Re-discovering history’s rebellious and obscure artists is one of our favourite pastimes on the internet. When their brushtrokes indulge their inner ghoul and become mischievous à la Edward Gorey, King of American macabre, or Oscar Wilde’s fearless illustrator who shook up Victorian society. Today, let’s unroll the black carpet for Mr. Harry Clarke and revisit his delightfully witchy illustrations and stained glass creations. As an Irish storyteller and artist, Clarke created a unique space for Pagan and Celtic symbolism to intertwine with that new thing called Art Nouveau, and the result was hypnotic: an oeuvre that brought new life to the world of both modern and ancient folklore.

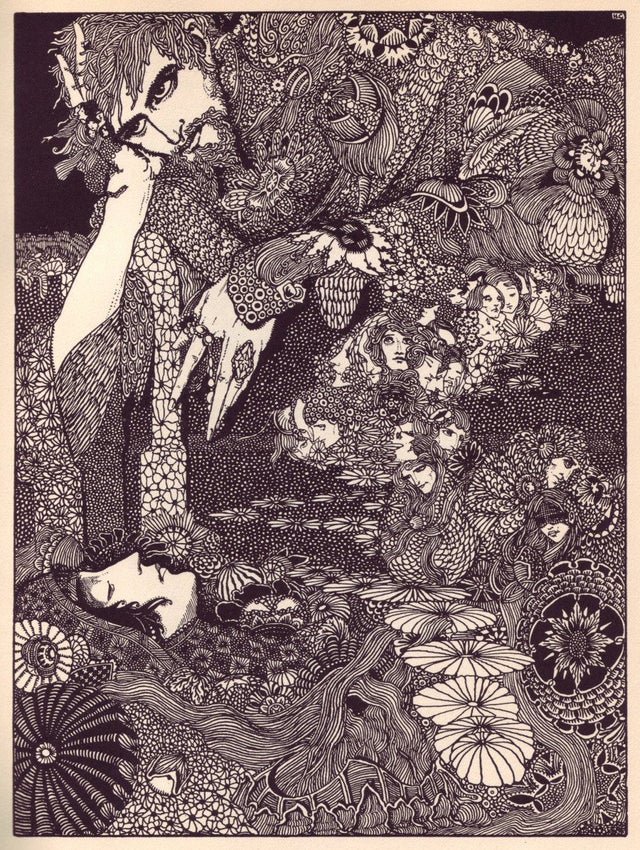

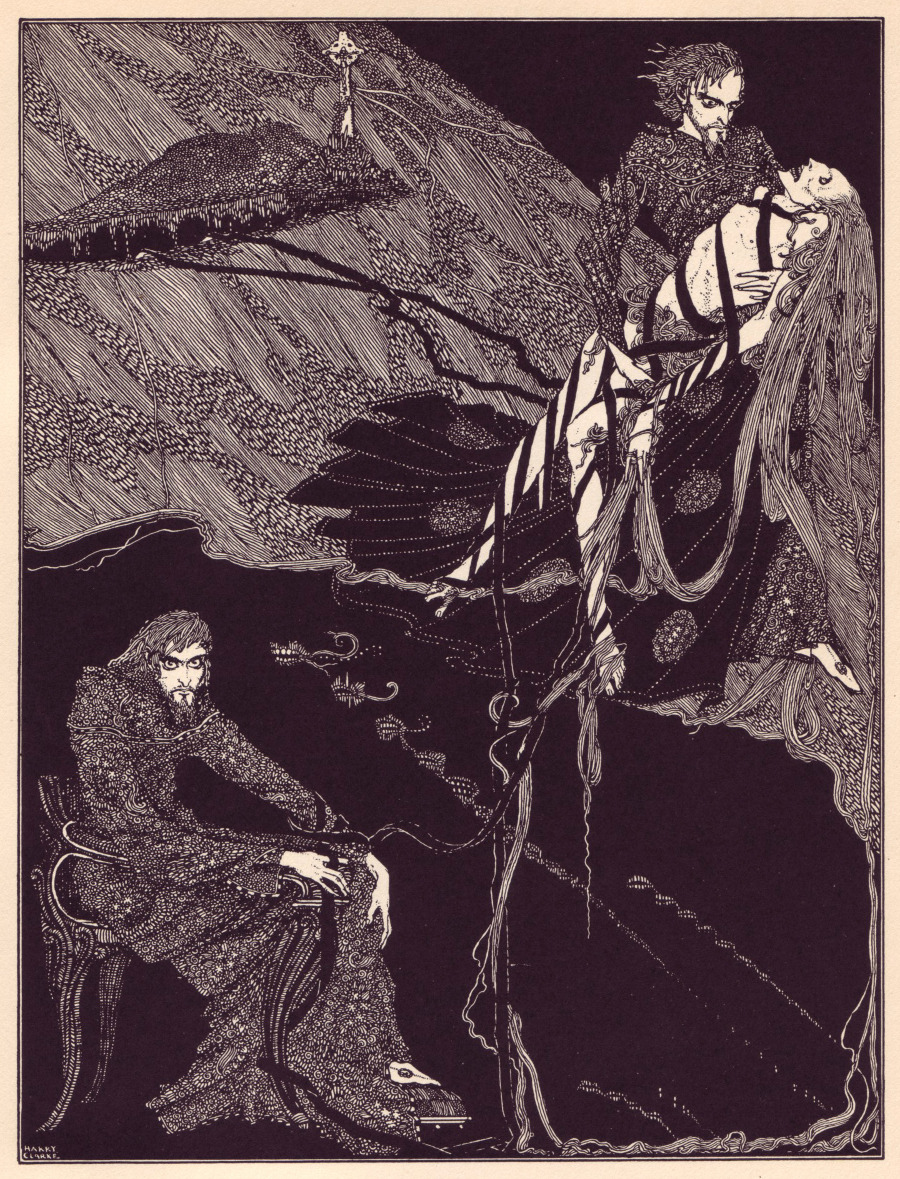

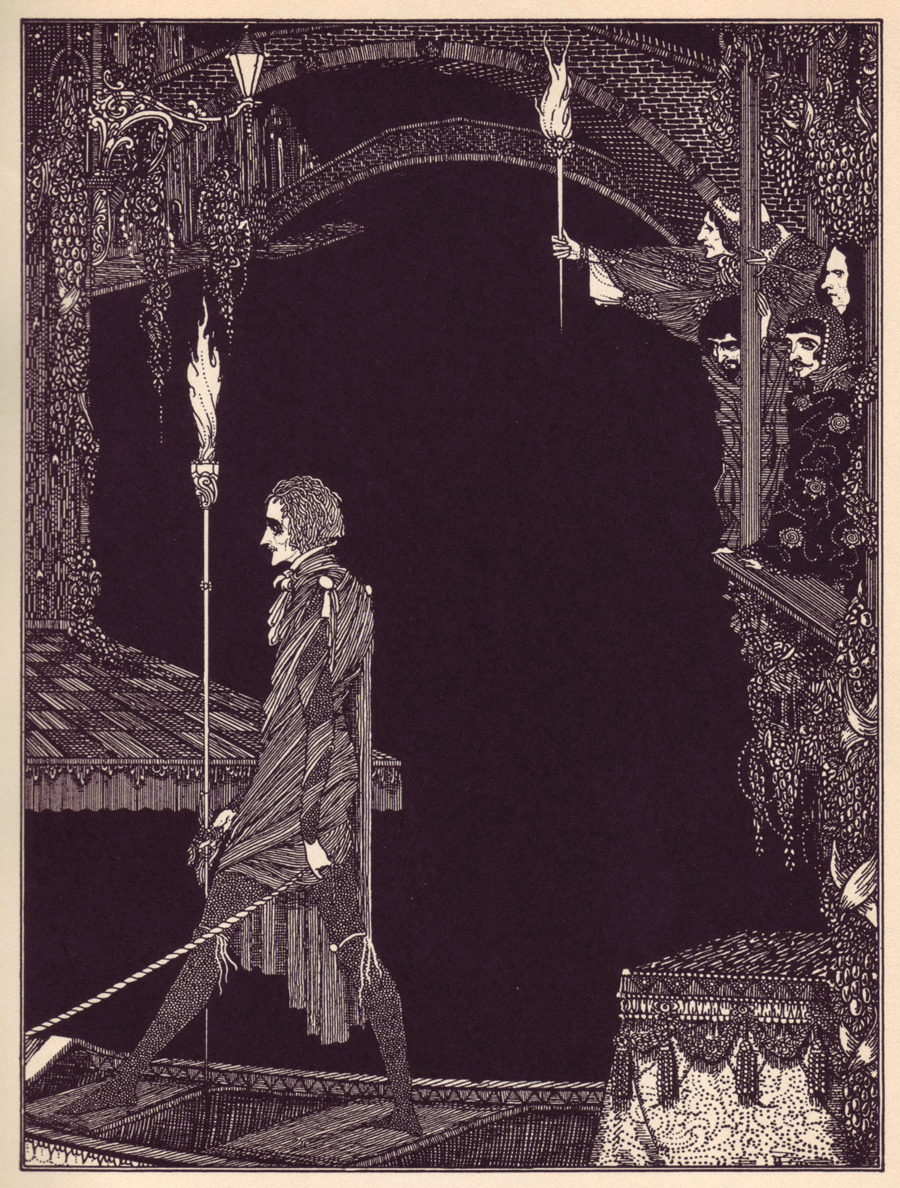

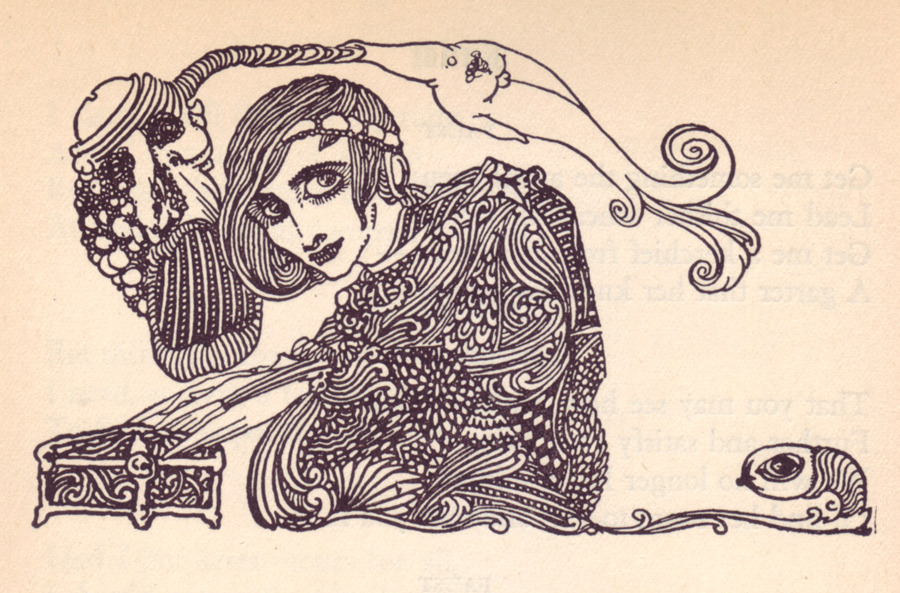

Clarke’s artwork was almost obsessive in detail, covered edge to edge with detailed illustrations of flowers and abstract curves, figures dipping in and out of the dark; we see vines crawl to life in one corner of a page, and torches flicker in another. The seemingly endless, minute twists and turns of Clarke’s pen brink on the psychedelic, almost half a century before the hippies. In fact, his work reminds us just how much Art Nouveau inspired the psychedelic designs of the 1960s.

