Ah, Paris! Global capital of couture, style, and…menus? As café terraces welcome back patrons post-lockdown, it’s comes to the attention of our Paris team that tangible menus have gone digital across the city. Restaurants are displaying QR barcodes for customers to scan and access menus via their smartphones in order to avoid spreading les microbes. Now, we appreciate that electronic menus are an environmentally conscious option and most importantly in light of Covid-19 – hygienic. But there’s a special place in our hearts for those good old cartes du jour, and the big, laminated “fold-outs” from our favourite vintage diners and iconic cafés. So we’re wondering, could this mean the end of the restaurant menu forever? The question prompted us to take a little walk down memory lane with the underrated art (and history) of the restaurant menu…

For starters (see what we did there?), the earliest human menus were found in Pompeii, scrawled on a wall of a thermopolium, essentially the equivalent of a modern fast-food joint:

Serving primarily the lower classes, meat was not often part of the menu here, but mostly soups. Wealthy Romans had a pretty eclectic diet however, eating fruit, shellfish, and even giraffe. In 2014, archaeologists found one’s butchered leg by an ancient restaurant. But we digress.

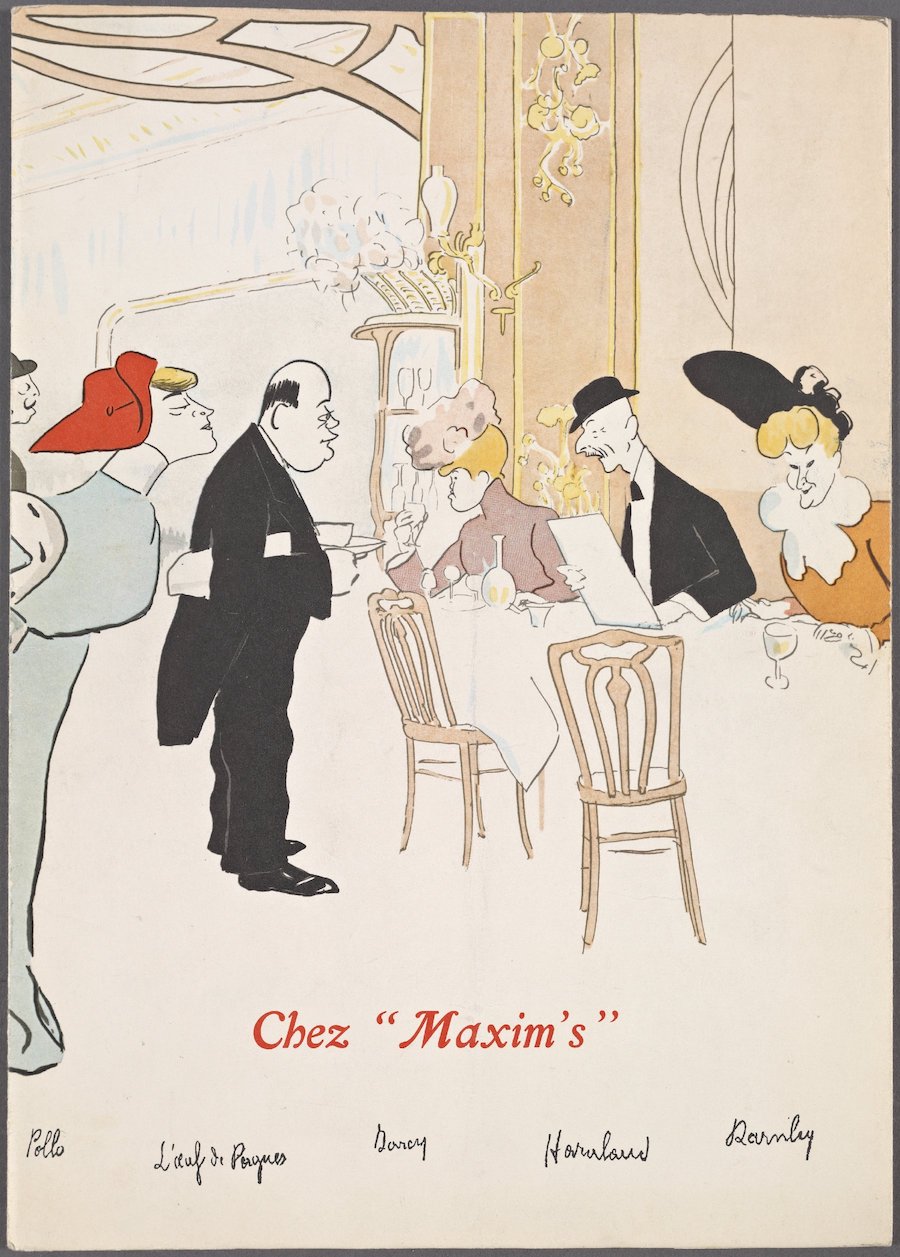

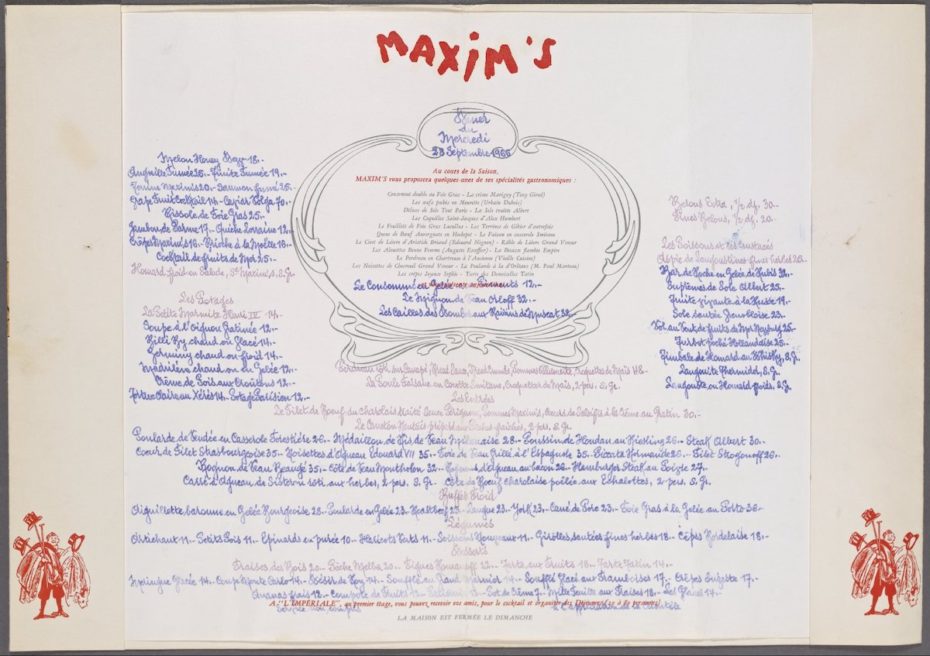

The modern, written menu as we know it popped up in France in the 18th century – Parisians love their gastronomie. Here’s a lovely vintage menu of Maxim’s, a Right Bank institution:

