If there’s one thing we’ve learned over the years, it’s to listen to the muse – she usually has the juiciest details behind some of history’s most iconic artworks and artists. Today, we travel to the gauzy, sun-dappled world of the romantic pre-Raphaelite painters and zoom in on their unsung queen, “Ophelia” in that iconic painting. It turns out, she was incarnated by a real woman, Miss Elizabeth “Lizzie” Siddal, better known as the “supermodel” of the pre-Raphaelites, lesser known as an important and influential artist herself, and a poet too. Her story is just as heroic and haunting as that of the tragic Shakespearean icon she posed as for painter John Everett Millais in 1851 at the age of 23. It’s a story that gives us messy romance, obsession, and even a few ghost stories…

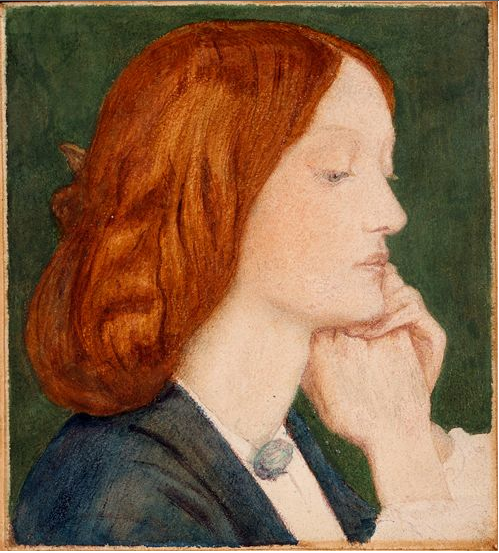

Siddal seemed fated to end up on the canvases of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a tenacious new art movement founded in the mid-19th century. In her, they saw the manifestation of all the stately, ethereal energies they craved. She was nearly 6ft tall, for one, and had a pile of radiant copper hair one could spot on the palest of English days. At the time, she was a stark departure from the well-bosomed beauties typically found in paintings – she had the pale Victorian complexion down, but her towering and gamine figure “changed the face of fashion,” writes Lucinda Hawksley in Lizzie Siddal: The Tragedy Of A Pre-Raphaelite Supermodel, “Her tall, boyish figure, with no breasts and no hips, was not at all the Victorian standard of beauty.” For the public, there was something intriguingly witchy about her coppery red hair and her disdain for wearing corsets, instead, opting to make her own free-flowing clothes. Often, it made her the object of ridicule in news press cartoons, and one journalist notes that in Victorian society, “the idea of red hair was thought of as social suicide”. Siddal’s confidence in her appearance and style was shaking up the game.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood only endured for a handful of years, but it totally turned the art world on its head. Founded by a troupe of irreverent, middle to upper class male artists, it eschewed what it saw as art’s yawn-worthy style, decline after the 15th century. Rather than simply focus on religious paintings spotlighting God’s son, they wanted to head out into God’s creation itself. To spend hours in nature, making it not just a backdrop – but a central character. And this was all long before the Impressionists. They wanted colour, tragedy, and romance. Most of all, they wanted a muse. In 1849, they found her in a London hat shop.

The Pre-Raphaelite Walter Deverell was supposedly strolling down an alley behind Leicester Square one day, when he spotted a 19 year-old Siddal at work in a hat shop. Deverell’s friend, William Holman Hunt, recorded precisely what he told his brotherhood that day: “You fellows can’t tell what a stupendously beautiful creature I have found. By Jove! She’s like a queen, magnificently tall, with a lovely figure, a stately neck, and a face of the most delicate and finished modelling: the flow of surface from the temples over the cheek is exactly like the carving of a Phidean goddess…” Miraculously, he convinced Siddal to sit for his painting of The Twelfth Night as Viola:

And we say miraculously, because back in the day there was still a lot of stigma surrounding artists’ models. Siddal was also not from the same echelon of society as these lofty Raphaelites, but a working class woman. She was literate, and fostered a deep passion for poetry and the arts – but while these men were getting their education at the Royal Academy of the Arts, Siddal was home-schooled by her mother and allegedly got her first taste of English poetry from a stick of butter – which happened to be wrapped in a torn out page from the works of poet Alfred Tennyson; a major influence on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Siddal must’ve felt terribly divided at the proposition to model for Deverell. On the one hand, here was a chance to plunge into the very world she loved. After all, she too now aspired to be a poet – and she could also make a heck of a lot more money in one sitting than she could fitting customers’ heads at the millinery. On the other, it could tarnish a young woman’s reputation forever.