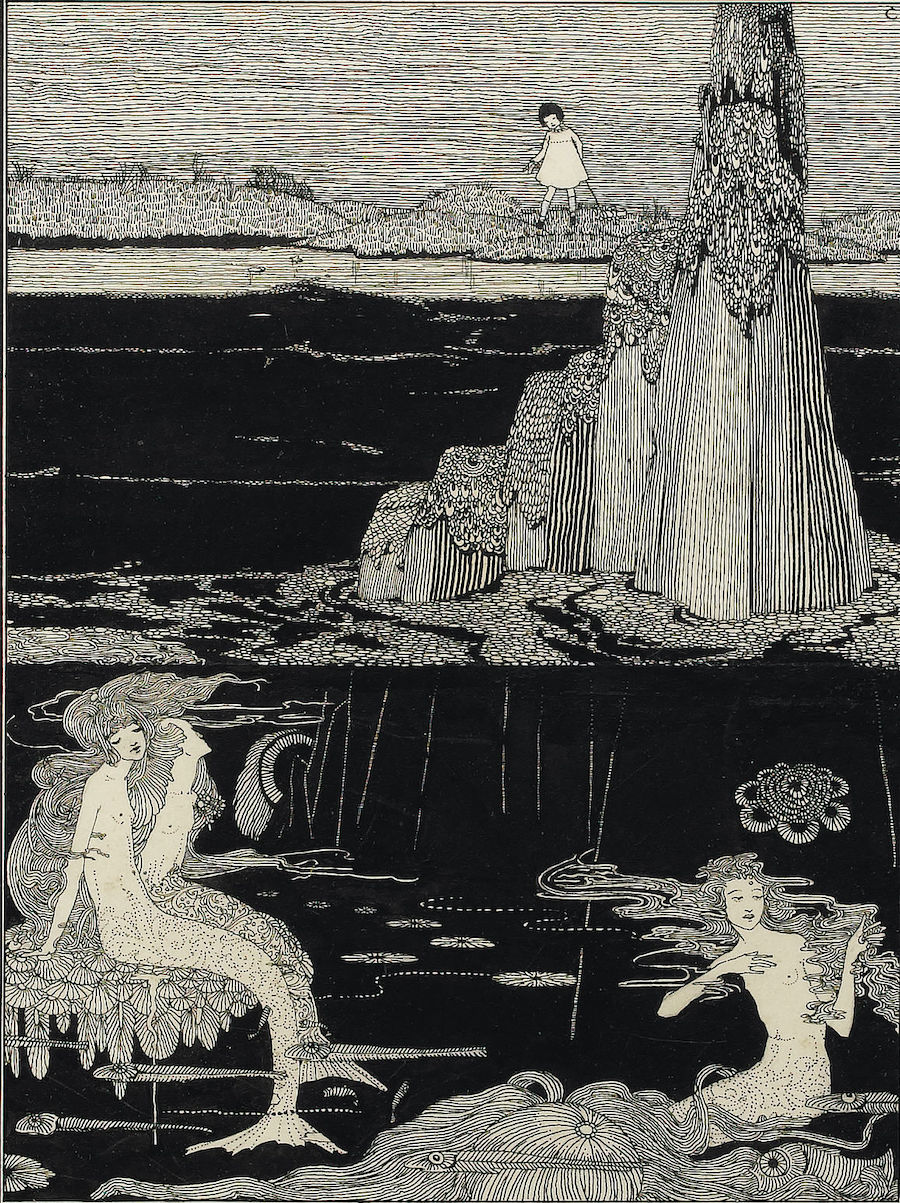

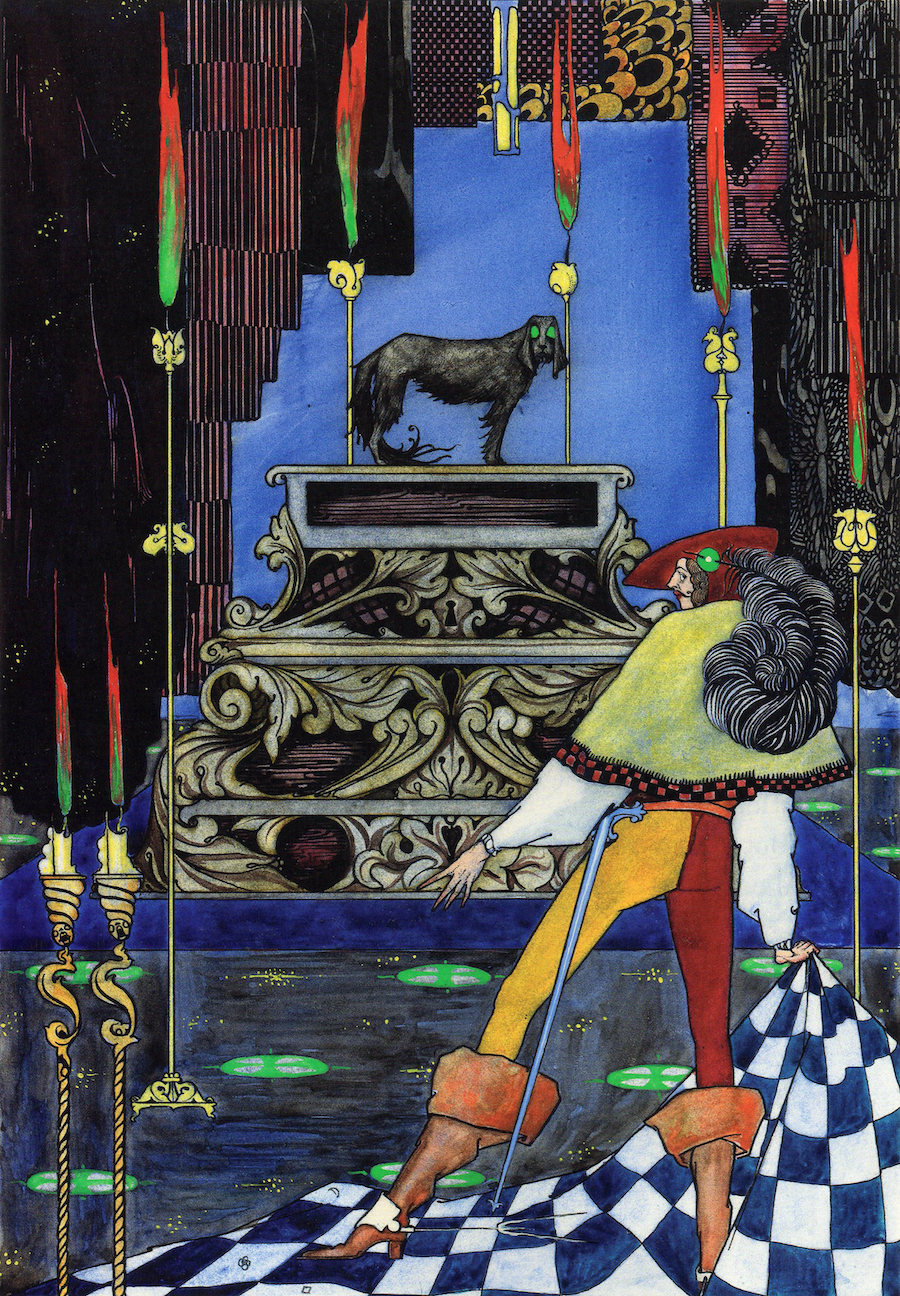

Turn up the acidity on the colour palette and Clarke’s dynamic designs make a perfect background for any free lovin’ rock concert poster. Even the hippie fashion is already there in Clarke’s 1916 illustrations for Hans Christen Anderson’s Fairy Tales.

Clarke was a natural storyteller. He was from Dublin, Ireland, after all, where a rebellious spirit and a streak of the poet is a birthright, and folks grow up with fireside tales of faerie-circles and Celtic lore. Only, Clarke let his brushes do the talking, studying art and stained glass (the family trade) with his father from an early age. Tragedy struck when his mother died at just 14-years-old, which may have influenced his instinct for darker tales…

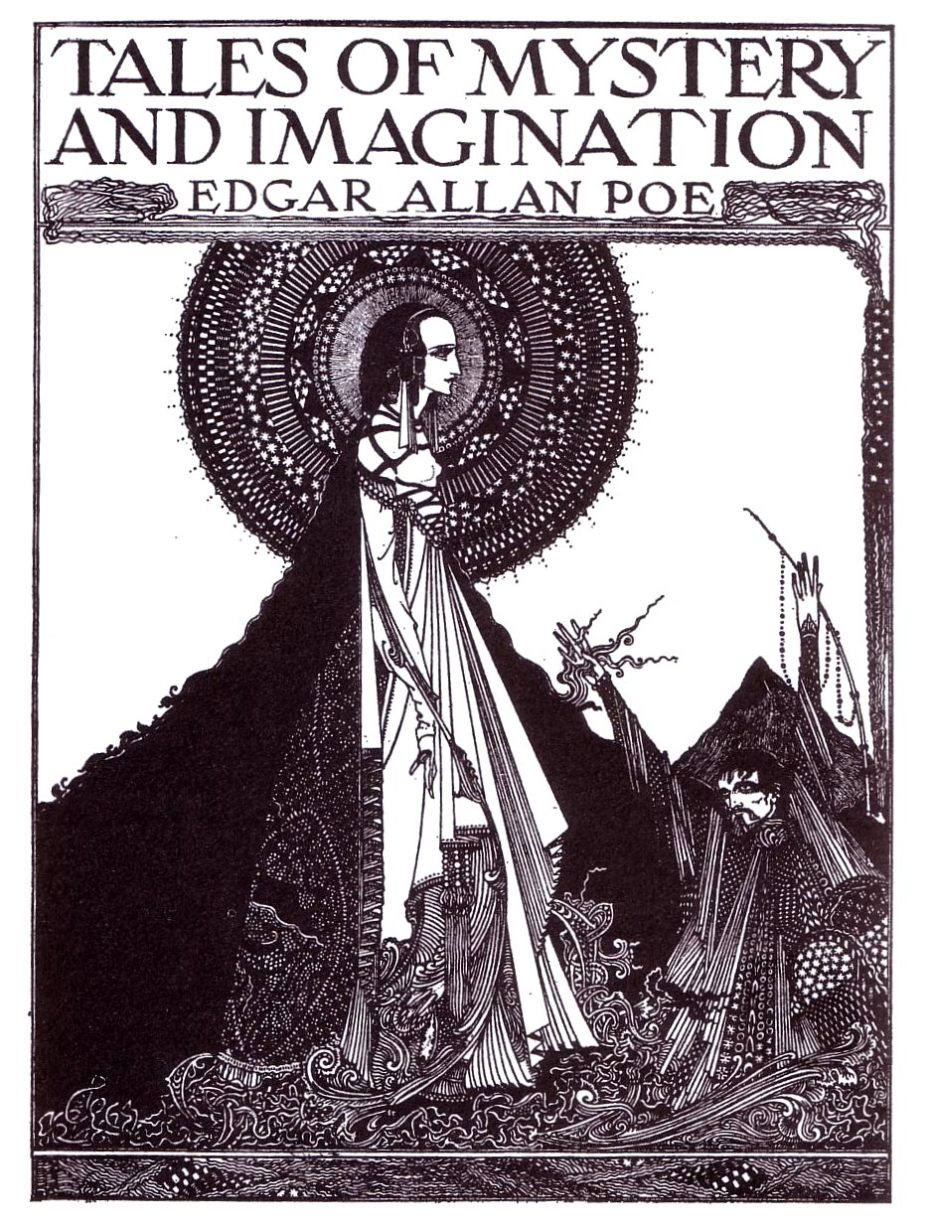

He moved to London to kick off his book illustration career on the heels of the Symbolist movement, for which esoteric affinities and “primordial ideals” were key values, paving the way for Art Nouveau’s fixation on the natural world to bloom.

Major global players of the Symbolist Movement included Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Baudelaire, and Paul Verlaine; Gustave Moreau, Claude Debussy, and Oscar Wilde – creatives whose writing embodied a sense of decadence and escapism. Clarke’s work would be no exception, joining the ranks of fellow fairytale illustrators like Aubrey Beardsley, Kay Nielsen, and Edmund Dulac. Like his contemporaries, not all of Clarke’s drawings lived on a strictly black and white spectrum…

