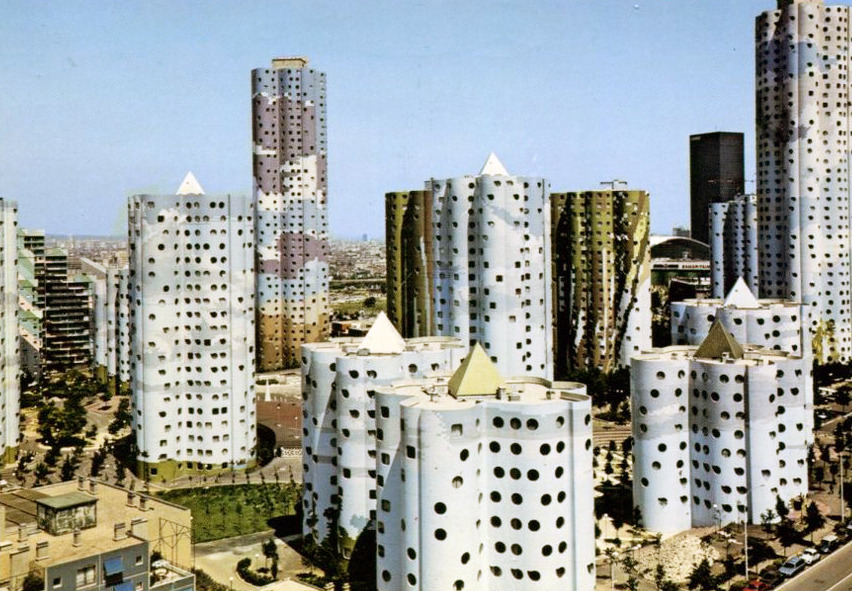

Ah, la douce France! Cobblestone streets and cafés lost in time, quaint little ancient villages surrounded by vineyards, heart-achingly beautiful architecture and skylines, just like you’ve seen it in the movies. Right? Well sure, but that’s only half of the story. Sometimes, France can look like the Eastern Bloc. Sometimes, it can look like the utopian post-war architects had an absolute field day with “2 for 1” deals on concrete.

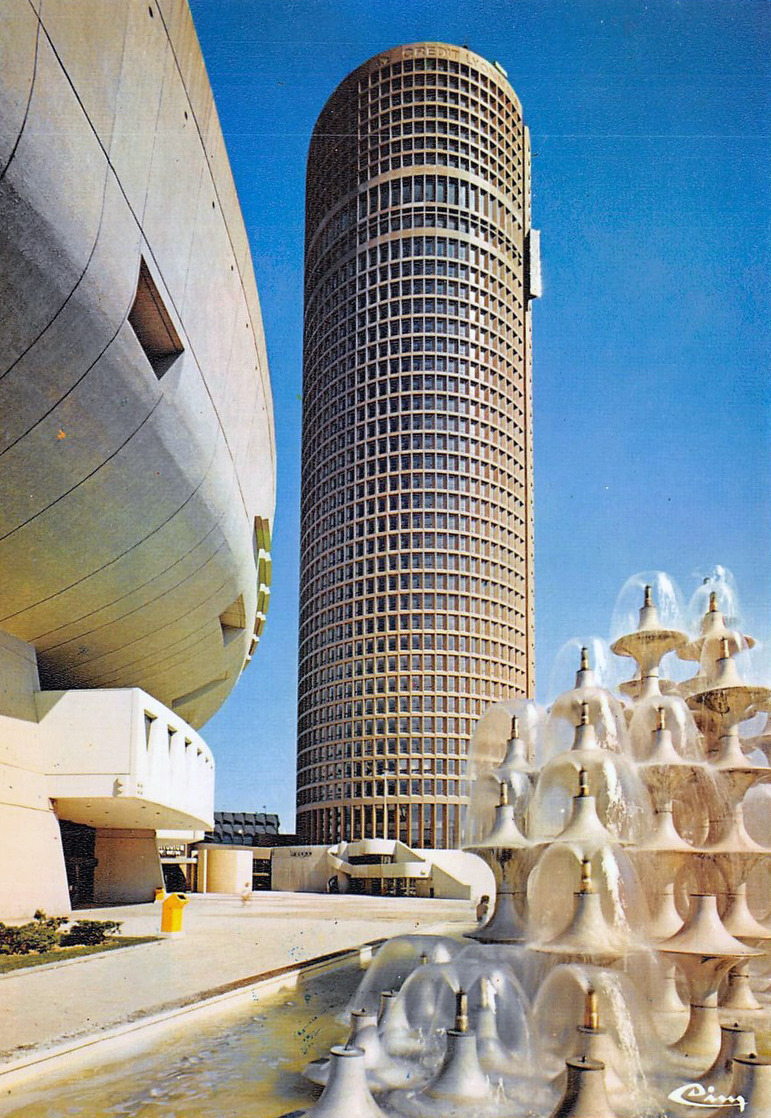

It’s easy to forget that Brutalism was pioneered by a French architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, or “Le Corbursier,” and that a lot of French people thought it was a very good idea to build these hulking monoliths of cement all over the country.

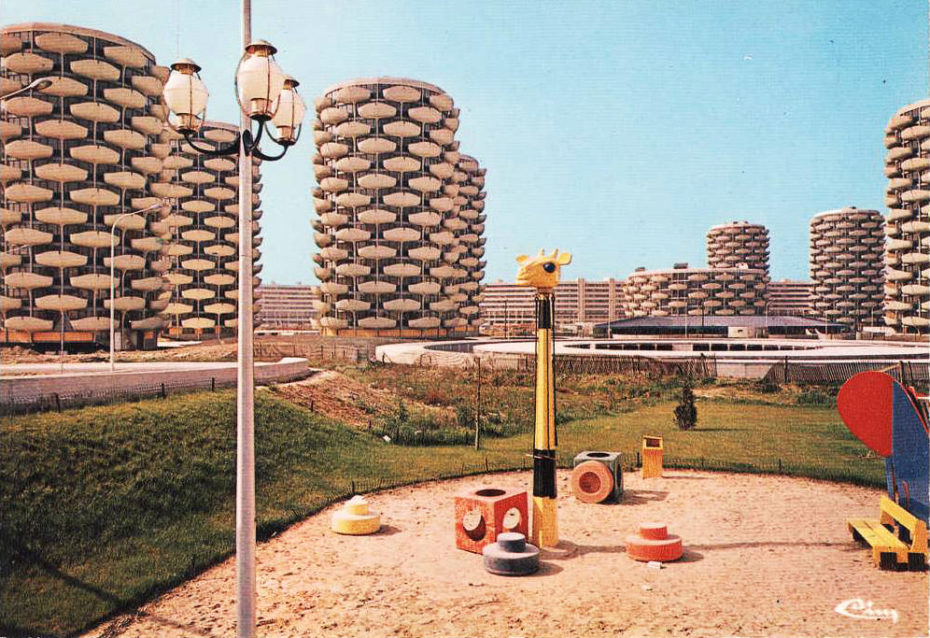

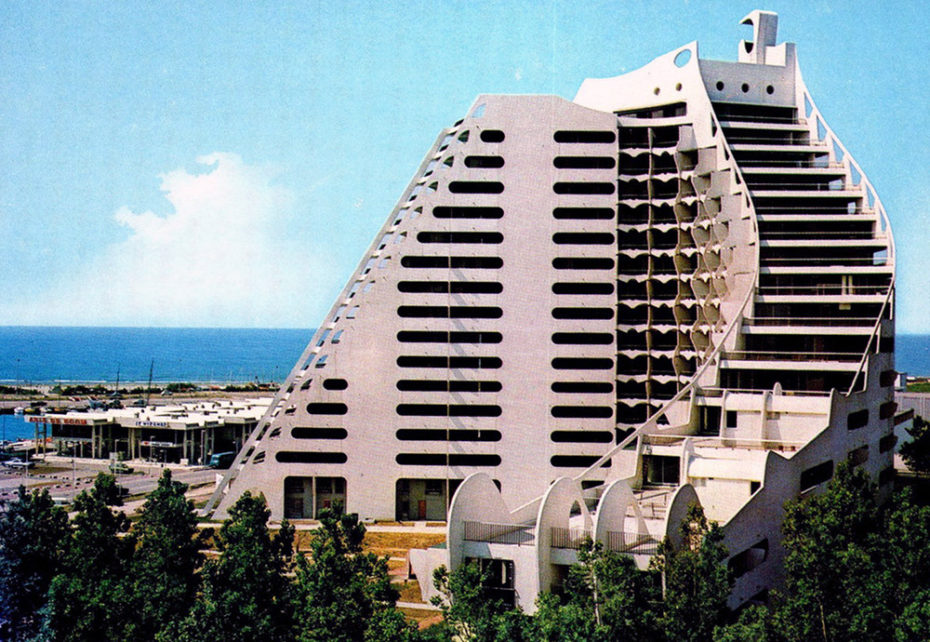

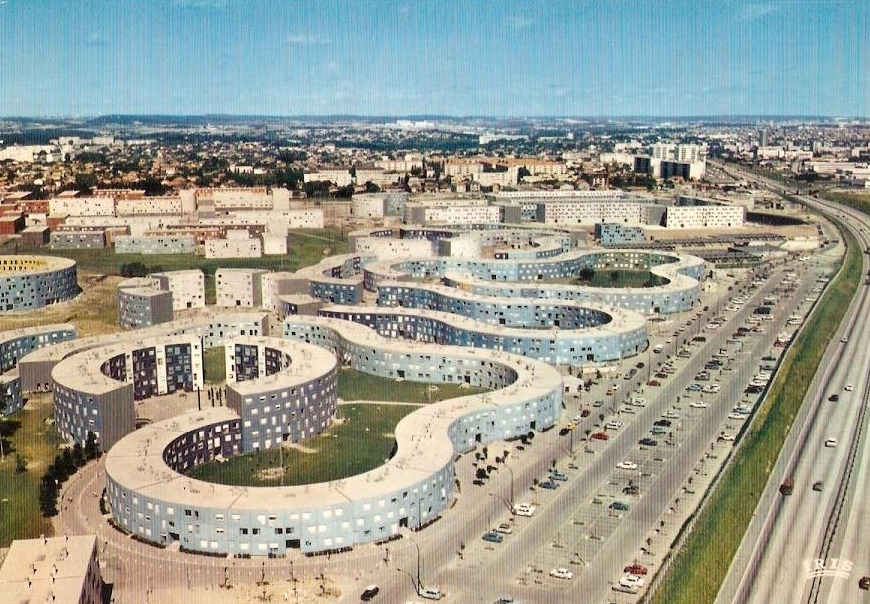

There’s the concrete holiday haven of La Grande-Motte, a Modernist time capsule seaside resort of gleaming white concrete pyramids by architect Jean Balladur, who dedicated 30 years of his life to the project, which was completed in the ’70s.

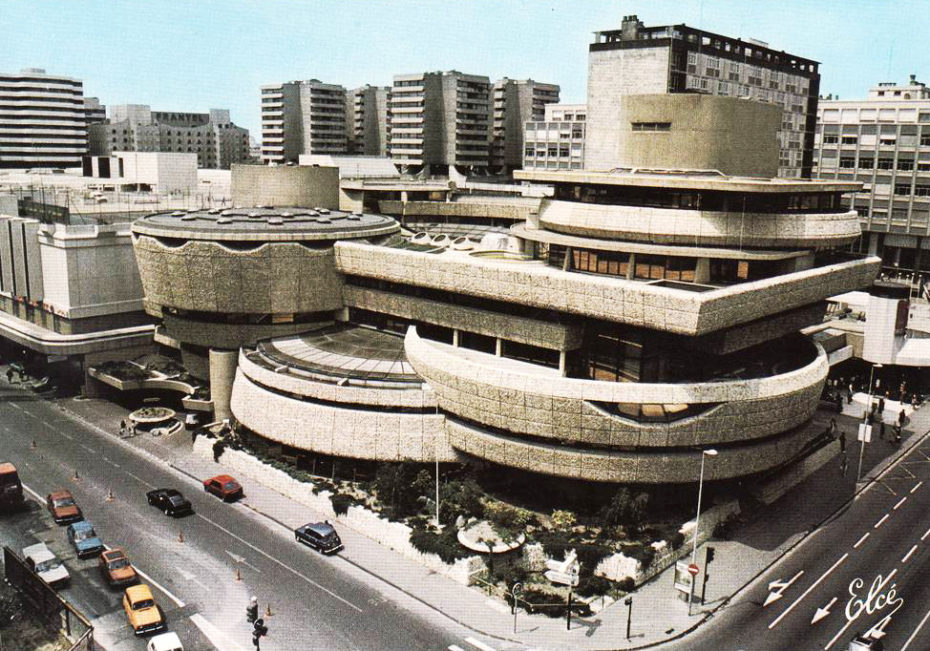

In the suburbs of Paris, we have the “Choux de Créteil,” a utopian village of concrete cabbages, as well as Ricardo Bofill’s infamous Espace d’Abraxas, used as a dystopian film set in Brazil (1985) and the Hunger Games trilogy. Even Paris itself has a Brutalist side, most notably in the 12th and 19th arrondissements.

Like it or not, Brutalist and Modernist architecture is as much part of French (and global) history as the gargoyled churches and Haussmann-lined avenues. And it tells a compelling story, albeit one that’s not always easy to see today under decades of dirt, disdain and neglect.

As you might be able to tell, I’ve come across an archive of vintage French architecture like no other. You think you know what France looks like until you’ve had a good rummage through Retro-Geographie, a little corner of the internet that would argue, convincingly, that France was the true home of Modernism.

If you told me 10 years ago that I would one day be making a case for the preservation of Brutalist or Modernist architecture, I would have put money on you being wrong. And to be honest, I’m still trying to get to grips with learning to appreciate it. So much of it can be awful. And so much of it did go up in place of precious and historic architecture reduced to piles of rubble during war.

As one of architecture’s most divisive styles, branded “cold-hearted,” “inhuman” and “monstrous,” Brutalism has a reputation that’s hard to shake. When so many of these buildings were used as authoritarian government facilities, such as council offices, police stations, prisons, public schools, hospital wards and public housing, it’s hard not to imagine them as covert emissaries in a totalitarian or communist regime. Not to mention, so many of them have aged poorly in damper climates.

Yes, all of that’s true. But what is the alternative? More glass boxes for our skyline instead? To continue demolishing buildings before they reach the ripe age of 50?

Architect and architectural historian Michael Kubo reminds us that it wouldn’t be the first time we vilify buildings once they’re no longer new, and cutting-edge, but not quite old enough to be worthy of our respect.

In speaking to the Washington Post, Kubo brings up the example of Victorian architecture; how much of it was once “regarded with embarrassment,” quoting a British humorist writer in the 1930s on the subject:

Whatever may be said in favour of the Victorians, it is pretty generally admitted that few of them were to be trusted within reach of a trowel and a pile of bricks…”

P.G. Wodehouse wrote in 1937, (via the Washington Post)

Nowadays, we’re horrified to hear about Victorian architecture being sentenced to the wrecking ball, and of course so much of it was tragically lost to overzealous city planners in the 20th century.

French comic Jacques Tati famously poked fun at postwar Modernism in in films like Mon Oncle (1958), detailing society’s relationship with this strange, “pretentious” new architecture that was encroaching upon older parts of Paris. Design he called, “so geometric as to have lost any human or inhabitable character.”

But speaking to The Financial Times, professor of architecture and urban culture Iain Borden says that, “although Tati’s cinema is critical of the Modernist aesthetic, design is cast in a positive light.

“The house in Mon Oncle is a suburban bourgeois villa, critiqued for its American consumerism, faintly ridiculous design and pervasive middle-class values,” he says, “but it is still a welcoming, appealing kind of house.”

Iaian Borden, speaking to the FT

In fact, watching back Tati’s Mon Oncle is a visual treat, allowing the viewer to appreciate both the charm of historic “old” Paris, as well as the exciting designs of the Modernist aesthetic.

There is a growing case for Brutalist architecture, already underway for Modernist architecture, not just to preserve it, but repurpose it.

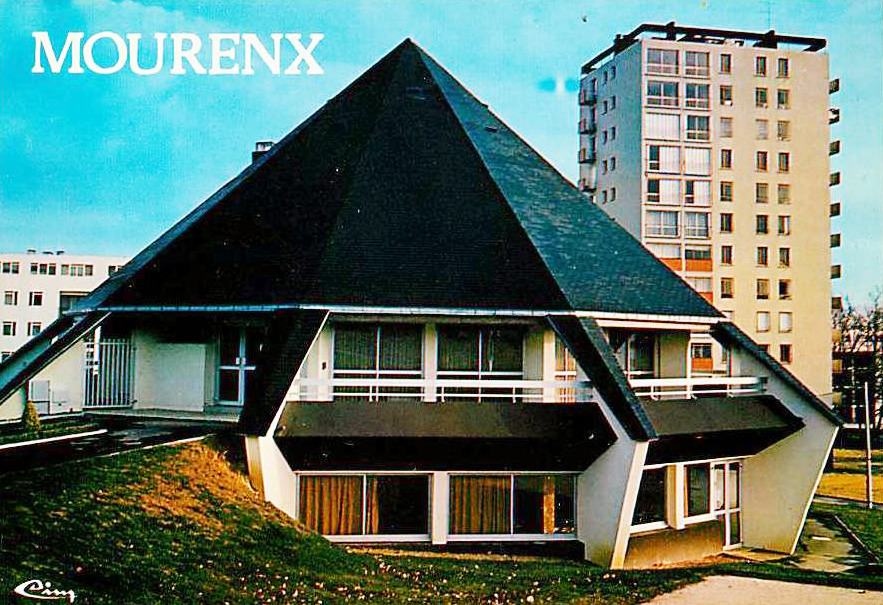

Archi: André Dubreuil et Roger Hummel. Prix de Rome. 1969.

Who’s to say we can’t bring these buildings back with a pop of colour, an upgrade to the finishes, retro interiors, and a revival of groovy graphic signage?

These 20th century photographs and postcards make it all look positively picturesque. Dreamy, even. Could it be possible that some inexpensive renovations might bring some of that back? In lieu of bulldozing them and rebuilding at great expense, are they not the perfect canvas for experimentation?

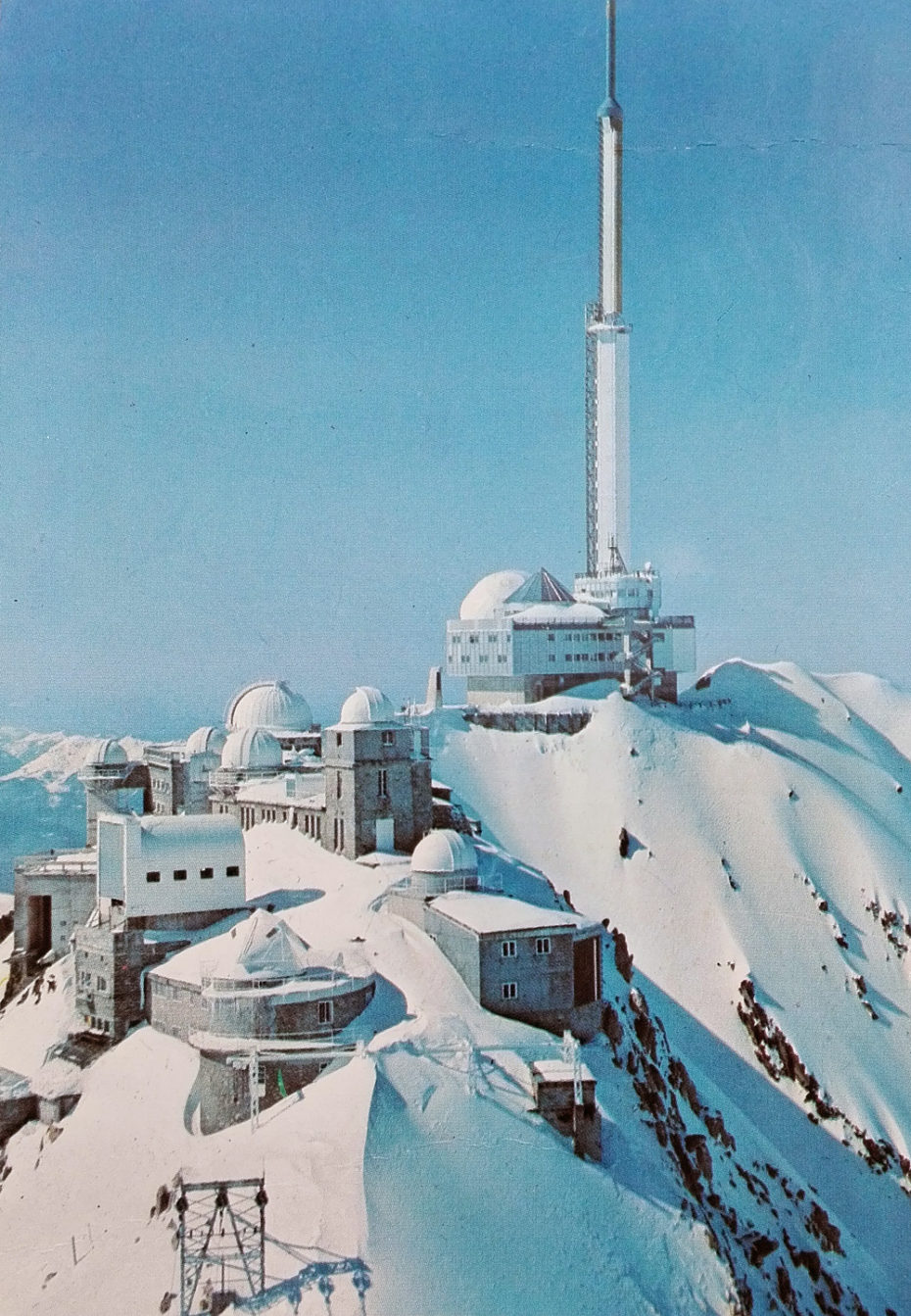

It’s so easy to miss and dismiss as cold and depressing, anonymous architecture. But take another look. There is a story here for everyone. In one light, these buildings capture our innocence and optimism, from a moment in time when we liked to believe we were already living in the future world on the verge of living in space with colonies on Mars. They also remind us of our darker side, of how easily humanity can lose its way, but also of our ability to overcome adversity and hardship.

So I do hope this compendium of Brutalist and anonymous Modernist architecture (that you didn’t ask for) might prompt some of us to re-evaluate the visual appeal of these buildings. After all, finding the beauty in the ugly is always a healthy exercise.

Browse more French Brutalism and Modernism on Retro-Geographie.