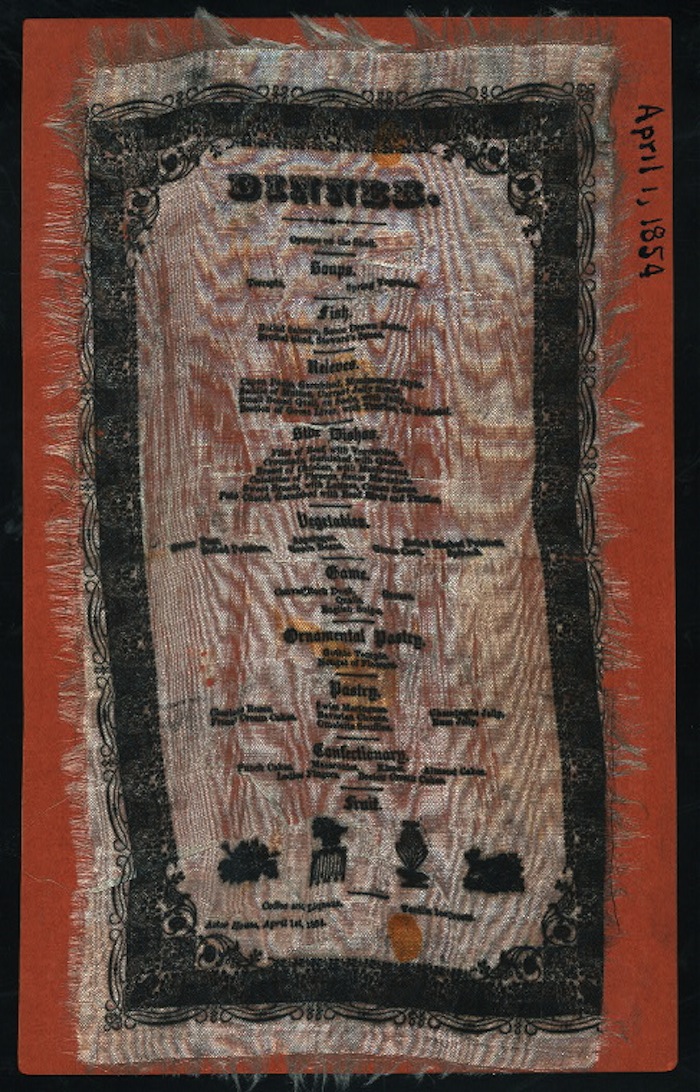

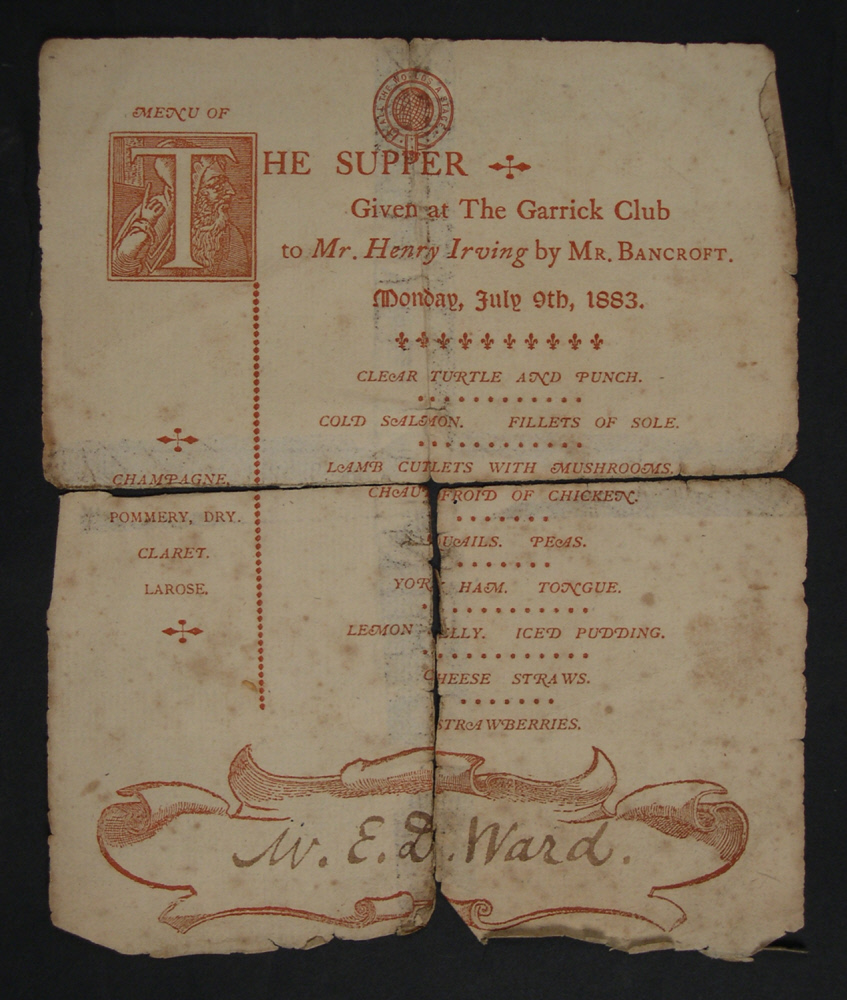

By the 19th century, they had made it to America. Check out the cloth menu for New York City’s Astor House, or the menu serving “Clear Turtle and Punch” from the party of one Sir Henry Irving…

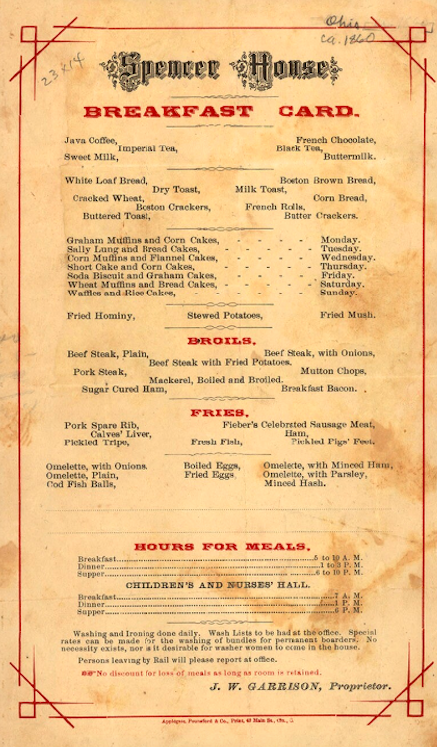

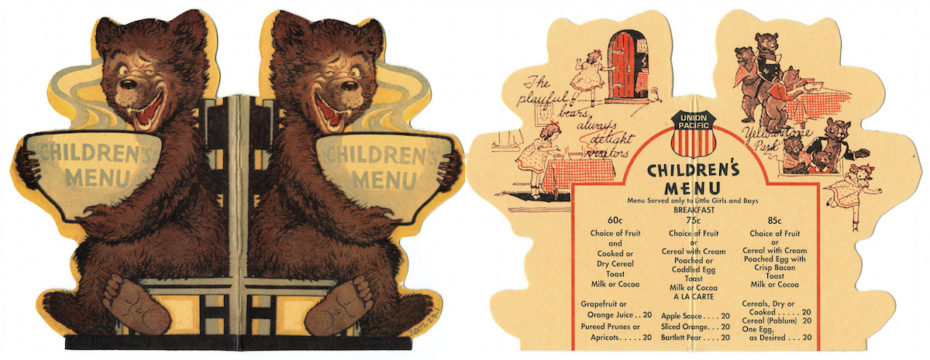

The Spencer House menu (1860s) below offered a different meal each day of the week; Monday was a breakfast of “Graham Muffins and Corn Cakes” while Tuesday was “Sally Lung and Bread Cakes.” They also had a “Childrens and Nurses Hall.” What a time.

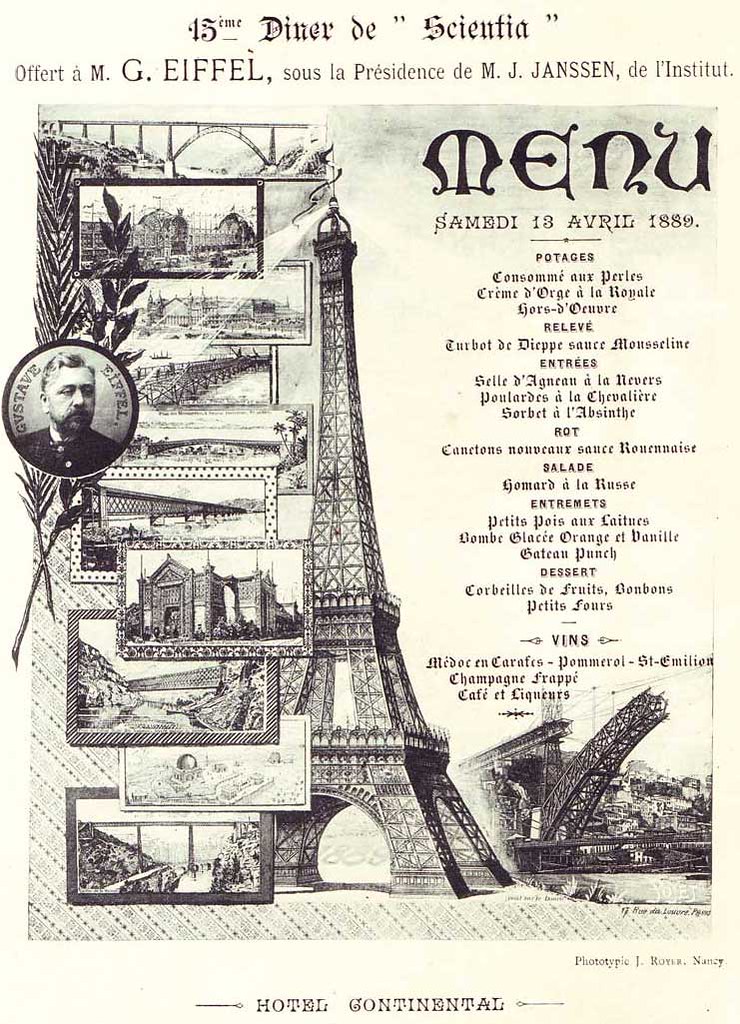

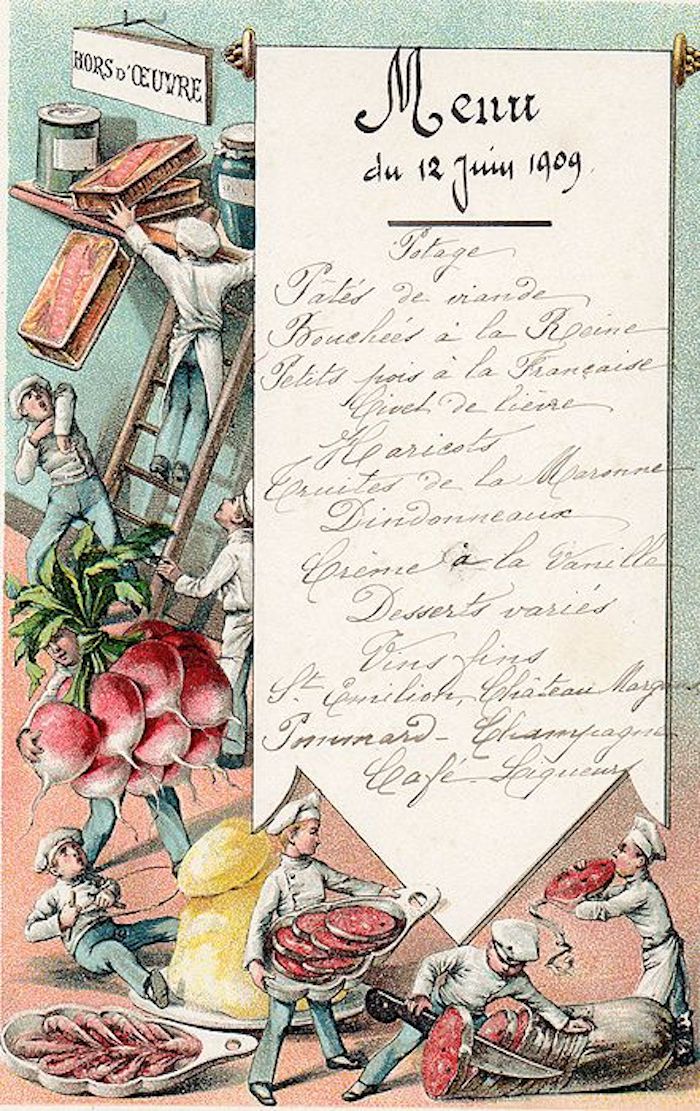

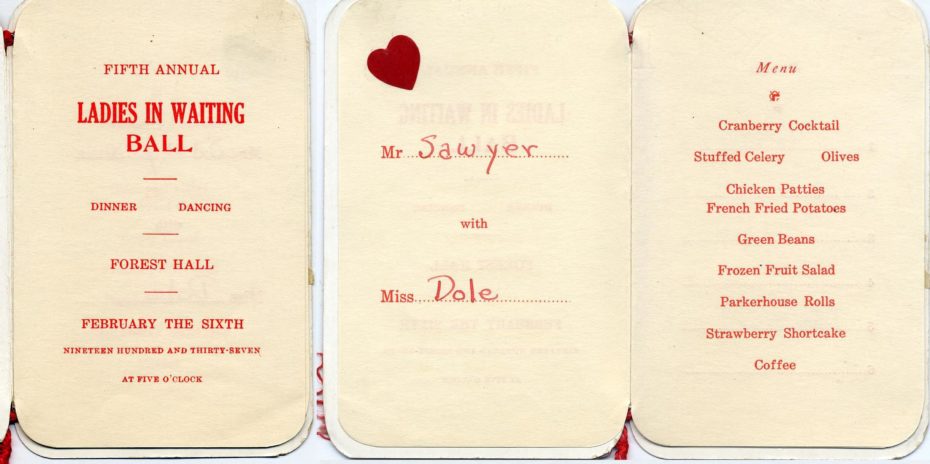

Menus actually got their start in special occasion events like weddings, graduations, or various anniversaries. They were costly and time-consuming to make, so it was only the fanciest restaurants that had the luxury of offering its patrons menus in the early days…