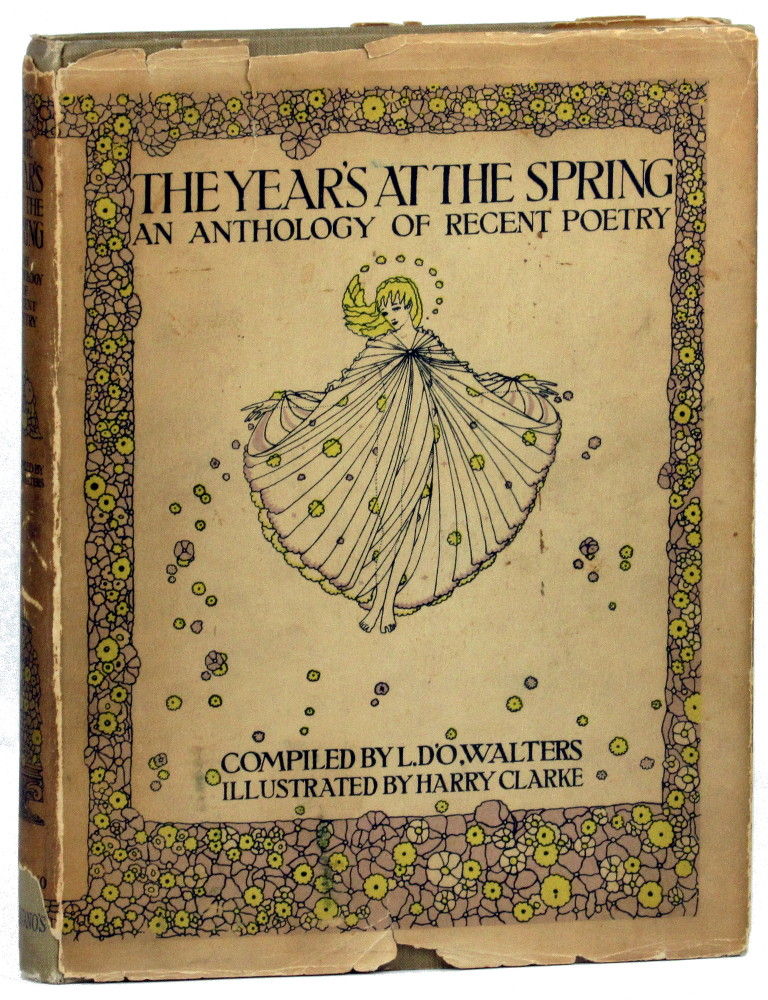

Part of why Clarke’s work did so well, was that it blossomed in tandem with the golden age of “gift book” art. Before photography became the public’s obsession, such elaborately illustrated books of poetry and fairytales were the ultimate must-have item for any chic library.

We like to think Clarke’s work for the poem “Hesperia” in Selected Poems of Algernon Charles Swinburne (1928) would have made a lovely housewarming gift, or his anthology of poetry tailored for Springtime…

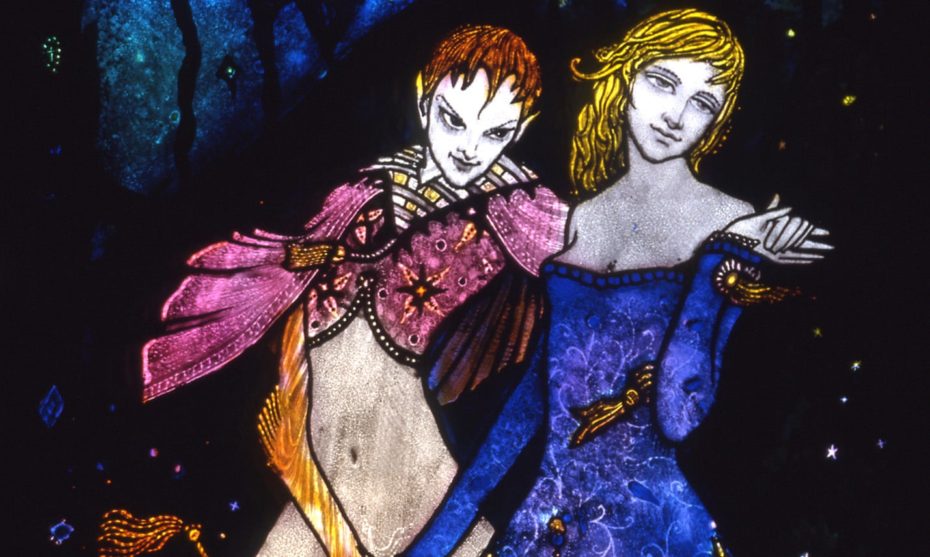

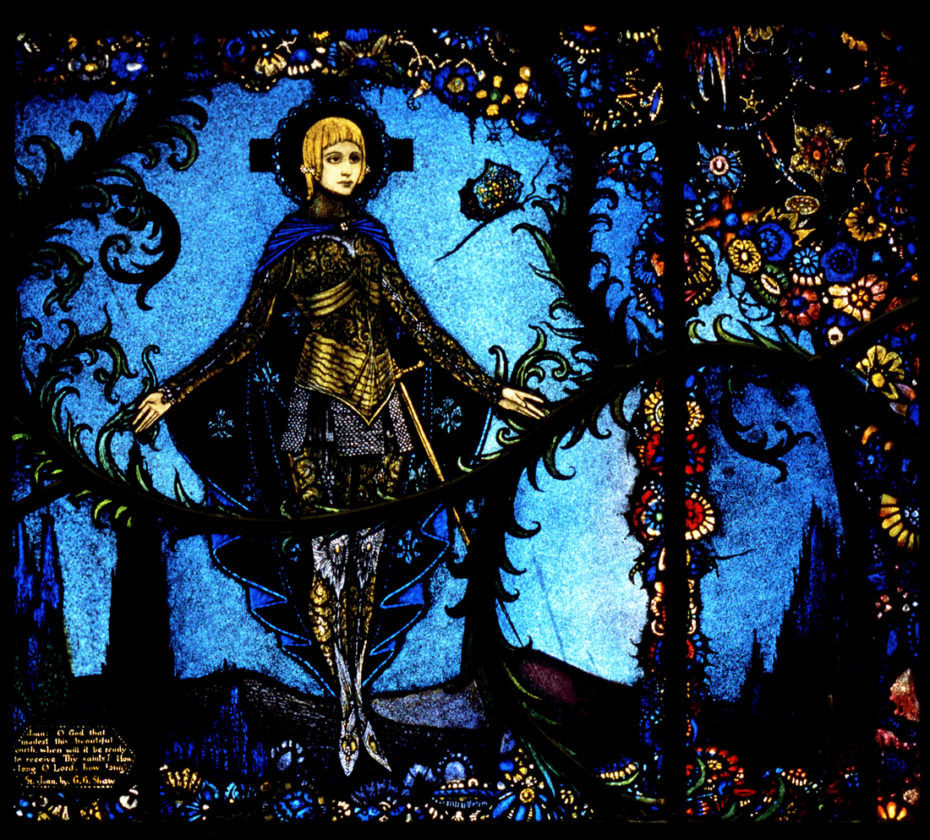

Where Clarke truly stands out from his contemporaries, however, is in his stained glass work, which made him a leading figure in the Irish Arts and Crafts Movement. “His inventiveness with the details he devised to control the light and to further his composition is marvellous,” explain Lucy Costigan and Michael Cullen in Strangest Genius: The Stained Glass of Harry Clarke. He found a way of creating dappled light within his windows, of using deft brushstrokes to create a “glittering” garment or sunlit maiden.

Unlike his Realist predecessors, Clarke aimed for almost cartoonish scenes with giddy, even sensual undertones that made the Catholic church’s jaw drop. Ireland’s then-President, William T. Cosgrave, even put a halt to a 1920s government commission for Clarke upon seeing the finished outcome; it was supposed to be a gift to Geneva for the League of Nations, but Cosgrave took one look and said, “It would give grave offence to our people.” Take a look at the details, which include sexy, sinewy elf-like figures, a drunk guy with an erotic dancer, and more…

At the same time, you had living legends like Yeats crowning him “Ireland’s greatest artist in stained glass” in light of his refreshing, brazen approach to story-telling. This was a time in which the Irish Free State was gearing up, and Clarke’s commitment to individuality speaks volumes to that spirit.

There’s so much more in the portfolio of Clarke’s work than we can include in one post; he created more than 160 stained-glass windows for various churches, cathedrals, galleries, and private collections. You can also find him at the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery in Dublin, the Wolfsonian Museum in Miami, and even take tea with his glassworks at “Bewley’s Oriental Café.” The Dublin icon, est. 1840, proudly displays the stained glass of their favourite Irishman…

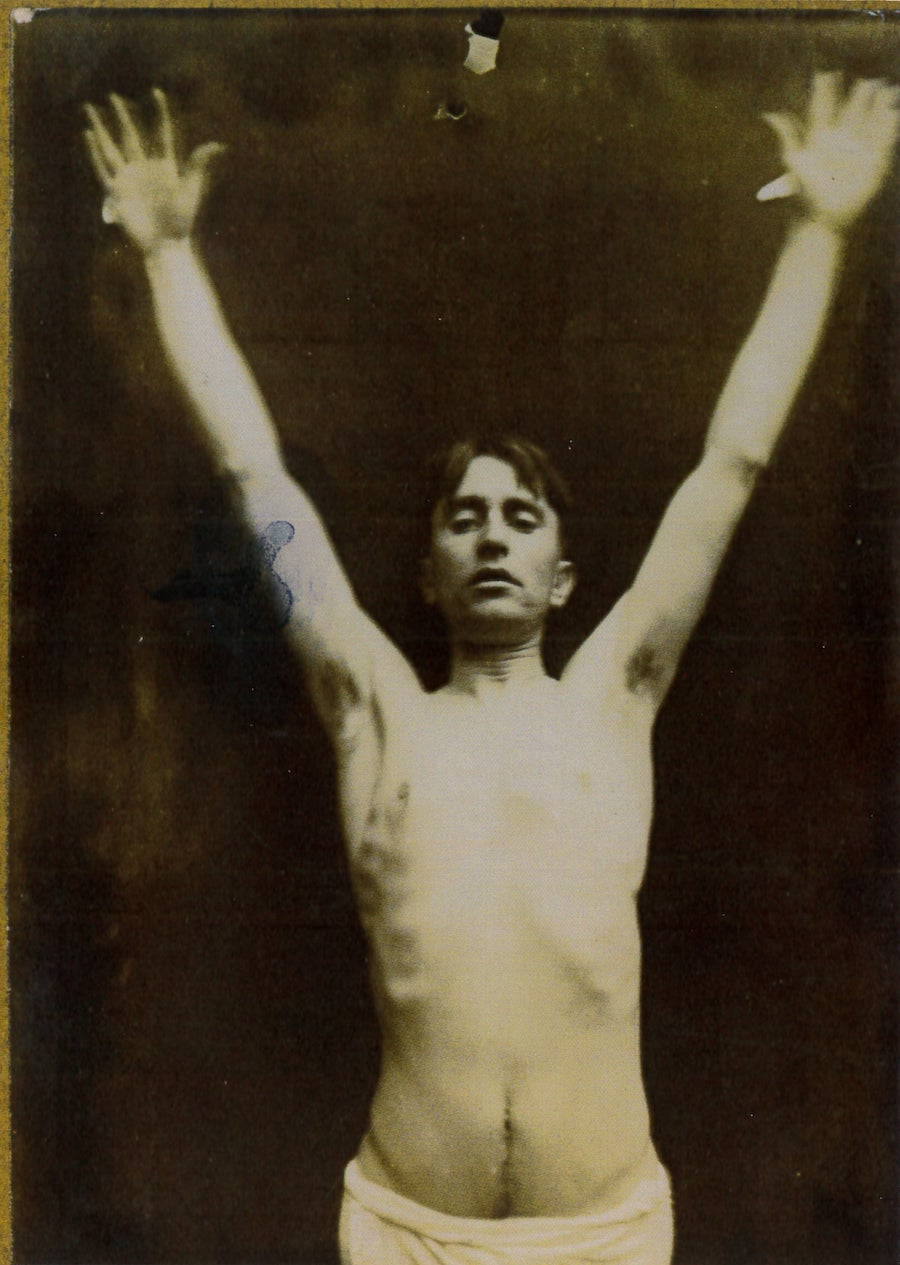

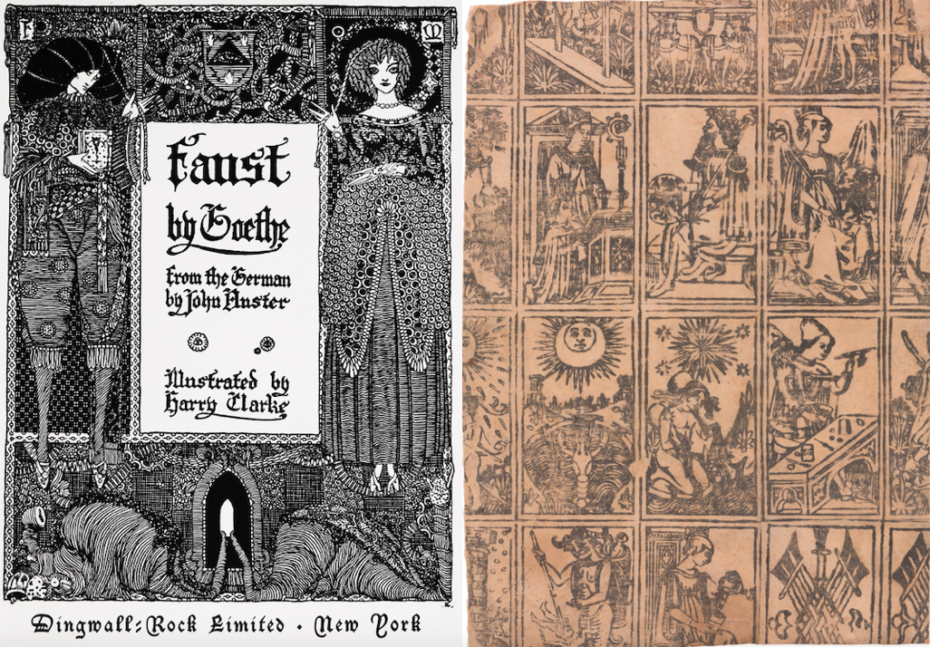

Clarke died young, in his forties, from a mix of tuberculosis and a lifetime of being around hazardous art materials. The last thing he ever illustrated was Goethe’s Faust – a tale of ego, temptation, and isolation. Once again, he tapped into ancient esoteric symbolism, this time from ye olde tarot cards. Some critics say Clarke bears a striking resemblance to some of the male figures.

If anything, may our takeaway of Clarke’s oeuvre serve as a rich example of the ways in which we make timeless tales – of horror, beauty, and bravery – our own.

It’s also worth noting the current value of Clarke’s work. There’s currently a copy of Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen, illustrated by Harry Clarke, going for $7,500 on the net. Another reminder not to judge dusty old books by their covers.