With approval of her parents, Siddal took the risk and started earning a handsome wage as a model. Soon, her face was on Pre-Raphaelite canvases everywhere, which were raising more and more eyebrows. How dare they paint Jesus as a lowly, secondary figure? Pre-Raphaelite co-founder John Everett Millais’ Christ in the House of His Parents was declared blasphemous. It even inspired hate mail from Charles Dickens, who called his depiction of the Virgin Mary “horrible in her ugliness.”

It was Ophelia, also by Millais, that shot the model to new stardom in 1851-52. Today, historians believe they’ve actually found the precise location at Hogsmill River where he painted en plein air – a tangle of luscious greenery and symbolic flowers.

That was the easy part. Allegedly, when Siddal was posing for Millais in a billowing antique wedding dress, she nearly froze to death. You would, too, if you had to submerge yourself in icy bathwater, heated only by a few flickering candles underneath the clawfoot tub. Millais was so engrossed in his painting – and Siddal was so afraid to complain – that he didn’t notice the candles had gone out until it was nearly too late. Siddal was lucky to recover from the pneumonia, which would be a precursor of her health troubles to come. On the insistence of her parents, Millais paid her doctor’s bills.

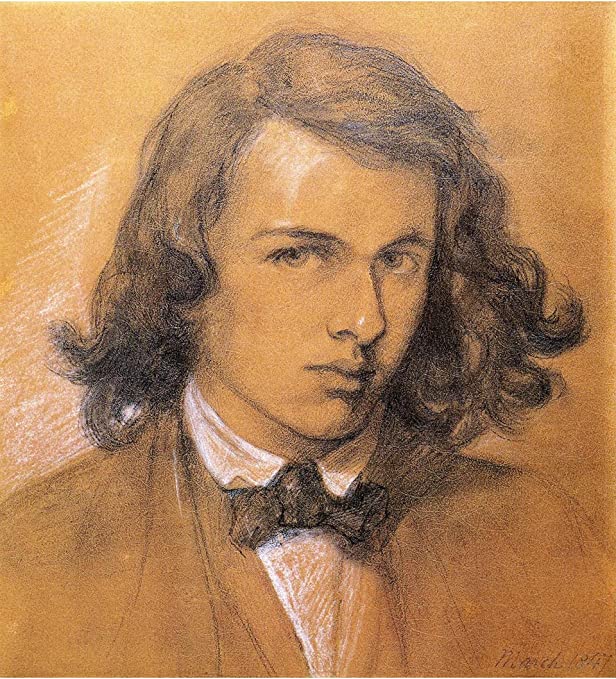

How much we wish we could say it was smooth sailing from there; that Siddal seamlessly transitioned from muse to professional artist and lived happily ever after. Instead, she met artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who was a celebrated genius of Pre-Raphaelites, wrapped in a heartbreaker, wrapped in a train-wreck. While there was give-and-take with their professional and romantic relationship, most scholars agree: Dante was, well, difficult. With his famously dark, brooding good looks, he suffered from a bit of an ego problem too.

On the one hand, he helped her become even more integrated into the worlds of poetry and art, providing her with supplies for both, even though he often wrote off her poetry as “sad and sentimental and self-consciously pathetic.”

A Silent Wood

O silent wood/ I enter thee / With a heart so full of misery / For all the voices from the trees / And the ferns that cling about my knees. / In thy darkest shadow let me sit / When the grey owls about thee flit; There will I ask of thee a boon, / That I may not faint or die or swoon. Gazing through the gloom like one / Whose life and hopes are also done, / Frozen like a thing of stone I sit in thy shadow but not alone. Can God bring back the day when we two stood / Beneath the clinging trees in that dark wood?

