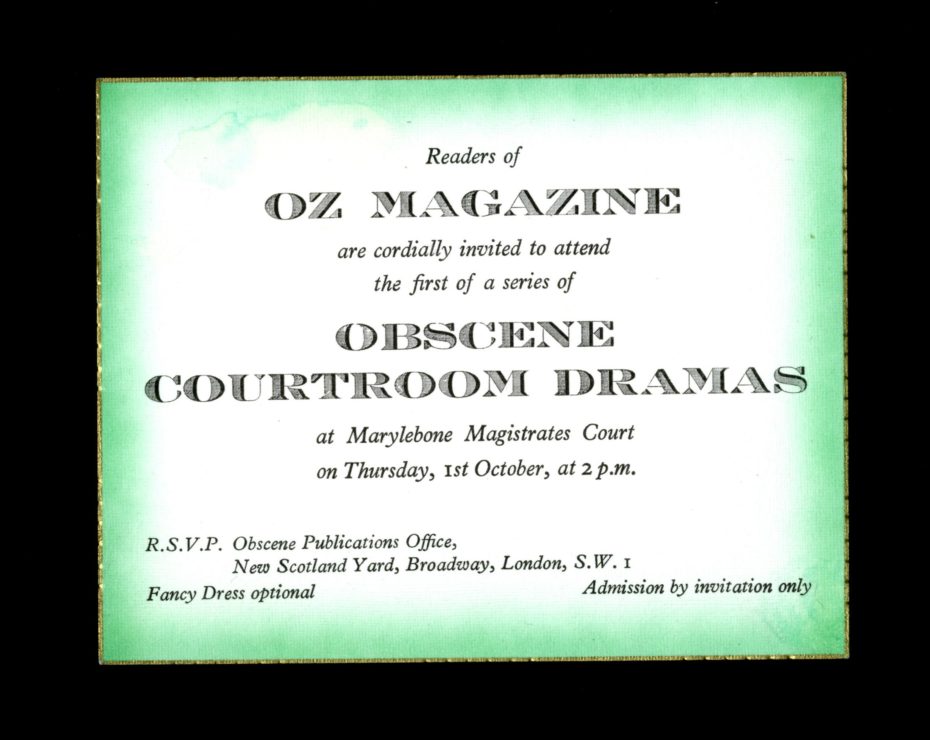

By 1970, with the counter culture scene pumping out new variations of underground magazines every month, the Oz team decided it was time to take new risks. And by risks, we mean, they let a bunch of school kids take the reins and edit their own May issue of the magazine, which they renamed the Schoolkids Oz. And it was that guest issue would land them at the centre of the longest ever obscenity trial in British legal history.

The establishment had found the perfect opportunity to make all kinds of mavericks tremble in their boots. One of the contributors, a 15 year old schoolboy, had created a sexually explicit cartoon of beloved kid’s character, Rubert the Bear. It was deemed obscene, and all three acting adult editors of Oz at the time – Jim Anderson, Felix Dennis and Neville – were accused of “conspiring to corrupt public morals”, a charge whose sentence had no limits, meaning that they could even have been imprisoned for life.

Outcry from readers and heated debates surrounding censorship ensued, even long after the trial had finished, and many feared grave consequences for free-speech if the defendants were found guilty. The Times newspaper received even more letters about the trial than they did about the Suez crisis, and an effigy of the judge was burnt outside the courtrooms.

None other than John Lennon himself had put together the Elastic Oz Band with Yoko Ono and released the record “God Save Oz” (later changed to “God Save Us”) in order to raise funds in support of the Oz team.

After a nail-biting stretch of six weeks, the trio weren’t convicted for the conspiracy charge, but were found guilty of smaller offences and were sent to prison, where their long hippie locks were cut, causing even more indignation. In the end, the Oz team eventually won their appeals and were released, on the grounds that the judge had misdirected the jury.

Today, every issue of the legendary psychedelic newspaper, is available on the web, thanks to the University of Wollongong, including the Australian version.

The explosion of underground press in the 60s, paved the way for off beat publications. So is there still space for groundbreaking periodicals like it today?

Certainly. Today’s “zine” culture is very much the love child of the 1960s underground press and the internet, which has helped bring the cost of production to almost zero, from the design to the distribution. With the continued existence of censorship around the world, underground press still exists to expose, discuss, and debate forbidden subjects.

Speaking to Zolima City Mag, archivist Elaine Lin explained why there’s currently a resurgence of underground press in Hong Kong, particularly in the form of zines. “The 2014 Umbrella Revolution protests … and resistance to the hegemony of land developers have been fertile ground for zine creators,” says Lin, and has seen it result in “a lot more zine groups like Zinecoop, zine festivals and even collaborations between zinesters, political activists and established organisations.”

While zines can exist both online and on paper, the printed zine also finds a demand in a political climate where internet censorship is rife.

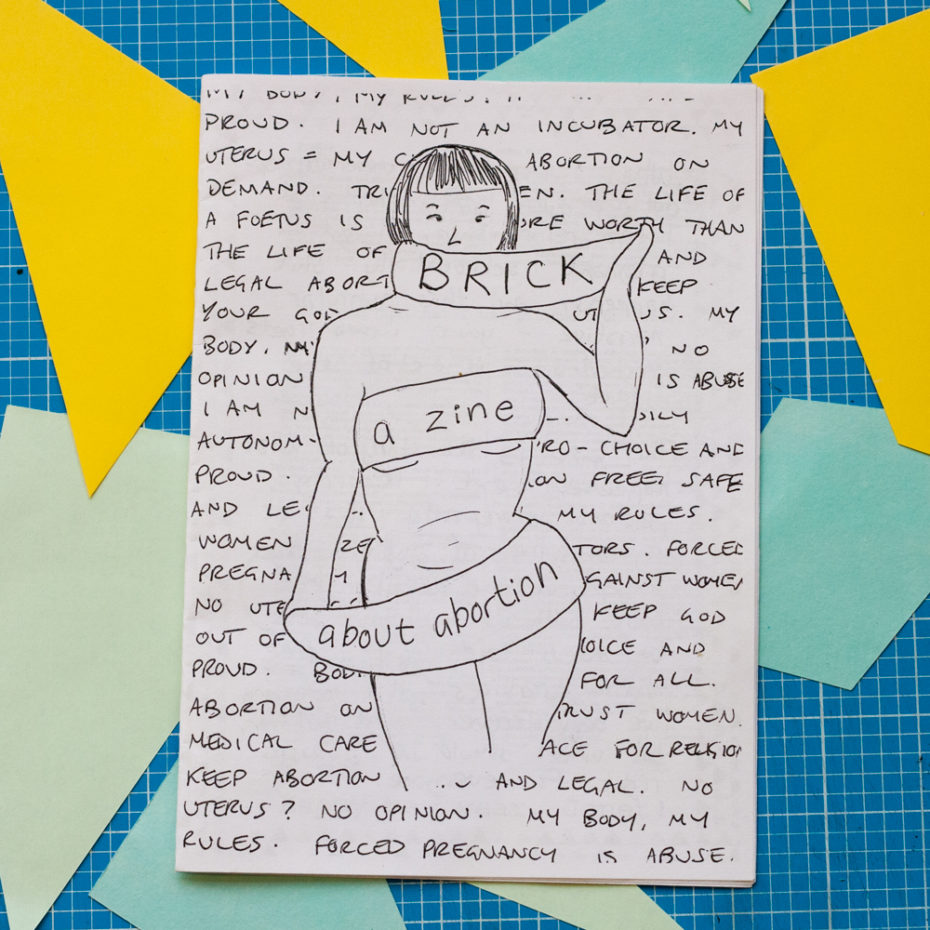

Even though zines date back to the 30s, they had never been so widely created and circulated until the 1960s. With the help of xerox photocopiers, in the 70s the punks made zines, in the 90s the riot grrrls made theirs, and today, new zines continue to emerge every day. These small publications, artistically crafted and self-published by anyone who has something to share with the world, particularly those who feel that their voices are under-represented, continue to evolve in a the digital age.

