Today, we meet a heroine by the name of Belle da Costa Greene. Under the honey-hued lights of Manhattan’s Morgan Library, she became the guardian of the world’s greatest cultural treasures: not one but three Gutenberg bibles, illuminated manuscripts, originals by Da Vinci, Mozart, Michelangelo, and others – the list goes on (in its very own article, we might add). She was also a Black woman who made it to the top of the archival game in 1905. Over the last 114 years, the “Morgan” became a living compendium of works that’ve bookmarked human history, and all thanks to Belle. This is her story.

Belle was the daughter of the first Black man to graduate from Harvard, but her relationship with her father iced over when he left (but never separated from) her mother Genevieve, and started a completely new life in Siberia as an American diplomat. He had left them with three choices: shame, denial, or reinvention. Belle and her mother changed their last name to distance themselves from him, and took on names with inklings of European ancestry. Genevieve became the Dutch-y Van Vliet, and Belle subbed her real middle name for the Portuguese-sounding “da Costa” to cloud her ethnicity in mystery. A tragic reality, but one Belle knew she had play to her advantage to break through the glass ceiling as a woman of colour at the turn of the century.

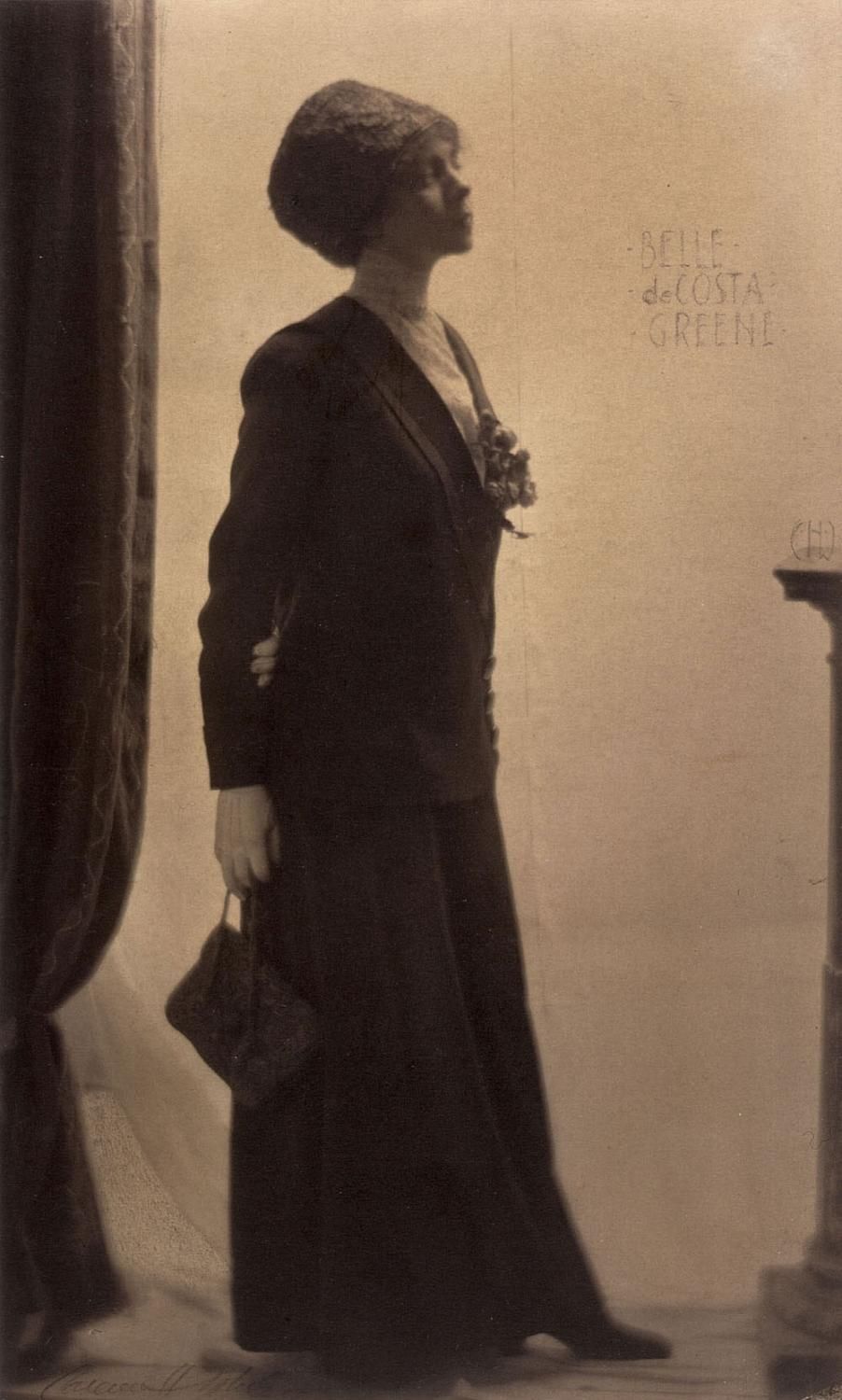

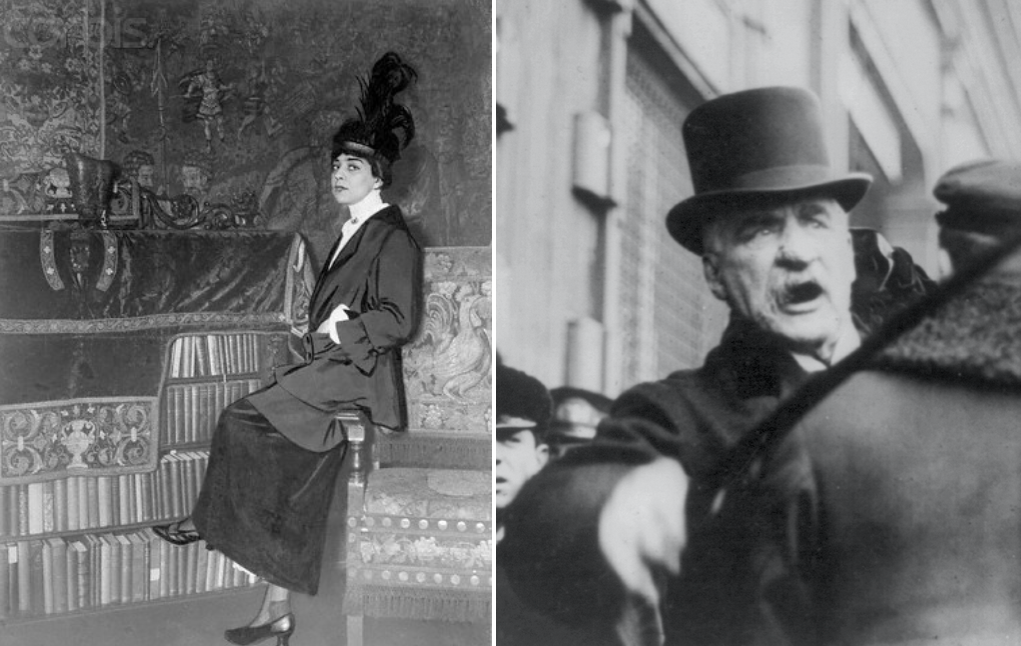

First, Belle got a job as a librarian at the Princeton Library in New Jersey, where she immediately started challenging the cliché that librarians were grumpy, musty, and often men. “Just because I am a librarian,”she said, “doesn’t mean I have to dress like one.” Aside from being sharp as a whip, Belle was a sight for sore eyes; papers recall her as a “dark haired woman of great beauty” who kept her personal life a mystery (aka, professional. Heaven forbid!) and always had a quick remark at the ready in one of her tremendous, feathered hats. Check her out “In The Limelight” in the upper right:

It was at Princeton that she met Morgan’s nephew, Junius, who connected her to his legendary uncle in 1905. A 1949 Time article recalls the moment she was hired:

Seated massively at his desk that day in 1905, John Pierpont Morgan seemed lost in thought. He hardly even bothered to look up when his nephew Junius appeared before him with a slim, grey-eyed girl in tow. “Uncle,” said Junius, “this is Miss Greene.” Thereupon the Great Man grunted a “How d’you do?”—and the interview was over.

Thus, scarcely out of her teens, “quaking with fear and shaking like an aspen,” Belle da Costa Greene began her career as head of the Pierpont Morgan Library. She was not to quake or shake for long. In time she became famous in her own field….

Firstly, let’s debunk the image of Belle as a doe-eyed, shaking teen. This woman was a powerful networker, who would go on to dazzle at European salons and even pose for Matisse. She was 26 when she arrived at the library, and probably intimidated – but she was also determined to make sure Mr. Morgan had the most impressive collection in the world for his library, and could hold her own with him.

“Although she [worked] with Morgan only seven years before his death in 1913,” explains the Library, “Greene transformed [his] collection and quickly became a leading figure in the rare book world. For example, in 1908—during her first trip to Europe—she famously orchestrated a secret pre-sale deal to secure a group of coveted volumes printed by William Caxton.” There was a kind of affection and flirtation between Morgan and Belle, for sure. But in the end, it was always superseded by their respect for one another and building up this incredible library.

Oh, how we love to imagine the epic scenes of Belle shutting down a bunch of crusty antique dealers at a turn-of-the-century auction, and returning to put her feet up at the veritable palace the library was turning into…

When Morgan died, he left Belle the equivalent to $1,267,508 today in his will, and she continued to work at the Library until her retirement in 1948. In the last two years of his life alone, it’s said that Mr. Morgan and Belle had invested the equivalent of almost $900 million in rare books. She was left as the guardian of quite a collection.

“According to Ardizzone, who teaches American studies at the University of Notre Dame,” explained The New York Times’ Caroline Weber in 2007, “[Belle] wanted above all to make ‘the rare books she prized so highly available to the public, not locked in the vaults of private collectors’ — and [in] 1924, when Morgan’s library became a public institution and Greene was named its first director, she celebrated by mounting a series of exhibitions, one of which drew ‘a record 170,000 people.'” She was classy, but never elitist. One for the books, indeed.

Biographers have had a famously hard time writing about Belle, who passed away two years after she retired. After all, how can you reconstruct the life of someone who practically burned all their papers on their death bed? Belle never married, but we do know that, for a time, she was madly in love with a dashing Russian art collector named Bernard — a relationship whose traces leave glimmers of the passionate woman she was in her private life.

The two of them must’ve made a great, albeit clandestine (he was married) power couple, frolicking across Italy, Paris, and Munich for treasures. He was also the only man to meet her level of cool, if we may say so. As in, chilling-with-Cole-Porter-on-a-gondola level cool. Catch him centre with the shades:

“Oh! B.B. daarrling, how I long to be with you,” she wrote him, “and [for you] to ask me if I remember that night [in Munich]. Do you remember that one wonderful night in my room with the funny feather mattress?” For historians, these words were a rare window into Belle’s heart. Even more telling, perhaps was one of the loveliest presents she sent him: a sultry, dignified mini-portrait of herself looking like an Egyptian queen. It’s certainly the way we like to remember her today:

Still, Belle’s greatest romance was with the literary treasures she helped preserve at the Library. Her hard work is why we can walk into the gilded library today, and not just observe history, but relive it. She is a reminder of the strides and unsung stories made by so many Black women in relatively niche professions – a reminder that activism also lives in the library.

Learn more about visiting the Morgan Library here.