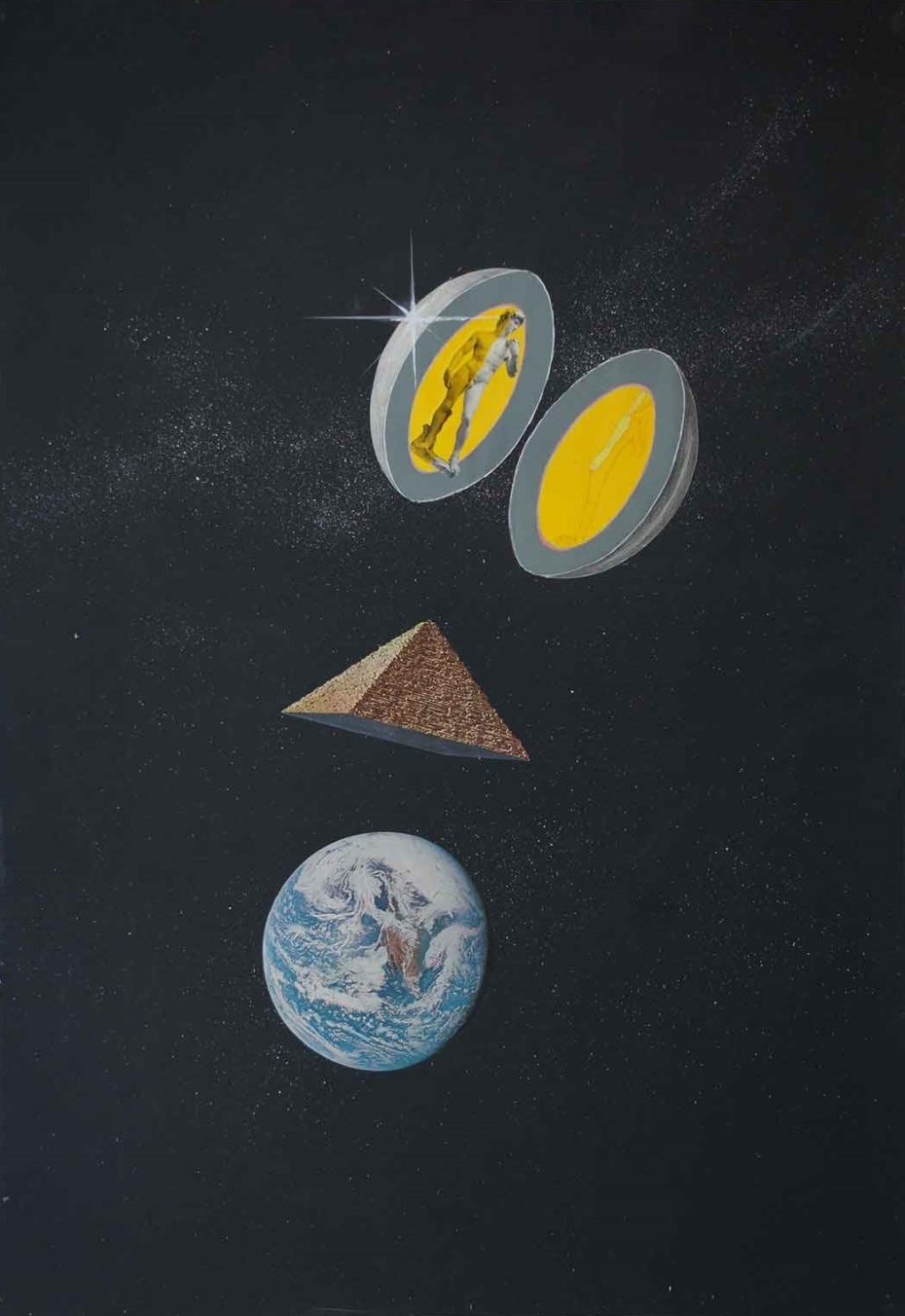

We were supposed to be living on the moon by now – at least, that was our trajectory according to the 1960s. Rockets had landed man on the moon and Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey glamorised high-definition visions of life in space. New worlds were within reach more than ever before, waves of peace and love and revolution were proliferating society and it seemed as though anything was possible. It was against this backdrop that in 1966, Florentine architecture students Adolfo Natalili and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia founded the Superstudio collective with the aim of creating an alternate model for life on Earth. Despite never having erected a single building, their conceptual works influenced generations and introduced architecture as a means of political protest. And if you’ve ever wondered about the source of all the dystopian, universe-merging mixed media art that emerged on the internet in the past decade, you’ve found it.

After the second World War, Italy was recovering from decades of fascist rule, and enjoying new economic growth. The country was going through rapid change, great industrialisation and rebuilding of cities. Its citizens were moving closer to new job opportunities in the cities, resulting in wider economic inequality. As a result of this surge in the production of new housing, architecture became the most popular academic major in Italy.

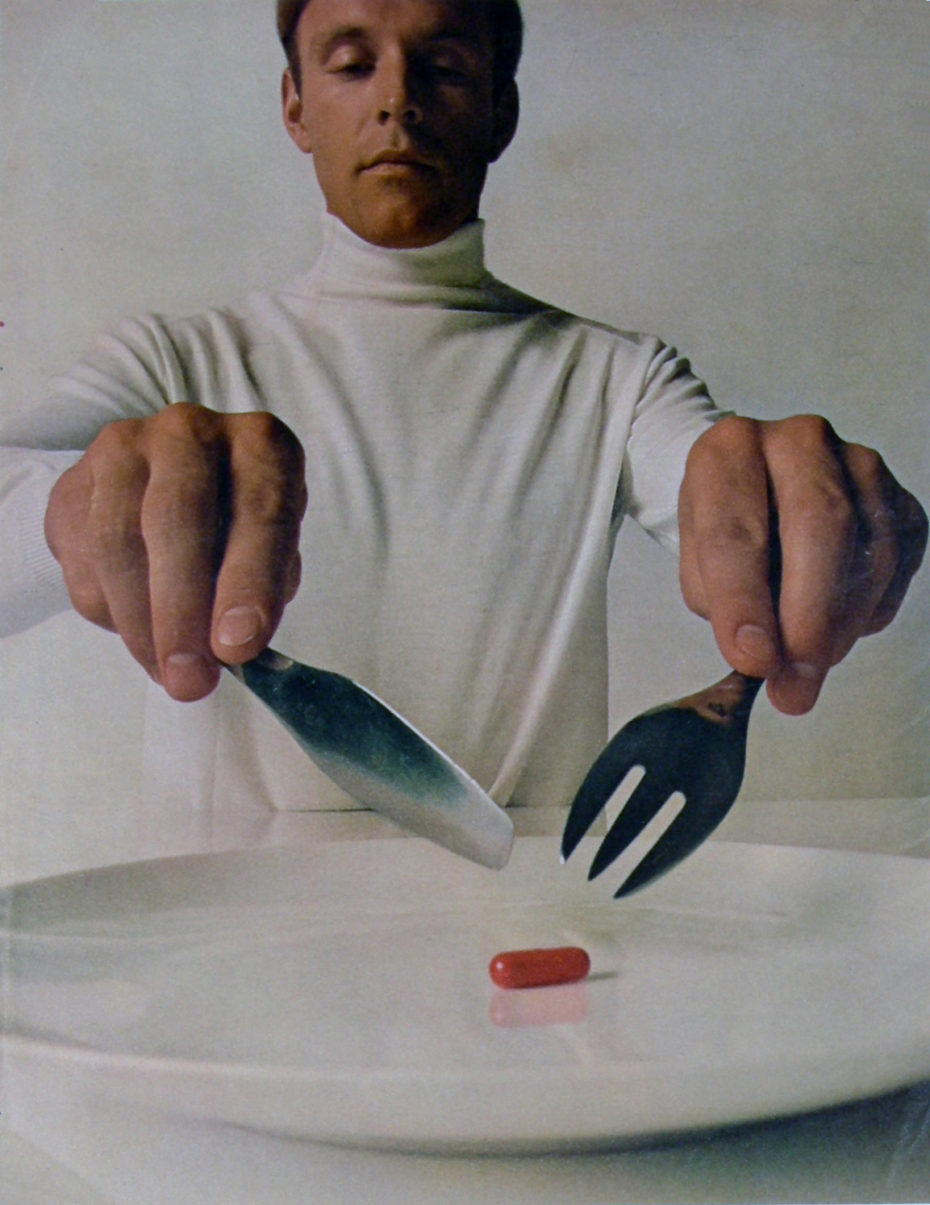

But the members of Supserstudio didn’t like the new houses that were being built, nor did they like the new shiny American consumerist culture. They thought Modernist designs were outdated and homogenous, and saw them as part of a system ingrained with social injustice and excessive consumption. In 1972, they made this presentation for a MoMA exhibition: “Italy. The new domestic landscape.”

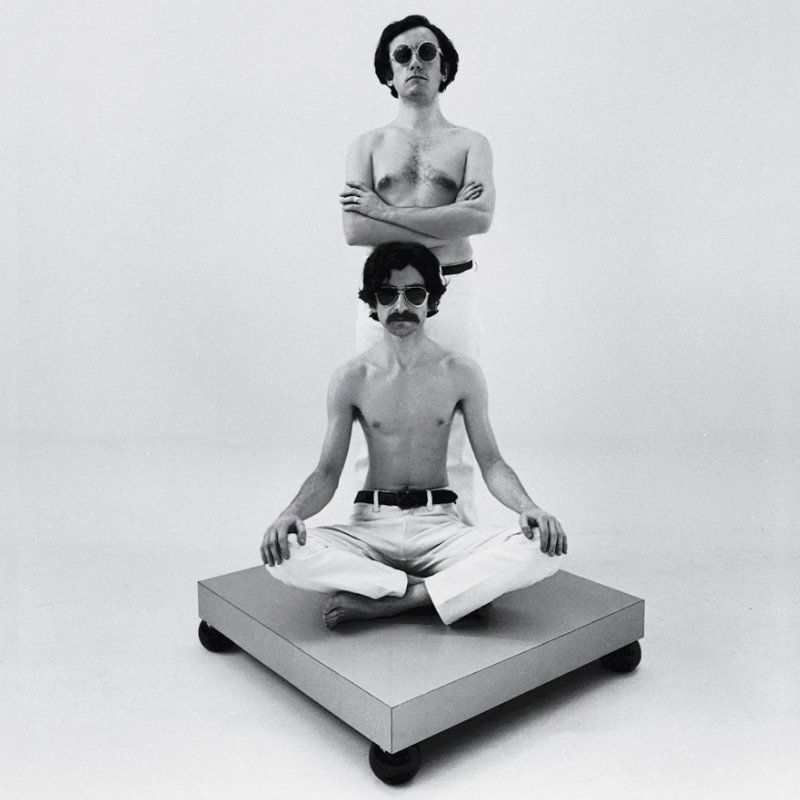

They would never actually construct a building, but they were throwing out ideas left front and centre, experimenting and unafraid to be bold. The creations of the collective were far out, philosophical, intangible and confusing. Aside all the conceptual, dystopian theorising, Natalini pointed out that they were “Of course…also having fun.”

