You may hear it, before you see it. The gentle trotting of hooves backdropped by the sounds of New York City’s JFK Expressway. Even locals do a double take when they cross paths with a member of the Federation of Black Cowboys. When they ride, they tell the true story of the Wild, Wild West: that it was built by Black cowboys. In fact, an estimated one in three cowboys was a person of colour in the 19th century. It’s an often unsung legacy, and one that lives in big city Black cowboy clubs, working Black ranches, and luxury label-featured organisations and entertainers. But what did it really mean to be a cowboy in 1890? What about today? We spoke with Ron Tarver and John Ferguson, two photographers who have spent extensive time in Black cowboy communities – either growing up in them, or gravitating towards them from across the Atlantic – to document their story. Spur up, folks.

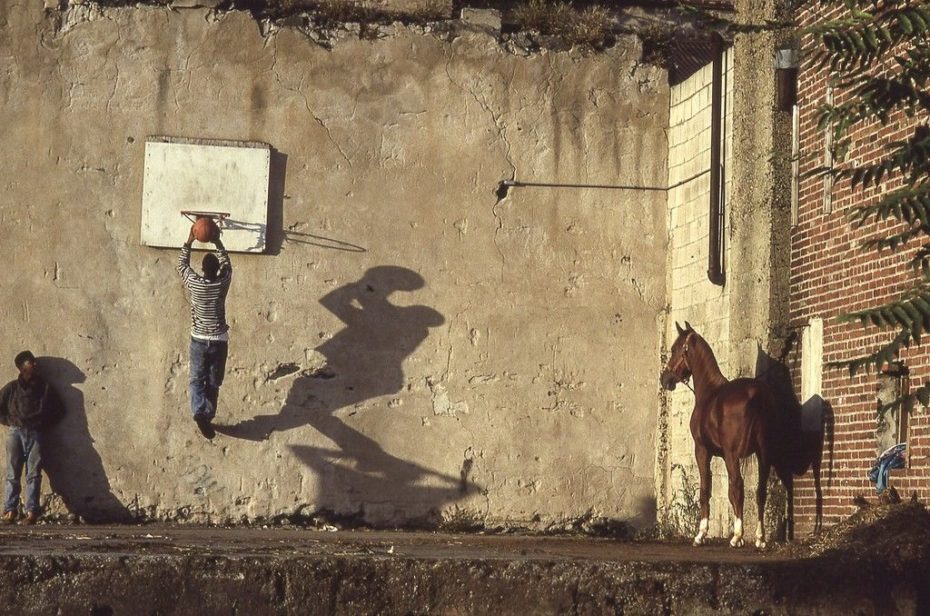

© Ron Tarver, Courtesy Robin Rice gallery, New York

Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist, Ron Tarver, grew up in Oklahoma, where his grandfather was a working Black cowboy, “driving cattle in a small town near Tulsa,” he tells us by phone from Philadelphia. As a kid, the rodeo was like his playground. And while he doesn’t identify as a cowboy, he recognizes how that cowboy environment has shaped him. “Oh, I grew up hauling hay,” he laughs, “and herding cattle on our motorcycles.”

As a working photographer in the 1990s, Ron Tarver published his groundbreaking four year–long series of images on black cowboy life for National Geographic. “Not even thinking about the fact that it was a novel thing,” he says, “To me, these were men and women who just worked. It was their life.”

The Federation of Black Cowboys has about 40 members today and was founded in 1994. “There was a number of Black gentlemen in the community who loved the idea of riding horses and nurturing the historical settings,” says former FBC Vice-President, Rolly W. Curly Hall in a 2019 ARTE mini-documentary, “So we set out our goals to teach the children in this community.”

In that light, we begin to see what role a city-dwelling group like the Federation of Black Cowboys (FBC) plays in America’s greater black cowboy story: one born from a desire to connect with the past, and uplift the present. As day jobs to pay the bills, members work in all sectors, from healthcare to finance to social work.

In 2016, their lease with NY Parks Department ran out on Cedar Lane, the Queens stables they called home for 20 years. Even then, they charged on. The former-FBC VP Hall’s home and a smaller, nearby stable space are currently serving as the HQ, as they continue to participate in parades, block parties, and other community building activities. They even travel to North Carolina by horseback.