Elizabeth Siddal’s poem, “A Silent Wood”

Despite Rossetti’s saltiness, the lovers moved in together, becoming recluses from the rest of the world in their passion. We have to admit, their pet name for one another, “Guggums,” was also pretty damn cute.

Rossetti created hundreds upon hundreds of sketches and works of Siddal – much to the chagrin of his family. “He feeds upon her face by day and night,” observed his sister, Christina. “And she with true kind eyes looks back on him.”

Rossetti even prompted her to change the spelling of her name, and started controlling who she could and couldn’t sit for. Siddal’s health grew weaker, while Rossetti’s attentions went towards his work, and that of other women.

Siddal did have an influential friend looking out for best interests however, in art critic John Ruskin. He was one of the first to praise the Pre-Raphaelites as mavericks – not to mention, he gave Siddal credit where credit was due.

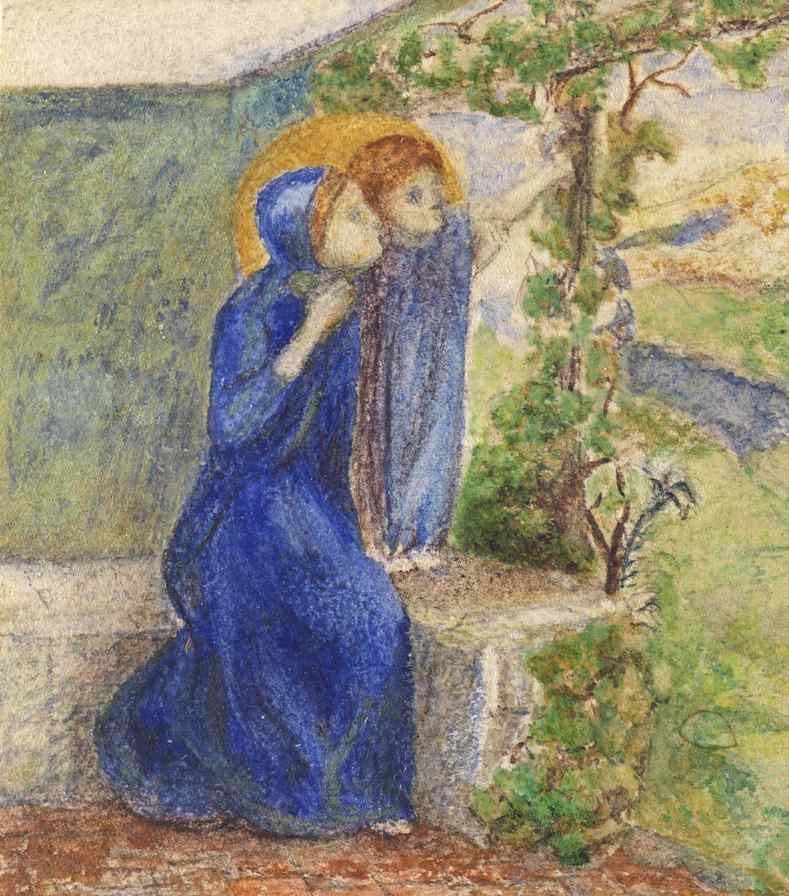

Ruskin proclaimed her a “genius” given that she’d essentially learned all of her painting techniques by looking over Rossetti’s shoulder, and agreed to become an official financial patron of her artworks, which we would argue begin to somewhat anticipate the dappled brushstrokes of Impressionism…