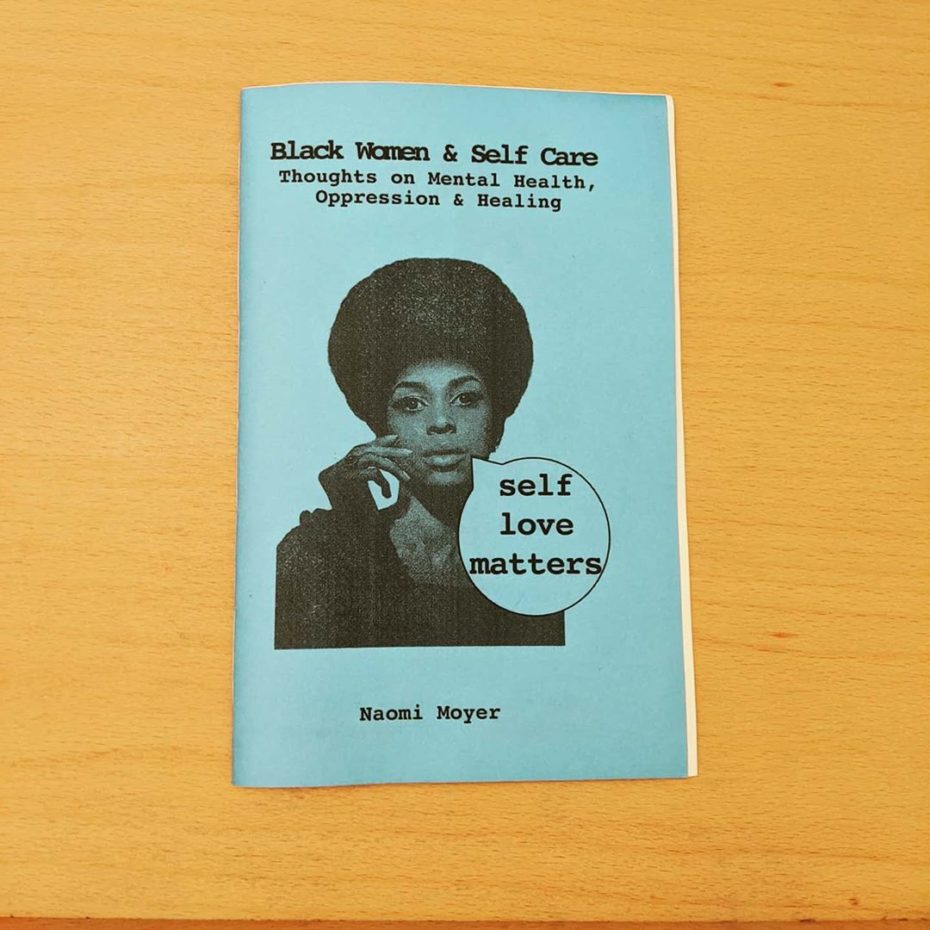

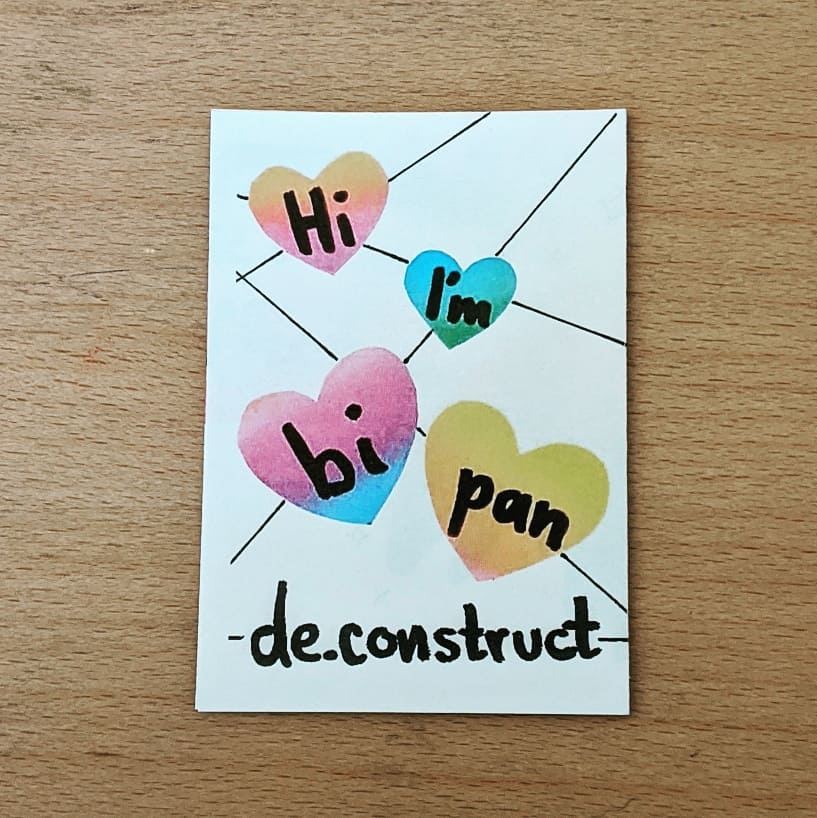

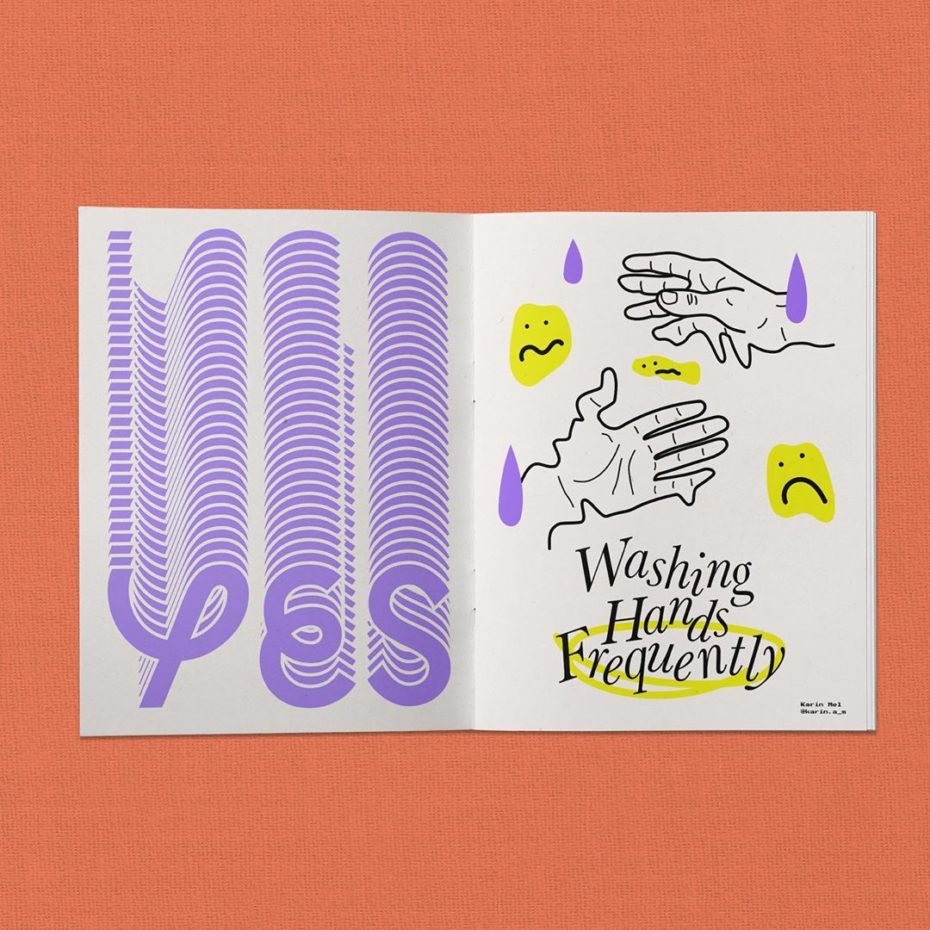

Today’s zines tackle contemporary underrepresented issues, such as mental health, abortion, gender, identity and consent, which are pertinent but explored at limited angles by the mainstream press. There are also zines which respond to today’s world using more abstract, image based methods.

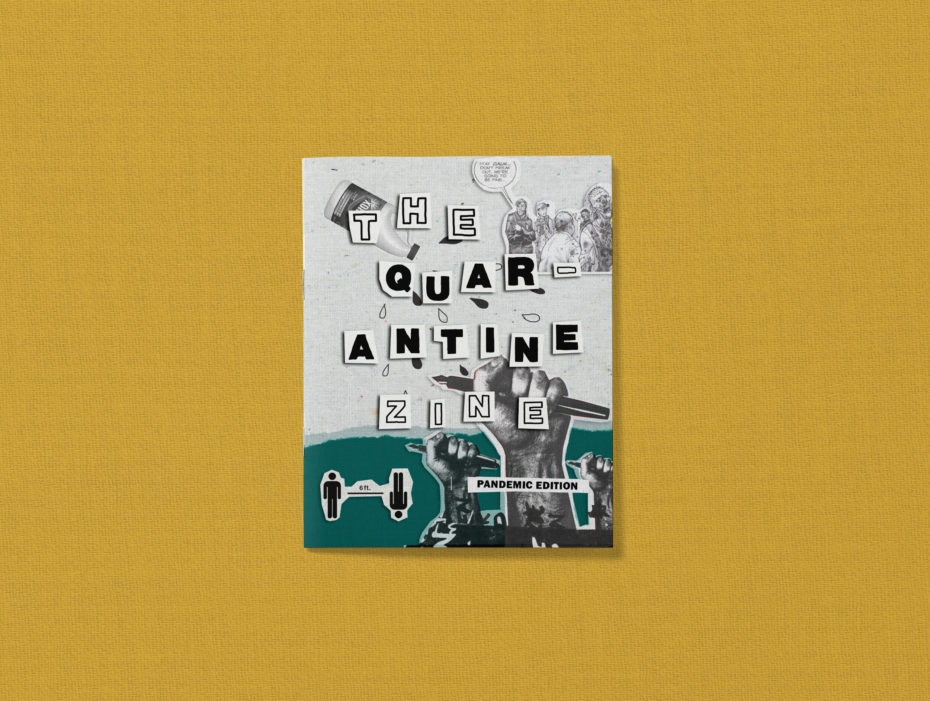

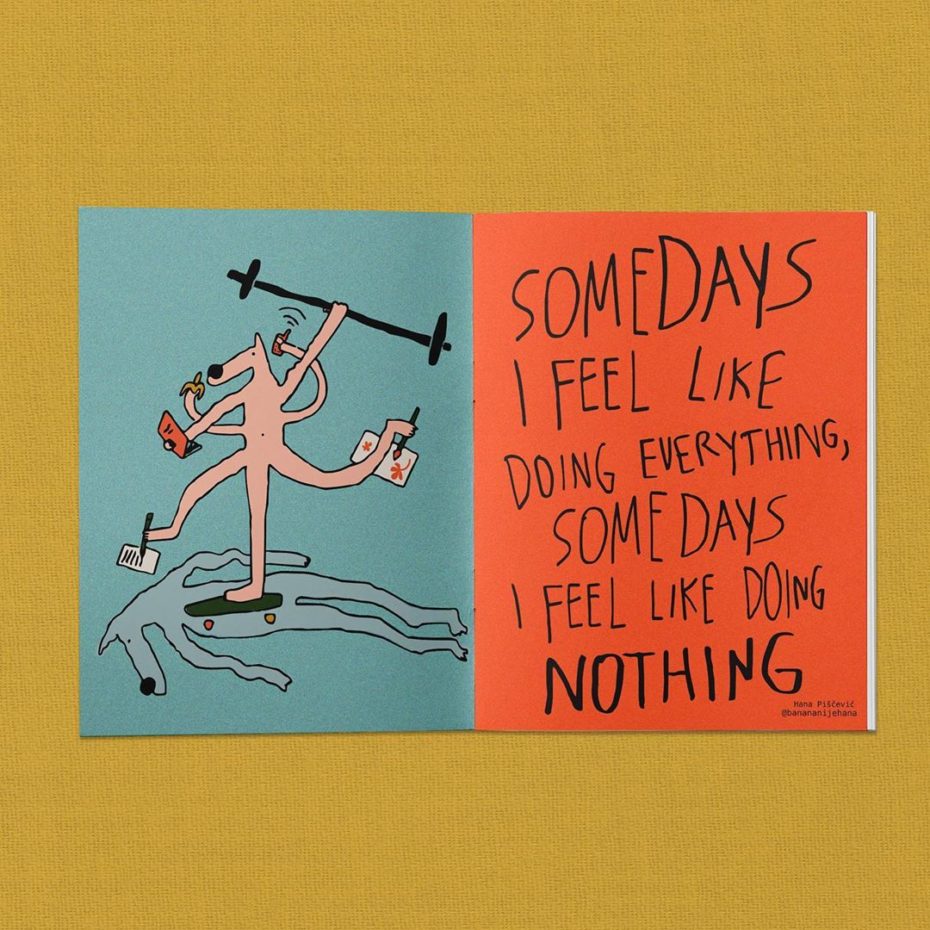

In the response to the Covid-19 pandemic, there’s even emerged “a collaborative zine expressing the feelings and frustrations of being in quarantine” called The Quarantine Zine.

There’s no doubt the underground literary magazines of the 1960s like Oz live on today in carefully considered and crafted zines, which give voices to niche, and even revolutionary, anti-establishment communities in creative and engaging ways. With the presence of the internet and platforms like Instagram, these zines are able to bring communities together more than ever before, while also educating those on the periphery and inspiring new movements and ideas. Working in tandem, the physical copies that continue to exist are a respite in a digital age too. And what’s more, just as the underground press like Oz are a portal to a different time, the zines of today will leave a legacy on a personal scale for posterity.