Award-winning British Black photographer, John Ferguson, first spotted a member of the FBC in Manhattan some 20 years ago. “It was a chance sighting,” he tells us when we telephone him in London. “I was just thinking, this is amazing. How does nobody know about this outside of this community?” The experience sent him on a quest to learn more about them and eventually, on a personal photographic search for the first cowboys of the ‘Wild West’, which he updates through an archive on Instagram, @theforgottencowboys.

“So I flew to America to find these cowboys,” he says, “I took two eight-week trips in six different states, from Oklahoma to Texas to Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico, for example. My biggest surprise was this realisation that not even within the African American community, did people know about this. It’s a fascinating, unbelievable history.”

When do you get to call yourself a cowboy, though? A real one? Our modern definition is so lacquered with John Wayne swagger, that it’s hard to know where the truth shines through. As it turns out, the very origin of the word cowboy is derivative of the racist use of “boy” when referring to black men. Take a moment to listen about that evolution in this clip from a PBS short documentary:

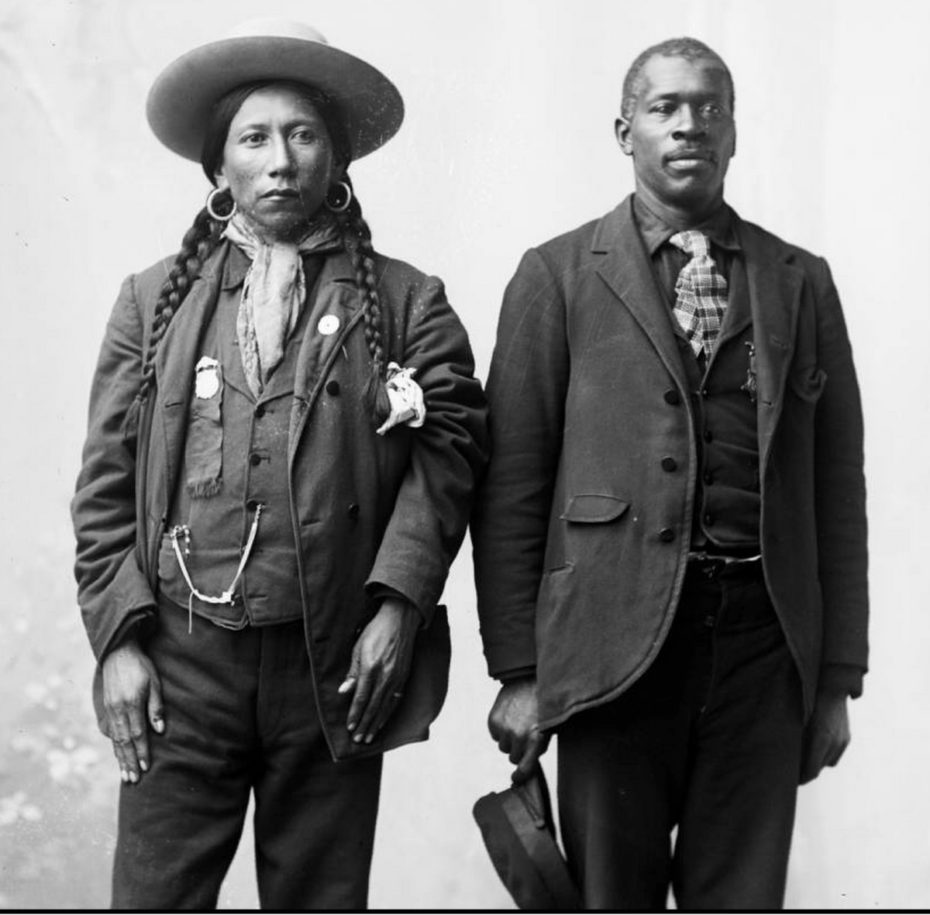

Growing up, many Americans are taught to see Manifest Destiny as this thrilling spectrum of possibility – a blueprint for bravery, with the occasional dash of Donner Party crazy. “The whole idea of taming the West,” says Ron Tarver, “well, basically, you’re just uprooting indigenous people.” The history of the Mexican-American cowboy, for example, is very complex, and interwoven with that of the black cowboy. It opens a layered conversation about integration, adaptation, and survival. This, too, has been superseded by cowboy whitewashing. Colonialism, but make it Marlboro.