“…if design is merely an inducement to consume, then we must reject design; if architecture is merely the codifying of bourgeois model of ownership and society, then we must reject architecture; if architecture and town planning is merely the formalization of present unjust social divisions, then we must reject town planning and its cities…until all design activities are aimed towards meeting primary needs. Until then, design must disappear. We can live without architecture…”

Adolfo Natalini, 1971

Superstudio’s collective believed all aspects of life had become ingrained with these political malaises, so of course, they humbly sought to create a model for an alternate life on Earth.

Seeing contemporary architecture as part of the problem, they created what they called anti-architecture; collages, films, and mind-boggling theoretical essays in order to kickstart philosophical and anthropological discussions as to how they could re-create the world that they were living in….

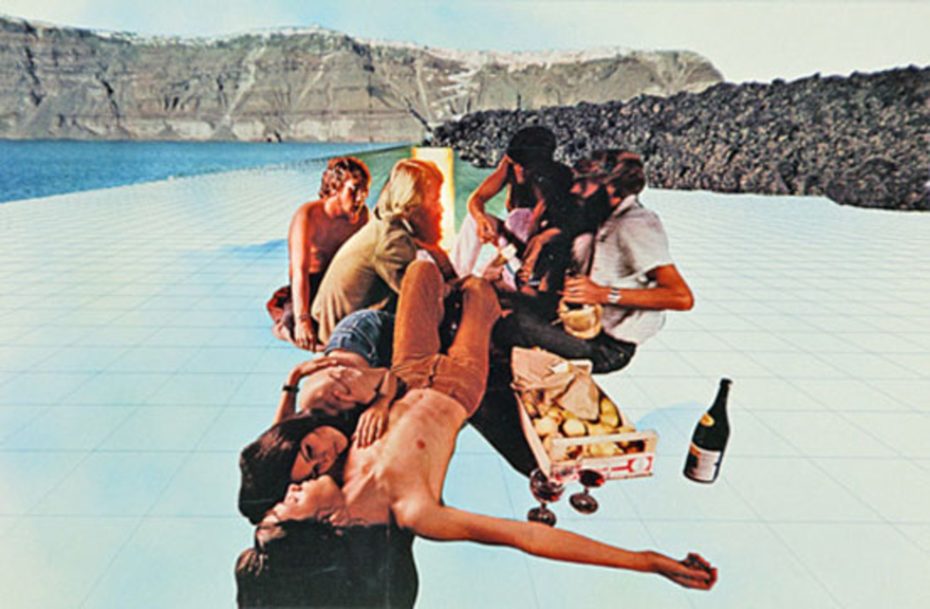

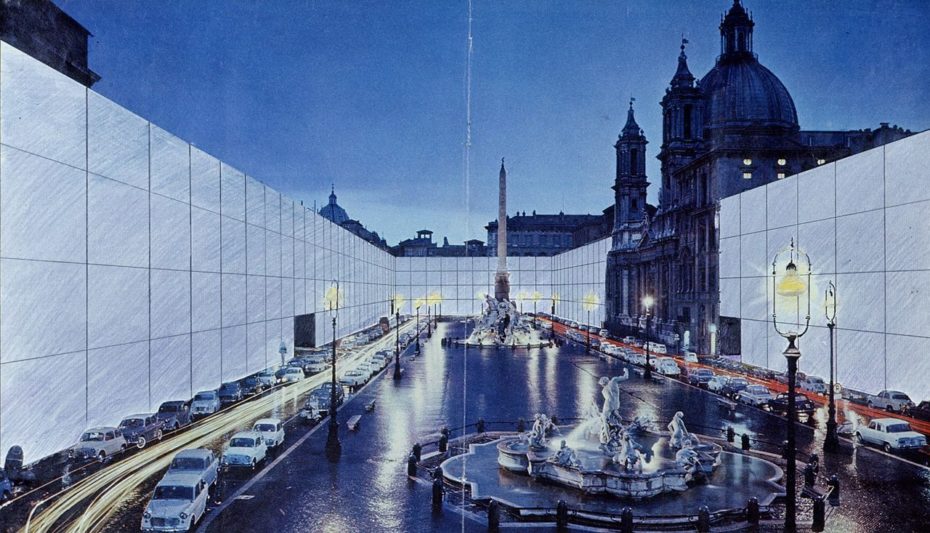

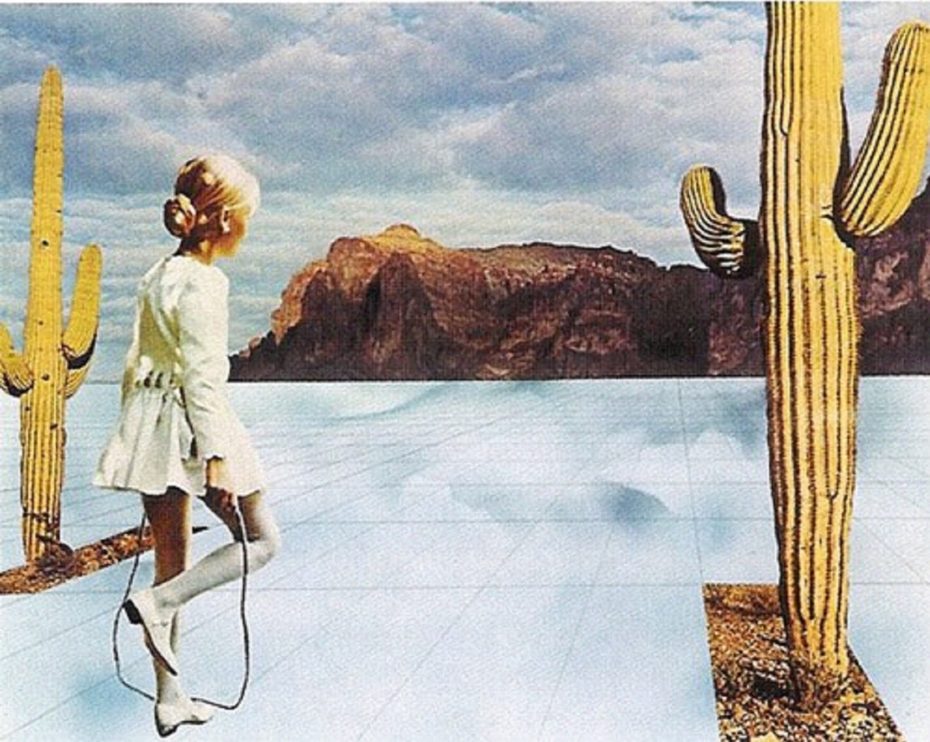

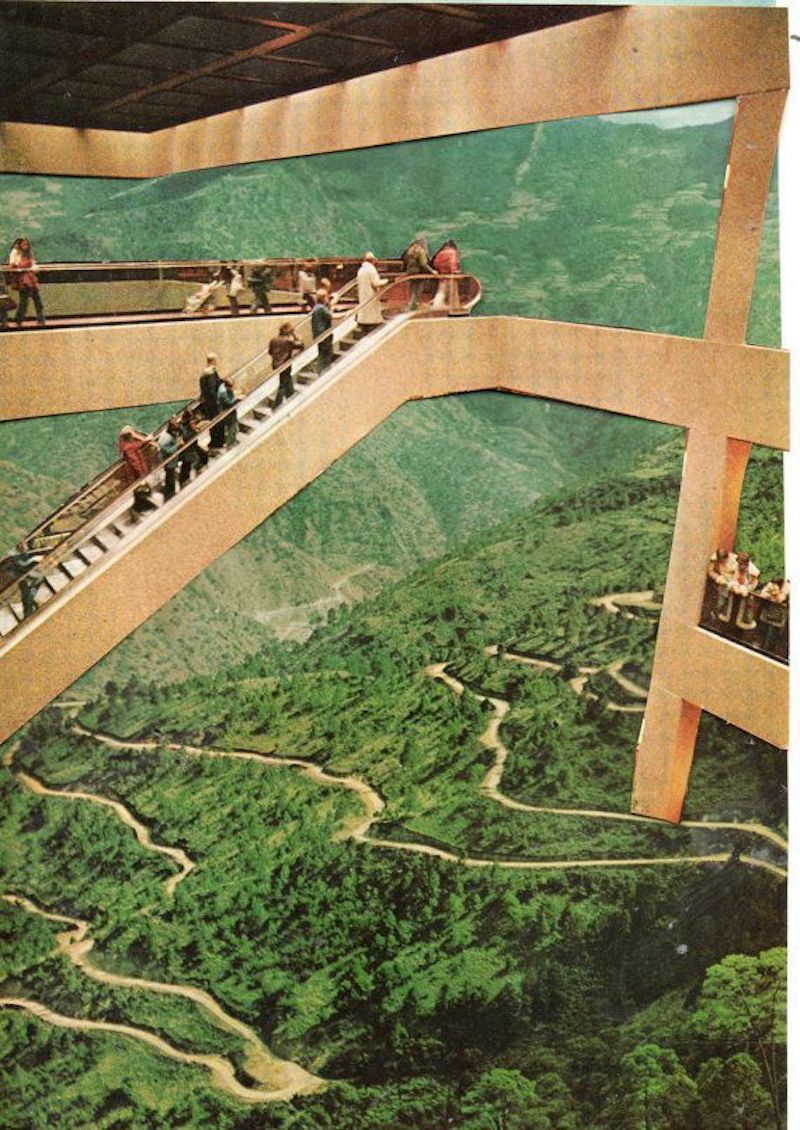

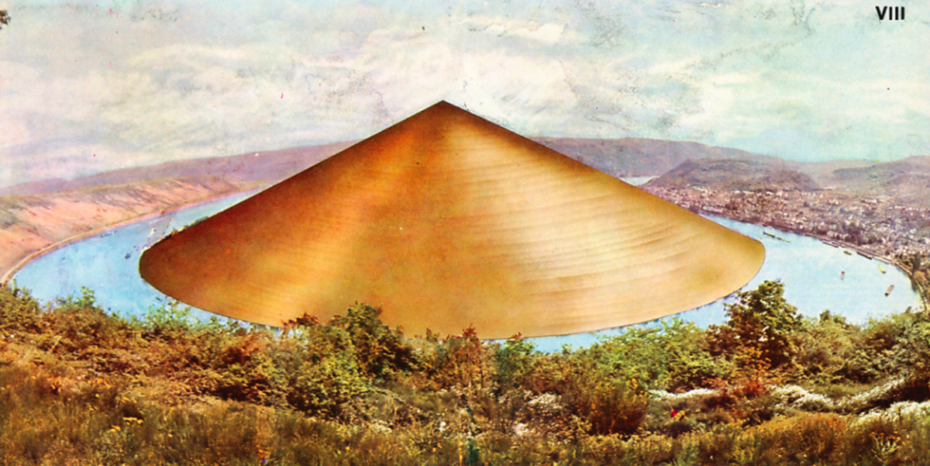

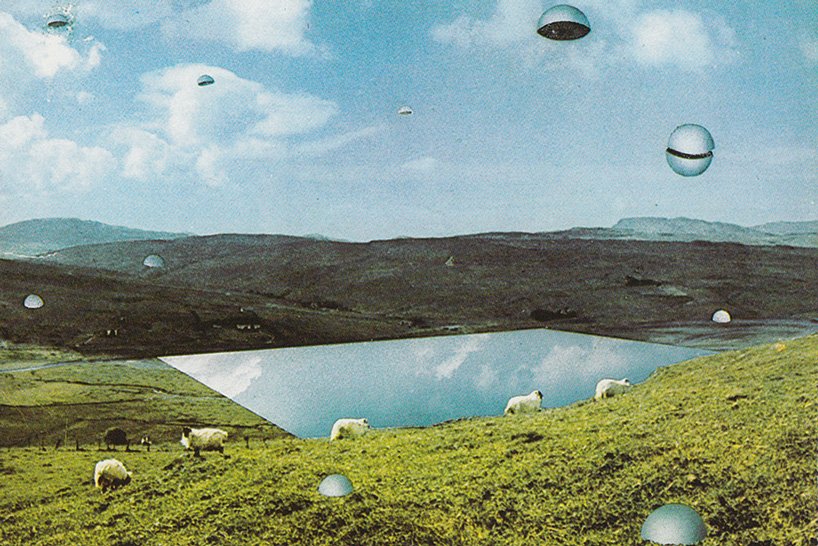

