“Inject disinfectant into the human body” sounds like the words of someone who flew over the cuckoo’s nest, doesn’t it? Well, once upon a time, women were encouraged to do exactly that, all to accentuate their “dainty femininity” and keep a rein on their man. And, if you were astute enough to read between the lines, it could also help a lady avoid having to rush down the aisle due to a pre-marital baby growing inside of her.

Yes, we are talking about “Lysol”; the world-famous household disinfectant, perfect for cleaning toilets, that was once used by women as a feminine hygiene product and contraceptive.

Historical facts really can be worse than fiction.

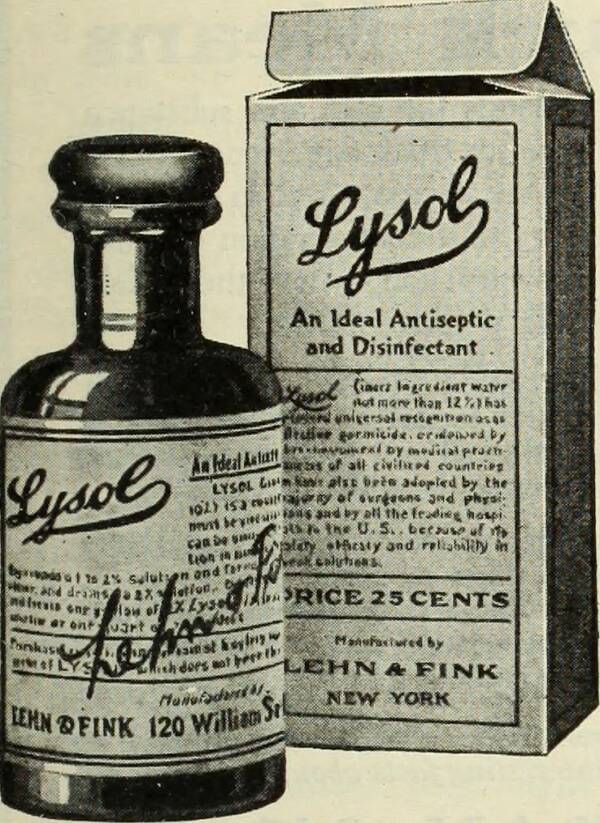

Lysol Brand Disinfectant was first invented in Germany in the late 19th century, originally used as a way to help with the cholera epidemic, after which it was also used to attempt to prevent the Spanish influenza pandemic in 1918. If it sounds familiar, they do say that history has a terrible habit of repeating itself…

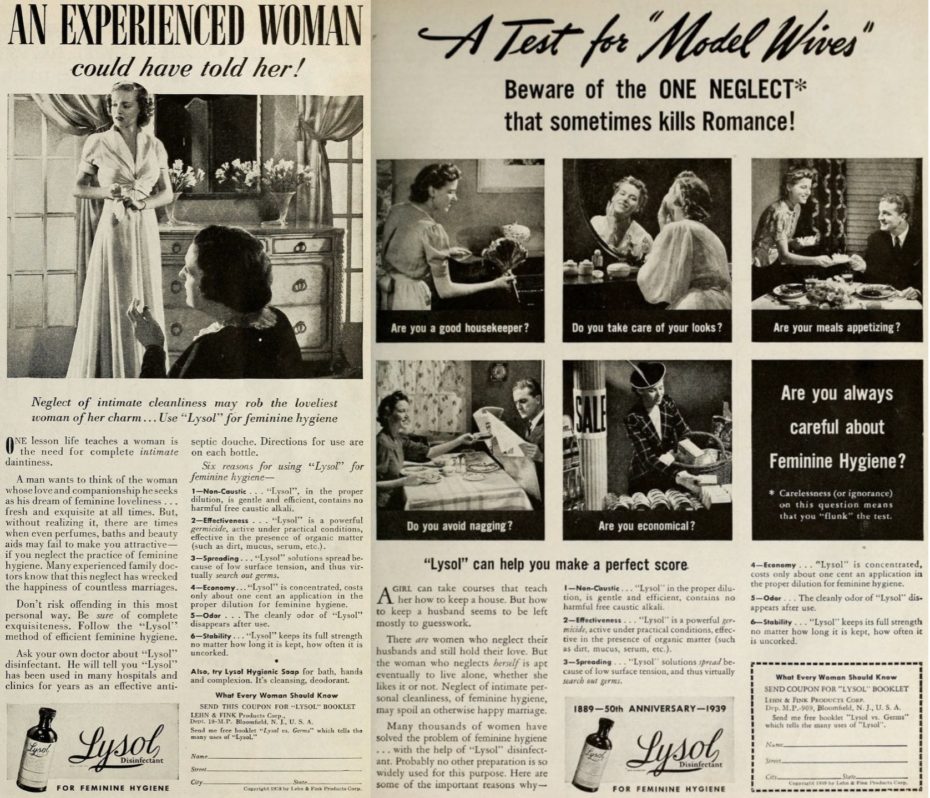

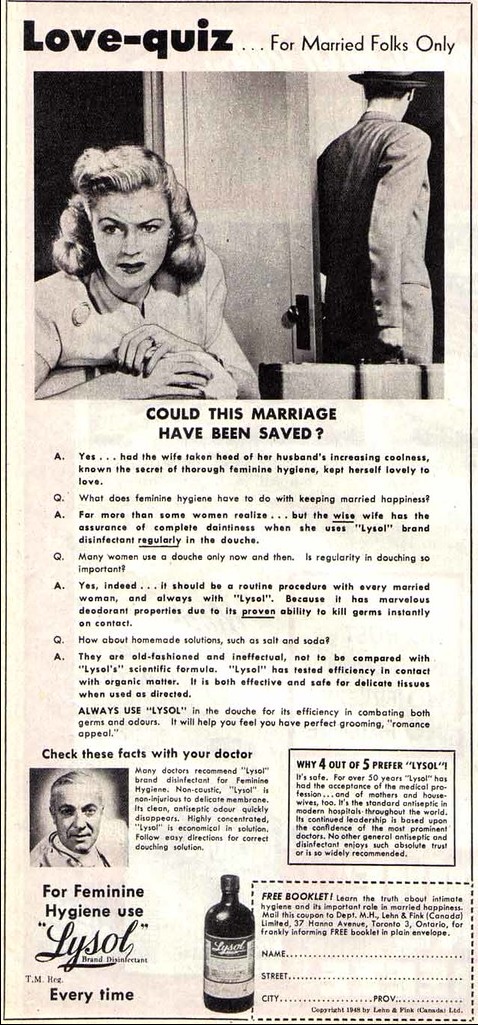

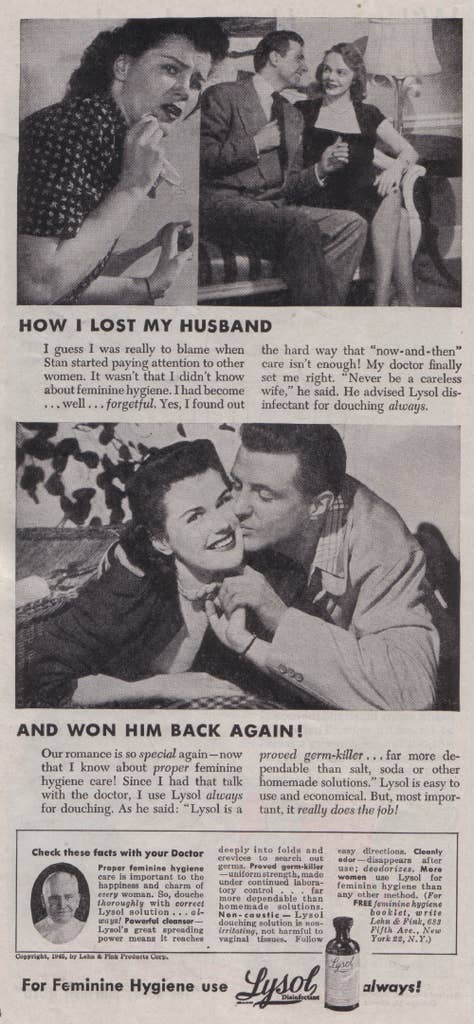

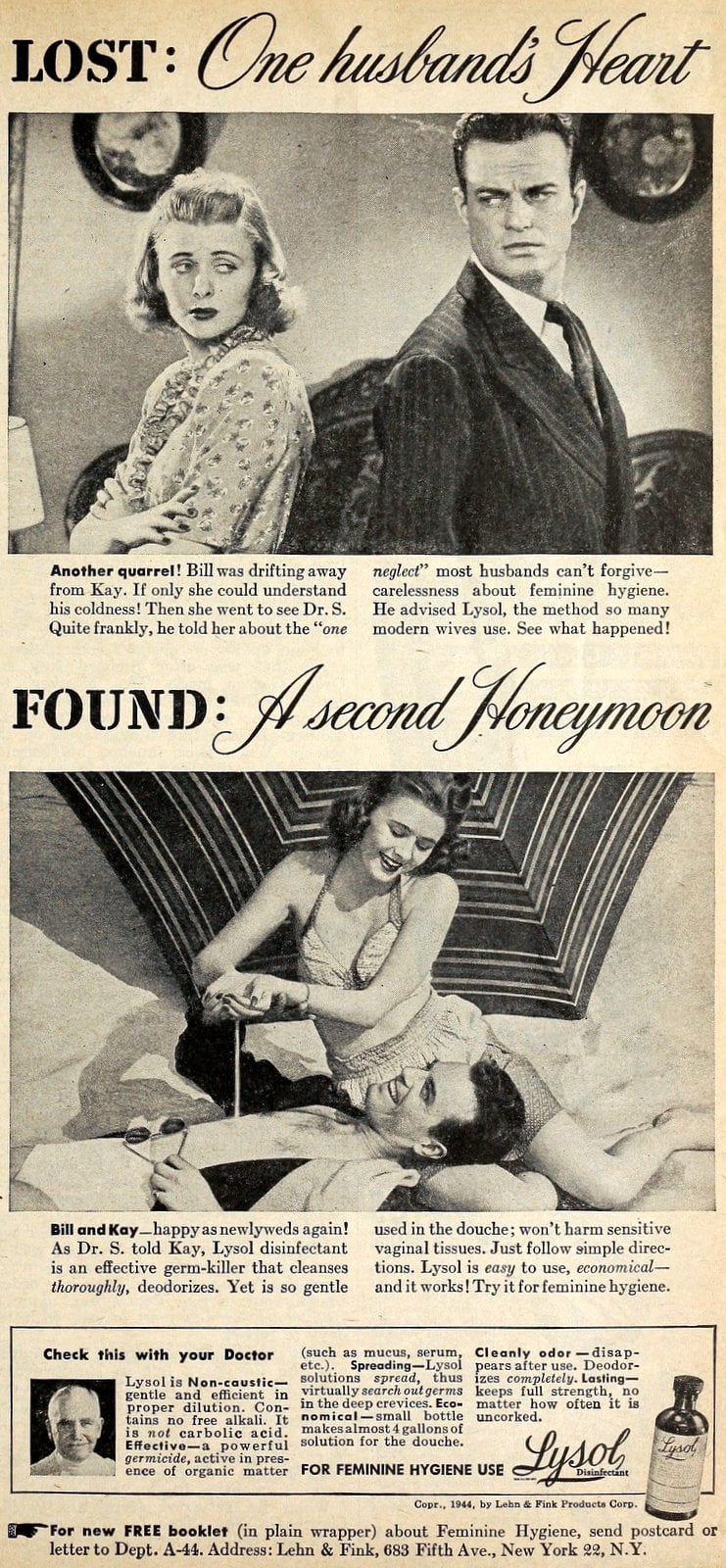

Soon enough, intrepid distribution companies, such as Lehn & Fink, had discovered a gap in the ever-growing consumer market. By appealing to a mass of anxious (read: oppressed) women, desperate to ensure the loyalty of their man, Lehn & Fink were onto a previously untapped resource. In one fell swoop, Lysol promised to reduce the chance of contracting unmentionable diseases while also maintaining what was referred to as a “feminine daintiness” as a way to “protect married happiness”.

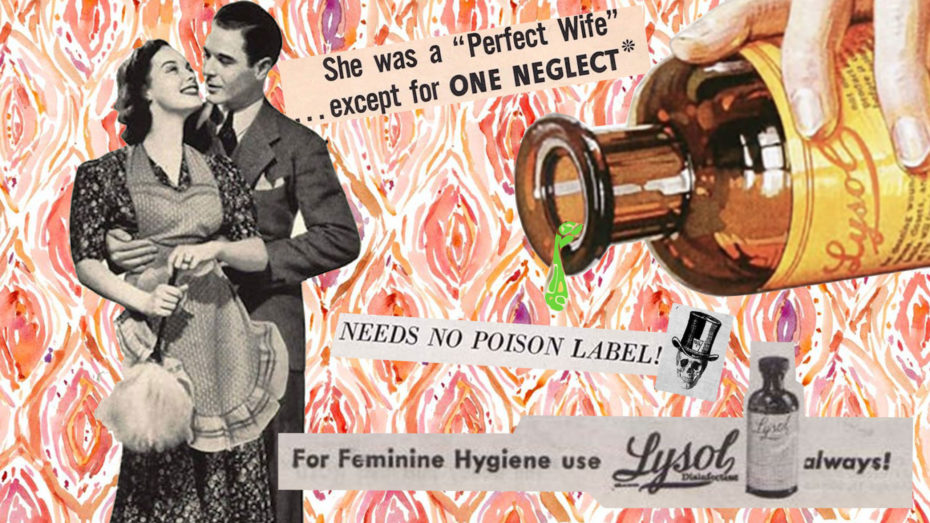

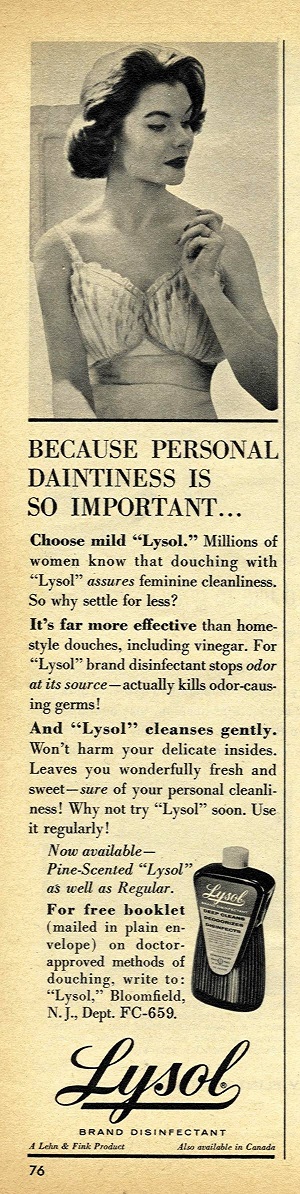

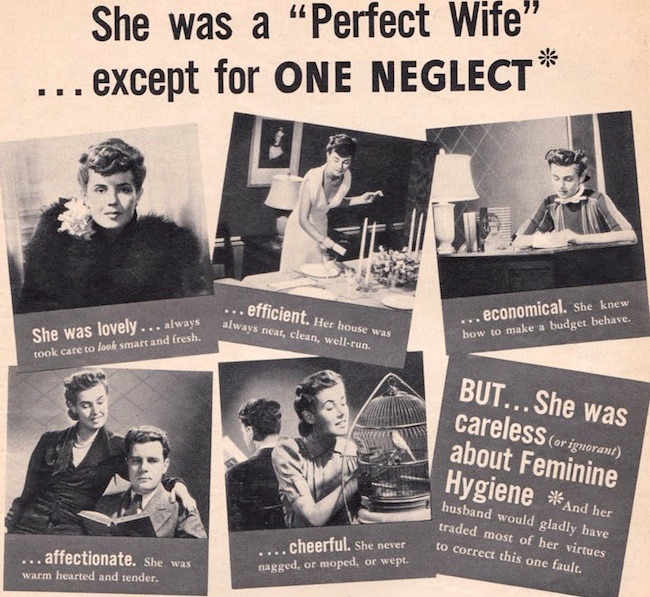

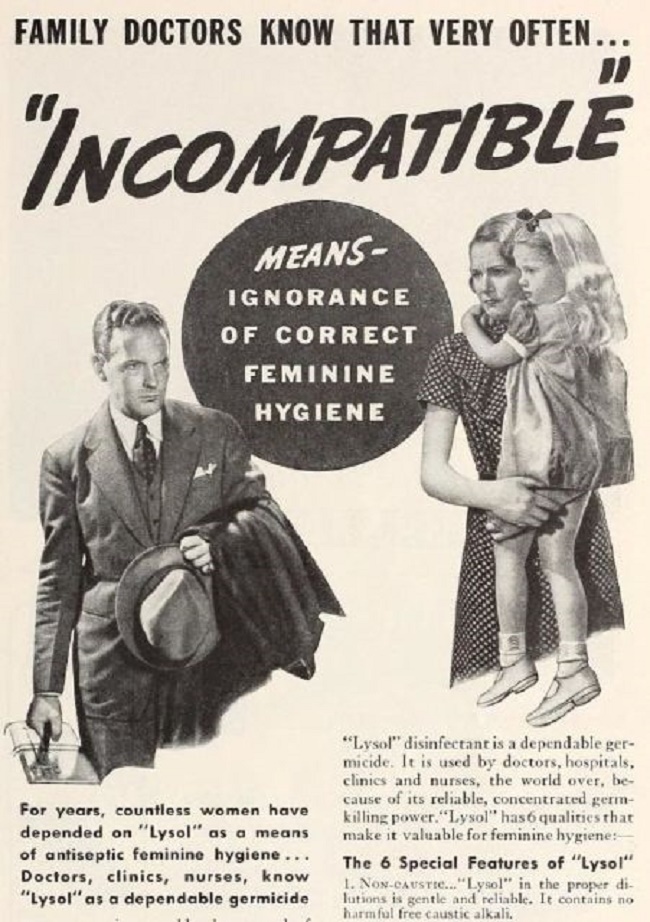

Of course, all of the problems women faced in those days were their “own fault” and something they could easily fix by douching with toxic fluids. Paired with intriguing advertising that grabbed attention as effectively as the romantic Hollywood film posters of the day, featuring glamorous women and dramatic tag lines, the product was lapped up.

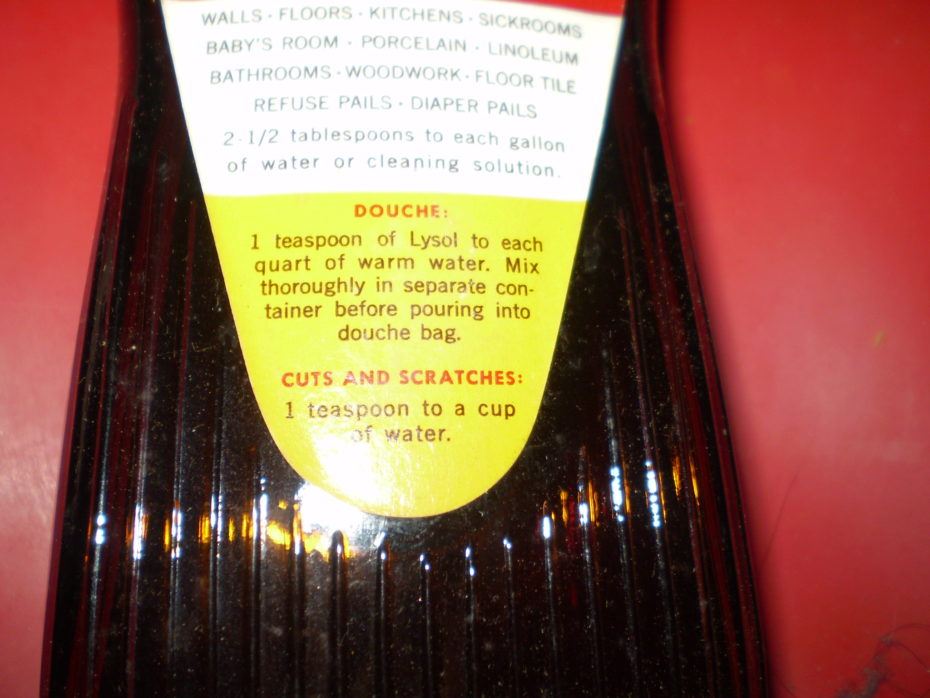

Unfortunately, by 1911 there were 193 Lysol reported poisonings and 5 deaths due to “uterine irrigation”. However, the disinfectant companies knew they were still backing a winner and the aggressive advertisement of Lysol as a “gentle and trustworthy” feminine aid continued.

Why with the threat of injury and death was the product still so vehemently loved by women? Well, first of all, the tragic tale of those affected were covered up, and secondly, perhaps even more important than “feminine daintiness”, the biggest reason thousands turned to such an extreme method of downstairs maintenance was contraception.

Due to the illegality of female contraceptives at the time, so many companies offering alternatives were seen as a godsend. On vintage Lysol ads, the words “feminine hygiene” was a very clever euphemism for “contraceptive”, with one ad claiming “Lysol passes the crucial test of a germicide, in that it is effective in the presence of organic matter”. “Germicide” was, yet another, very clever euphemism, and this time it rhymes with the word it was meant to replace.

From the turn of the 20th century all the way up to the 1950s, women claimed “I always use Lysol for douching”, because if the adverts were any kind of true-life reference, women were convinced that by not maintaining a caustic level of hygiene they risked losing their love interest to another.

And what would happen if women were ever to question the validity of the product? Any doubt would soon be eradicated with just one look at their ad campaigns, which would provide her with a warm and reassuring image of a “doctor”. Many of the Lysol adverts were published with an accompanying photograph of a mature, (sometimes handsome), smiling, male doctor, along with a testimonial of the effects, which inevitably made him and the product instantly trustworthy.

Historian Andrea Tone PhD records the investigation by the American Medical Association into these so-called doctors in her book “Devices & Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America”.

Surprise surprise, the doctors were fictitious.

By the mid-50s Lysol had changed its formula, however, by this point it had mostly stopped being advertised as a feminine hygiene product in the wake of hundreds of Lysol-exposed deaths, as well as multitudes of reports of injuries such as inflammation and chemical burns. Originally, many of these poor unfortunate women had been passed off as having “an allergy to Lysol”. Lehn & Fink covered up a lot of the complaints they received, and even still, by 1961 they responded to one well-publicised complaint, from a husband about the harmful effects Lysol had on his wife, by saying it was the “first complaint of its kind”.

The best part of the story is that Lysol was actually dramatically underwhelming when it came to preventing pregnancies. A study in 1933 of 507 women who used Lysol for contraceptive purposes shows that half of them ended up pregnant anyway.

Not to be dissuaded by a bit of bad press, the product was then promoted by doctors to mothers giving birth (no doubt to that pregnancy that occurred after using Lysol as a contraceptive). In 1938, American obstetric physician, Joseph Bolivar DeLee, began recommending the use of Lysol during labour as a way to “reduce the amount of infectious matter transferred into the uterus and wounds”.

Finally, in the progressive 1960s, a corner was well and truly turned for women in the western world. In 1965 in the U.S. and 1961 in the UK, birth control was legalised for married women, followed by 1972 and 1967, respectively, for single women. (It’s not hard to guess why 1967 was dubbed the Summer of Love!)

By 1968, Lysol was predominantly advertised as a home disinfectant only, with TV adverts recommending it as a great way to rid your home of germs.

And that, is hopefully how it shall remain.