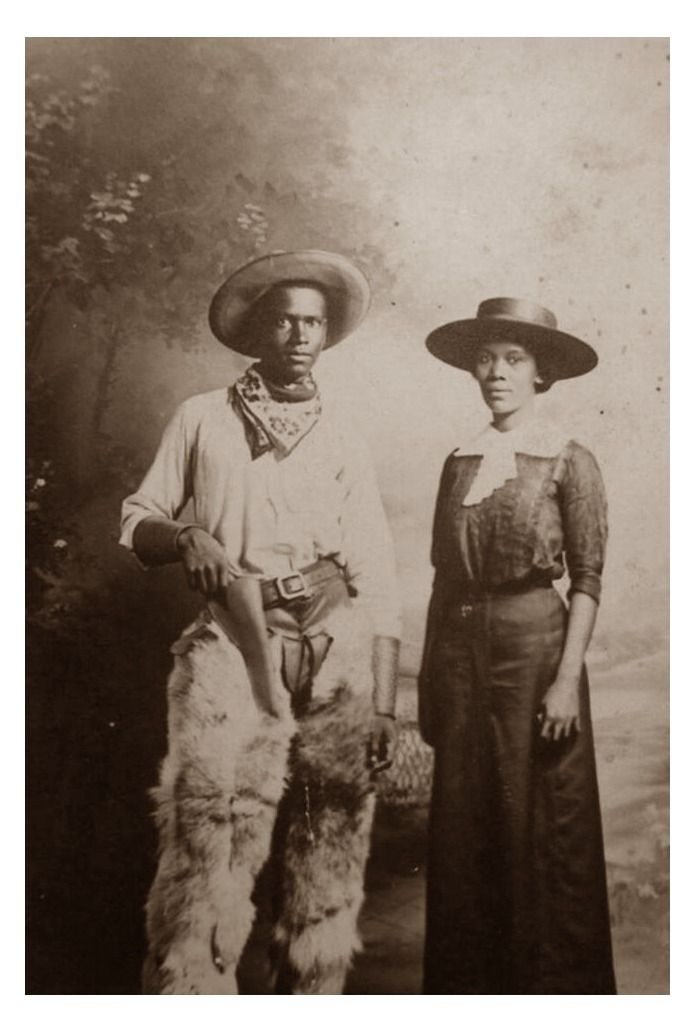

“Black cowboys did work that White people didn’t want to do,” says Tarver about the very beginnings of 19th century black cowboy life, “which is kind of the history of being black in America. Black and brown people came up –brown from Mexico – and would heard cattle from Texas to the north.” During the Civil War, many Southerns in battle also relied on Black ranch hands to keep things running smoothly, resulting in the latter’s honing of an amazing cowboy skill-set. “When slaves were freed, and a lot of slaves went to Texas during emancipation,” says Tarver, “they found work in ranches.”

They were cattle herders, fence painters, fiddlers, and cooks – gifted in whipping up a hearty meal of biscuits and sowbelly during the harshest conditions. “One guy talked about how in the winter, he’d have to break the pond’s ice so the horses and cattle could drink water,” recalls Tarver about a memorable story he’d heard at the O’Connor Ranch in Texas, “and as soon as he’d get through to the very last one, the first would be frozen over again.”

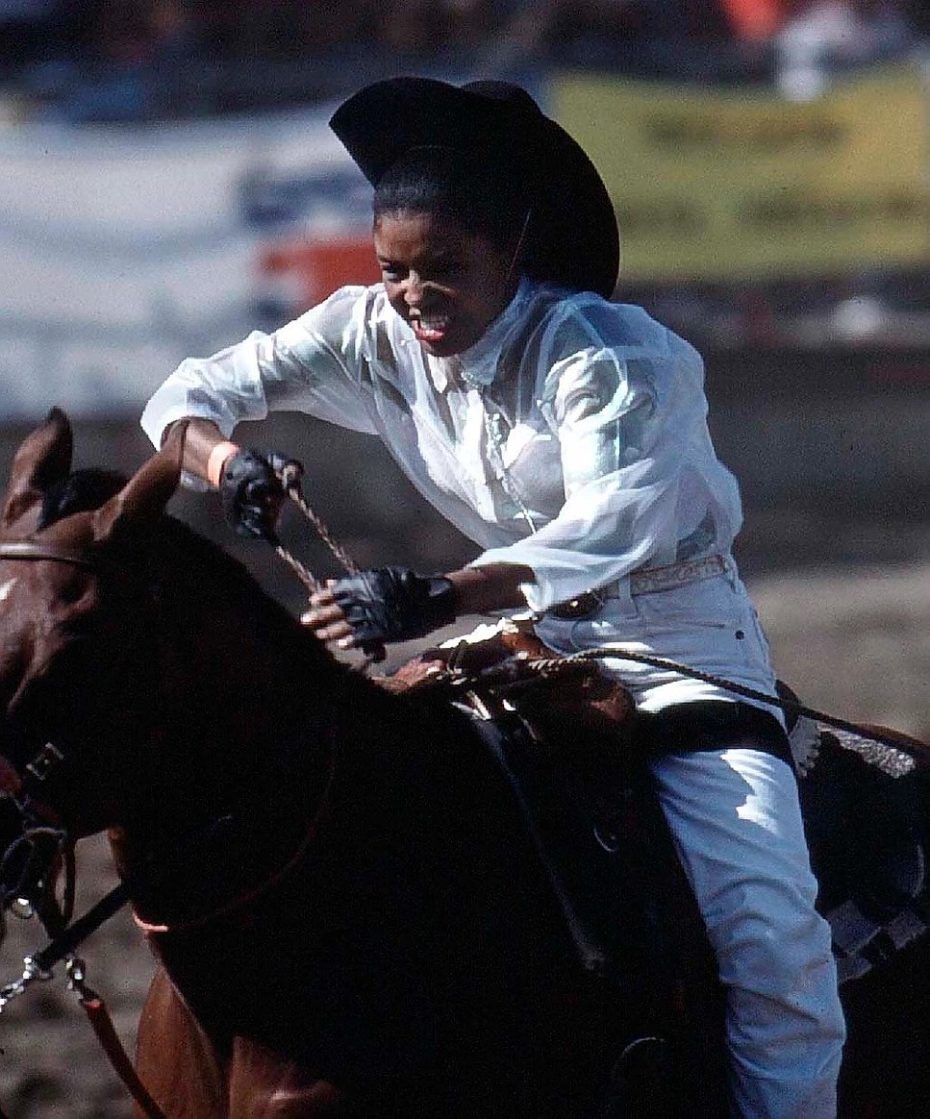

And don’t forget the Black cowgirls, either. “Women actually worked the ranch and developed skills similar to their male counterparts,” writes historian Cecilia Guitierrez Venable in Having a Good Time: Women Cowhands and Johana July, a Black Seminole Vaquera. She gives the example of Texas cowgirls Johana July and Henrietta Williams. July was a force to reckoned with, riding bareback with only a rope for a bridle. As a black Seminole Native American woman born in Mexico, she also found work as a translator at the US border. Williams, too, held her own as the proud owner of her own home and cattle.

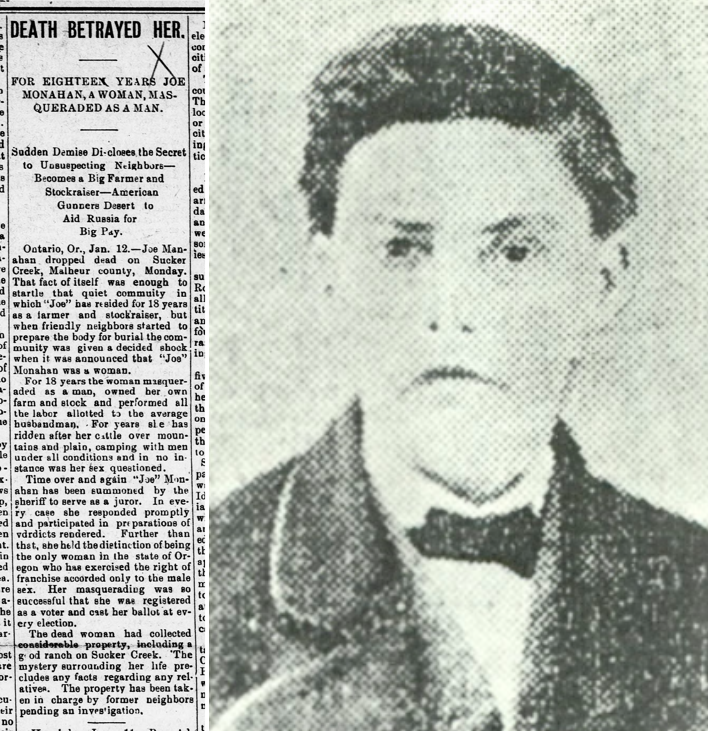

The onset of WWII also saw an increase in female ranch workers, but their stories were often bypassed to uphold that cruel double standard: do the men’s work, but do so invisibly. Imagine the surprise of the coroners upon the death of the Black cowboy “Little Joe Monahan” in 1903 – it turns out, he was a she, and for almost 20 years, lived as a respected male cowboy.

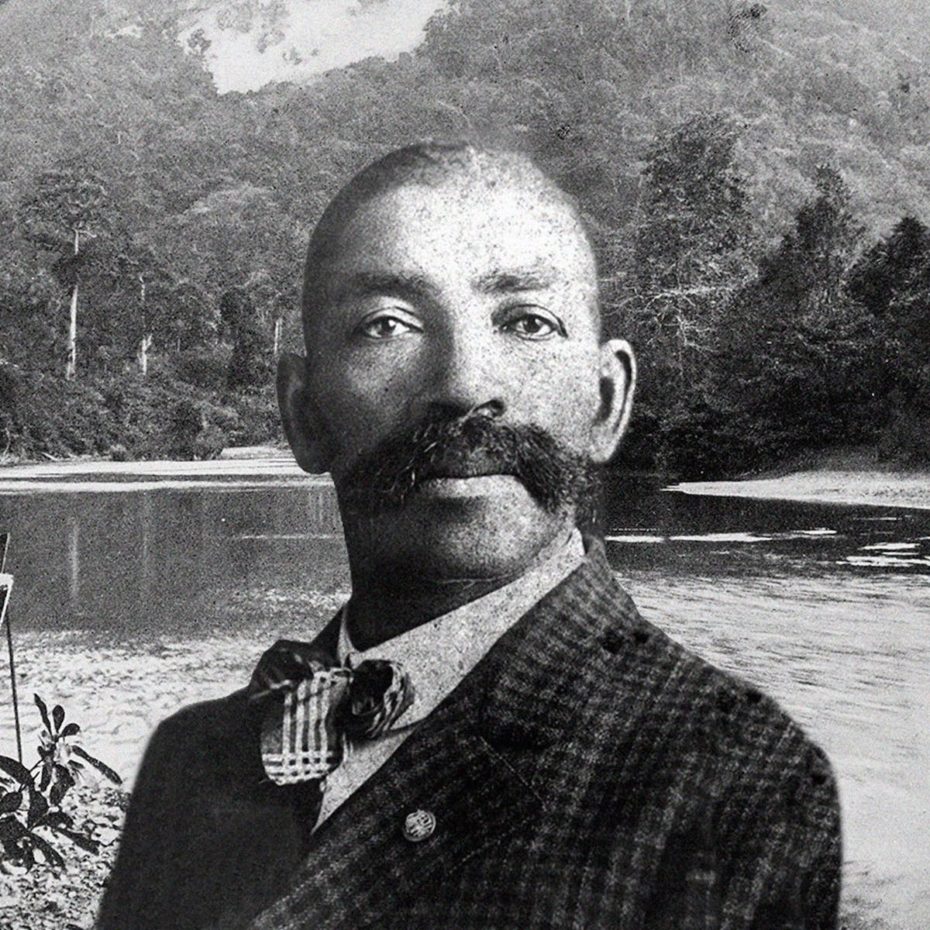

There is an amazing roster of untold black and brown Wild West stories. Do a bit of digging, for example, and we learn that the Lone Ranger was likely inspired by the first black deputy sheriff west of the Mississippi, Bass Reeves:

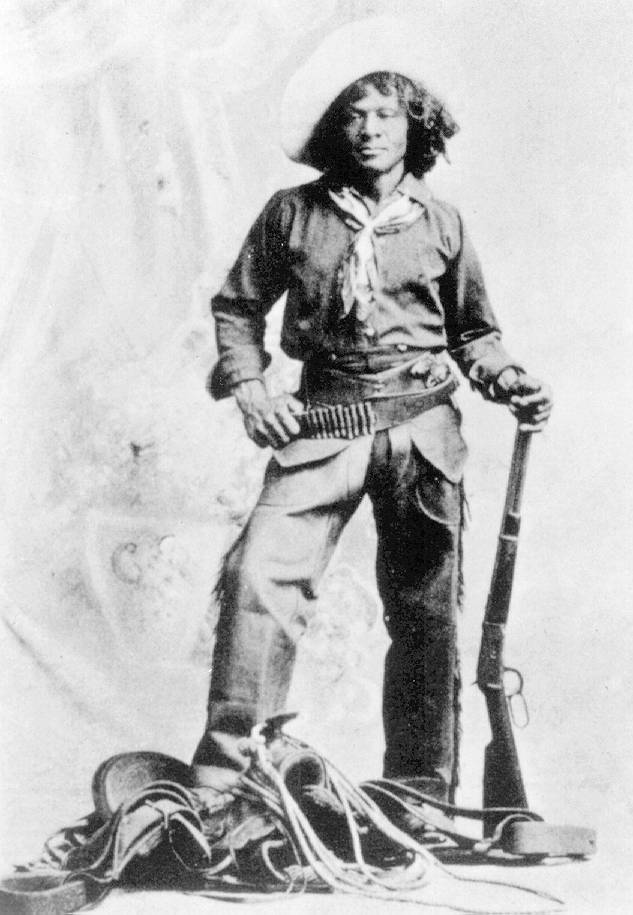

We learn about Nat Love, the former slave who became a self-trained, expert marksman and hero of the Wild West…

His story also speaks to the kinship that could be found between Native and African Americans; in 1877, he was captured by the Pima tribe while rounding up cattle. Death appeared to be on the horizon after he sustained over 14 bullet wounds, but the Pima decided to spare him out of solidarity – many of their own kin were also of mixed ancestry. They even offered to bring him into the tribe, but according to Love, he hopped on a pony and hightailed it to Texas.

We learn about black rodeo scene pioneers Jesse Stahl and Bill Picket. These two men are an early example of the showmanship and entertainment branch of the black cowboy universe:

Stahl, born 1879 in Tennessee, was a bold bronco rider – even riding one horse backwards in an act of defiance when judges once awarded him second place. His contemporary, Picket, was of Cherokee and Black ancestry. He started out his career on a ranch as a kid, and invented the technique of “bulldogging” – basically grabbing an animal by the horns – to catch stray steer. He performed on a global scale with the Miller Brothers’ 101 Wild Ranch Show alongside Buffalo Bill, and even appeared in some early motion pictures.

Clint Eastwood, Gary Cooper, Paul Newman – they all owe a huge debt to these stories. “Hollywood played a massive part in neglecting the African American presence in the western genre,” adds John Ferguson, “How many Westerns do you see growing up in the 1960s and ‘70s with a black cowboy?” Not many. That’s why, Ferguson and Tarver agree, these relatively new social club reincarnations of black cowboy life, from New York’s FBC to California’s “Compton Cowboys” and others, are powerful community building spaces for young people.

Now, the rural Black cowboy communities born from centuries old working ranches are perhaps different in that they were a product of the need to work. But in their down time, those cowboys also create wonderful community spaces. “There was this one cowboy party I went to,” says Tarver, whose photographs of the Black cowboys have been exhibited nationally, “and when I say party I mean, back in this barn like thing, maybe with a pool table and juke box, but everyone was dancing and it was like a hundred degrees at night. Kids are there, too. It was just amazing. You worked hard, and you played hard.”

And while cowboy rodeo events and trail rides remain a “niche” topic in mainstream white-centred media, keep in mind: these gatherings are not always groups of a few dozen people. “The first rodeo I walked into, I couldn’t believe how big it was,” says Ferguson, “I mean, you have massive arenas in America. There must have been about 20,000 black cowboy fans.”

Finally, says Ferguson, black cowboys are getting to create their own mythology– to step into that superhero role from which African Americans have so long been exempt in mainstream media.

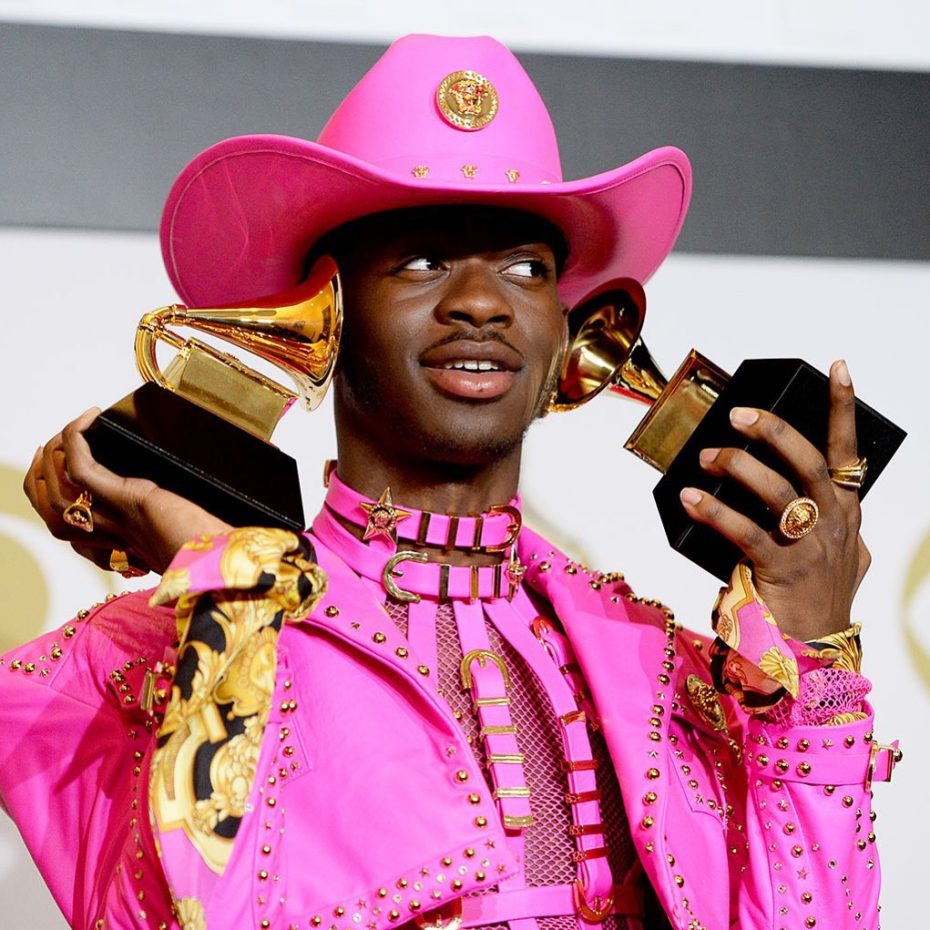

You may have caught wind of this new brand of #Yeehaw energy over the past two years. It champions inclusivity. It gives us the pop-country sounds of Kacey Musgraves, and the country-rap of queer, Black artist Lil Nas X. Now, it’s giving us an upcoming movie about Black cowboys in Philly, Concrete Cowboys, starring Idris Elba:

You may have also caught wind of the “Dread Head Cowboy” in Chicago this past week – the entertainer’s videos, riding horseback in solidarity with Black Lives Matter, have gone viral. “I think it’s good for kids to see that such a lifestyle isn’t unique to white people,” Tarver says of the media attention. “It’s good to keep that out front. Otherwise, being black in America comes to be seen as this urbanized existence. That’s not necessarily true. This breaks that myth. This shows young people that there’s more than one way to be black in America.”

Ron Ferguson seconds that sentiment. “It means that black people have a heritage they can hold onto other than the Slave Trade,” he says, “Everybody loves a cowboy. Everybody. Cowboys are sexy.” Especially right now – cowboys are having a major cultural moment.

So, how can you show support for black cowboy communities?

Follow related social media accounts, offer volunteer work, and donations to the Federation of Black Cowboys, Oakland Black Cowboy Association, Compton Cowboys and the Texas museums like the Black Cowboy Museum, est. 2017, and the National Multicultural Western Heritage Museum.

Continue to learn about black cowboy history with texts like Black Cowboys in the American West: On the Range, on the Stage, Behind the Badge – and take a moment with the Federation of Black Cowboys below: