On any given night in 1970, a teen somewhere in rural America could dial a number and hear the radical wisdom of Patti Smith, John Cage, Allen Ginsberg, William S. Bourroughs – the list of poets was long, and painfully hip. One needed only the ten sacred digits of “Dial-a-Poem,” a revolutionary hotline that connected millions of people to a room of telephones, linked up to an evolving selection of live-recorded poems, speeches, and inspired orations. And frankly, we’d kill to dial up that hotline right now…

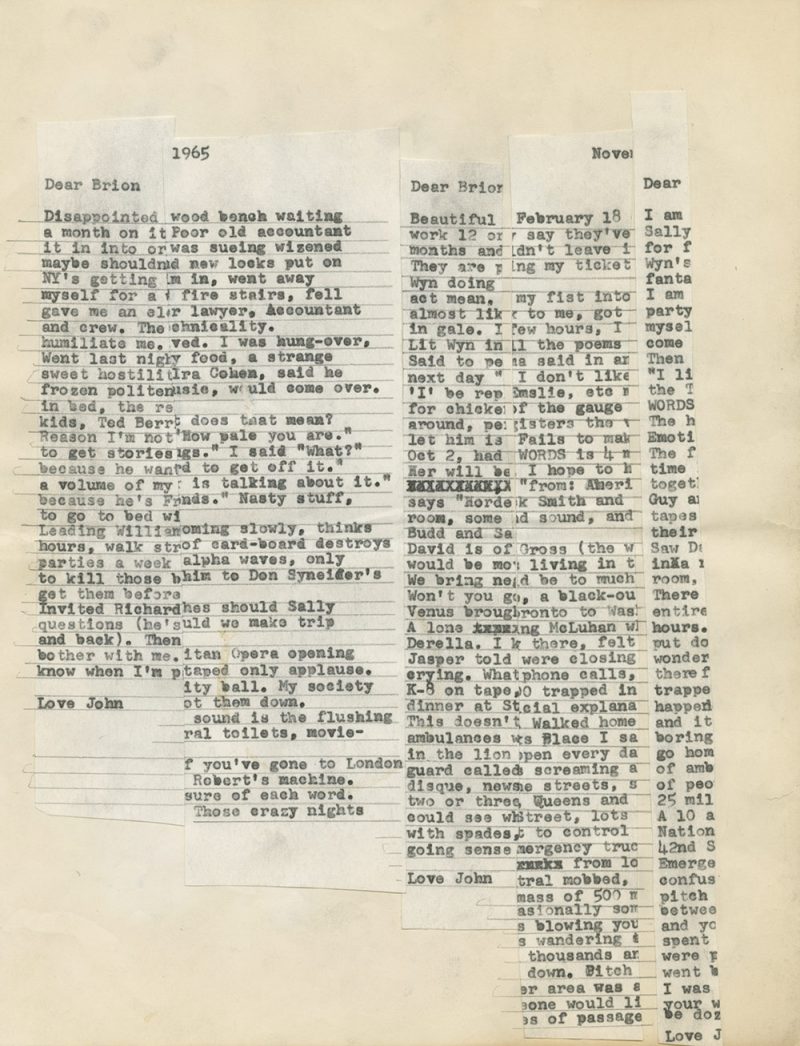

It all began in the 3rd floor Manhattan loft of the hotline’s founder, artist, and activist, John Giorno, who also happened to be Andy Warhol’s lover at the time. John was on the phone one morning with someone and feeling cranky. “I was probably crashing from drugs and had a hangover”, Giorno remembers in an archive BBC documentary. Wishing he didn’t have to listen to an irritating voice at the other end of the line, he wondered to himself: what if he could listen to a voice reciting a poem instead?

Now this might not sound like such a radical notion, but in 1969, it really was. Before the internet (with its Youtube recordings at the click of a button), if you wanted to hear poetry spoken aloud, and you weren’t anywhere near a big city or a burgeoning counter culture scene – let’s just say your options were limited. This was an idea that could make poetry, or anything for that matter, accessible to millions of fans.

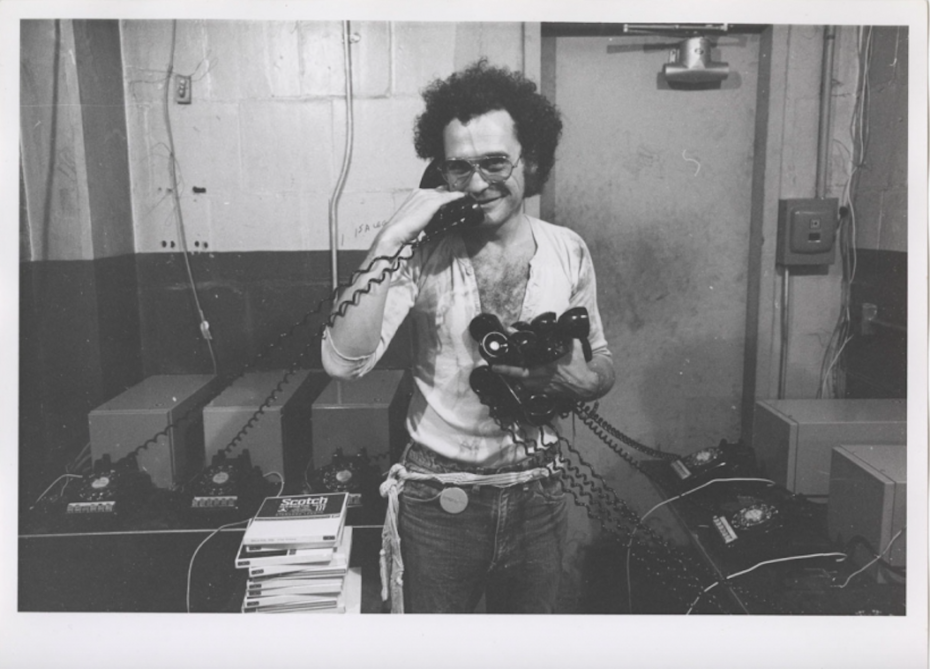

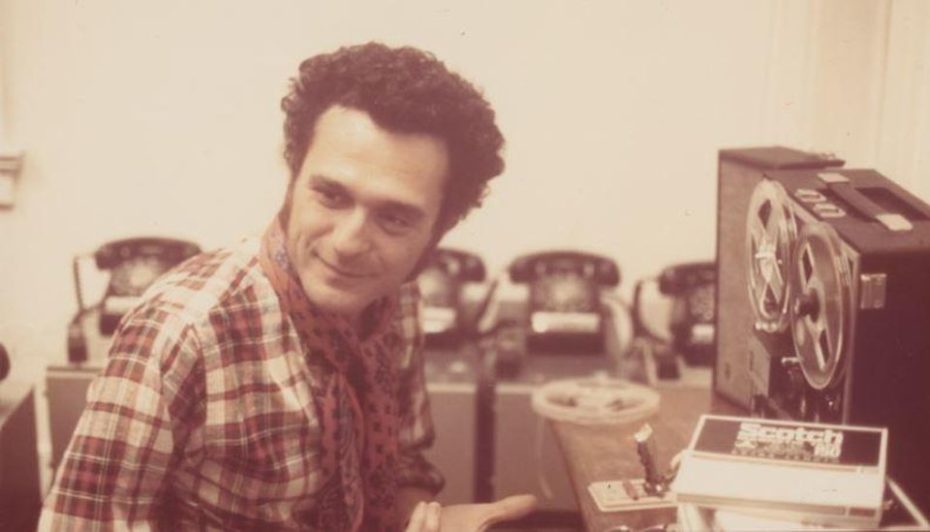

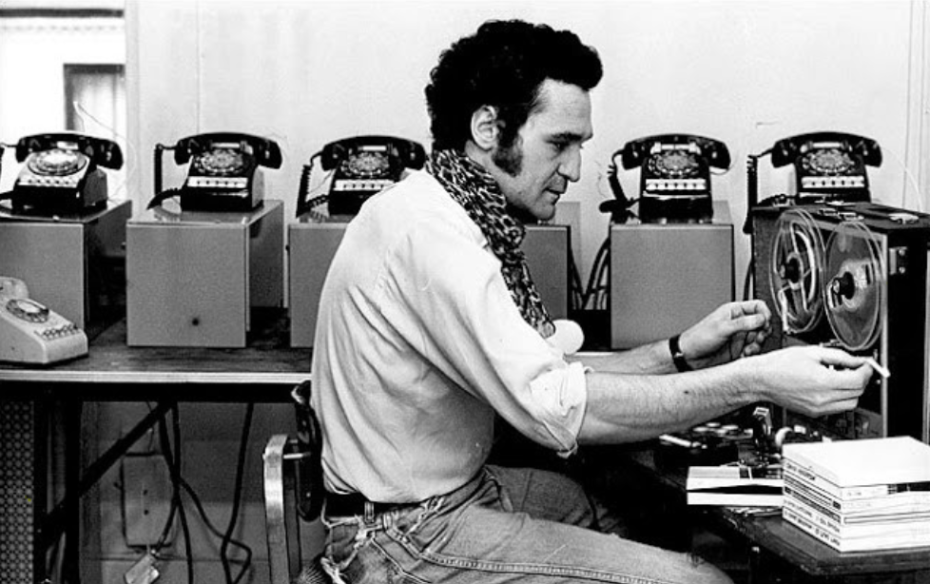

And so, Dial-A-Poem was born. Fifteen rotary telephones were set up in a room at the Architectural League on the Upper East Side, and rigged up to a bank of bulky recording devices. Wires were everywhere, and the set-up would look entirely primitive to us today, but once upon a time, this was white hot technology. There were 15 answering machines for each of the phones, which you could call from anywhere and listen to a poem at random. Sometimes it could be sound art or political speeches, comedy or music. The hotlines were changed every day by Giorno with new selections. Stickers advertising the phone number were placed in public phone booths, in cafés, on bulletin boards and on the subways.

“We started and we got a few phonecalls in December, but then on the 13th of January […] we got a quarter page or a third page in The New York Times […] and they talked about it and praised it as an artwork […] but they put the telephone number like three times, and that set it off. Everybody in the morning … when you go to work […] and you’re bored and you see this, you pick it up and then it becomes a drug. If you’re bored with John Ashbery, you hang up and you’ll get Jim Carroll.”