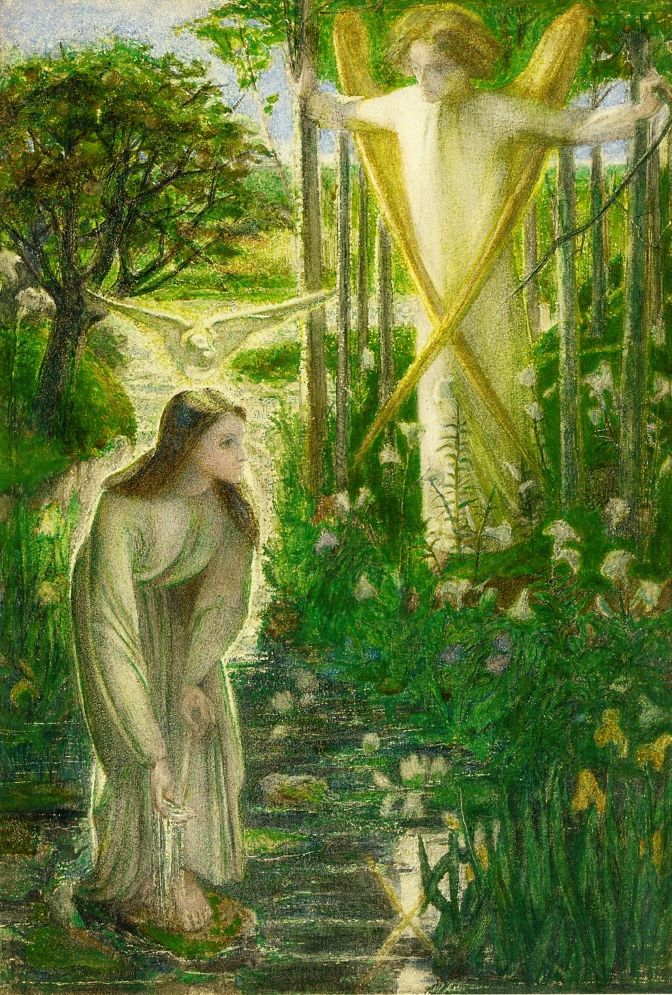

One look at a Rossetti painting from the period, and you can tell they were working side by side…

The Annunciation by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, c. 1855, with Elizabeth Siddal as the model for the Virgin

The sponsorship should’ve been a proud moment for the couple – instead, it just got kind of…awkward. Ruskin wanted to sponsor Siddal, but not Rossetti, and likely due to a messy Pre-Raphaelite love triangle between Ruskin, his wife, and Millais (who stole her heart).

Ruskin then convinced Siddal to travel to Europe, where he hoped the weather may improve her health. Sadly, it seemed to do the opposite, if anything because upon return she found out Rossetti was having an affair with another red-haired model, Fanny Cornforth, whose depiction as Judith in one of Rossetti’s paintings is almost too perfectly on the nose with situation. In a fit of anger, a heartbroken Siddal destroyed all of his sketches of Cornforth.

We might mention that Siddal wasn’t the only red-headed muse on the Pre-Raphaelite scene. There was a handful of strong, striking ladies whose contribution to the movement is only just getting the recognition it deserves through recent exhibitions like The Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood at the National Portrait Gallery. A book of the same name was written by Jan Marsh in the ’90s, paying tribute to these gifted and ambitious women. While Siddal might have found a love rival in Fanny Cornforth, she found support, inspiration and friendship in numerous independent women that floated in the same circle, aspiring working class women artists that found a leg up through modelling.

Tumultuous romance, drama between muses – these aspects are very real parts of Siddal’s story, but facets that have unjustly eclipsed the very real bravery of her own work, and that of the oft-forgotten Pre-Raphaelite “Sisterhood.” Yes, Rossetti defined Siddal. But Siddal defined hundreds of his canvases, as well as her own. Not to mention, she had to manoeuvre through the strange, quickly-evolving world of what it meant to be a celebrity-muse. “Each era endows the muse with the qualities, virtues, and flaws that the epoch [calls for],” explains Francine Prose in The Lives of the Muses: Nine Women & the Artists They Inspired. Hence, why Siddal’s decision to pose embodies a complex move towards both autonomy and objectification that we can still see in model-muses, though today we call them “supermodels.”

The latter enjoy arguably less of a stigma, but there is still a troubling bedrock beneath the glamour, says Prose, that comes with the “self-destruction” that the public associates – even craves – from these women. Culturally, we are only just beginning to laud musedom as a choice.

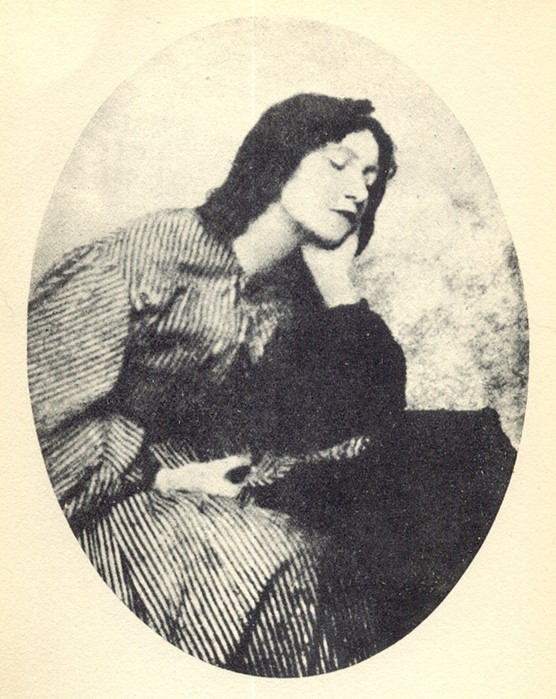

In 1860, the seemingly impossible happened: Siddal and Rossetti were married. They had already been living together for a decade, but Siddal’s lower social stature had been seen as an embarrassment by Rossetti family. If anything, the marriage might’ve been a gesture of pity; Siddal was so fragile, she had to be carried to church.

Today, historians believe Siddal also may have suffered from tuberculosis, or an eating disorder like anorexia, which wasn’t to be classified until 1873 by one of Queen Victoria’s personal physicians. Victorian England was a strange time to be a sickly woman. To appear deathly pale was fashionable and fetishized. Tragically, Siddal lost not one but two babies, and the onset of an arguably fatal depression.

One day in 1862, Rossetti noticed Siddal looking particularly ill. Regardless, he went out to teach his night-class at the Working Men’s College, and to have dinner with a friend. When he returned home, he found her overdosed on laudanum with a suicide note pinned to her chest, but destroyed it in order to make sure she received a proper Christian burial. She was just 33-years-old.

The end of one chapter on Lizzie Siddal, no doubt – but also, the beginning of an eerie celebrity. For the public, there was nothing more tragic than the loss of an already tragic muse. That Siddal had overdosed on laudanum – a drug made from poppies – also felt like a dark coincidence; in Millais’ Ophelia, the painter depicted Siddal clutching poppies and violets as symbols of death. As for Rossetti, who was always one for grand gestures, added to the sense of public drama by tossing his poems in her coffin at the funeral. “I have often been writing at those poems when Lizzie was ill and suffering,” he said, “and I might have been attending to her, and now they shall go.”

As time went on, Rossetti became more and more paranoid, and believed Siddal was haunting him. A hunch that was happily encouraged by the growing Spiritualist movement, which popularized the use of seances to communicate with the dead. It was also around this time that his own visual and financial health were failing, and in an act inspired by desperation, or selfishness – we can’t say for sure – he did the unthinkable: he dug up Siddal, to take back his poems for publication. (Amazingly, he did it all legally.) Unsurprisingly, it became a spectacle; papers swirled with headlines about how even in death, Siddal’s beauty endured. Rossetti even claimed that her golden hair continued to grow.

The macabre elements of Siddal’s life are undeniable. Iconic, even. No other woman in art history, no other person, can boast of so powerfully portraying the likes of Ophelia, Princess Sabra, and – in a gesture oh so fitting to Rossetti’s personal narrative – Beatrice. He completed this painting of her as the guide of Dante’s Inferno (his namesake work)…

As for Siddal, her work as an artist is only beginning to get the attention it receives; in the 1990s she received her first solo exhibition, and the aforementioned National Portrait Gallery show helped reorient her narrative towards her own contributions as a poet and painter.

Siddal and her Pre-Raphaelite “Sisterhood” brought new life to poetry, painting, and even embroidery, to say nothing of their impressive navigation of the business of the art world when it was exclusively a man’s world. The Art of the Pre-Raphaelites by Elizabeth Prettejohn, and Jan Marsh’s Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood do an excellent job of reframing the Pre-Raphaelite narrative to show how women like Siddal were not just on the sidelines, but at the centre the movement – creatively, sentimentally, and monetarily. The effort to re-write Art History with women in picture, is still an ongoing effort.