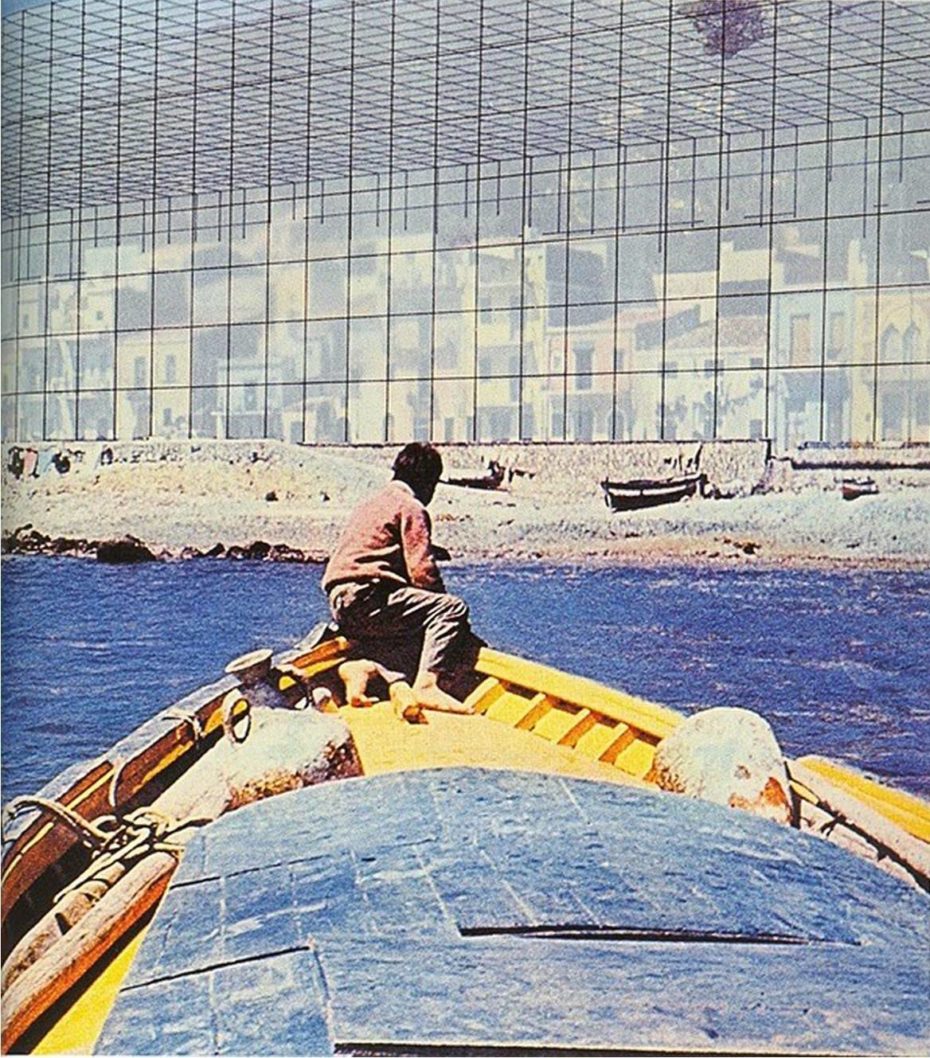

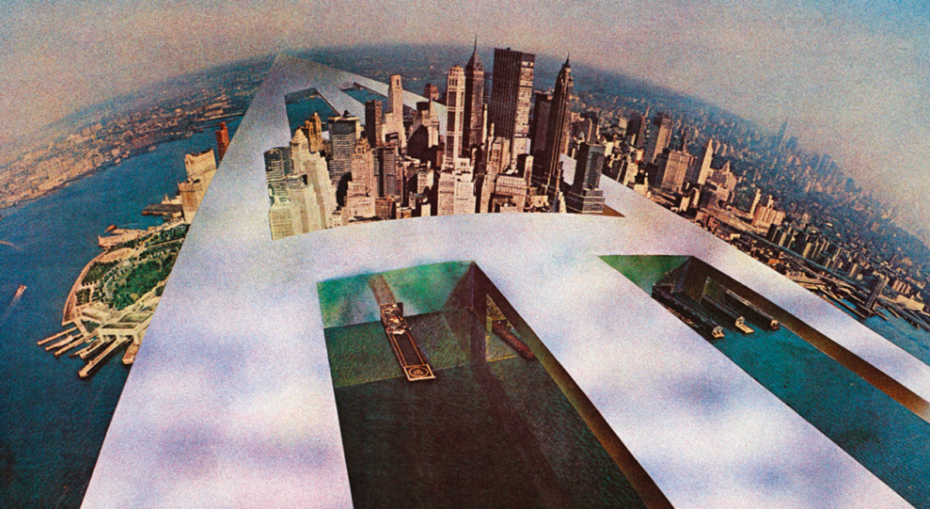

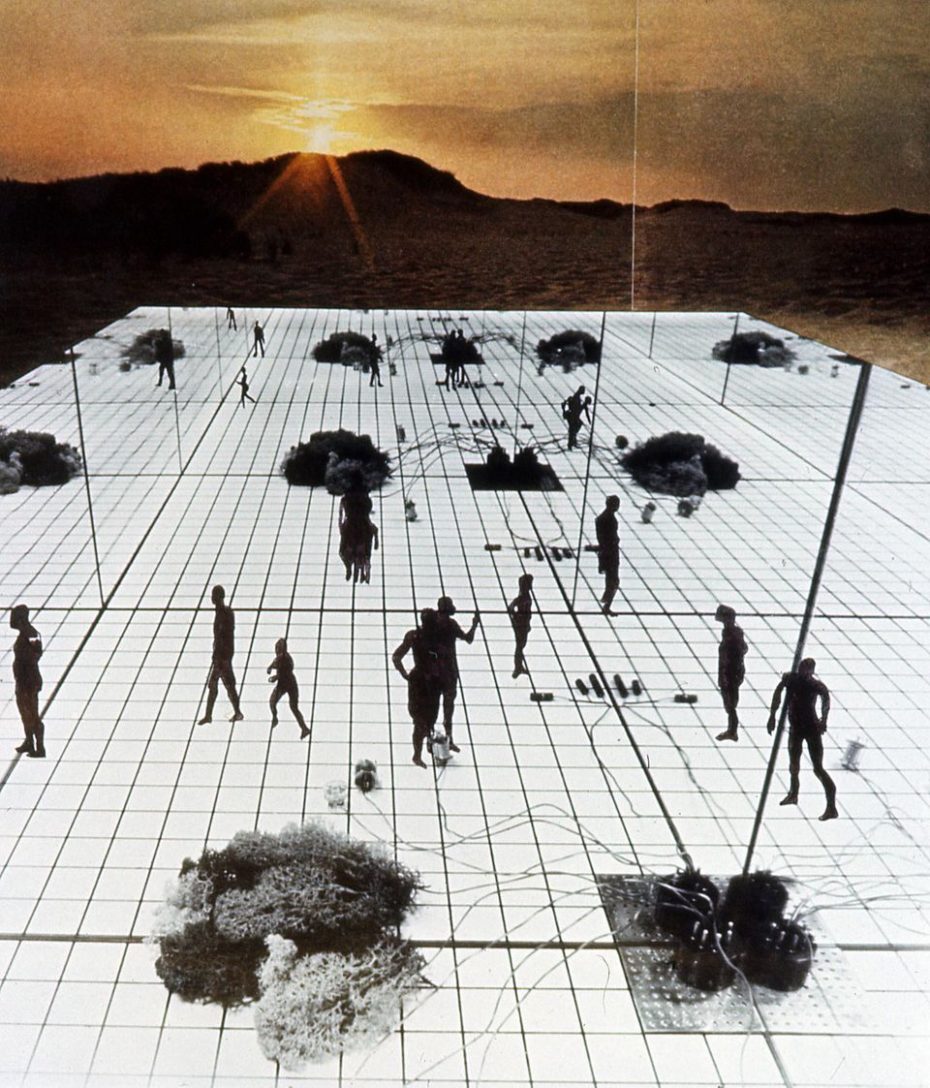

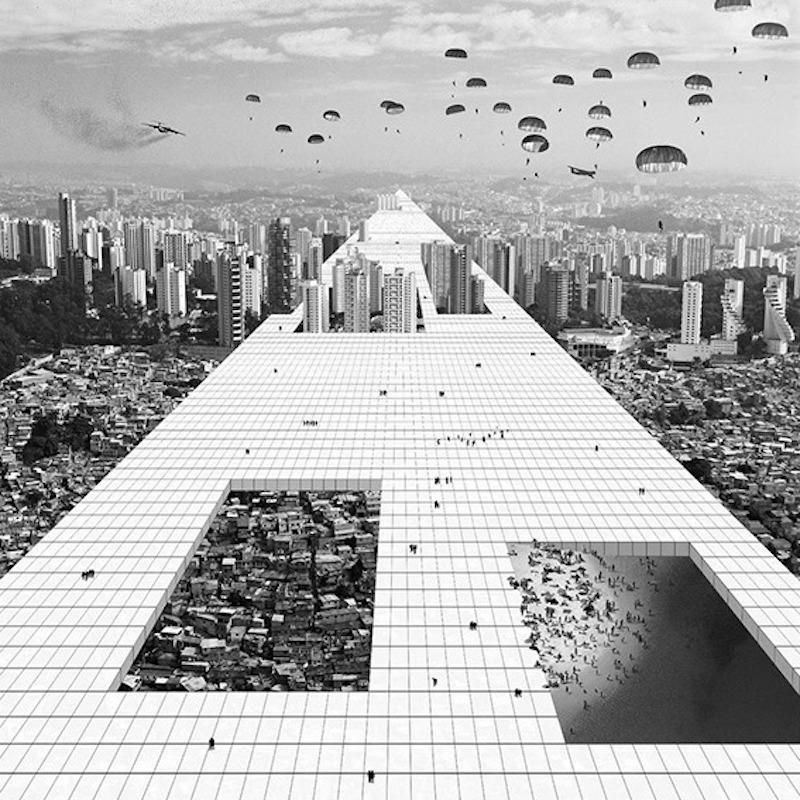

One of their most famous projects was the Continuous Monument: an Architectural Model for Total Urbanisation. Using founder Adolfo Natalili’s painterly background and the collective’s combined architectural studies, they produced forewarning snapshots of a world taken over by a giant, endless grid…

A dystopian vision, where the whole world became invaded by a monotonous, even monstrous structure that took over nature and reduced the world to nothingness, was Superstudio’s protest of globalisation that was overtaking the world. They were also critical of the increasing destruction of the eco-system at the time. It was a world with no individuality. Natalini described them as “images warning of the horrors architecture had in store with its scientific methods for perpetuating standard models worldwide.”

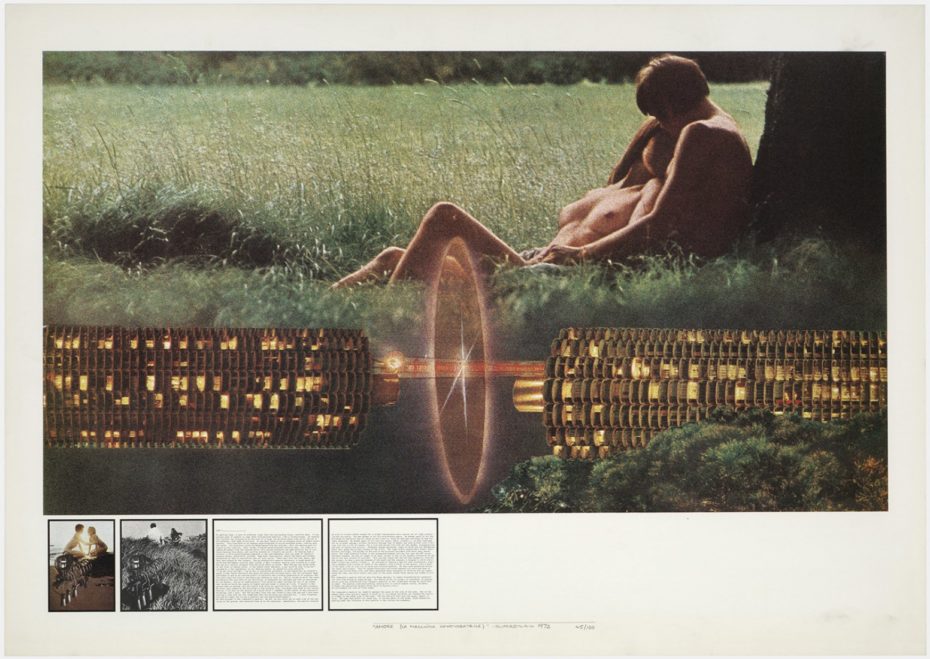

In an article for the New York Times, Stephen Wallis called their interconnected Supersurfaces, which were accessed by plugging in “eerily prophetic.” They anticipated the world wide web, the internet – words that are now perfectly fitting when describing their vision.

Nevertheless, some academics like Ross Elfine saw these dystopias in a positive light too. He wrote that this alternate universe could allow its inhabitants to be free from suffocating urbanised settings they reacted against and unfair hierarchies. It was where people could be taken back to a simpler time where we were close to nature. People could go wherever they wanted to, talk to whoever they wanted to and live without superfluous stuff. The Supersurfaces were a space for those detached from current society, like hippies, to live freely.

“Our idea for Supersurface was kind of a pre-vision of what became the Internet…we wanted to show that design and architecture could be philosophical, theoretical activities and provoke a new consciousness.”

di Francia

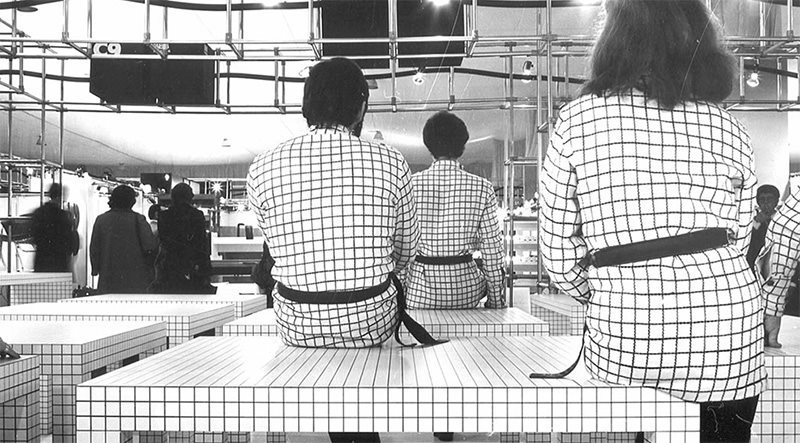

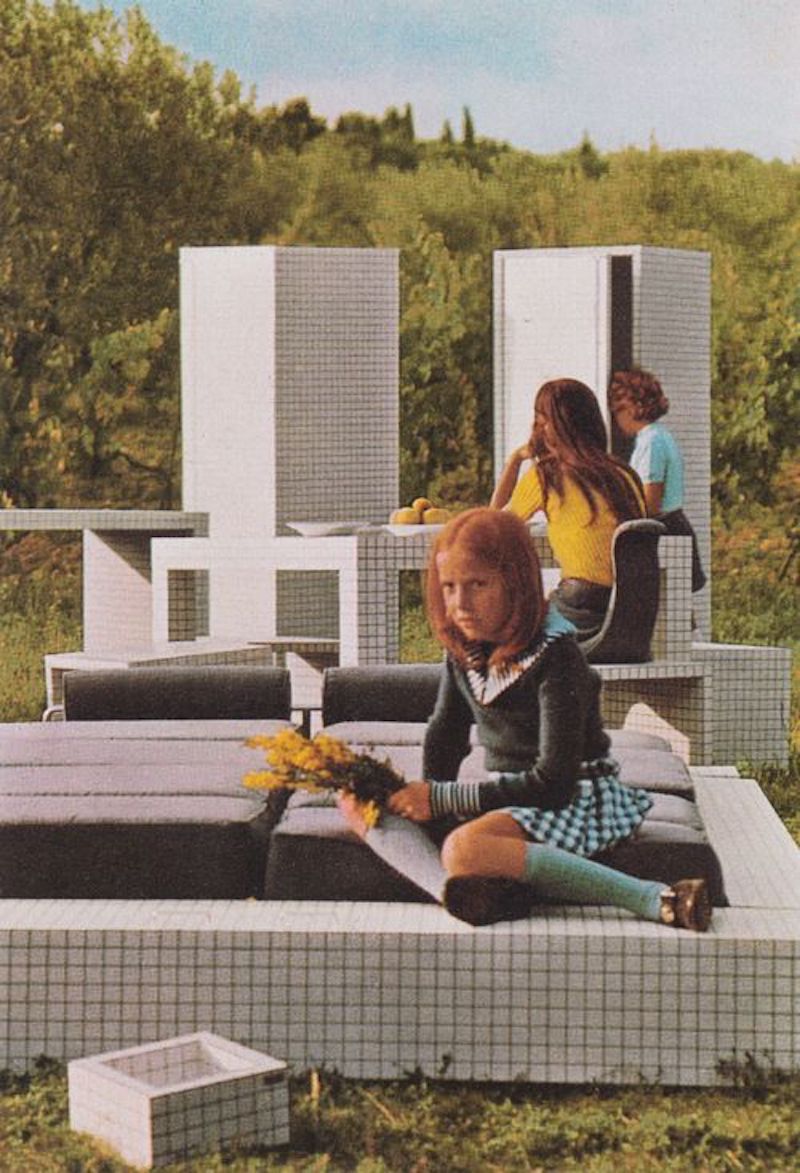

Inspired by their grid consumed worlds, they also created the Quaderna, a collection of minimalist furniture covered with plastic laminate, which is still in production today and sold by Zanotta:

In contrast to the collection for Zanotta, they also created some louder designs reacting to the blandness of Modernism. They were meant to be agitational, to attack the senses and to inspire their users into action, preceding the likes of the Memphis Group:

“Our problem is to go on producing objects, big brightly-coloured cumbersome useful and full of surprises, to live with them and play with them together and always find ourselves tripping over them till we get to the point of kicking them and throwing them out, or else sitting down on them or putting our coffee cups on them, but it will not in any way be possible to ignore them. They will exorcize our indifference.”

Superstudio

By 1978 the group amicably disbanded and went their own ways. Natalini passed away earlier this year in January 2020, predeceased by his co-conspirator, Toraldo di Francia in 2019. Although they never actually created any physical buildings, they embodied a revolutionary spirit and ambition that is almost tangible. They left an inspiring collection of visuals that is artistically impressive in itself; a reminder that even if your goals seem unattainable, you can always start somewhere. You never know what you’ll discover, or create, along the way.

Images courtesy of the Maxxi Museum.