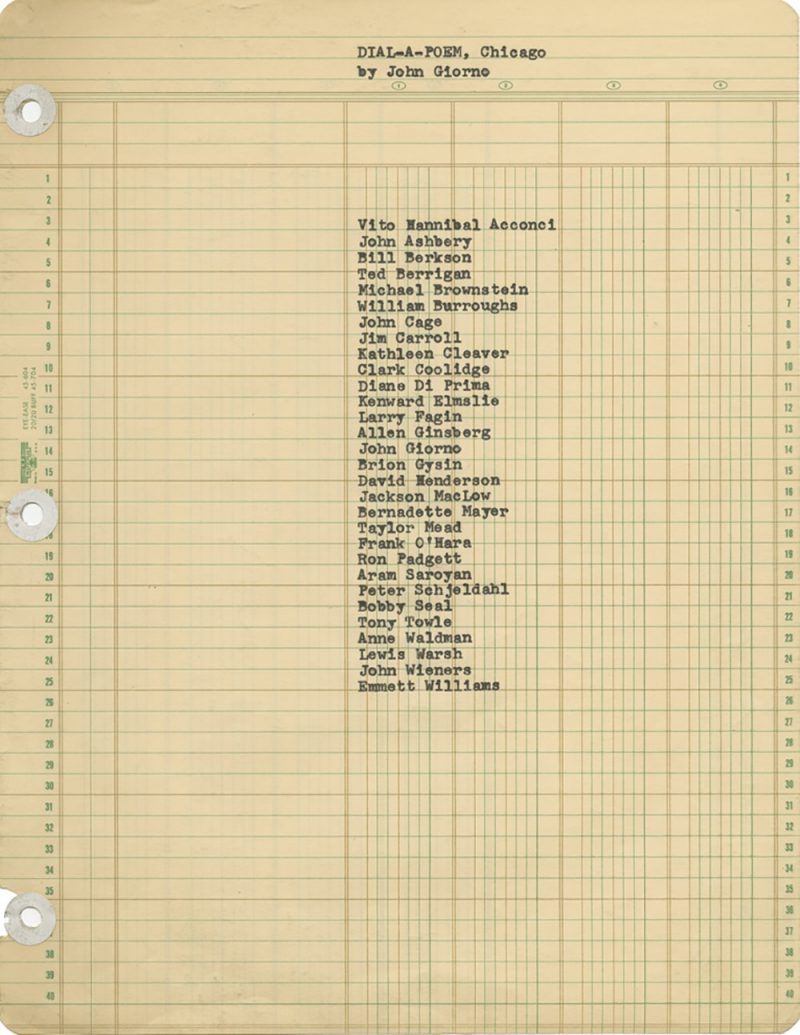

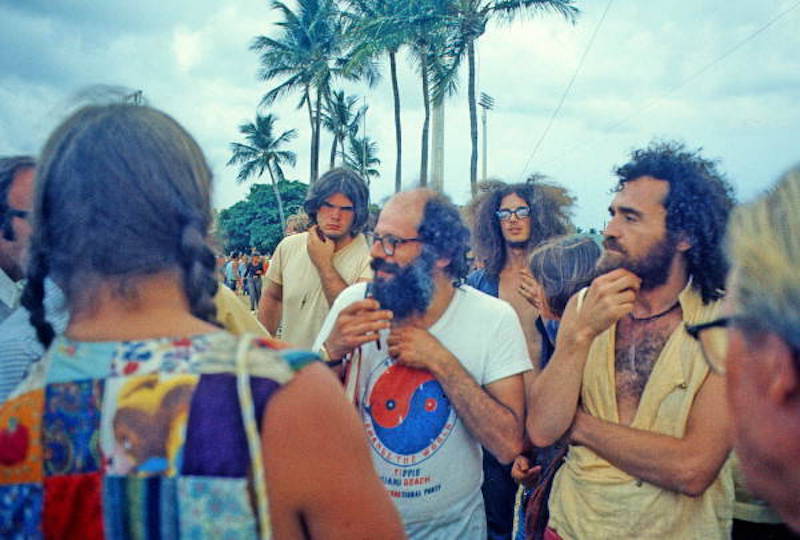

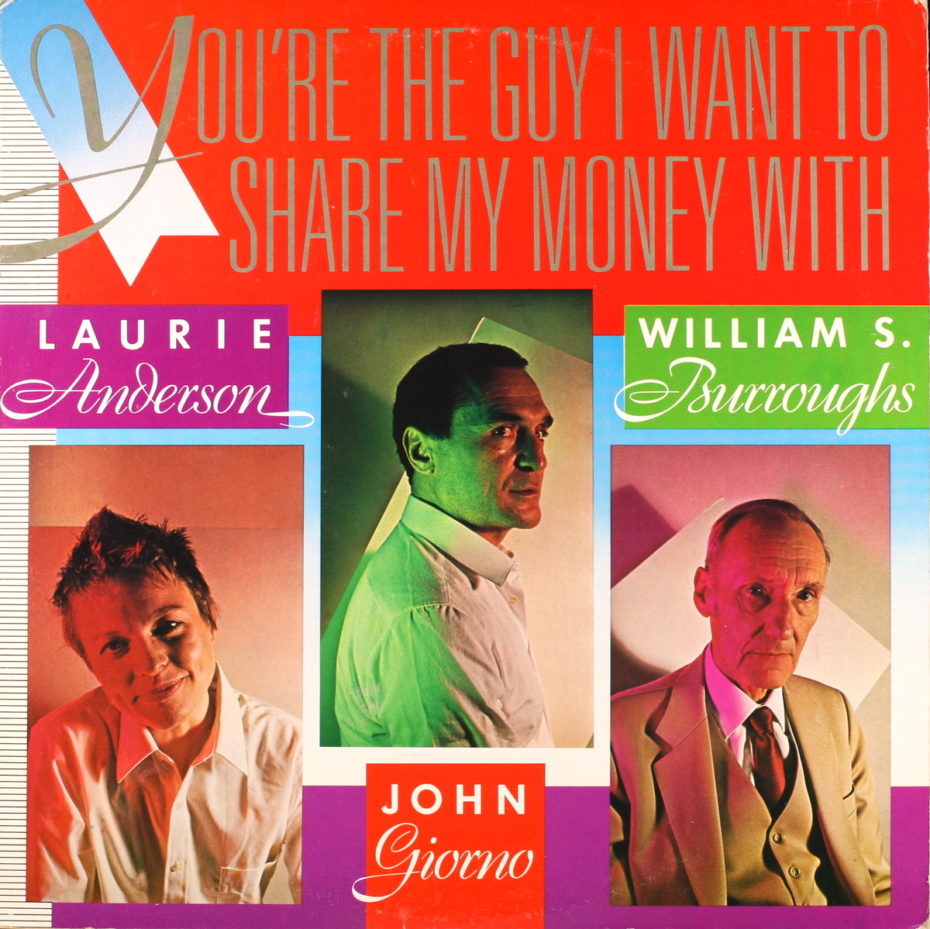

You could dial in and simmer down with John Cage’s quest to find a decent translation of a Japanese mushroom haiku, listen to an early piece of sound art by Phillip Glass or get revolutionary advice from beatnik poet Diane Di Prima. And how wild it must’ve been, to have the radical voices of the Black Panthers suddenly fill your bedroom, or the chanting of Allan Ginsberg himself. How delightful, to hear the eely voice of William Burroughs, another of the last figures of Ginsburg and Kerouac’s Beat generation, who read excerpts from Wild Boys.

Answering machine technology was not yet being widely used in the late 1960s, but within a few months of Dial-A-Poem’s launch, a tide of copycat dial-a-phone services soon had their own dedicated section in the back pages of The New York Times.

“The busiest time was 9 am. to 5 pm., so one figured that all those people sitting at desks in New York office buildings spend a lot of time on the telephone,” Giorno, told the New York Times in 2005. “The second busiest time was 8:30 pm. to 11:30 pm… the California calls and those tripping on acid or couldn’t sleep, 2 am to 6 am.”

As thousands of calls rolled in with each new press feature, phone companies threatened to shut Giorno down because the system was equipped to handle only so many calls and busy signals.

Much like the internet, suddenly, Dial-A-Poem had made something accessible that was not accessible to a lot of people, using technology. It was a network of random information, stories and poetry, and had the collective nature of a shared experience. Sounds more familiar now, doesn’t it? Giorno claimed the service later influenced the creation of all kinds of telephone information services, from banking to calling up your local cinema to listen to the showtimes. Remember that? But we might go as far as saying Dial-A-Poem influenced the internet itself.

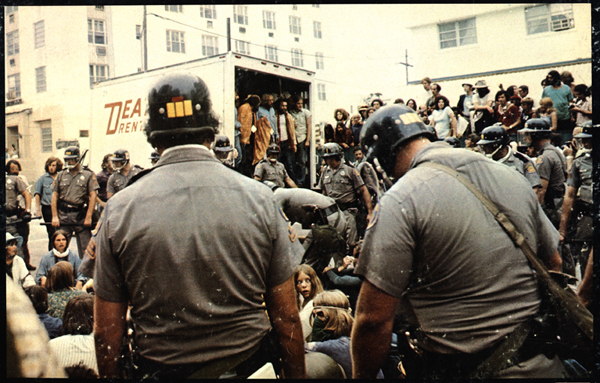

Giorno’s service attracted young and restless Americans, thirsty for their three recorded minutes of counterculture. And suddenly, its message had a place in a world of increasingly wide-reaching technology, media, and mass circulation. And once again, foreshadowing the internet, it could be full of great minds and radical thinkers, but also, some very intense and crazed people. That was the crucial thing about Dial-a-Poem: it reminded us that Flower Power was also agitation. That poets can be sentimental, but not all poets are sentimentalists. They can be fighters.

Giorno had invited hundreds of artists to record their voices and address numerous social issues such as the Vietnam War and the sexual revolution. You could happen upon the quiet poetry of John Ashbery and the cool pop of Debbie Harry, but you could also listen to the rapture of some of America’s most radical movements and even stumble upon a spoken recipe for a Molotov Cocktail.

When parents complained about inappropriate content their children were listening to, the FCC briefly shut Dial-A-Poem down and cut the lines. Giorno’s experimental art project had now become a threat to society.

The year 1969 is often declared as the nail in the coffin of the Peace & Love era. There was the Tate-LaBianca murders, and the killing at Altamont. There was the ease with which hippiedom had already reached the mainstream. Today, the concept of Dial-a-Poem might sound charmingly antique, but 50 years ago, it was radical, even dangerous, and certainly changing the face of poetry for generations to come.

That’s largely thanks to John Giorno. In a 2012 interview with Strombo, for example, Giorno stresses how comparatively little we recall about frequent Dial-A-Poem guest, Allen Ginsberg, in regards to his finesse with social justice issues – saying “he might’ve been a greater politician than a poet, even.”

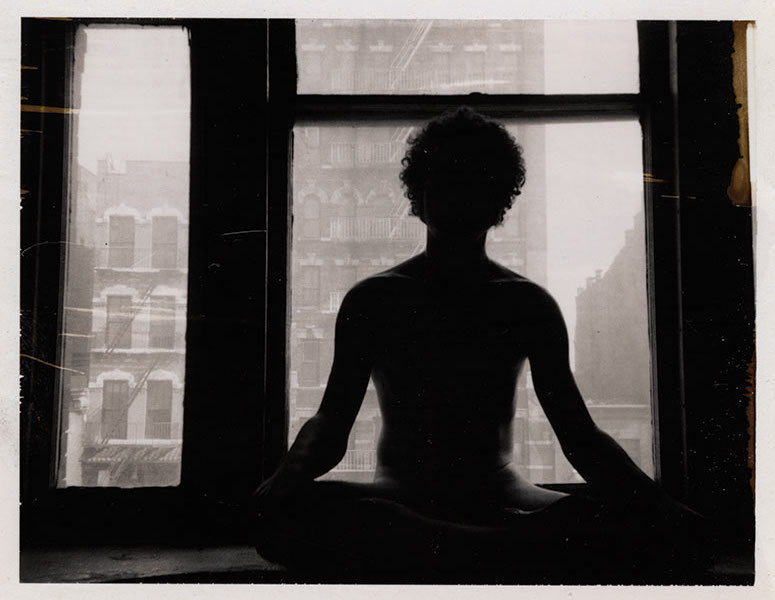

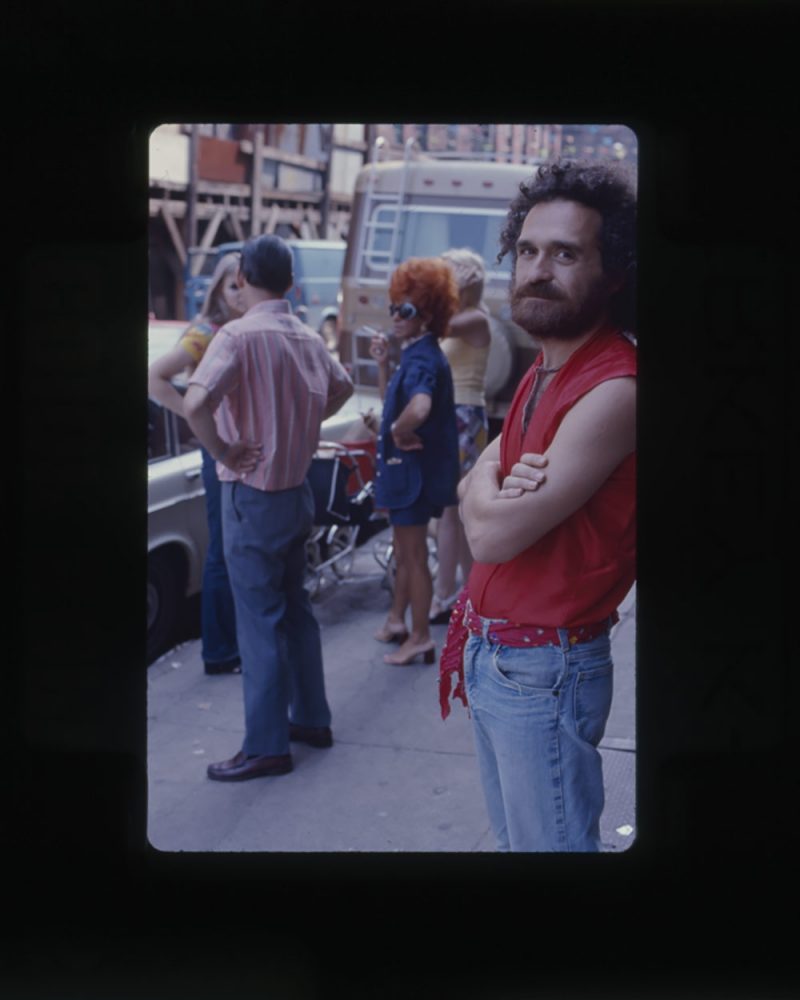

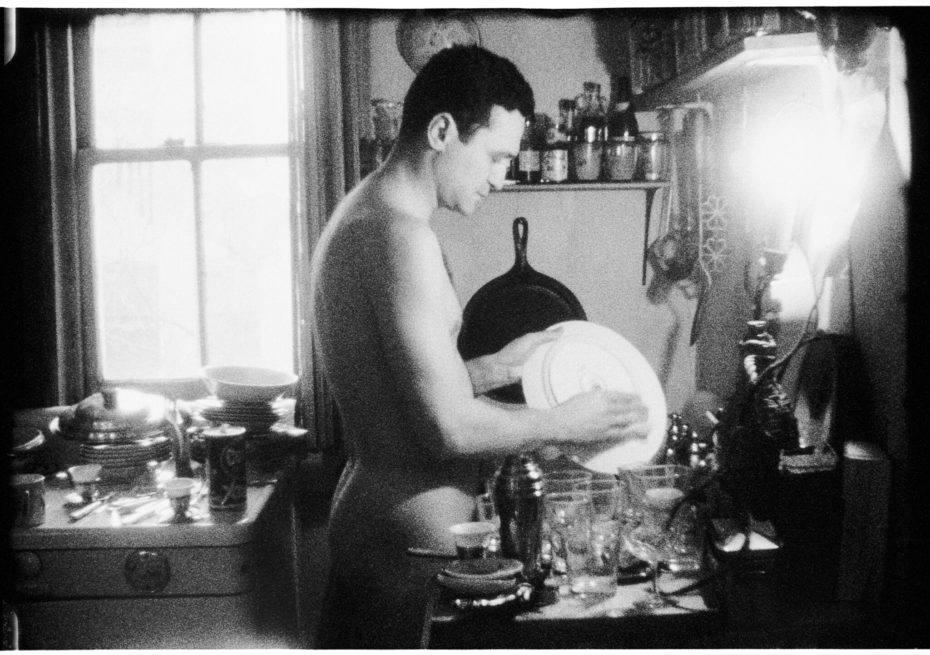

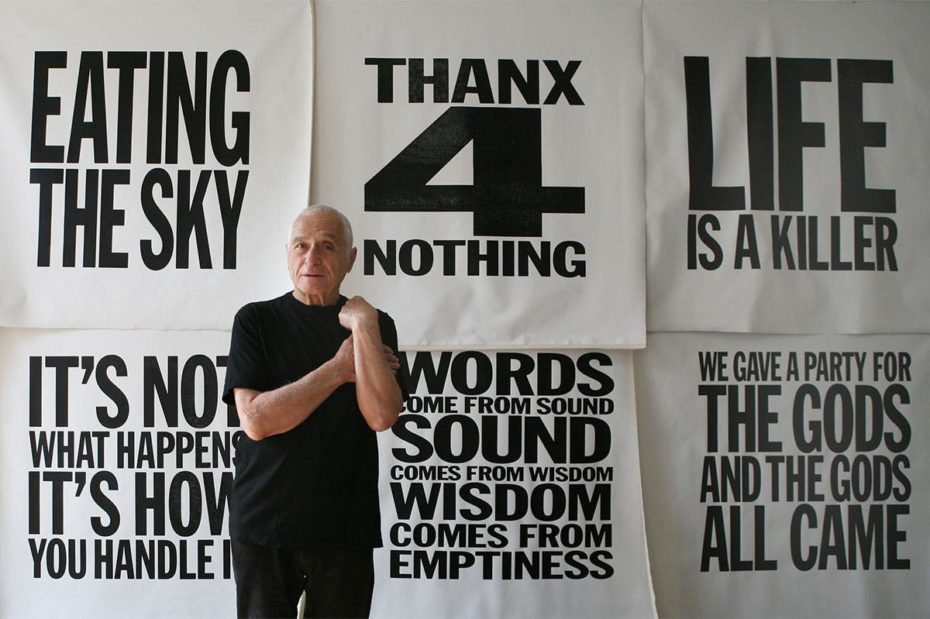

Giorno was a hell of a man. He had “Greco-Roman good looks and a gregarious, benevolent spirit,” as the New York Times wrote in his 2019 obituary. He was a Brooklynite, Buddhist, and stockbroker turned proud pornographic poet. He was very vocal about his experiences as a gay man – and an artist – and founded the AIDS Treatment Project in 1984.

In the 1960s, a chance meeting with Andy Warhol at a party changed his life forever. The two became lovers, and Giorno became the artist’s muse in films like Sleep (1964), in which the camera lingers over a dozing Giorno for over five hours. It must’ve been quite the romance.

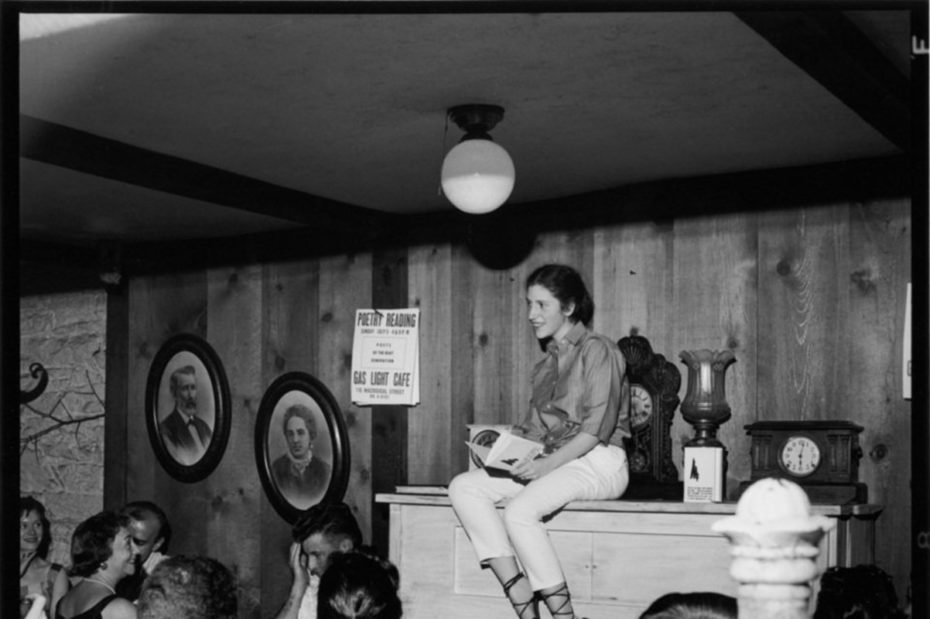

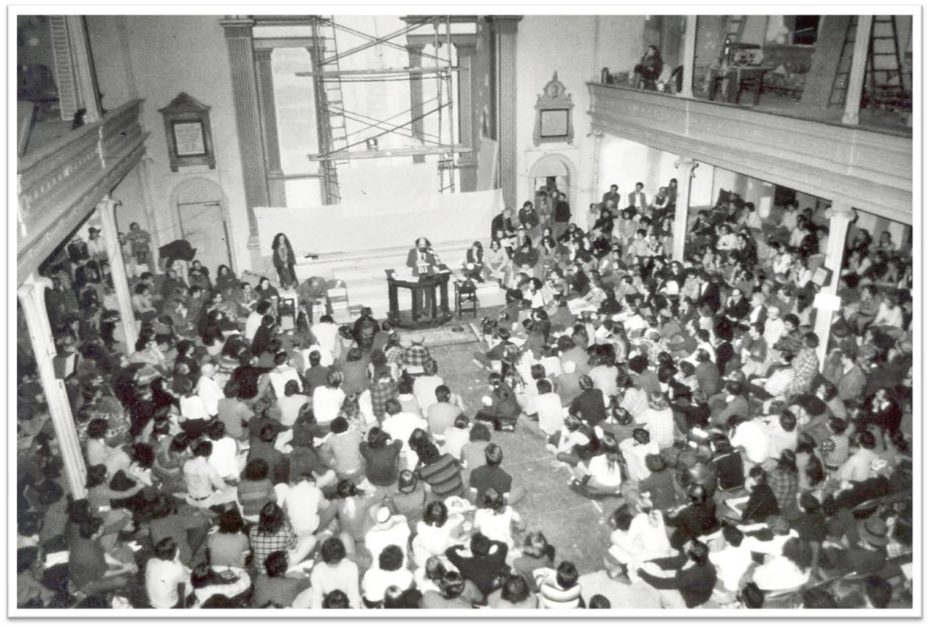

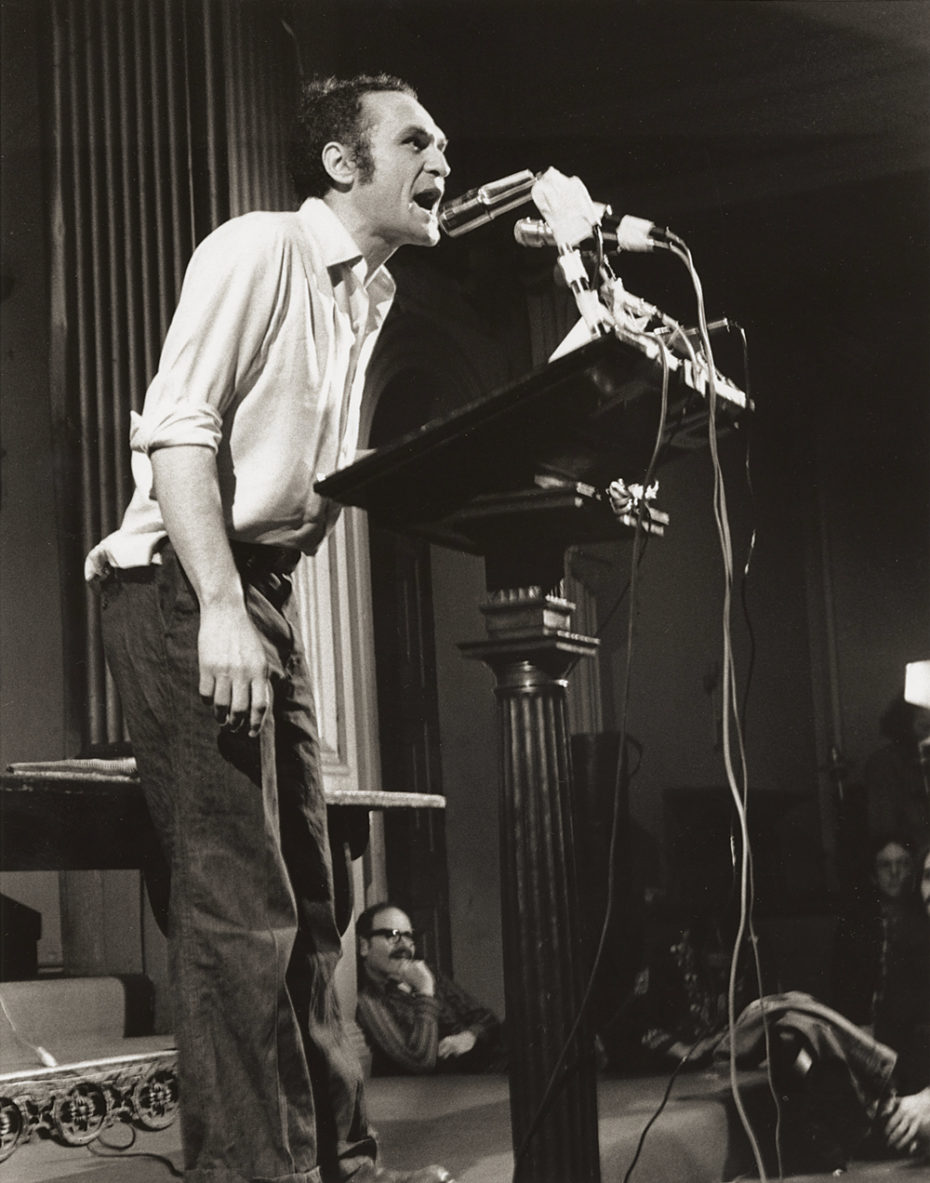

Giorno thrived in the art scene in New York, often using montage and cut-up techniques to create his own found poetry. After all, if Robert Rauschenberg could fracture the material logic of painting, why couldn’t he do the same with words? He started experimenting with sound distortion in his “Electronic Sensory Poetry Environments” in Manhattan’s East Village, where town hall-style forums basically became freewheeling open-mics on weed and justice, consciousness and sex – all in in St. Mark’s Church.

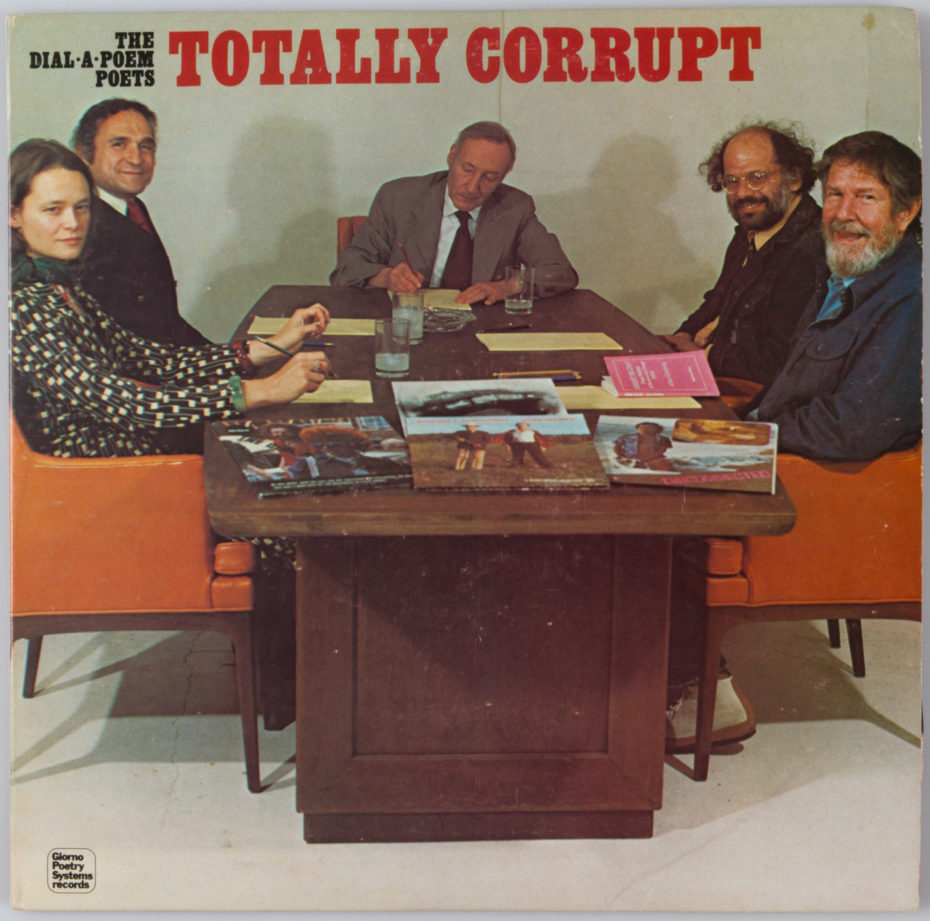

In 1966, “The Poetry Project” was established on its grounds, “premised on the vision that cultural action at the local level can inspire broader shifts in public consciousness,” in the words of its present website. Giorno also founded Giorno Poetry Systems (GPS), a cutting-edge record label that doubled as a non-profit and worked with Patti Smith, Robert Mapplethorpe, Philip Glass and others. There’s a whole vault of Giorno music collaborations to enjoy out there.

For the next few years, the Dial-a-Poem operation hopped around the city – but by 1971, it had ran its course. As imitation services offering everything from Dial-a-Jokes to Dial-a-Horoscopes filled the classifieds, Giorno’s Dial-A-Poem had perhaps lost its novely. Today, if you dial the original Dial-A-Poem number, (212) 628-0400, you get “Donna Messenger Clinical Care.”

In 2005, it moved online as a kind of open archive, and was briefly revived in hotline format in 2017 with a new cast of creatives – sponsored by Red Bull (ah, the irony). In short, it has seen some pretty formidable reincarnations. But it’s just not the same as 1969.

In the 1970s, Giorno perfected his confrontational performance poetry in New York City’s nightclubs and became highlight influential to the Poetry Slam scene. He spent much of the 1980s and 90s dedicating his time to AIDS activism. He founded an AIDS charity in ’84 and continued to keep his pulse on the New York art scene to raise awareness, working closely with artist Keith Haring. He died of a heart attack in October 2019 at the age of 82.

Photo: Peter Ross. Courtesy Almine Rech

We love the internet, unflinchingly, but we also long for the ritual of the rotary dial telephone – for the pulse trains of a landline ready to connect us to a singularly personal exchange. Especially during covid-19. That’s why we were so happy to learn of formidable Dial-a-Poem-esque projects like “Phone Call,” which similarly joined 22 artists and poets together in April, 2020, and of the UK’s National Poetry Library slating its own Dial-a-Poem service. In other words, poke around enough corners of the internet right now, and we bet you can find a hotline for you – and if not, why not start one yourself?

We’ll leave you with this timely Dial-a-Poem message by John Cage as an outro…

“More and more, I have the feeling that we are getting no where. Slowly, as the talk goes on, we are getting nowhere. And that is a pleasure. It is not irritating to be where one is. It is only irritating to think one would like to be somewhere else. Here we are, now. A little bit after the middle…orignally, we were nowhere. And now again, we are having the pleasure of being, slowly, nowhere.”

John Cage

And a wonderful look inside the world of John Giorno in this delightful interview at his and William S. Burroughs’ longtime New York City home: