When the going gets tough, the art gets going. That’s the beautiful thing about human creativity – it can sprout in any soil. Especially for the late British-French illustrator Edmund Dulac, whose flair for Art Nouveau fantasy not only gave us brilliant literary illustrations, but flights of fancy and escape during the First and Second World War. Now more than ever, the story of his life and career trajectory are a sparkling blueprint for our own creative ventures. So let’s flee to the Art Nouveau fantasy illustrations of Edmund Dulac…

Dulac was born in Toulouse, France in 1882. Having completed studies in law, he was going to spend the rest of his life as lawyer when he had a change of heart.

Cher Journal: Well, trouble brewing again. Mon père… Furious upon opening my law books, and seeing page upon page of wizards, mermaids, and unicorns painted by me over “the sacred words.” On explaining to him that these creatures are more real and dear to me than le droit privé [private law], father’s promptly turned the color of a freshly boiled lobster.

Edmund, June 3, 1900

A walk down his particular Memory Lane is a delightful voyage to Paris and London past, from his beginnings studying art at the Left Bank’s Ecole des Beaux Arts and the Académie Julian…

In 1904, at just 22-years-old, he made the move to London and began working for the publishing company “J. M. Dent” to illustrate works by the late Brontë sisters. Not a bad start for a lad during the Golden Age of Book illustration. Dulac adored London (and actually became a naturalised UK citizen), and became a rising star of the illustration scene, networking his tail off at places like the London Sketch Club, and drawing pieces for hot Arts & Culture magazines.

That’s how he landed his dream gig with Leicester Galleries and Hodder & Stoughton publishing company. The gallery proposed commissions from Dulac, and exhibited them annually while also granting the rights to Hodder & Stoughton for reproduction in gift books. Considering Leicster was where Pablo Picasso and Camille Pissarro had their first solo exhibitions in England, it wasn’t too shabby.

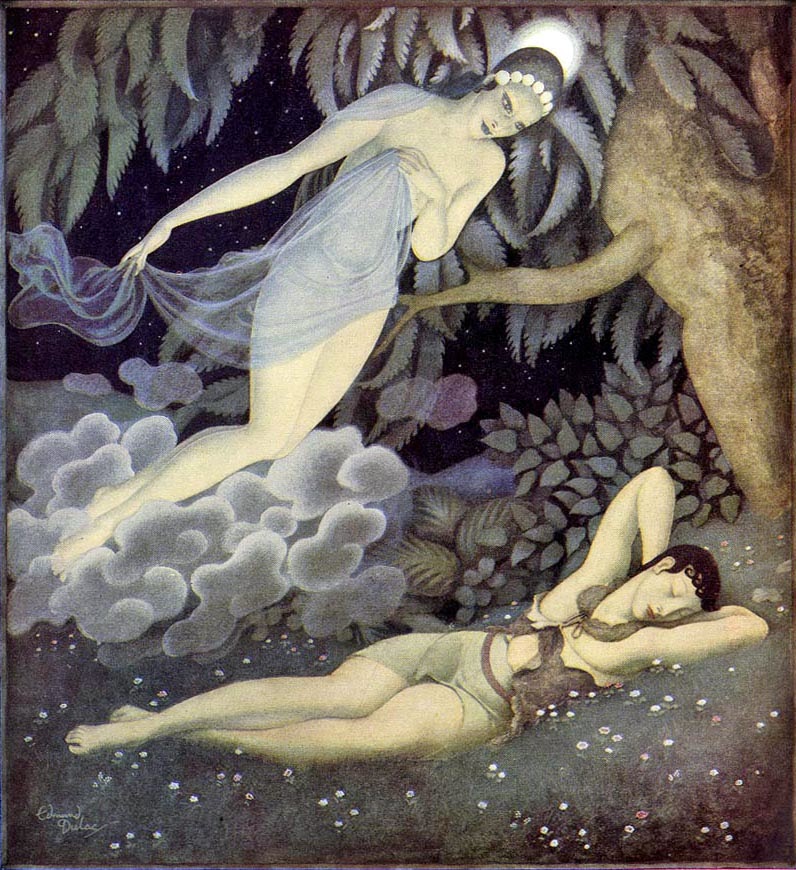

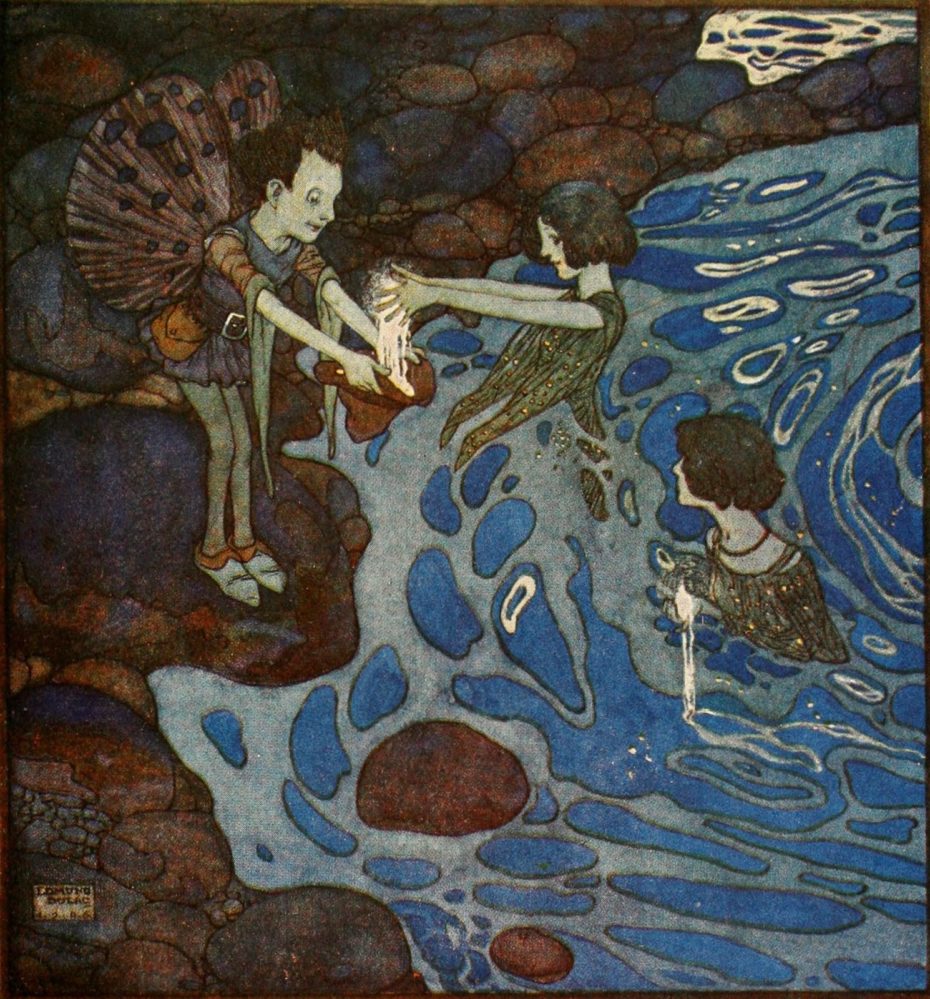

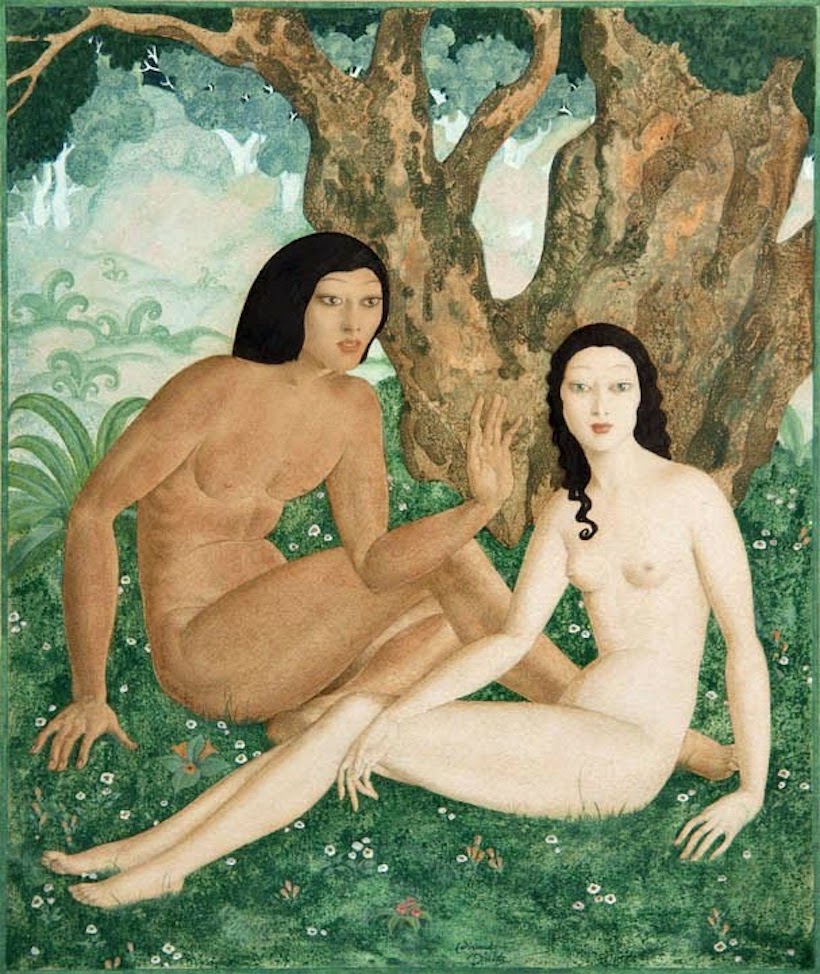

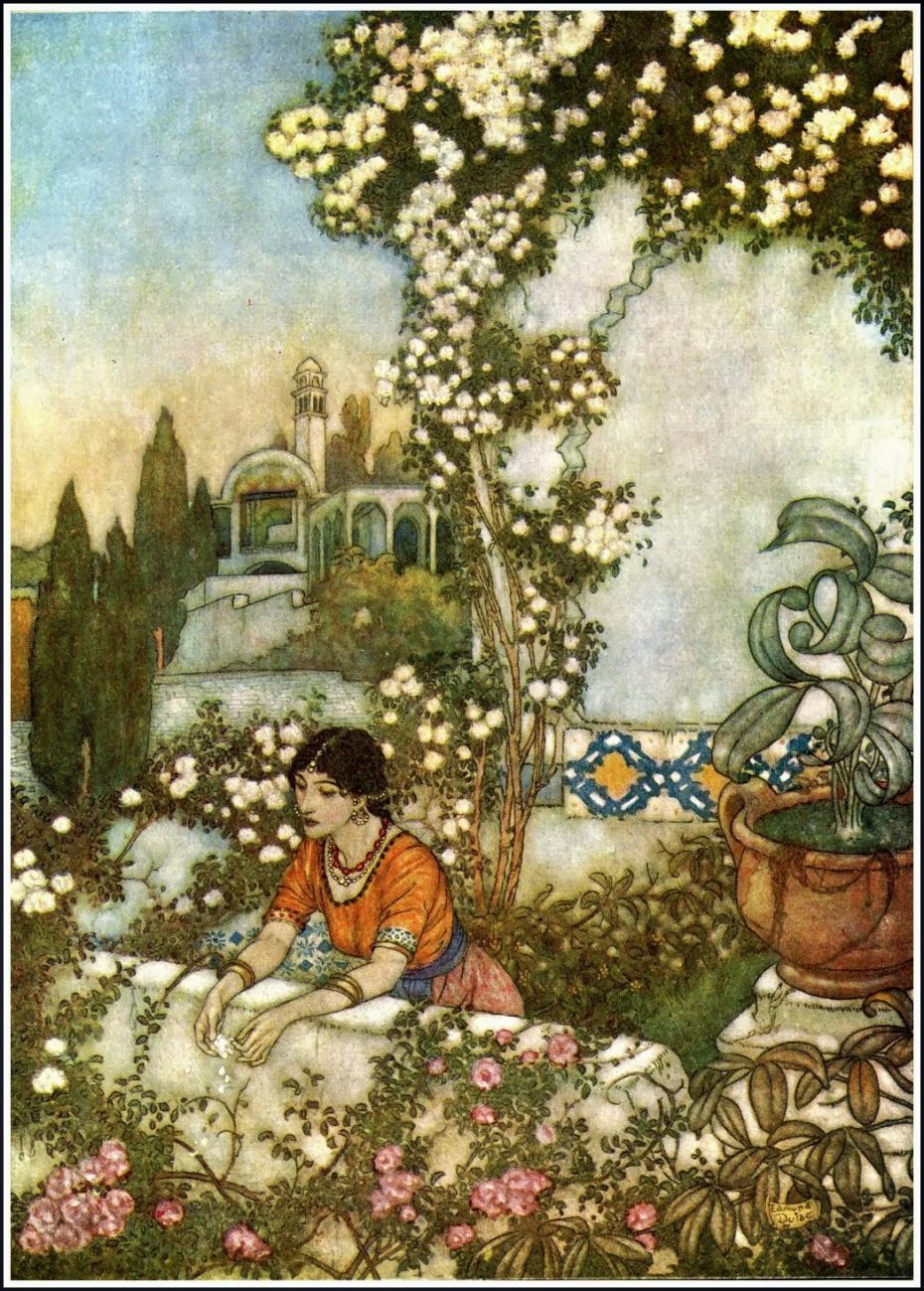

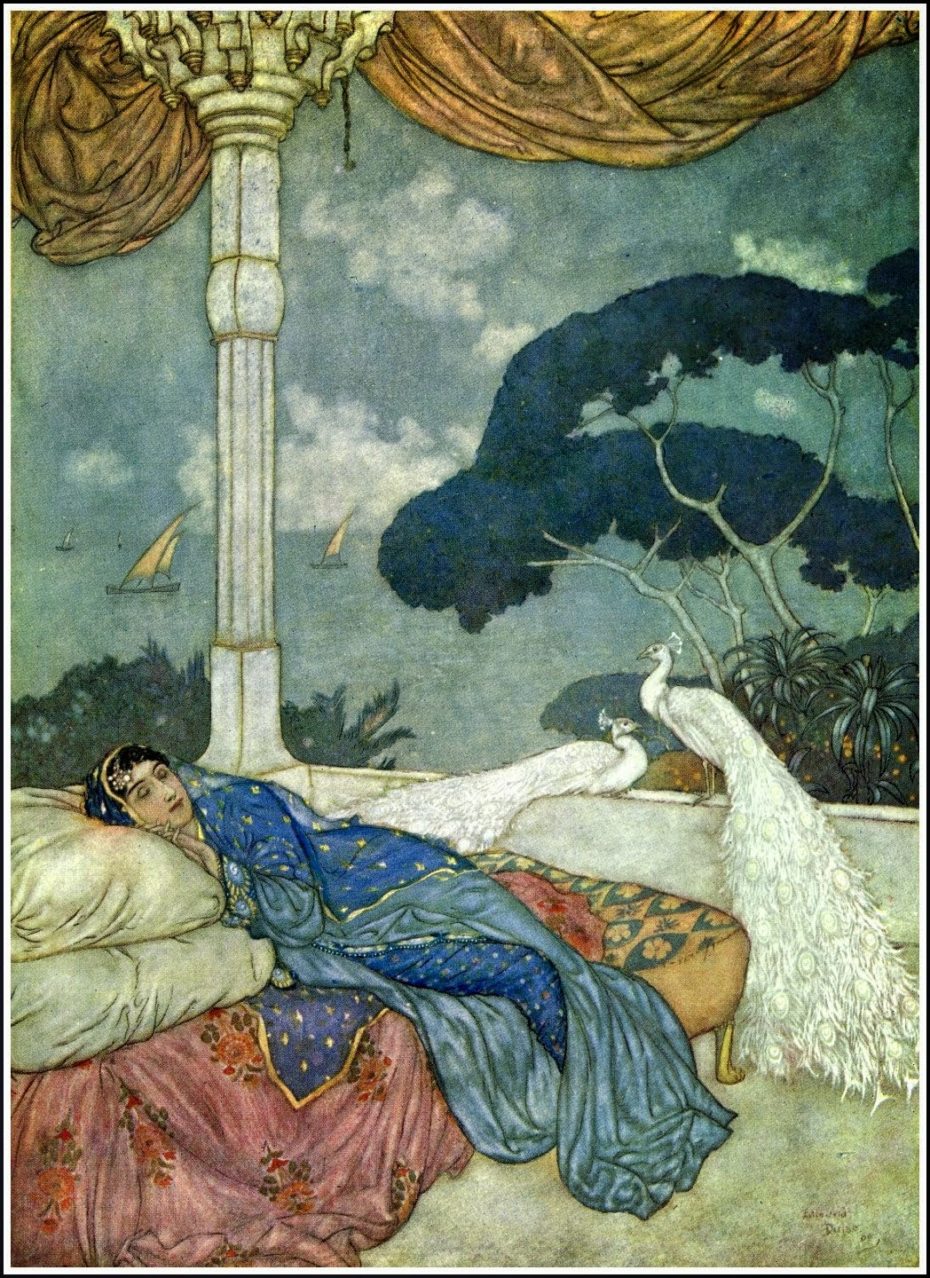

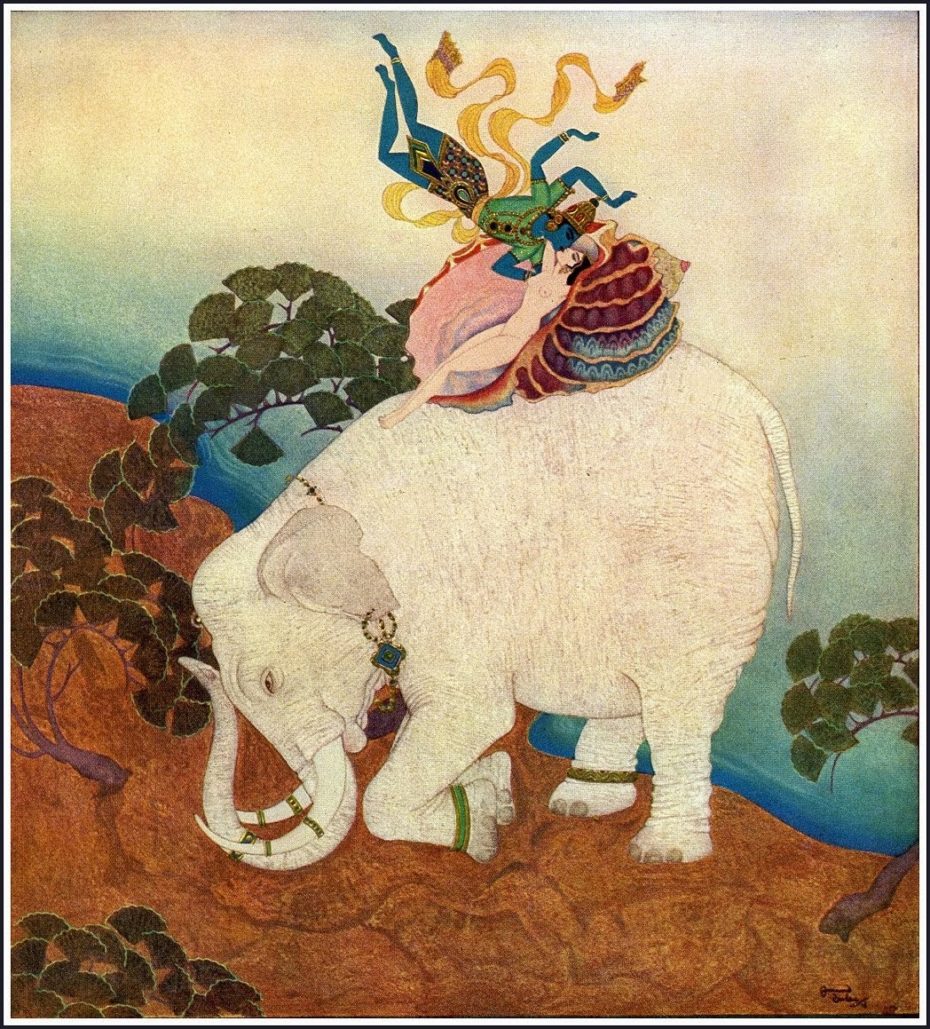

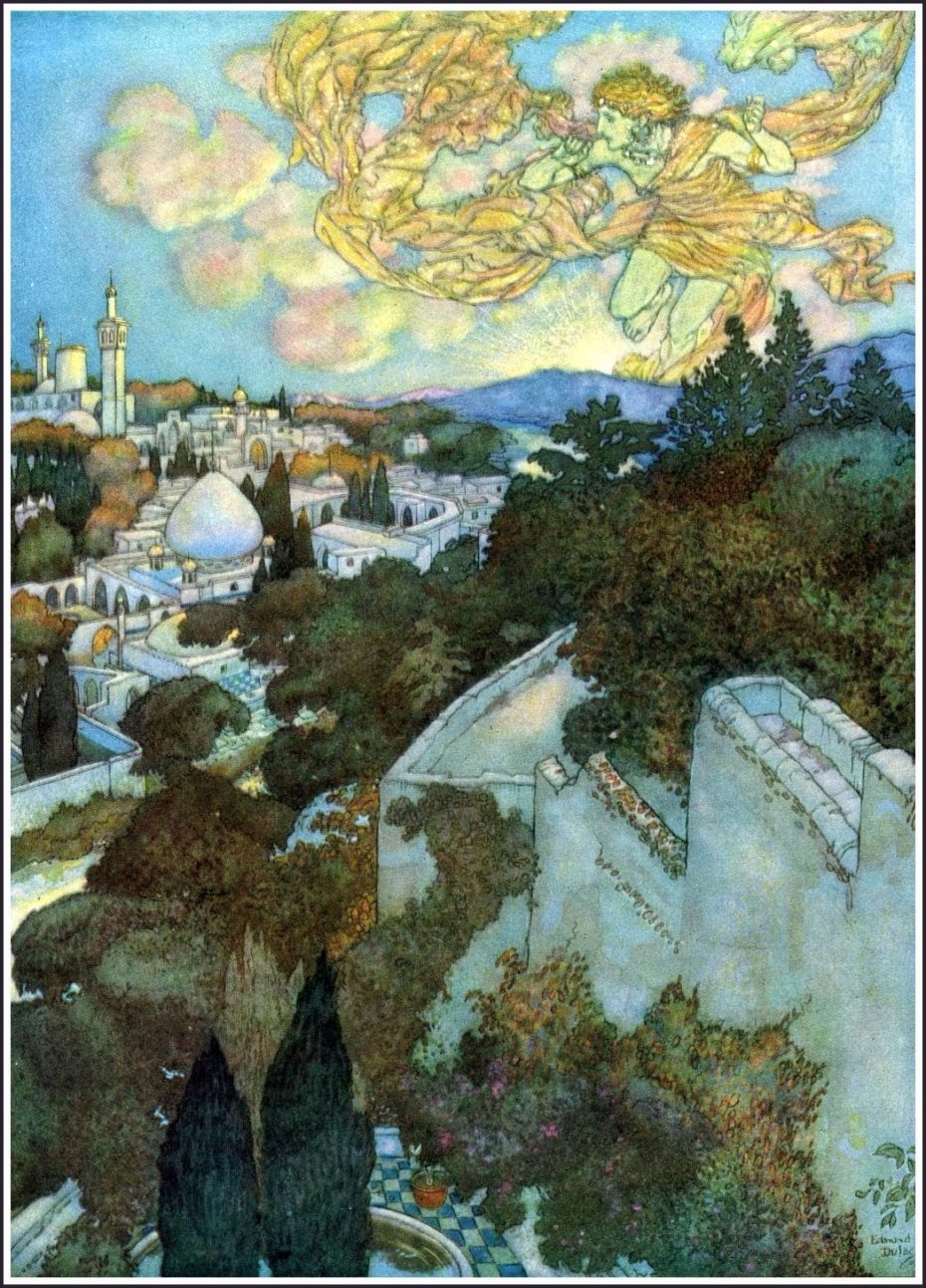

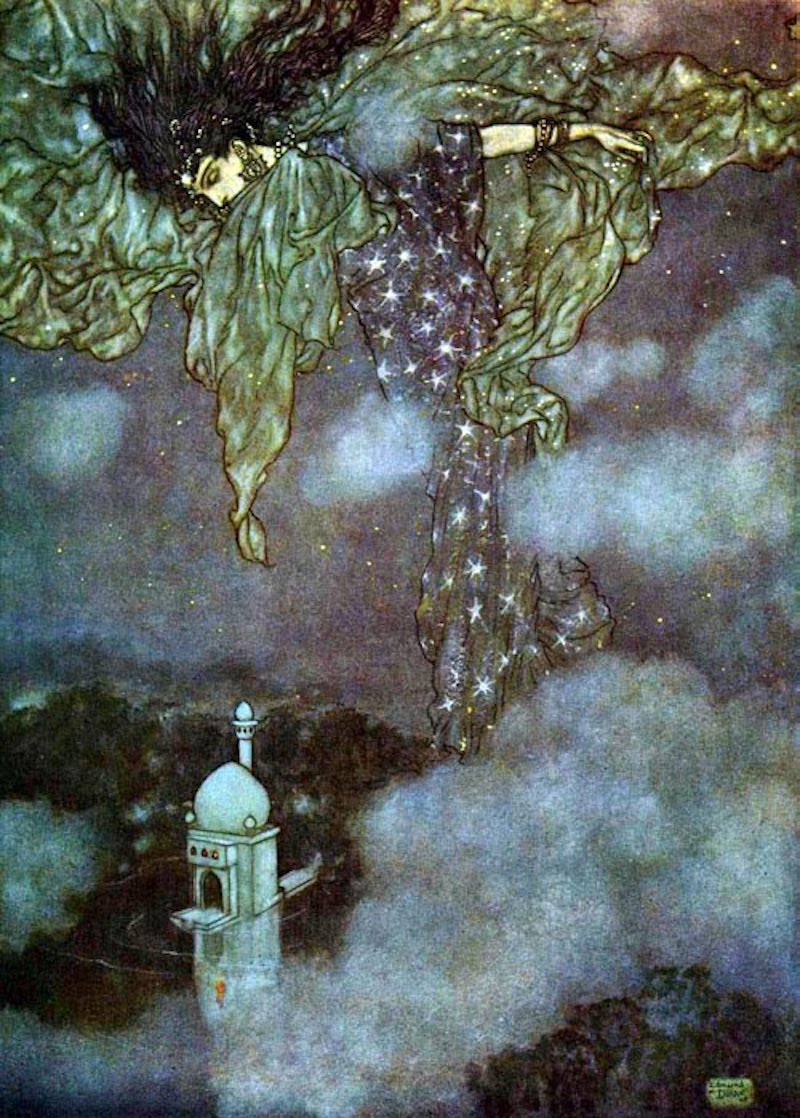

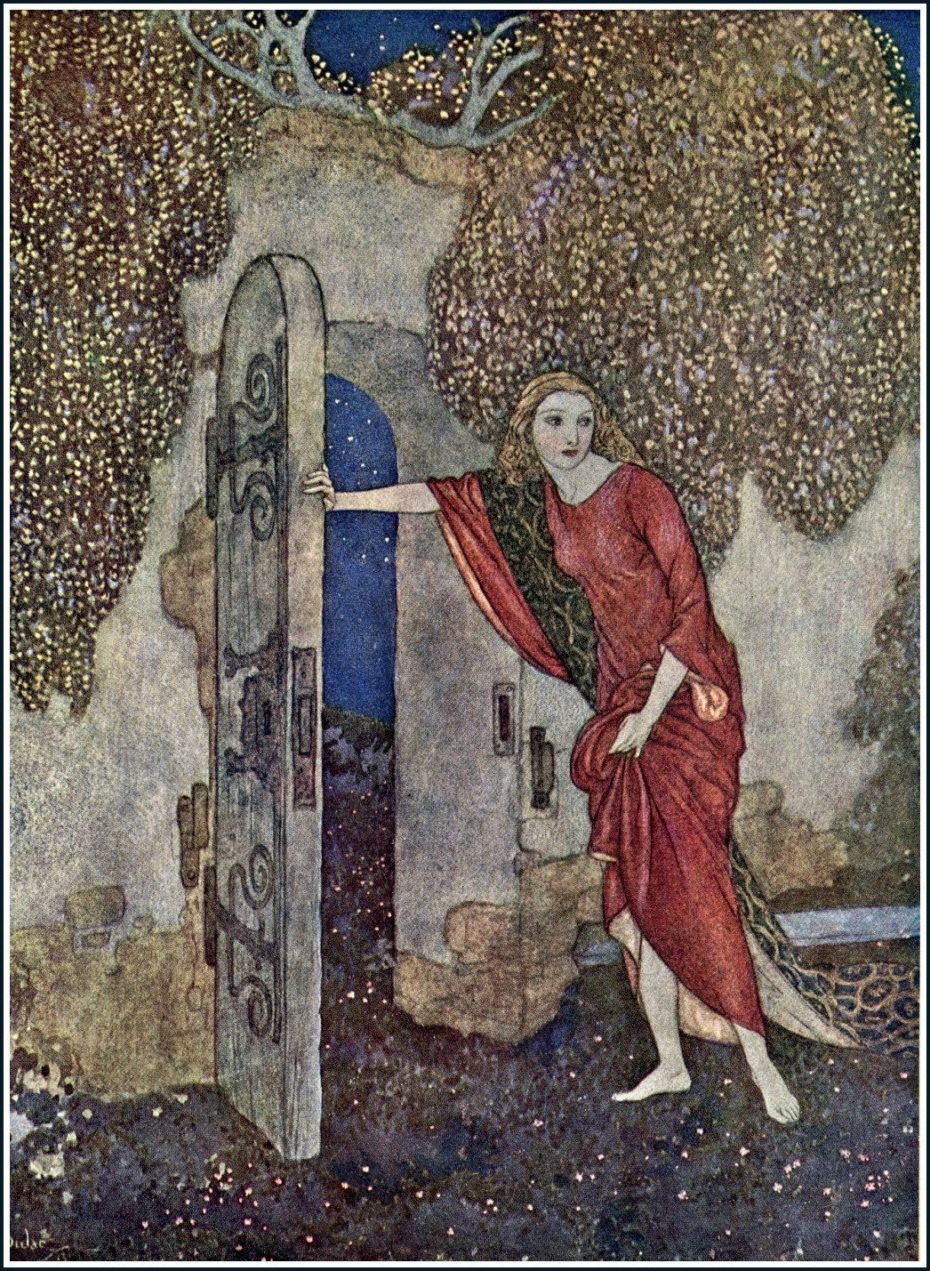

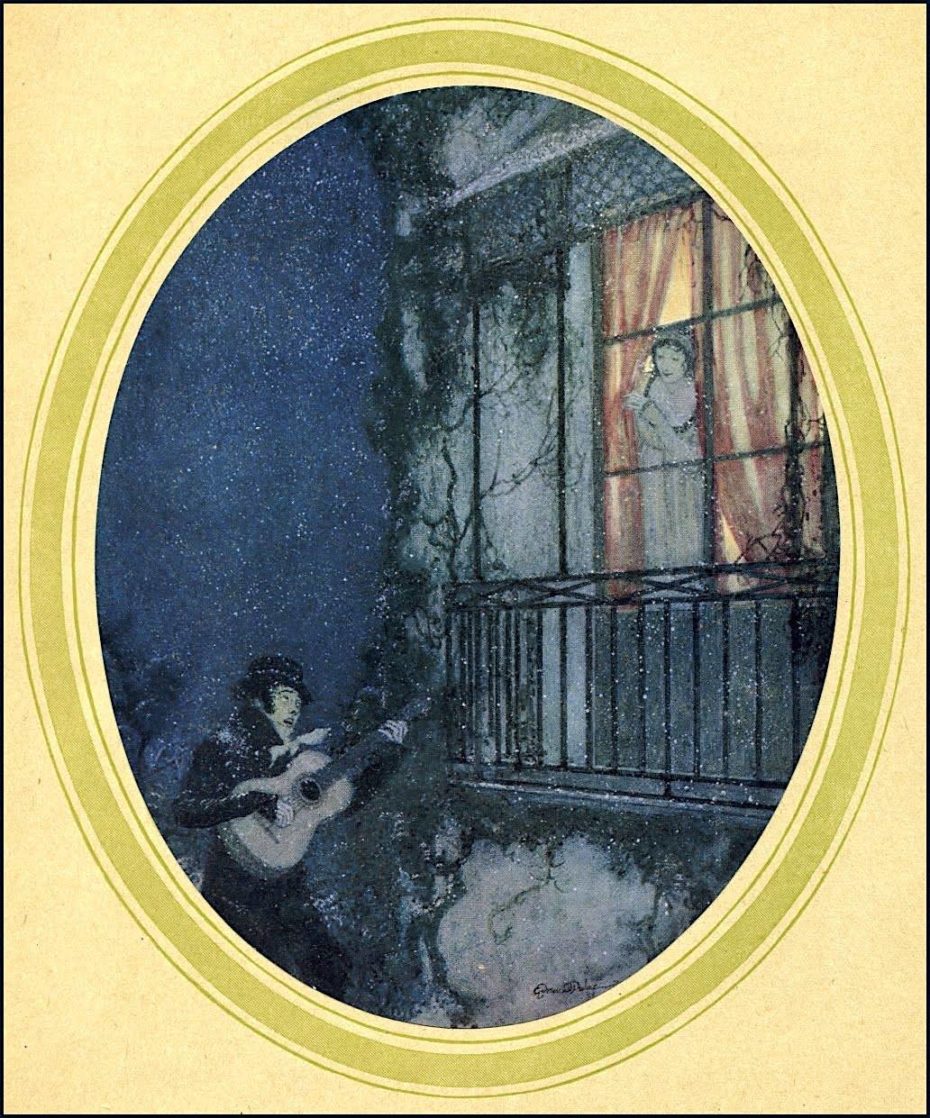

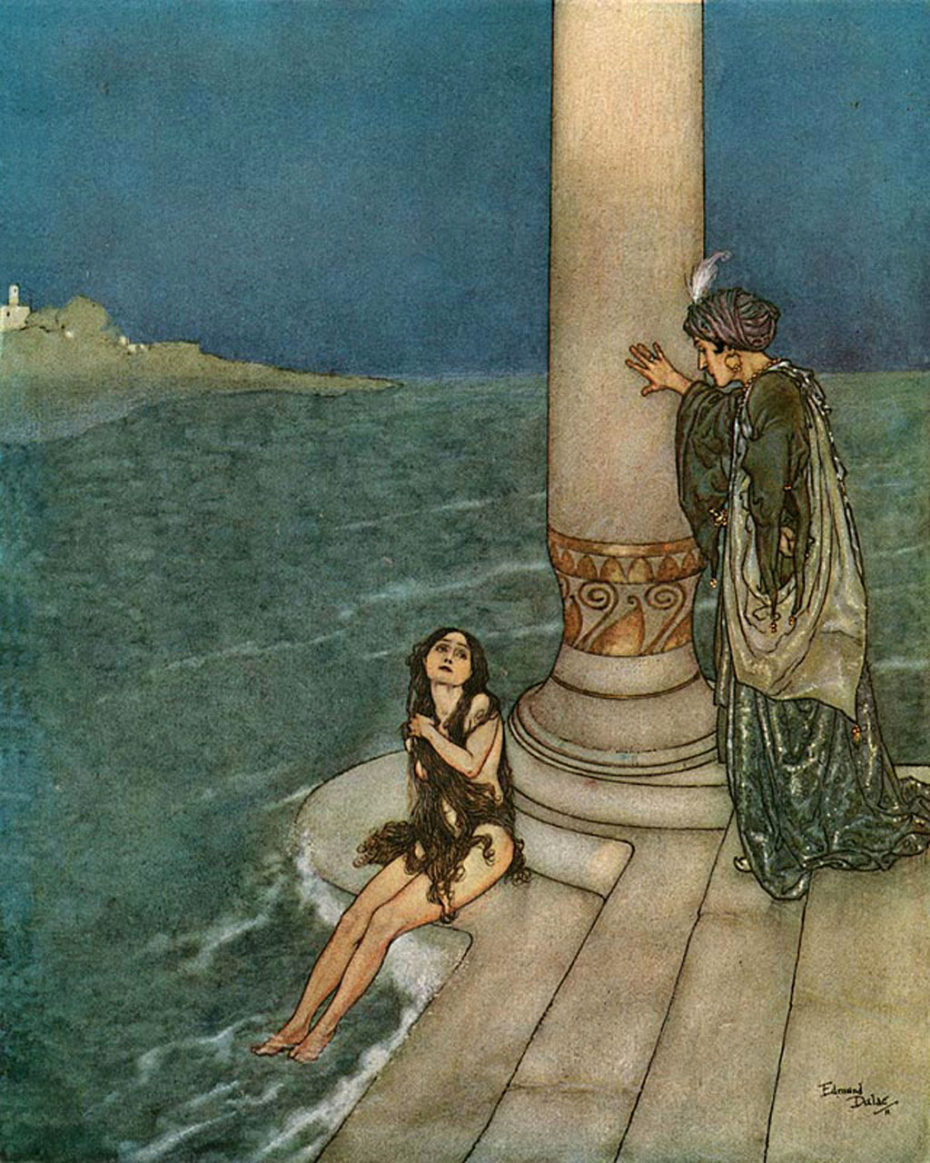

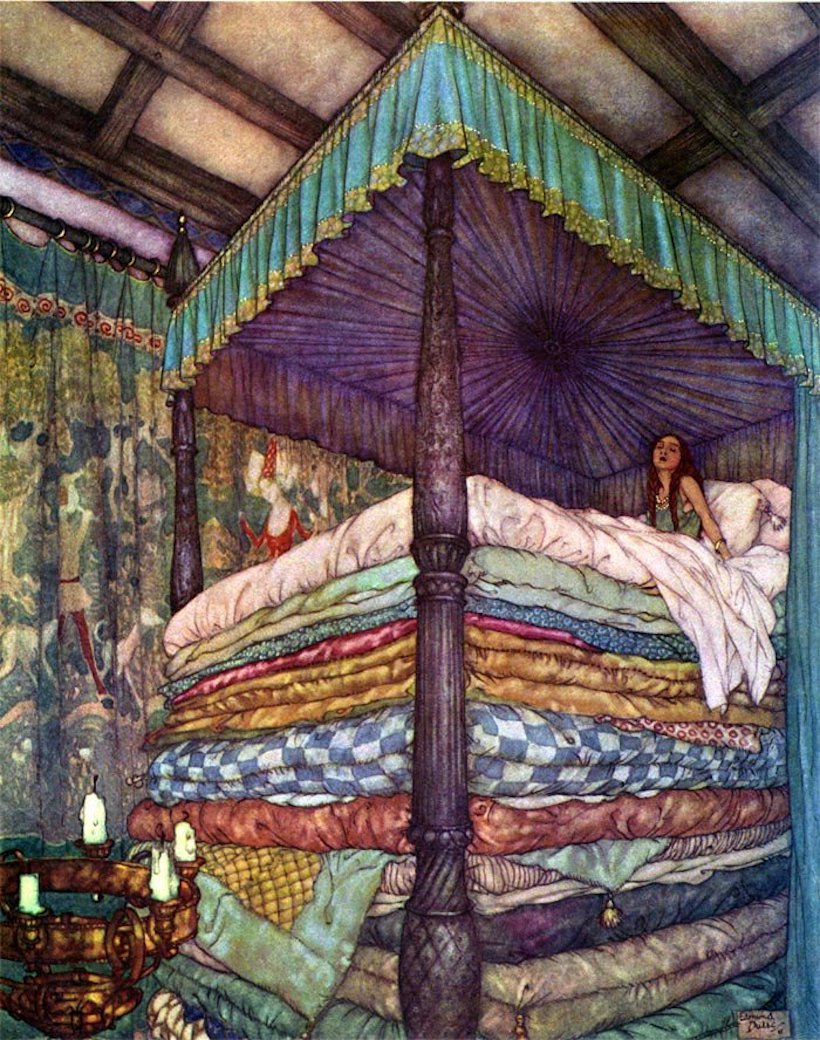

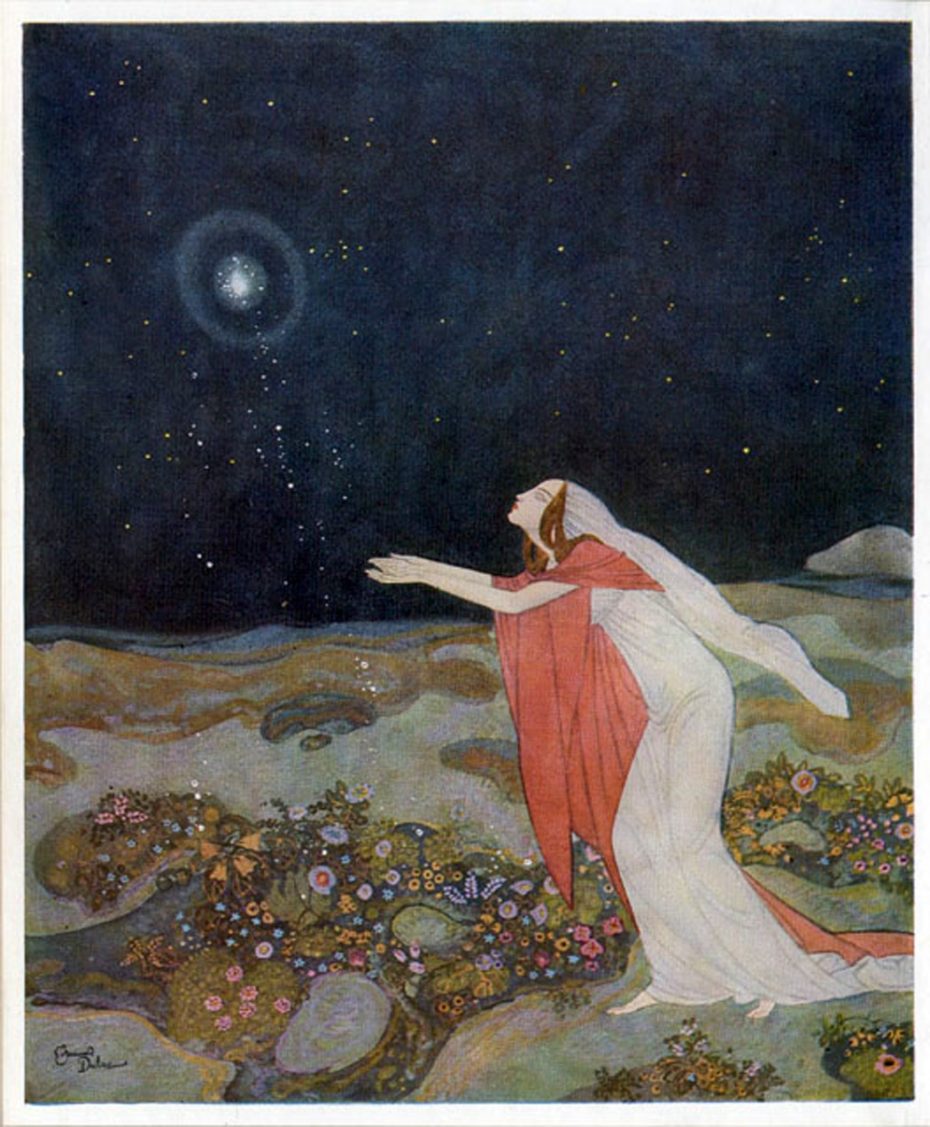

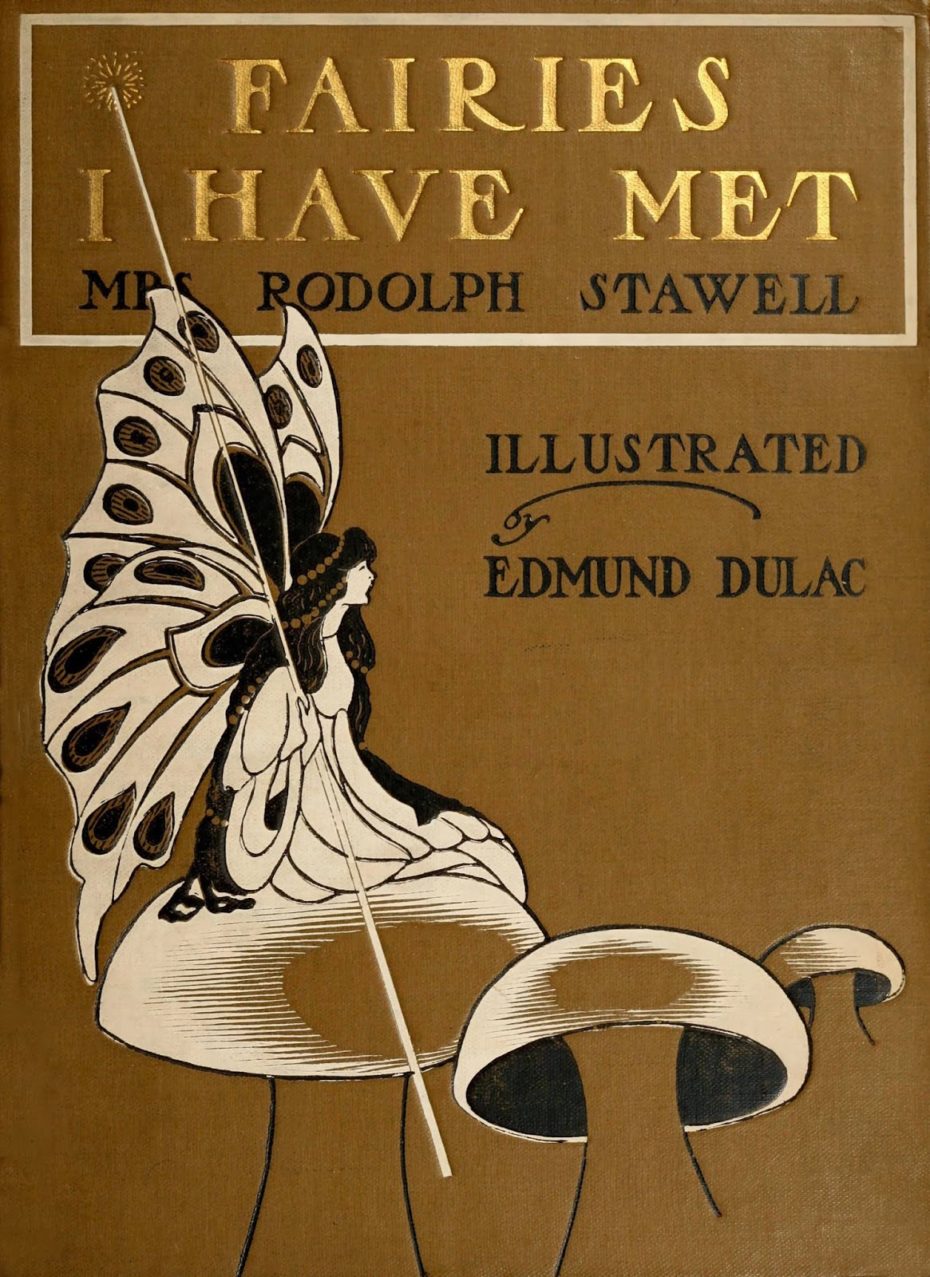

That magical trifecta birthed some beautiful illustrations, from Arabian Nights (1907) to The Tempest (1908); tales by Hans Christen Andersen and Edgar Allan Poe. Like most Art Nouveau illustrators at the time, he also dabbled in tales of the Middle East and Asia with the release of the Persian The Rubaiyat by Omar Khayyam (1909) and Princess Badoura (1913) of Arabian Nights legend.

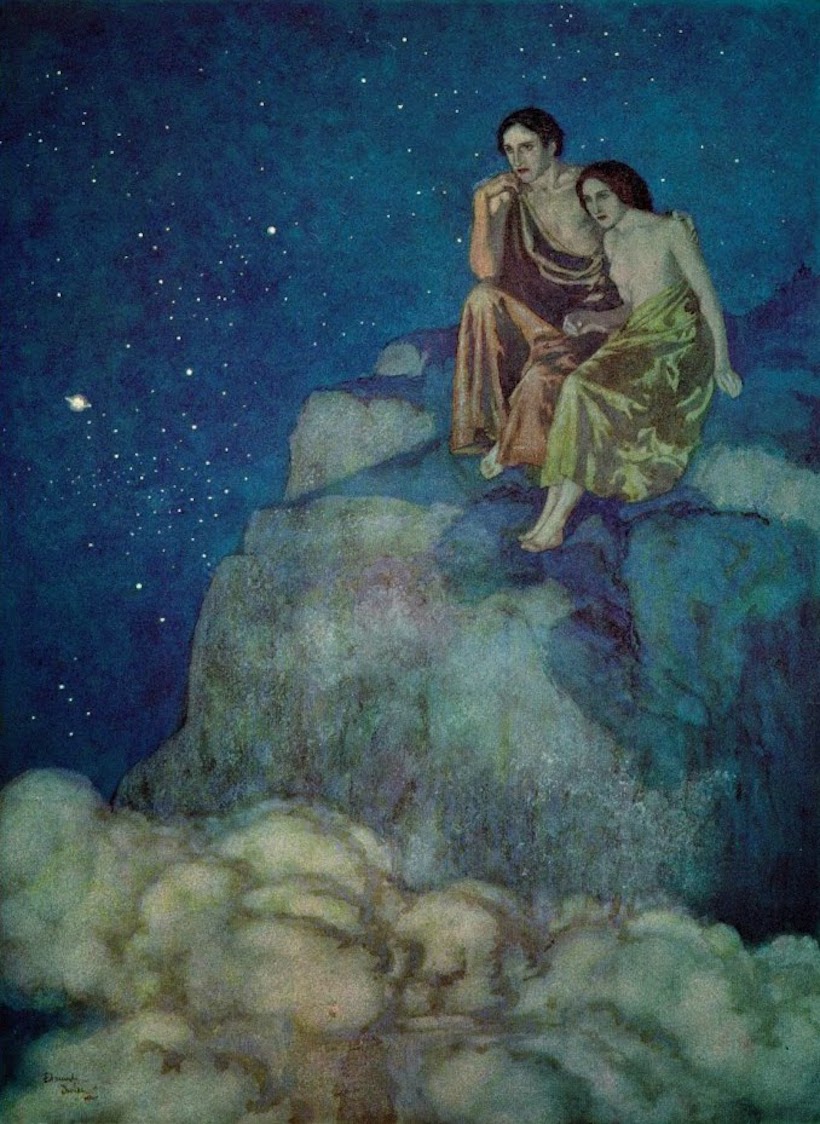

There was both a sumptuousness and levity to his brushstrokes, which were often steeped in a cool or pastel colour palette. This was Art Nouveau: a celebration of intricacy, nature, and escape…

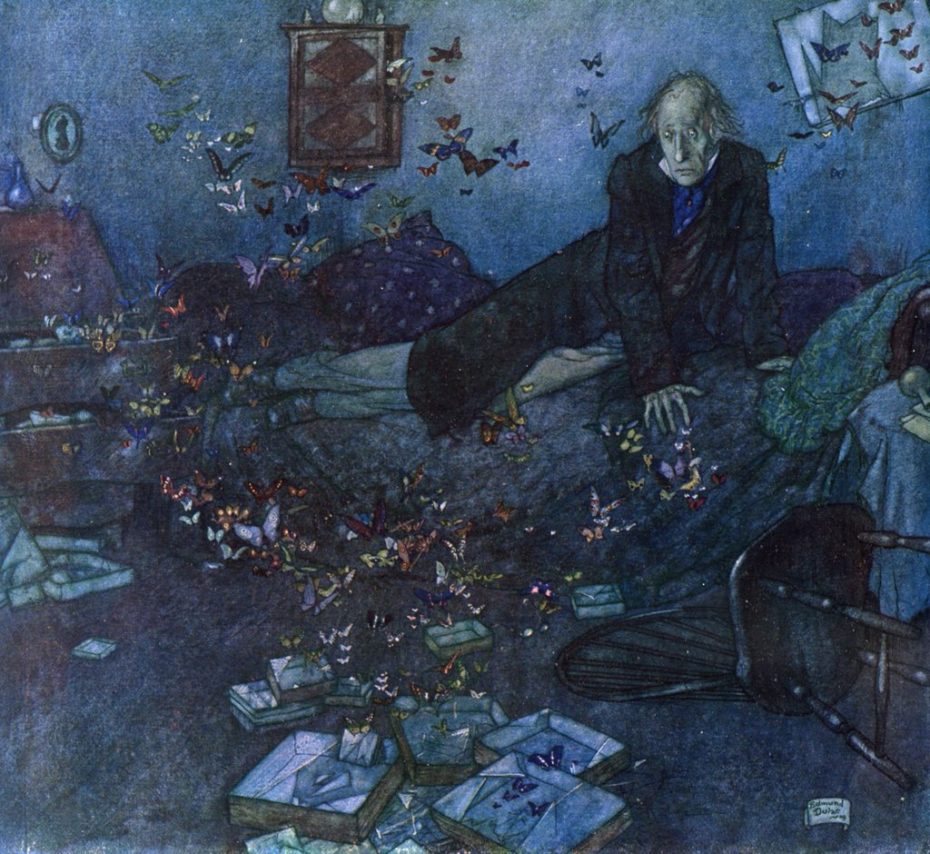

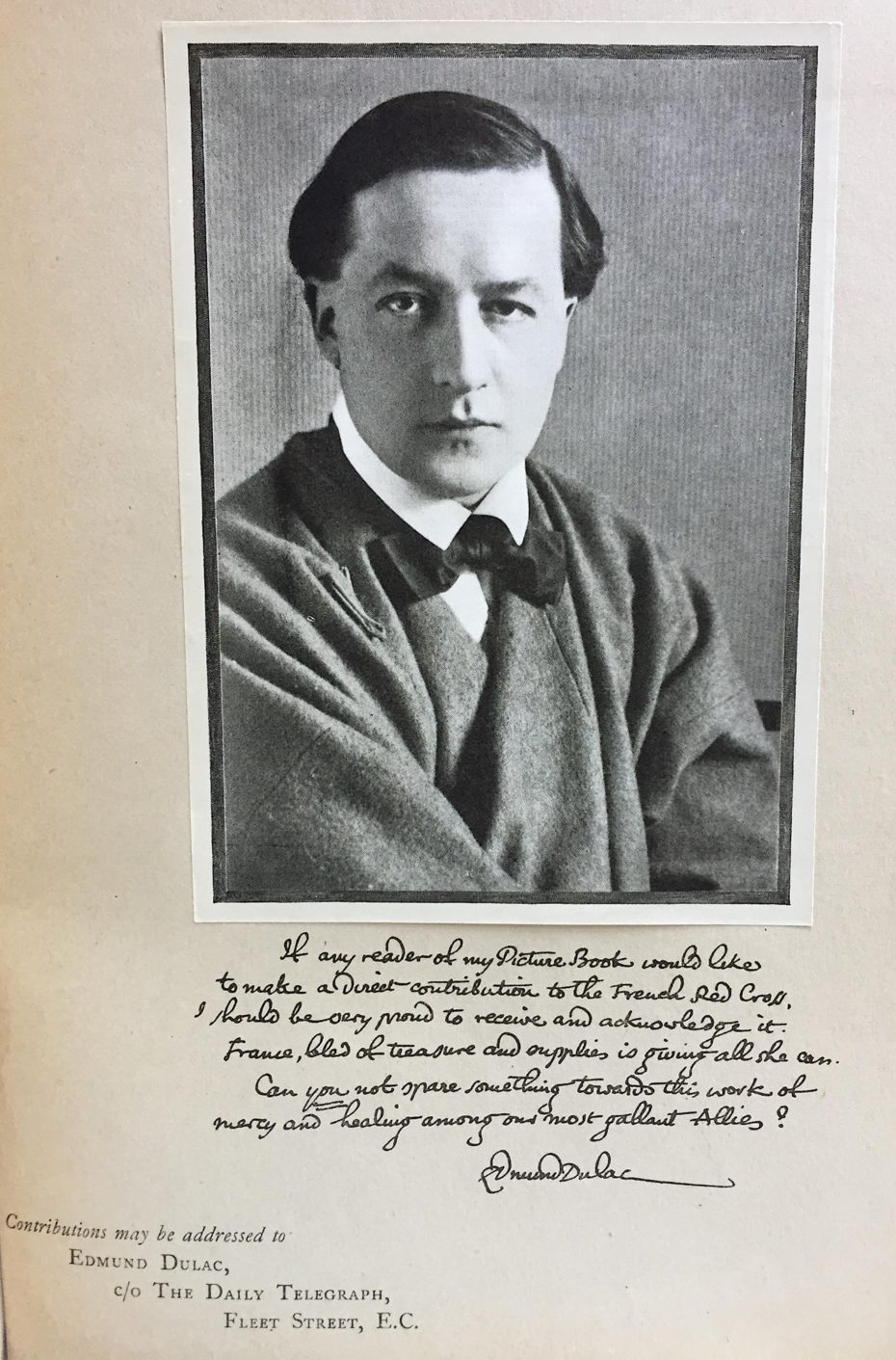

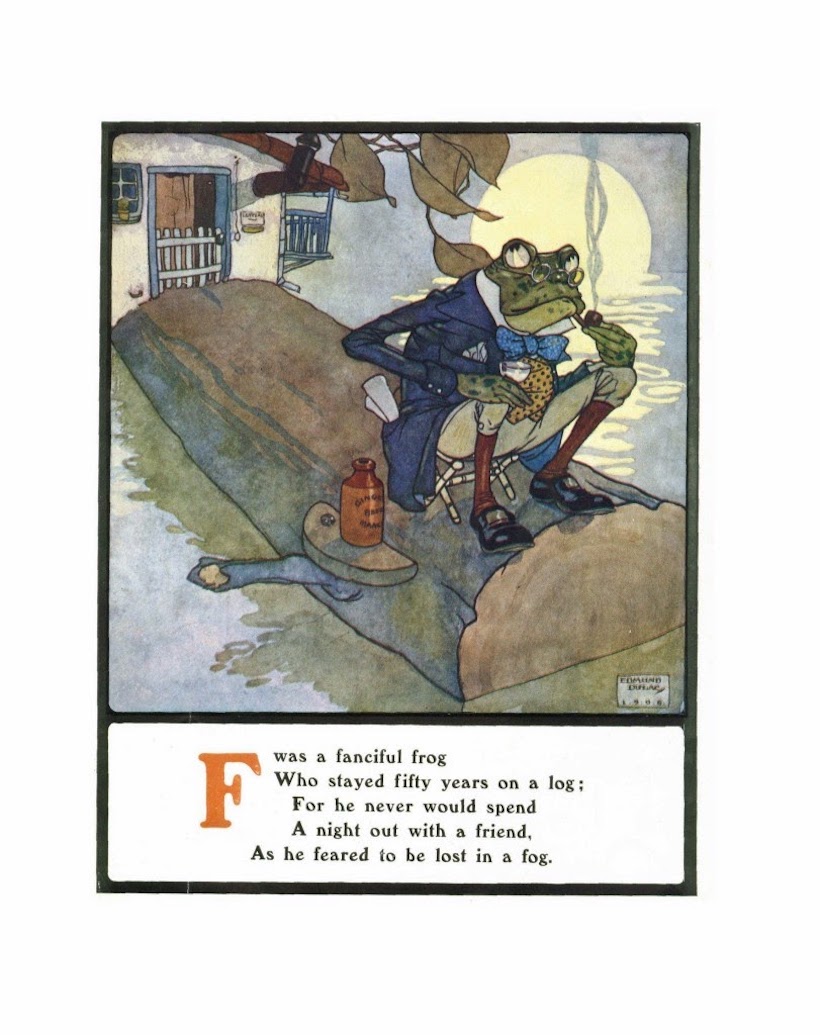

Then came the war, which brought him to a unique career pivot. Dulac was still illustrating for books, but the opulence of the Golden Age was no longer the order of the day; it was time to deliver fantasy on a dollar store budget. He got cracking on more works than ever for magazines, newspaper caricatures, and released Edmund Dulac’s Picture-Book for the French Red Cross (1915), filled with a set of twenty more signature fairytale scenes.

His illustrations served as a refuge from the horrors of the Great War, but he also hoped that books sales could help fundraise for the Allied Cause. Here is a page from “Edmund Dulac’s Picture Book for the Red Cross,” in which the artist makes a heartfelt plea for donations.

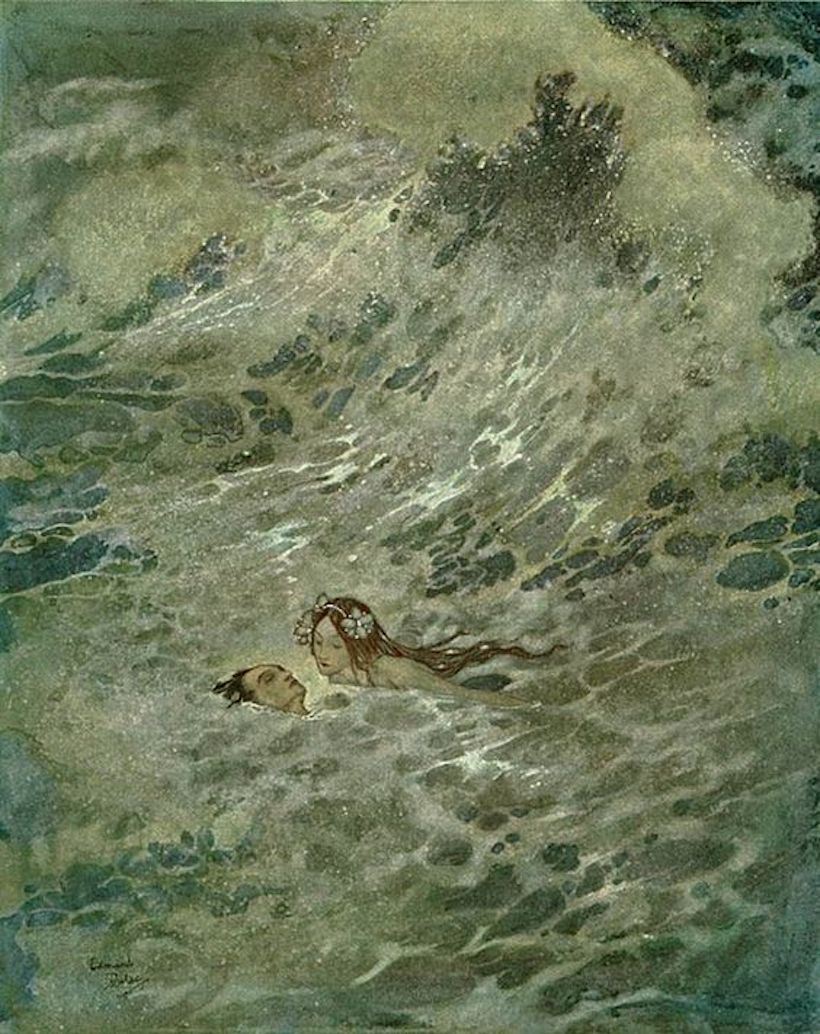

Dulac was a die-hard romantic himself. German-Italian violinist Elsa Bignardi was the love of his life and the model for so many of his most beautiful fairy illustrations. She was his model for the Little Mermaid, and the Princess and the Pea, among others. Dulac himself, a collector of exotic costume, also appeared in some of his own illustrations as the Prince. He and Elsa were very happy together until World War I struck. After witnessing the horror of a Zeppelin being shot down over London in 1916, Elsa, fell into a depression and never recovered. They separated after the war in 1923.

Eventually, Dulac found love again with Helen Beauclerk, a Parisian pianist who was teaching in London. They shared a passion not just for the arts, but astrology and the paranormal, so often depicted in Edmund’s work. Here they are pictured together on their terrace in London:

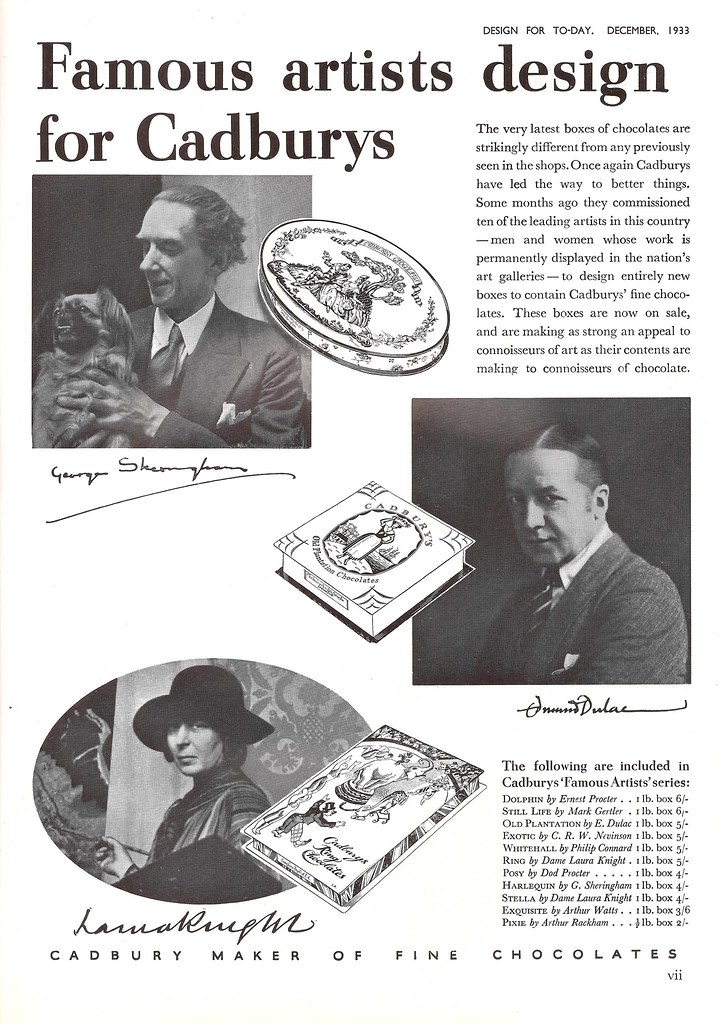

He took on more portraiture commissions, and dabbled in costume and set design for the theatre; he designed medals, bookplates, stamps, chocolate boxes – the list was long, and a testament to his work ethic. Even more so, a reminder of the curious ways we sometimes have to adapt to changing social and economic circumstances (sound familiar?)

Dulac also illustrated for a real-life fairytale queen, Marie of Romania. She became the country’s last queen after refusing a proposal from her cousin, the future King George V of England. Over in Romania, Bram Stoker wrote Dracula, making her adopted country synonymous with vampires and otherworldly folklore. This made Dulac her perfect partner on not one but two children’s books she published, entitled Stealers of Light (1916) and later, Dreamer of Dreams.

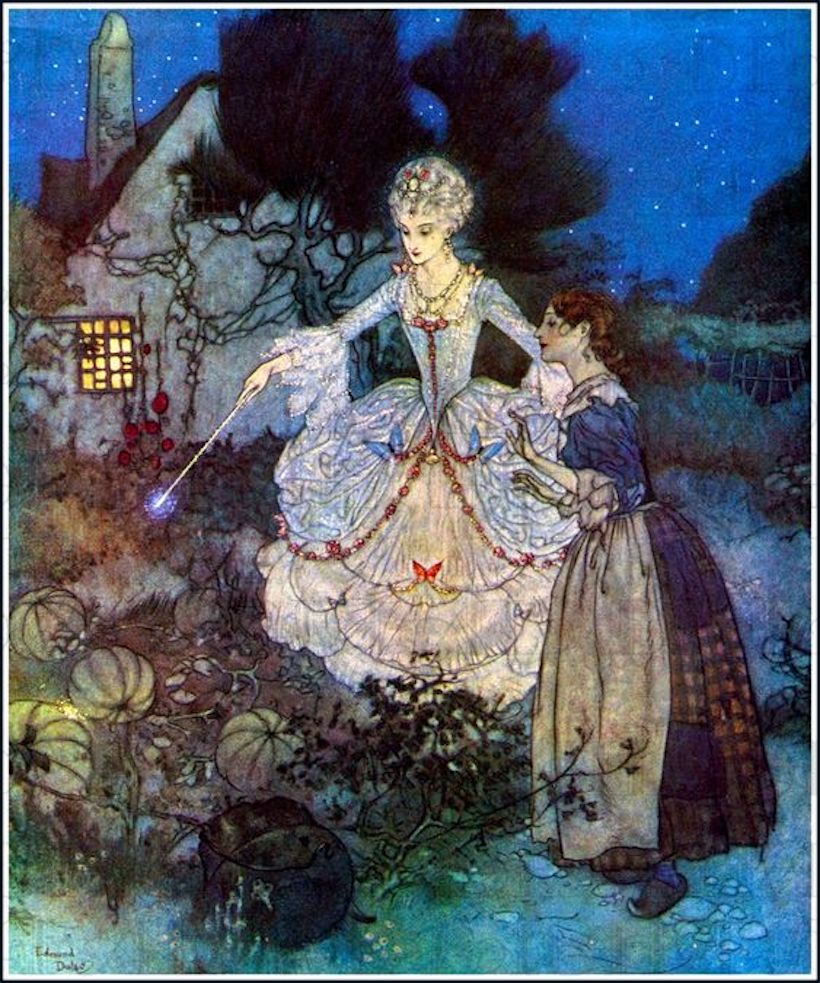

Chèr Journal,

Finished the last illustration for Cendrillon, the English say ‘Cinderella.’ Perhaps the beautiful tale of magic and love will serve to take the minds of young and old alike off the horrors of this war. I gave the Fairy a butterfly dress, I wonder if children will notice?”

Edmund Dulac. January, 1915

Ever committed to creating, it’s rumoured that Dulac passed away mid-illustration in 1953 for Comus, a Mask by John Milton, which scholars regard as his “first dramatising of his great theme, the conflict of good and evil.” The other rumour is that Dulac suffered a heart attack following “a strenuous bout of flamenco dancing”. What was left behind is thousands of works of art and dazzling design ahead of its time, in all shapes, sizes and mediums.

“L’art, c’est la liberté…”

Edmund Dulac, 1900

If you’re ever in a rare book store, look out for the name: Edmund Dulac. You’re in for a treat (and a very good investment).

In the meantime, browse an extensive online collection of his work here.