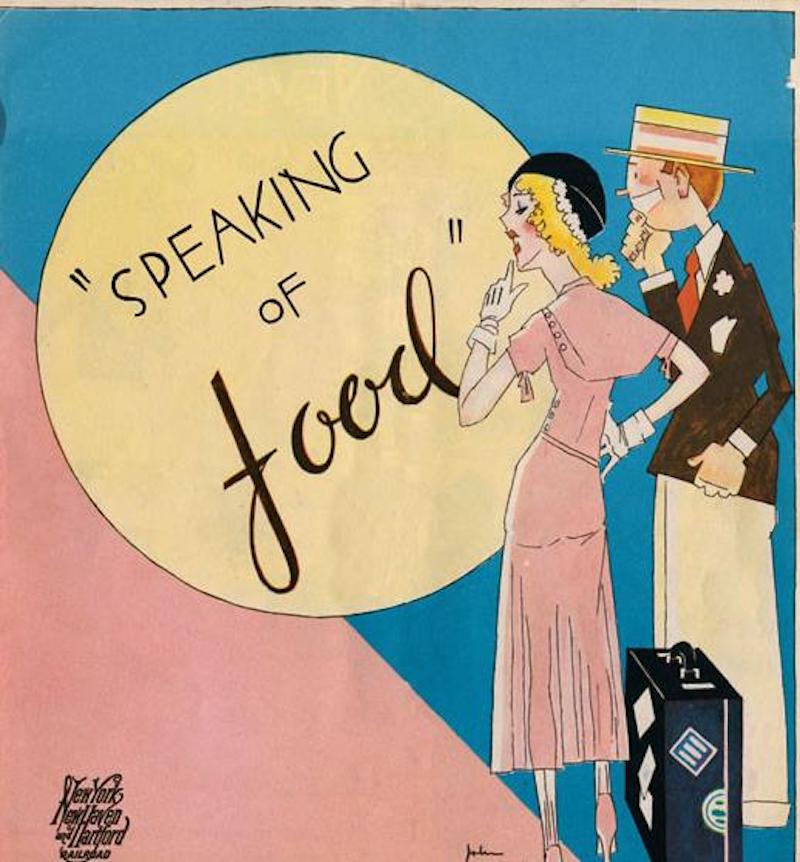

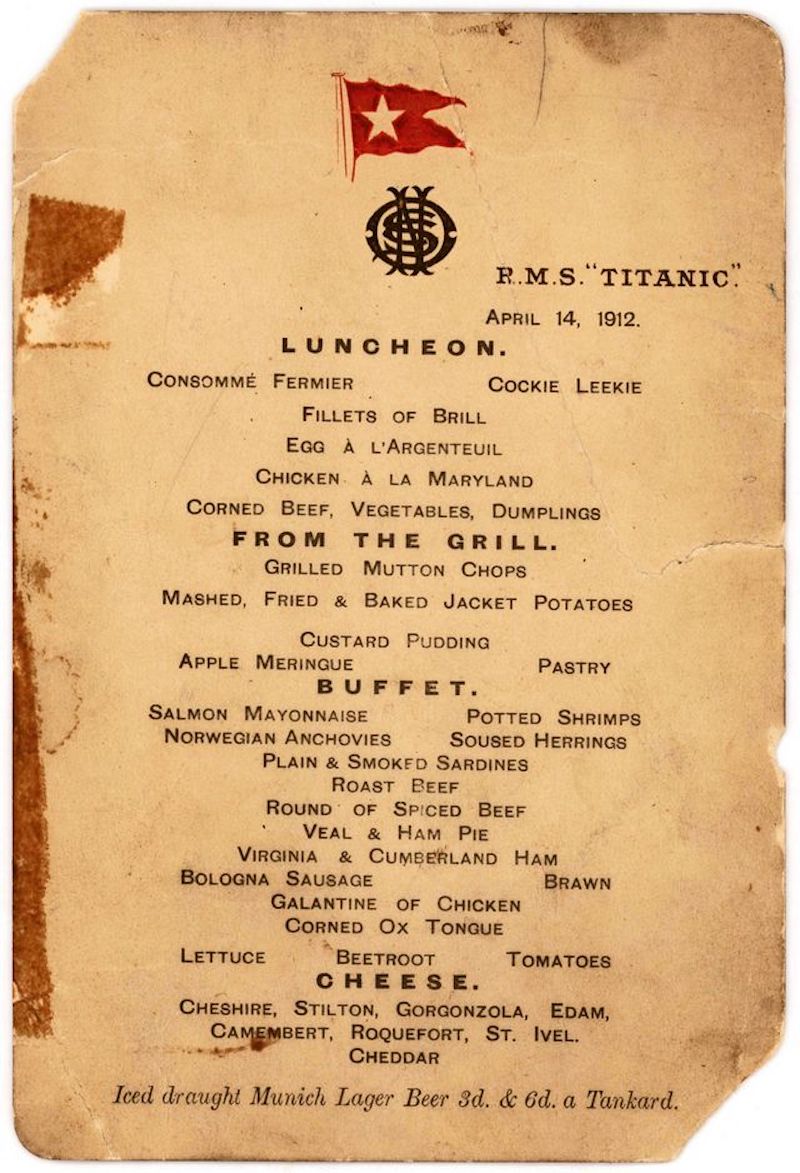

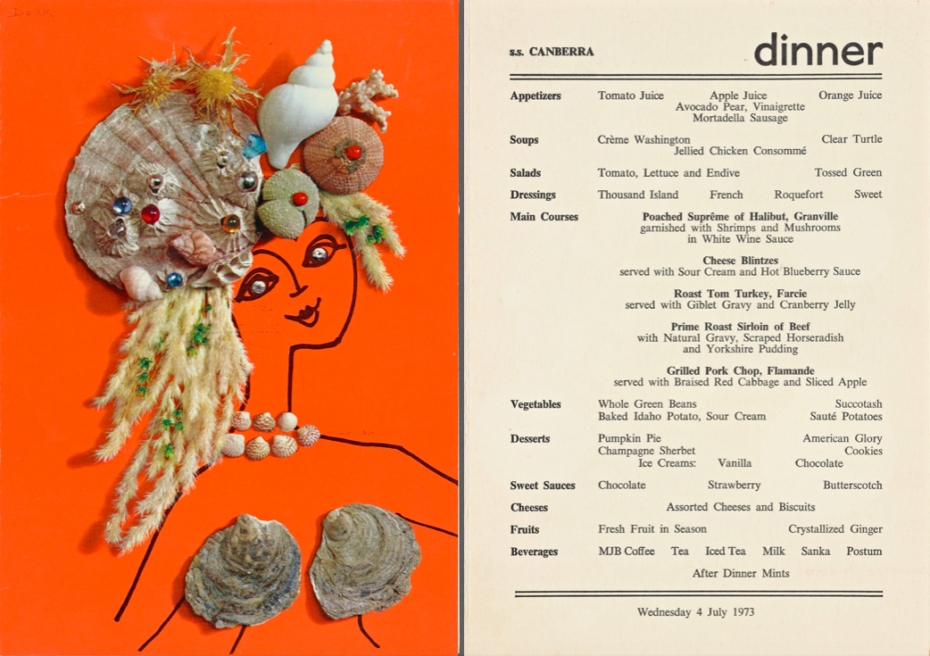

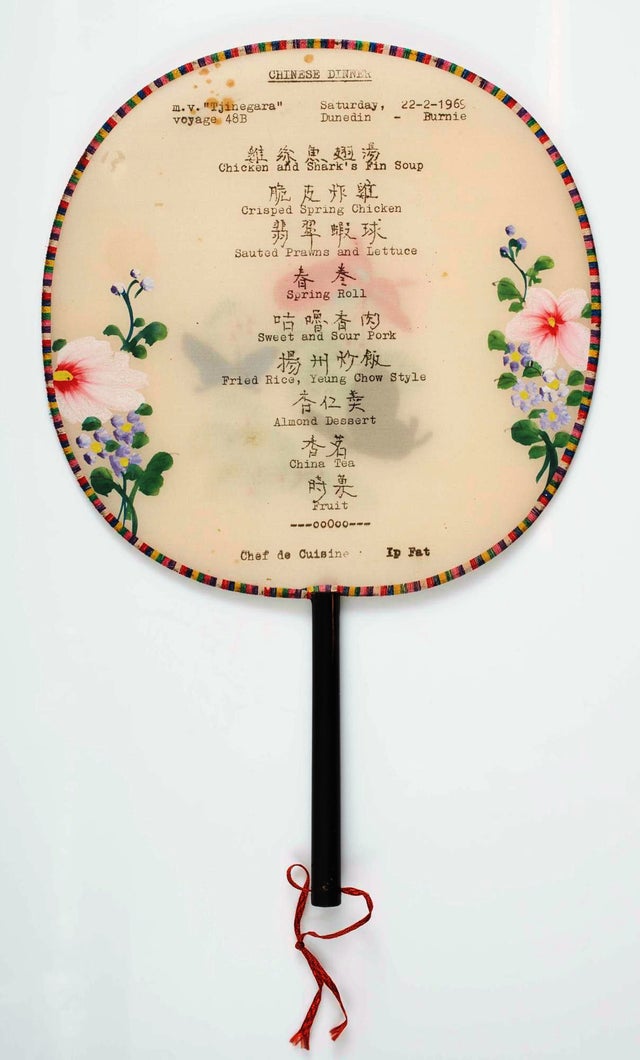

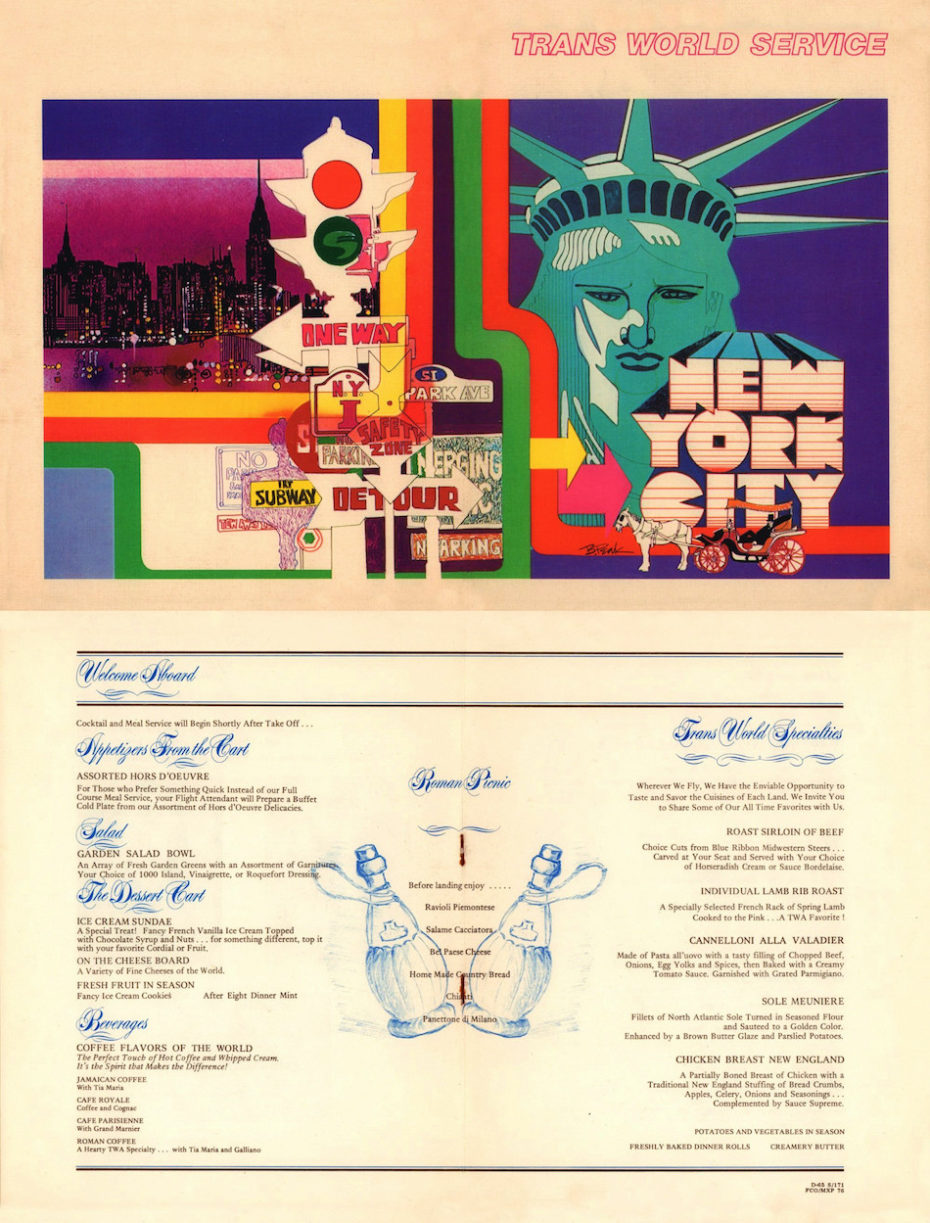

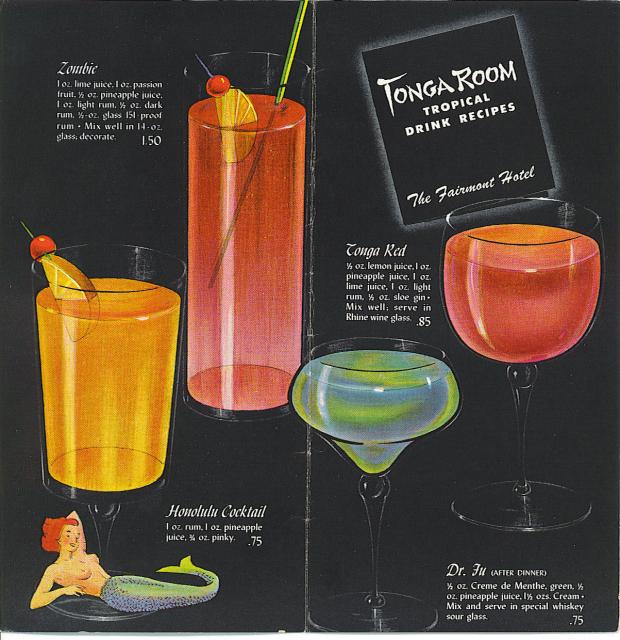

Some of the most beautiful 19th and 20th century menus recall times when travel was also considered quite grand. Taking the train? Hopping on an ocean liner, flying in a plane? These weren’t just a means of travel, but an event in themselves. Menus reflected that. Take a look at the last lunch menu from the ill-fated Titanic:

Anyone ever tried Corned Ox Tongue? The menu was put up for auction in 2015 and an anonymous buyer shelled out a whopping $88,000 for the souvenir.

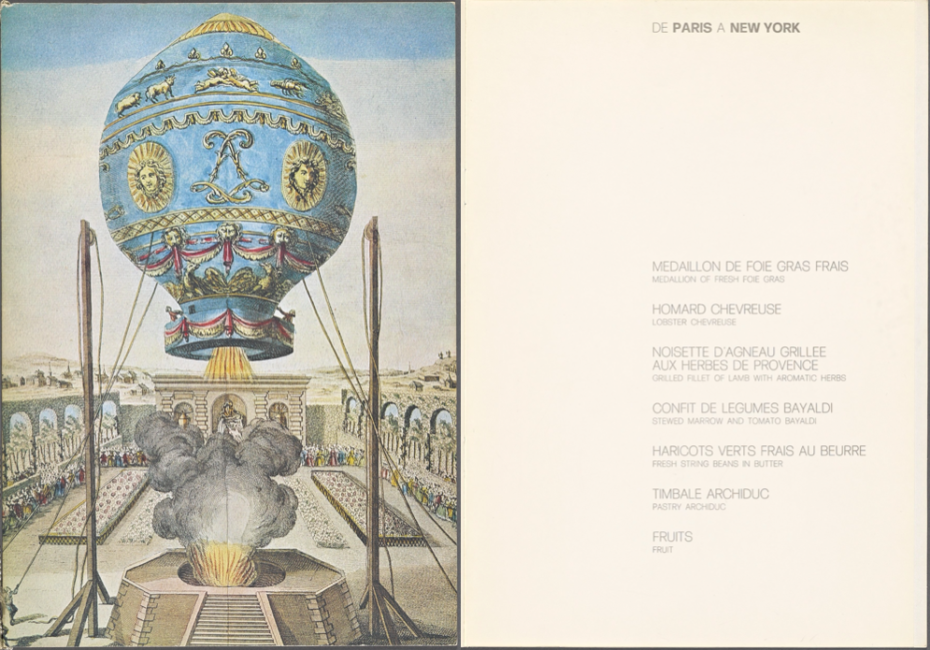

The menu for the fleet of doomed Concorde planes was suitably grand, prefacing it’s selection of foie gras and lobster with a history of the hot air balloon.

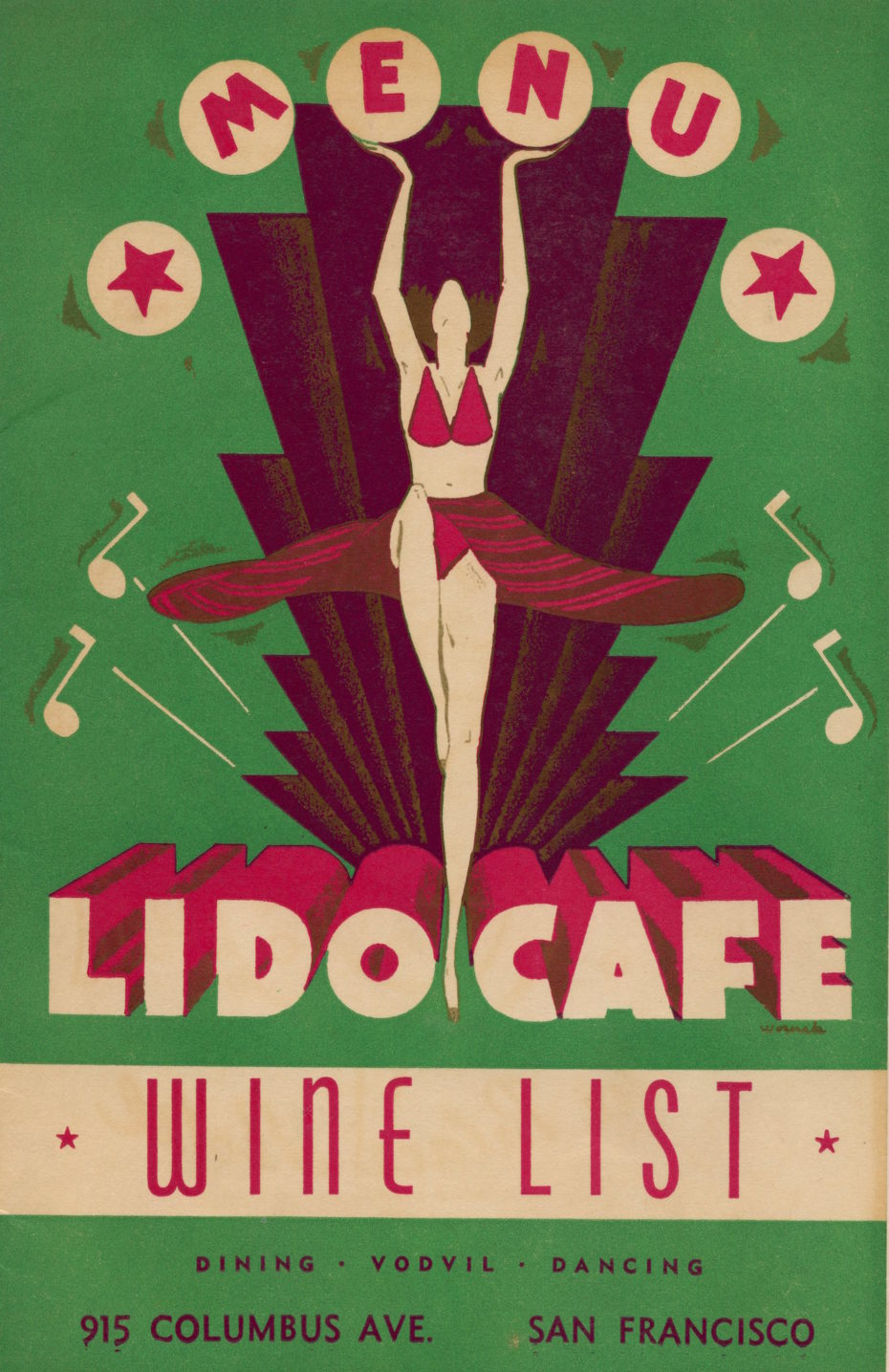

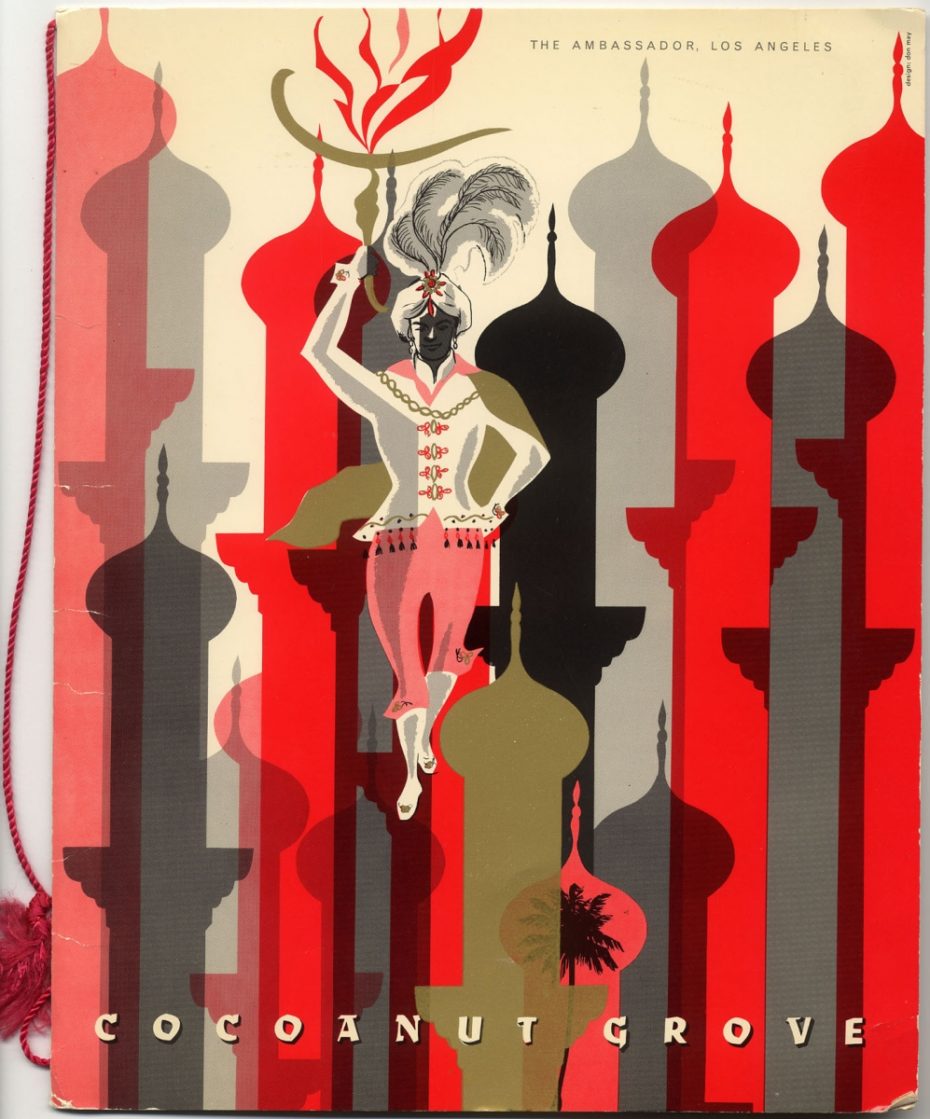

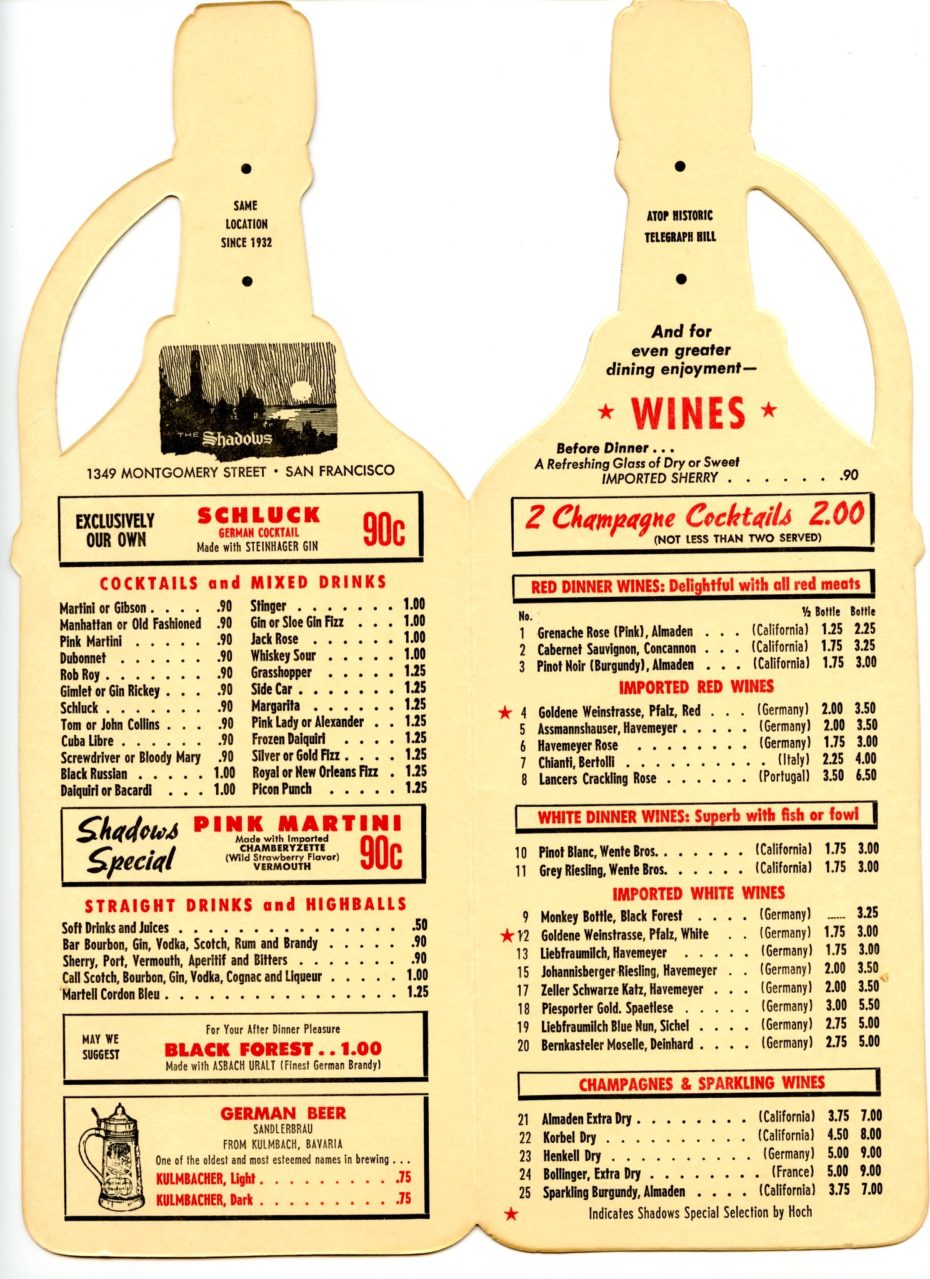

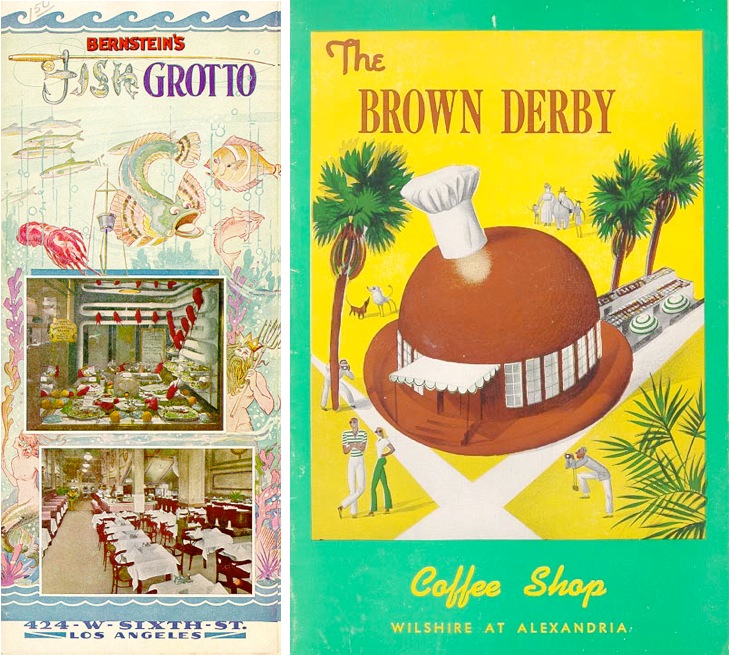

Before the internet, when you couldn’t Yelp your restaurant or check social media posts to gauge the atmosphere, menus posted outside had a big responsibility in giving customers an idea of what to expect. You were presented a choice of culinary delights, as well as a sense of fantasy and escape through the artwork…

The secret psychology behind menu making is pretty interesting too. In the 2019 podcast “Menu Mind Control,” Alison Pearlman, author of a book on menus called May We Suggest: Restaurant Menus and the Art of Persuasion (2018), dives into the clever little ways menus have been telling us what we’re hungry for all along…

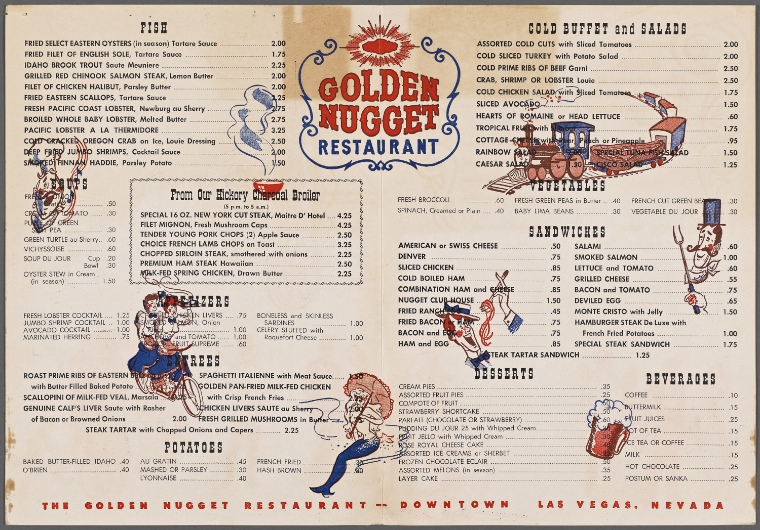

When prices aren’t listed, for example, it’s usually because you’re at a more expensive restaurant, or the owners don’t want price to deter you from falling in love with a dish. Pearlman also says most restaurateurs know it’s not a good idea to organise your menu from high-to-low in price, economically. Folks tend to spend more when it’s a mixed bag.

Another trick: have one item that’s markedly more expensive than the rest, to make the customer feel like they’re getting a deal. That’s called an “anchor price.” It’s quite sneaky, and potentially wasteful if no one is actually ordering your $36 lobster roll.

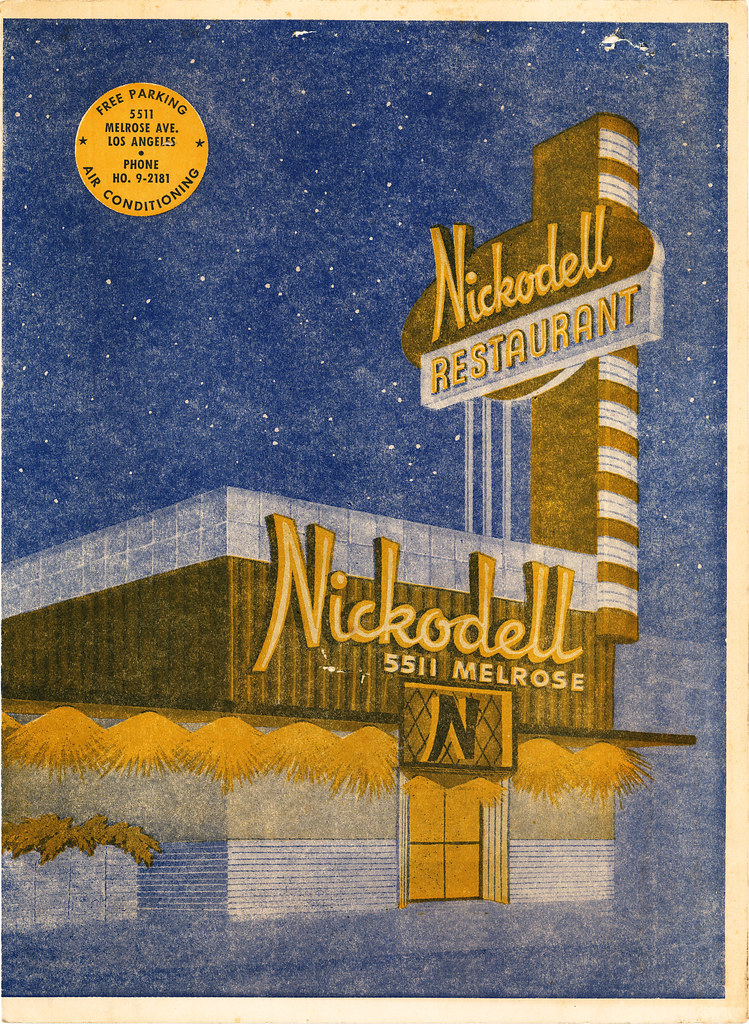

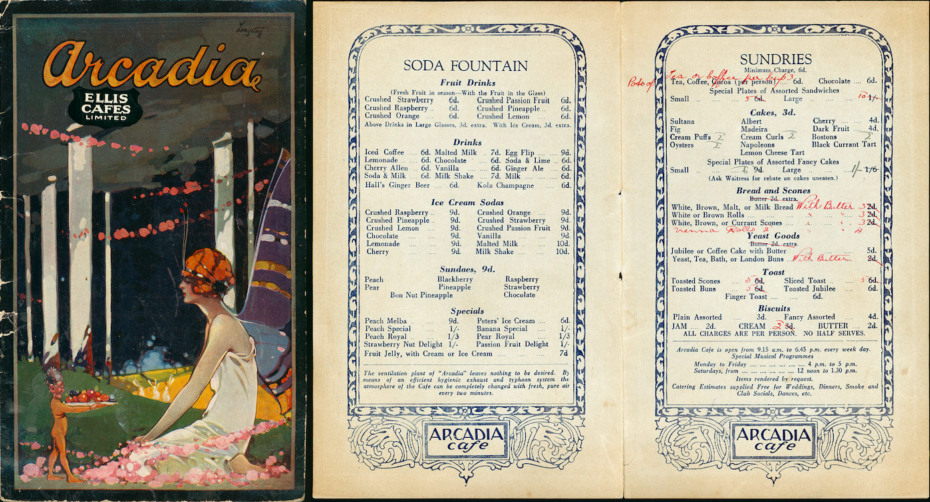

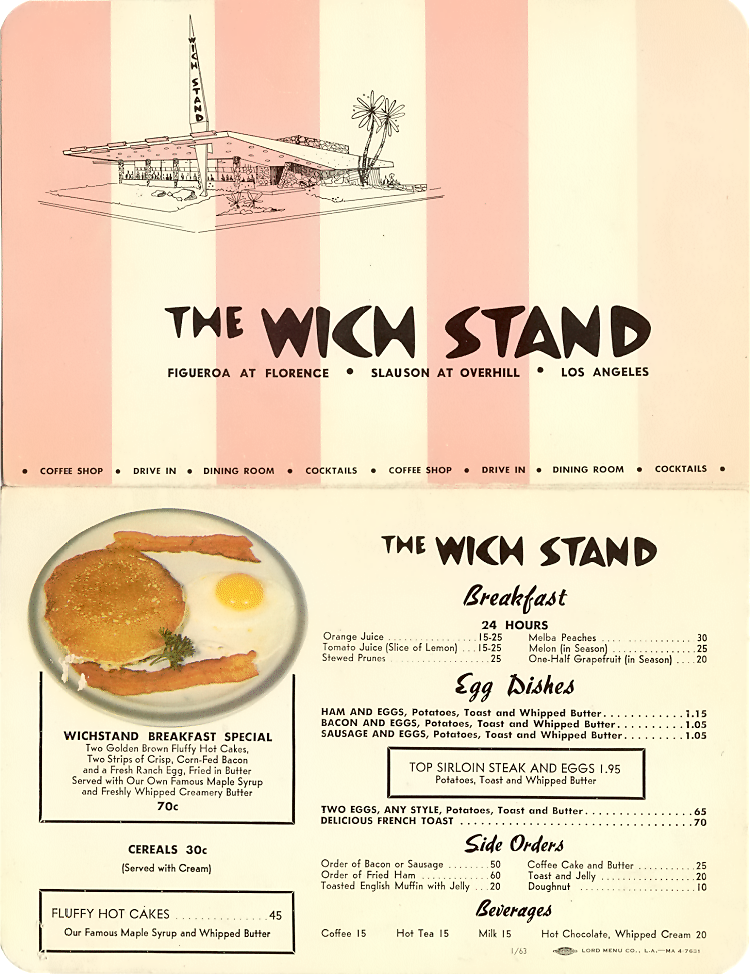

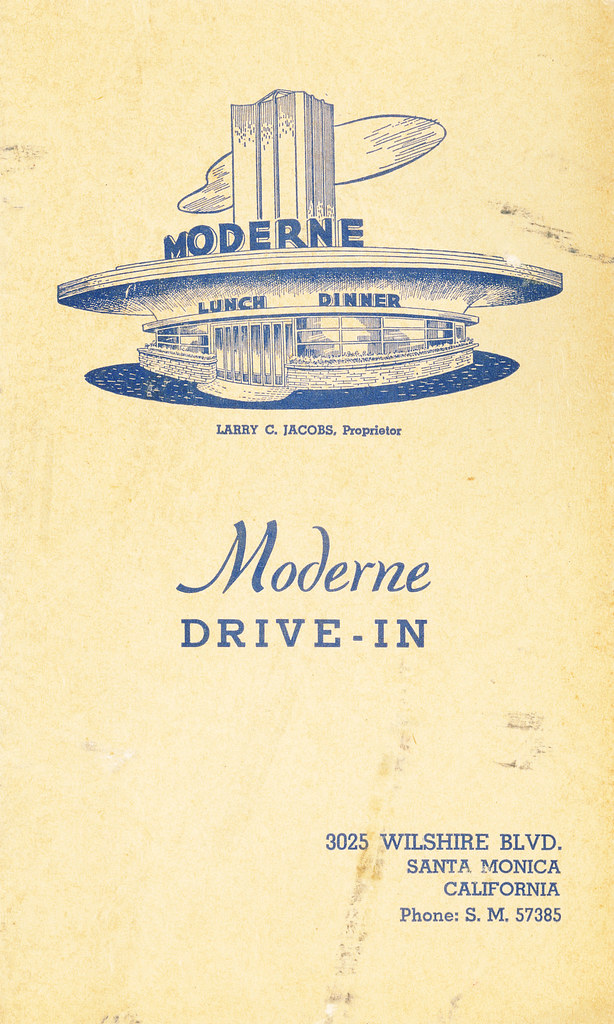

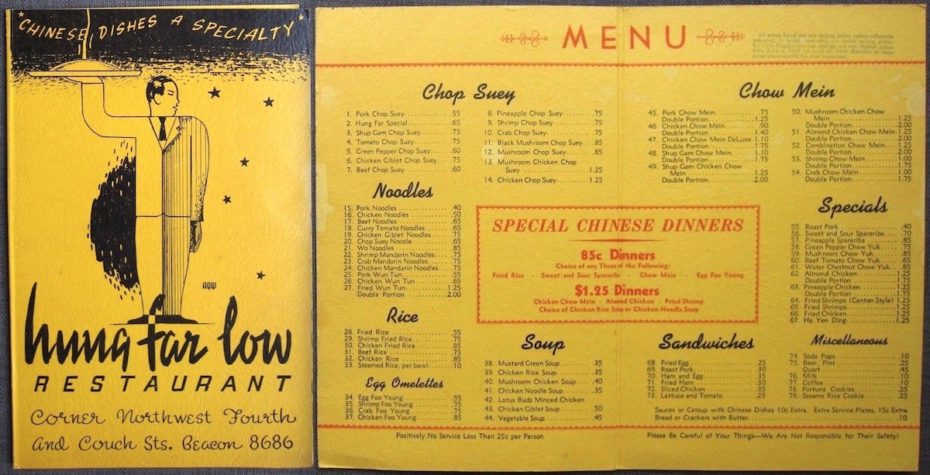

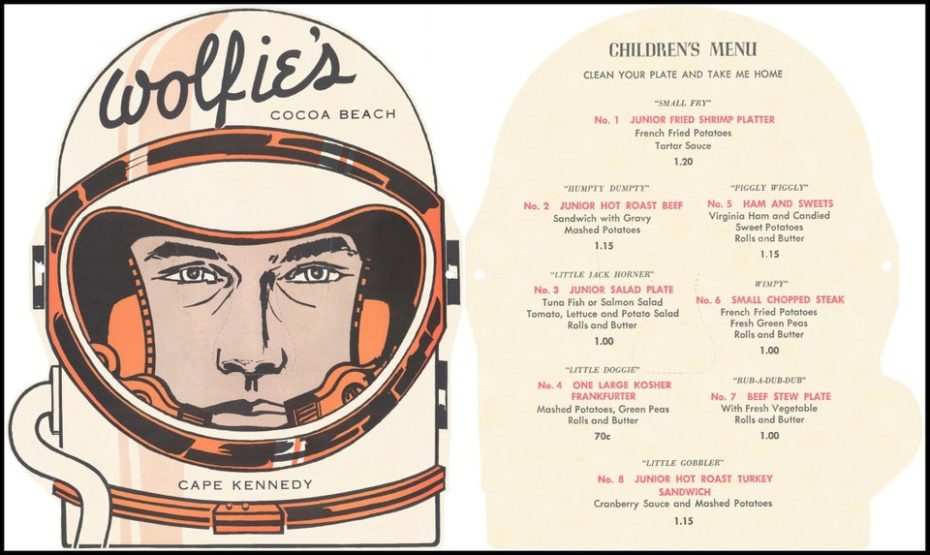

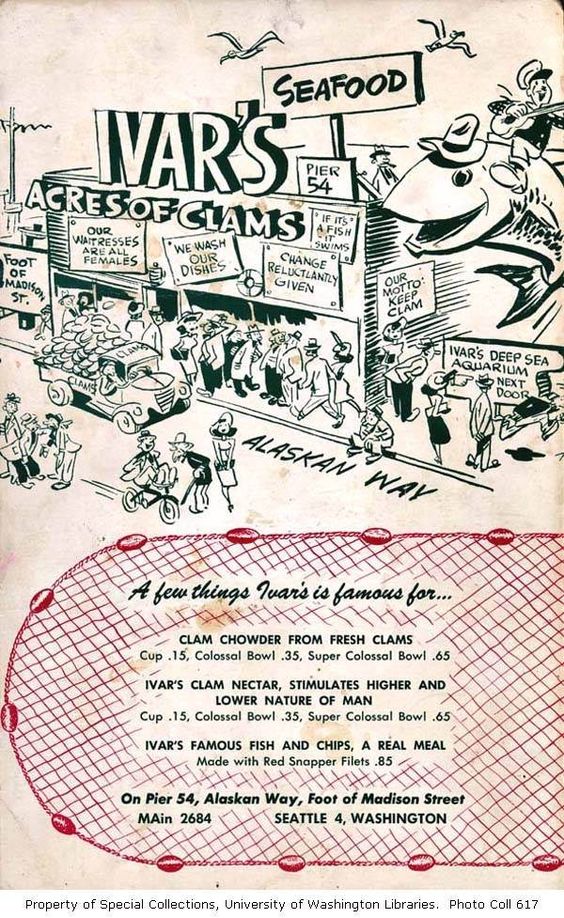

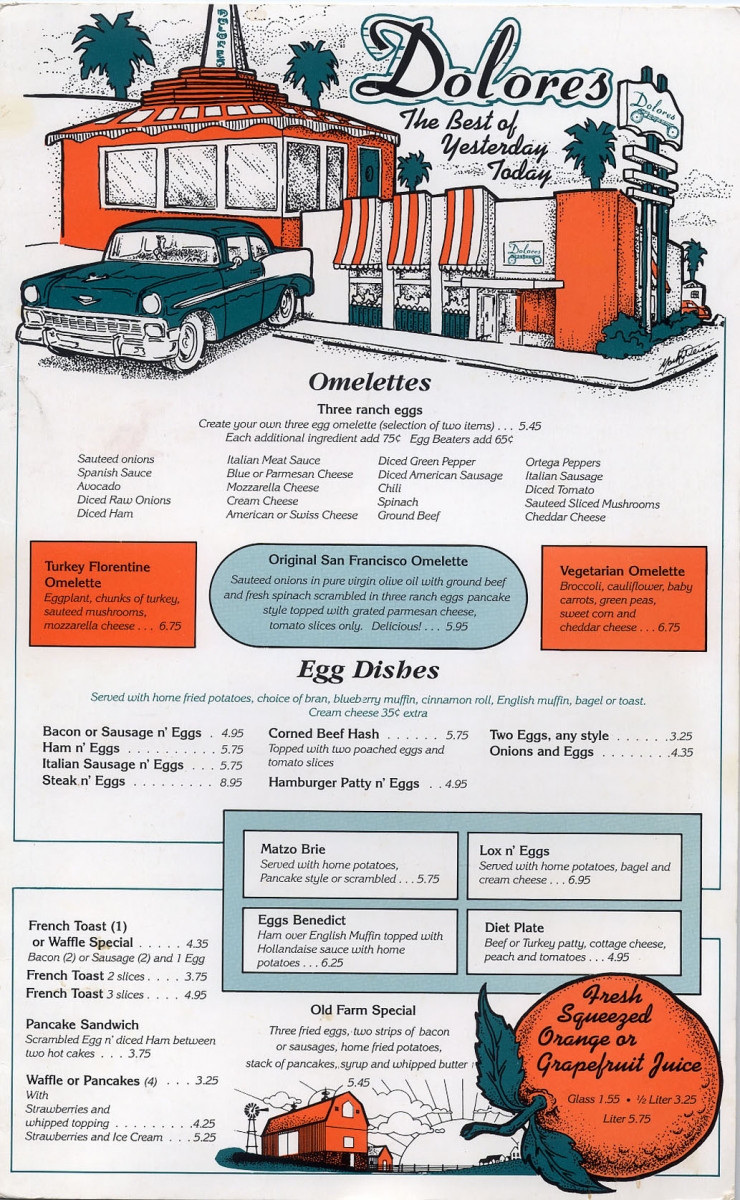

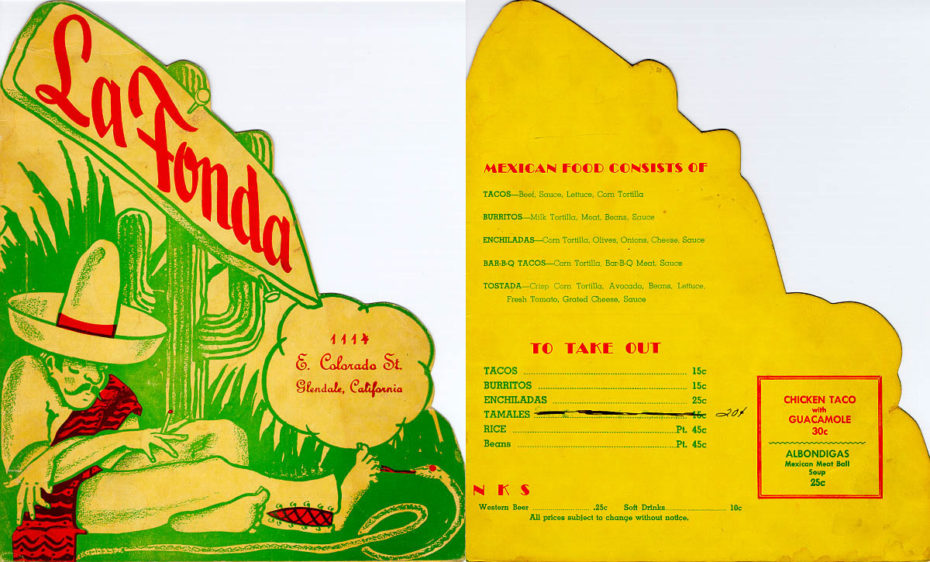

When novelty roadside restaurants and drive-ins began to thrive, especially in Midcentury America, menus exploded with just as much kitsch energy in both their forms and descriptions. While there were accuracy laws in place about how much a restaurant could embellish its food descriptions, it feels like the 20th century was a time when menus were most creative…

Los Angeles in particular has such a rich history in Pan-Latino cuisine. While the dreamy menus of Glendale’s “La Fonda” are no more, consider ordering from similarly old school LA institutions like El Cholo, est. 1923. Not only is it the oldest operating Spanish-Mexican joint in LA, but it has been donating proceeds to Black Lives Matter. Order up!

La Fonda’s menu feels relatively simple compared to the other end of the 1950s dining spectrum – the one with descriptions that were a mouth full in and of themselves, due to “The Restaurant Associates,” a new organisation