Forget the great and gaudy Hearst Castle – why don’t they talk about Fonthill Castle? Now that’s a house worth seeing. Some might call him America’s first hoarder, but for any aspiring collector or lover of eclectic arts, Pennsylvania’s most underrated treasure is an astonishing visual treat at every turn, telling the story of a renaissance man who mastered the art of clutter.

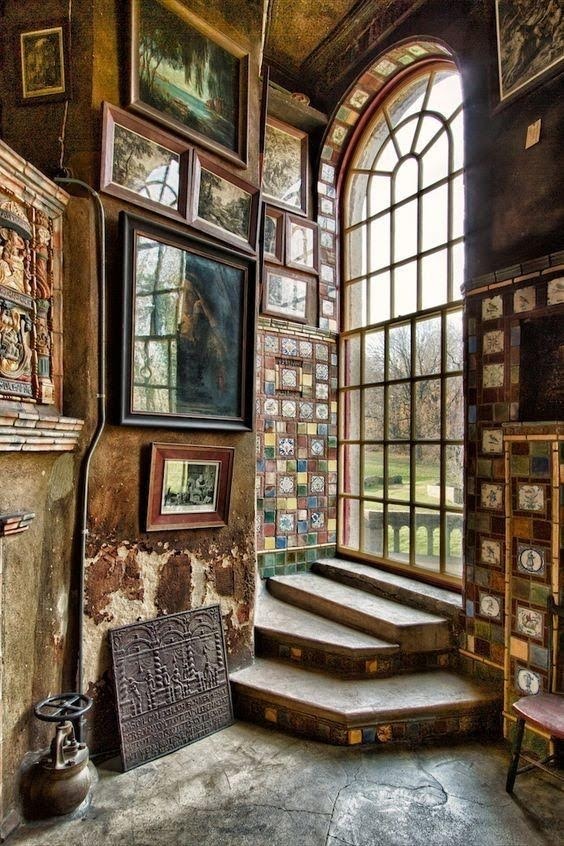

All of the stairs are crooked in Fonthill Castle and Henry Chapman Mercer liked it that way. He wasn’t technically an architect after all, he was an archeologist, a collector of artifacts and if you can’t already tell from these first glimpses into his home, he was also a talented tile-maker…

He was mad about tiles and spent much of his time learning ancient techniques of ceramics and tool-making. You could say Mercer was a nostalgic man, who believed that industrialism was destroying American society – but that didn’t stop him from winning the respect of major industrialists, like Rockefeller and Henry Ford. Rockefeller commissioned his ceramics for his own estates and Ford created a museum after being inspired by Mercer’s collection.

His Harvard classmate called him a “man of unusual character and imagination. Handsome, winning, interesting—and odd.”

A passionate eccentric born into family wealth, Henry strove to preserve and revive lost crafts and founded numerous historical societies. He was a leader in the arts & crafts movement, an outspoken opponent of the plume trade and an avid dog lover. In a nutshell, he sounds like our kinda guy.

More than that however, we’ll never know. Mercer was a private man and destroyed much of the personal information that might have given historians a window into his life. He never married and had no children.

When he died in 1930, he left Fonthill Castle in the trust of his housekeeper and her husband. It was Mercer’s wish that the couple reside in the house consisting of 44 rooms, 32 stairwells, 200 windows and 18 fireplaces, and they they open it up for tours as a museum of decorative tiles and prints. His loyal housekeeper, Mrs. Swain, lived there until her death in 1975.

Henry Chapman Mercer’s “Castle for the New World” was built entirely out of hand-mixed concrete, poured-in-place, but one could easily mistake it for a Medieval or Gothic fortress. The deceivingly austere exterior gives you no indication of the eclectic menagerie that waits inside. In fact, the interior of Fonthill was originally painted in pastel colours, but time has faded all of Mercer’s originally intended colours.

But why would an anti-industrialist choose to build the walls of his castle with such a crude material as reinforced concrete? After the Great Boston Fire of 1872 destroyed a prized collection of medieval armour that belonged to his Aunt, he vowed never to allow his own collection to suffer the same fate. Concrete would make sure of that. When the fireproof castle was completed, he lit a bonfire on the roof to prove it.

Mercer then filled his new home with expressions of his travels and passions, covering it floor to ceiling with his own hand-crafted tiles and making intricate mosaics with thousands more he had collected from Persia, China, Spain and Germany. While creating the castle’s elaborate interiors, he allowed his beloved dog Rollo to walk over the wet concrete, leaving not just Mercer’s tile work, but his faithful retriever’s paw prints, forever embedded in the design of Fonthill.

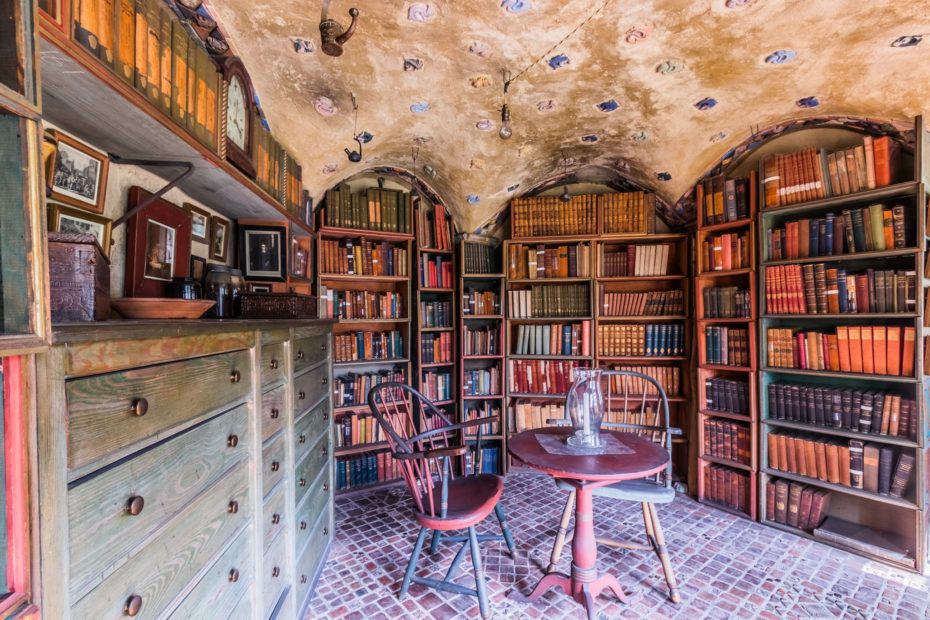

Every room in the castle looks like something out of a fairytale. There are some 7,000 prints he collected from around the world hanging on the walls. Its bookcases hold around 6,000 volumes, almost all of which are personally annotated by Mercer himself with handwritten reviews and comments about each book. Fonthill essentially advertised Mercer’s talents and tastes, and he even built his own tile factory on the grounds of the estate. But alas, the fruits of Mercer’s collecting habits was never going to be able to fit in just one castle.

Enter the Mercer Museum, built in the same style as Fonthill, designed entirely by Mercer. And if you thought his home was cluttered, wait until you see his museum. Located on the other side of Doylestown, PA, a good portion of which is now better known as the “Mercer Mile”, this was the other castle that would house his extensive collection of objects representing everyday life – all before industrialisation of course.

Henry believed objects had the power to tell stories about humanity, and his insatiable thirst for knowledge, discovery and exploration is reflected in this remarkable exhibition of everyday things. The curation is no accident either. Exhibits on crime & punishment right next to education.

There are 6 floors, 55 rooms and alcoves full of interesting conversational relics to explore. Spinning wheels, carriages, boats and sleds are suspended in mid-air and rooms are dedicated to early American tools for various trades. There’s even a fully-stocked general store from the 1860s.

The Mercer museum is filled with objects that were regularly seen in American homes just over a century ago, but today, are rare, unknown and foreign to us. The rapid progress of society has made them extinct and the knowledge of how to use them is all but lost. Mercer saw this coming in the late 1800s and made it his mission to save these objects for future generations inside of his fire-proof concrete castles.

It’s thanks to him that we can envision the past two centuries through his relics, many of which are the only surviving examples of their kind in the world. Both as overwhelming as each other, Fonthill Castle and the Mercer Museum are well worth the 45 minute drive north of Philadelphia. If you get an early start, it’ll make an unforgettable day trip from New York City, under two hours drive away.

You think you’re a collector until you’ve seen Henry Mercer’s world.

More information about visiting Mercer Museum and Fonthill Castle here.