that encouraged wordy listings. That tradition seeped into TV adverts as well, and lives on to this day. Perhaps most famously, in the viral “baked in a butterfly, flaky crust” spot. A true classic:

In the biz, they call this “over-adjectiving.” In fact, you ever notice how random French words like “chiffonade” and “gratin” will also pop up randomly on menus? That, again, is a way to harken back to the exalted gastronomic history of Paris. Insiders call it, “menu French.” Sometimes, it feels a little overwhelming.

Fascinating to see how things have and haven’t changed. American millennials, for example, will be surprised to see that the drugstore Walgreens actually served “liver sausage sandwiches” back in the day.

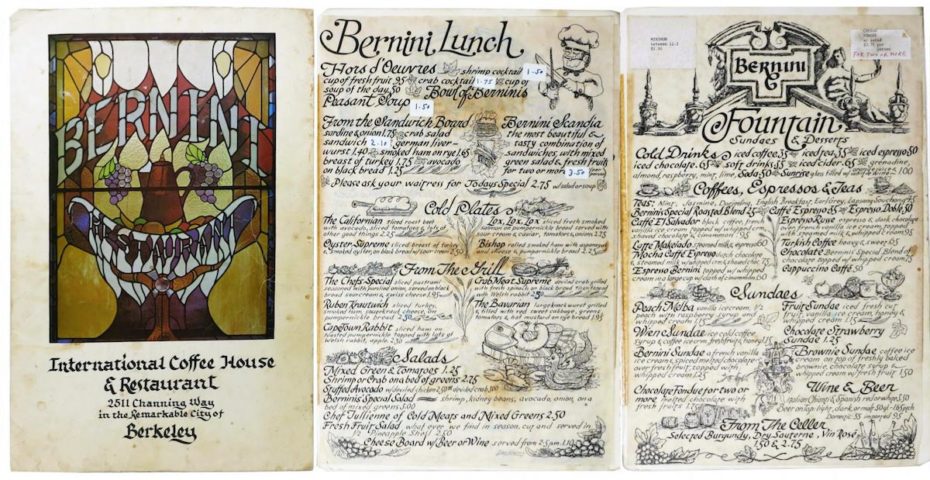

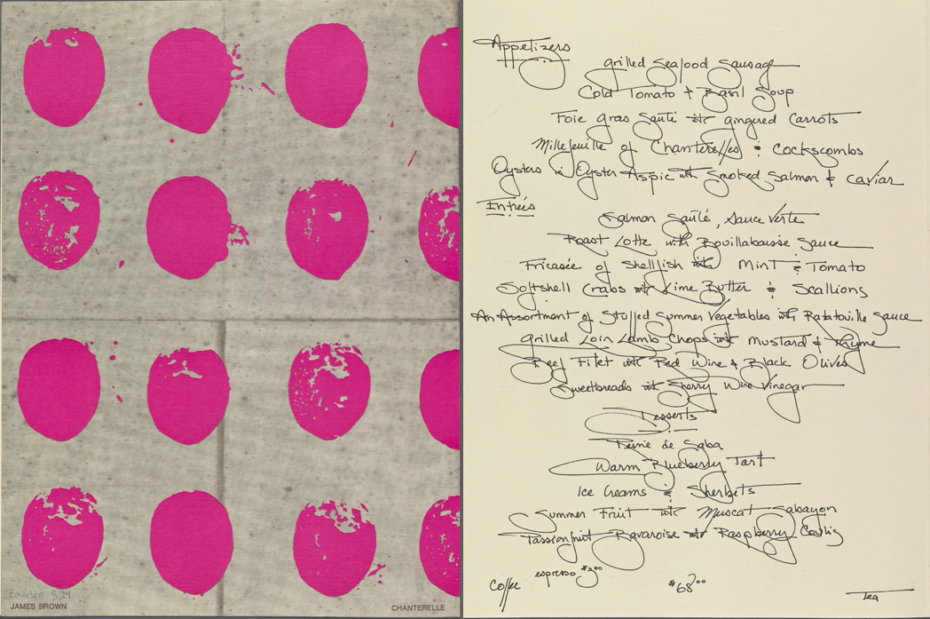

Menus went for the Wow Factor in different ways, representative of their target clientele. Consider the beloved and bygone New York restaurant, Chanterelle, est. 1979 in SoHo (sadly shuttered in 2009). It was known for commissioning cultural icons like Keith Haring, Cindy Sherman, Allen Ginsberg, and even James Brown to design their menus. Check out his design below:

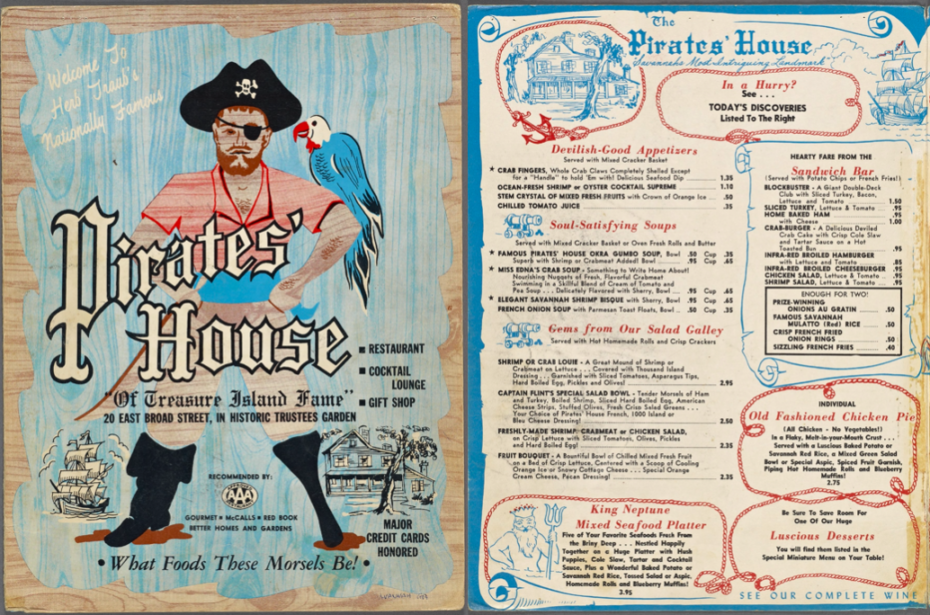

We’re also suckers for some cheesy copy, for which Pirate-themed joints are a treasure trove. “What Foods These Morsels Be!” Love it.

Also gotta love an aggressive steak:

There’s just so much for people to love about menus. In fact, the New York Public Library has an incredible collection of 25,000 menus dating back to the early 19th century, all collected by a woman named Miss Frank E. Buttholph (1850-1924). The Library describes her as “somewhat mysterious and passionate figure.” She donated her collection to NYPL on her deathbed, and we’ve featured more of them in this article.

Will Covid-19 be the downfall of tangible menus? Only time will tell. But rest assured: while we may miss them, digital menus can be really helpful in your favourite burger joint’s understanding of what people are ordering thanks to the screen data it gathers. Other forms of analogue menus continue to endure; the chalkboard menu tradition is alive and well in Europe, and perhaps to a lesser extent America, and the Japanese tradition of seeing realistic 3-D models of your food is very popular, and was pioneered in the 1920s by candle makers. Today, they’re made with a material call polyvinyl chloride, the closest thing we have to the eternal elixir of life. These babies don’t crumble.

We’re optimistic about the future of menus in dining. Life, as they say – and creativity – finds a way. What do you think?