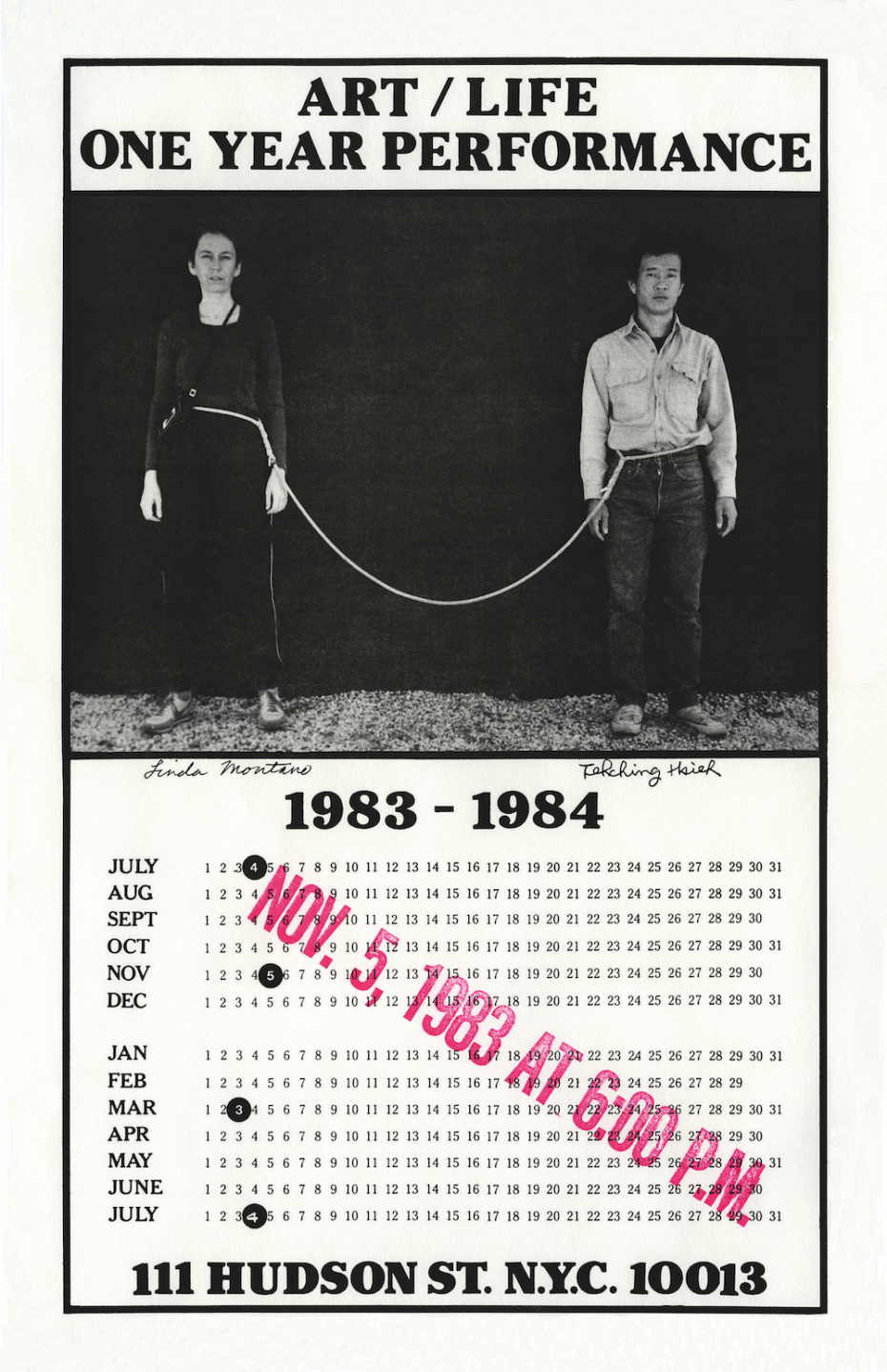

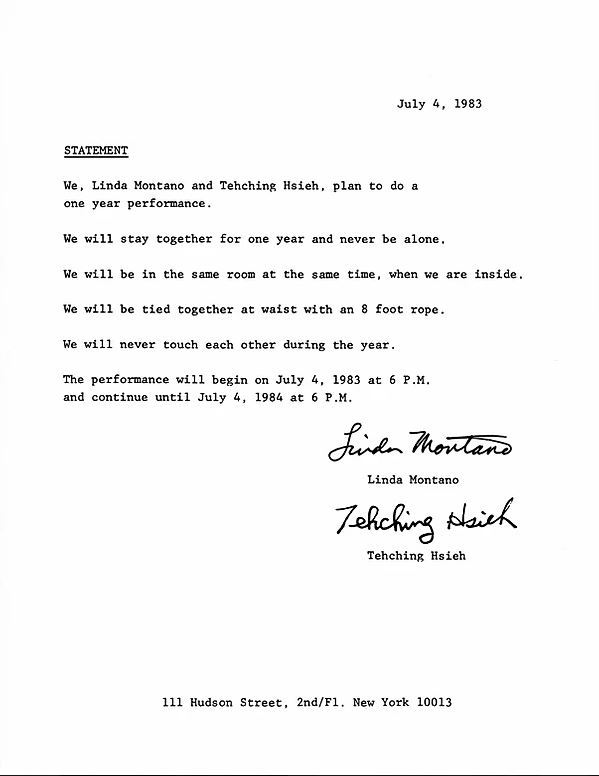

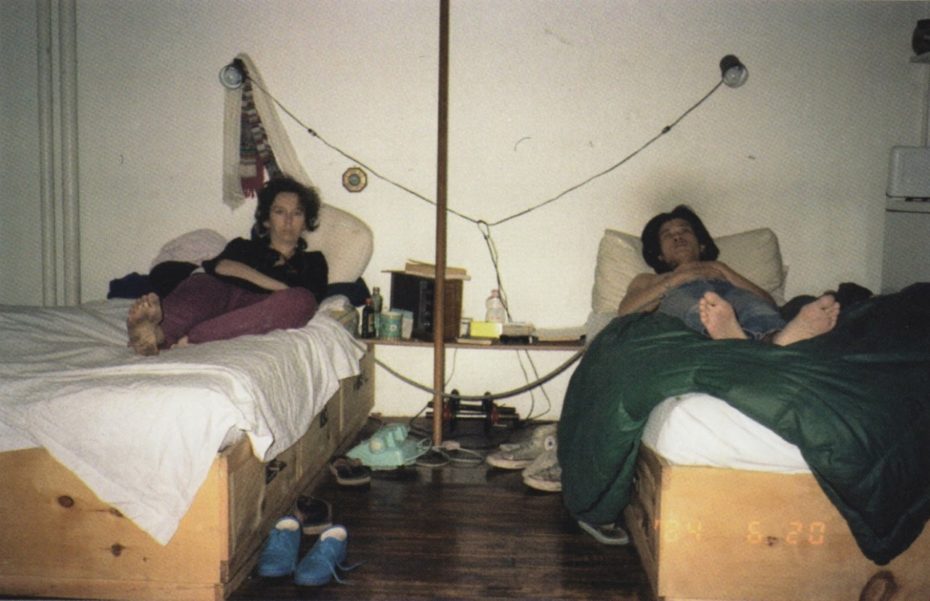

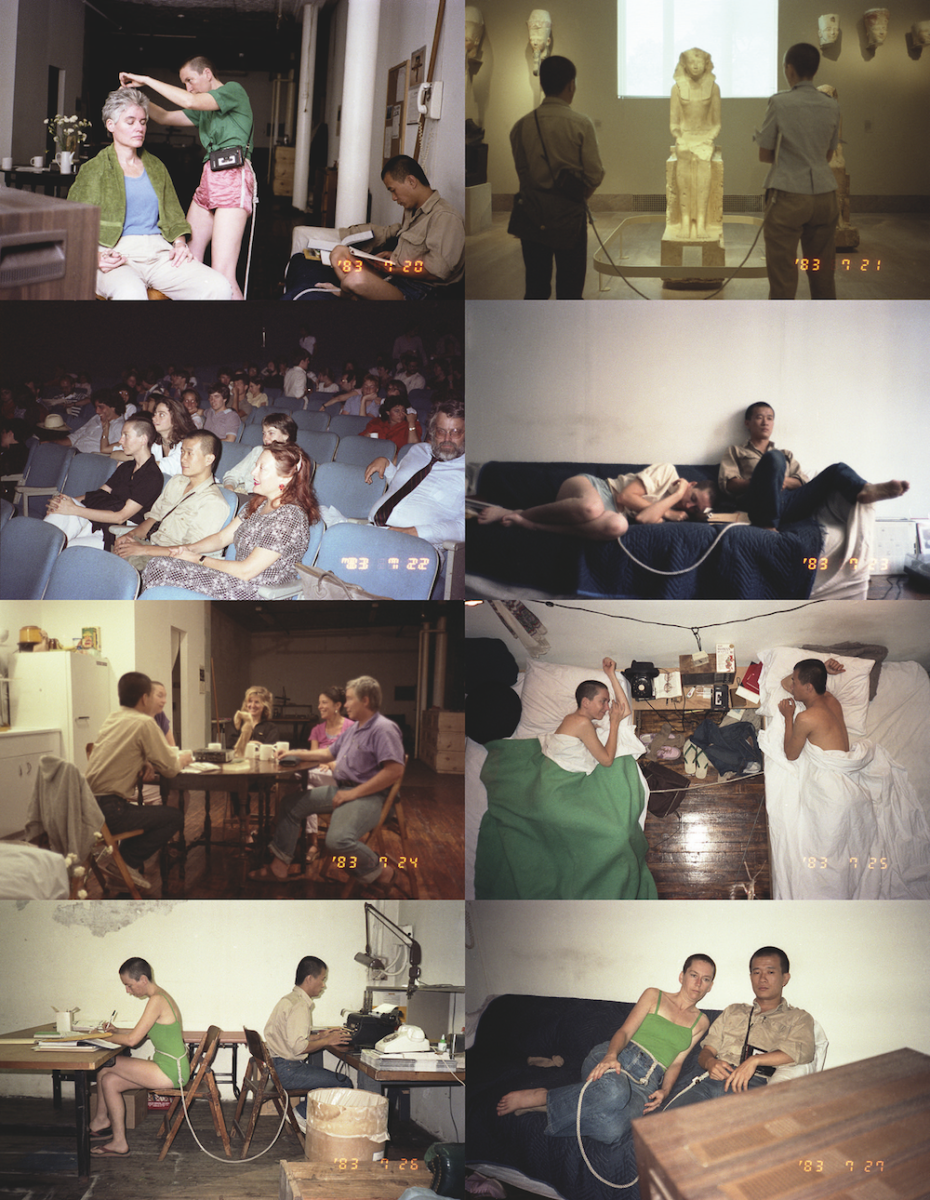

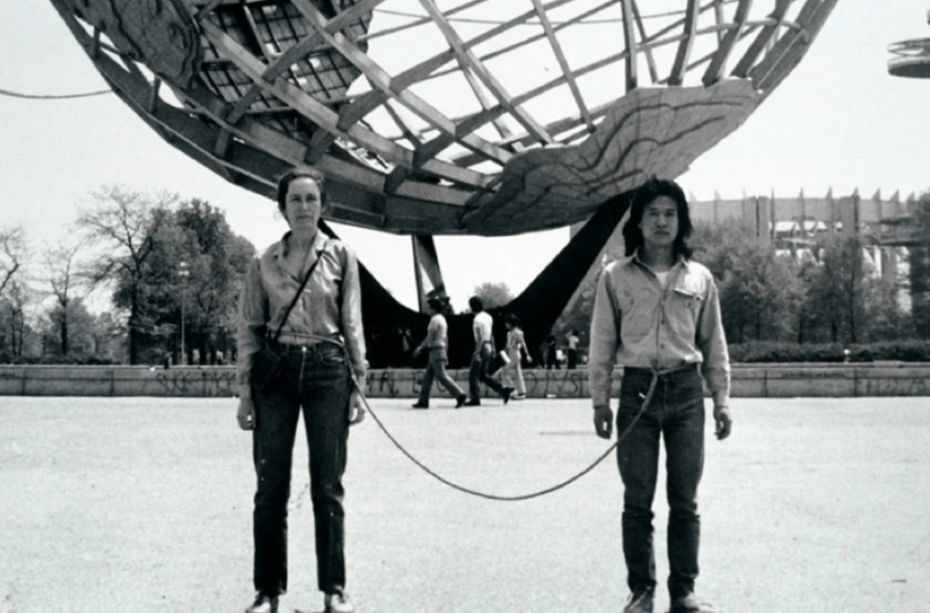

The promise was made on American Independence Day, 1983. “We, Linda Montano and Tehching Hsieh, plan to do a one year performance. We will stay together for one year and never be alone…tied together at [the] waist with an 8 foot rope.” Arguably the most difficult part of this promise? That artists Hsieh and Montano would “never touch each other during the year.” Decades later, their “Rope Piece” project resonates with us on an almost prophetic, eerie level – as if we’re glimpsing into the rearview mirror to see social distancing before it was co-opted by Covid-19. At time when we all continue to reflect on the distance between us, what can we learn from Rope Piece today?

Rope Piece was a real time collaboration – a combustion, you could say – of two individuals’ thoughts, feelings and good old existential baggage. Hsieh, who spearheaded the project, cites Franz Kafka, Dostoevsky, and Existentialism as his influences; arguably the right fuel to spend time, 24/7, tethered to a new friend in New York City.

“I was living in a Zen Center in upstate New York,” explained Montano about their meeting in a joint interview with Hsieh for Public Collectors after the project’s completion. “He said that he was looking for a person to work with… I was looking for him… So we continued negotiating, talking.” The terms of agreement: no leaving one another’s side (courtesy of an 8ft rope), and no touching until 1984.

Why, you may ask? Hsieh was craving an experience that could force him to confront all of his weaknesses and insecurities within human relationships, and communication. “I wanted to do one piece about human beings and their struggle with each other. We cannot go into life alone, without people. But we are together so we become each other’s cage.”

When you’re tied to another person like that, you’re presented with a unique opportunity to explore emotions that suddenly feel twice as a raw. “I believe if life is hard,” he said, “and if I choose to do something harder, then I can homoeopathically balance the two difficulties. Snake venom is used to cure snakebites!”

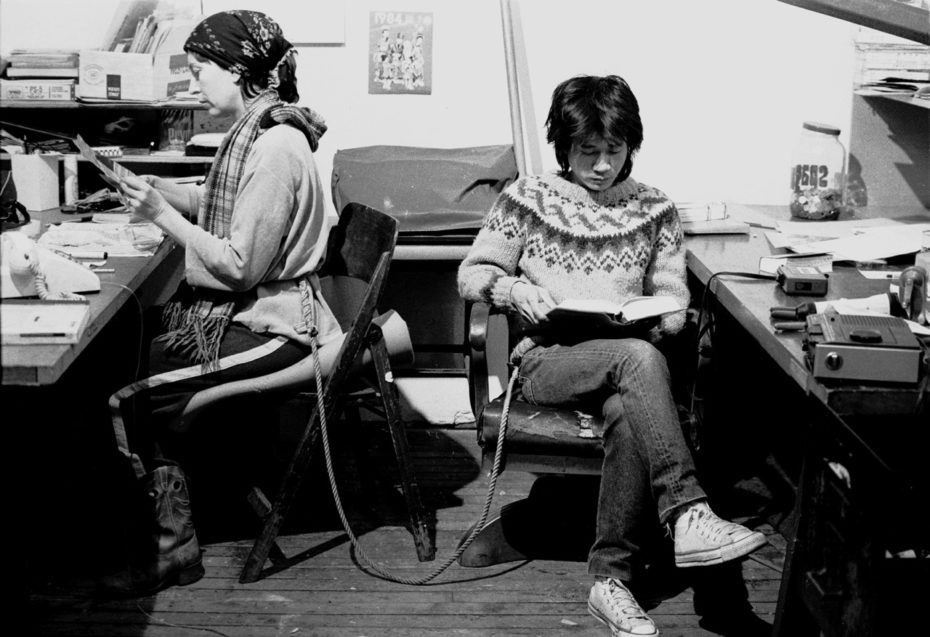

The regression of their communication was evolved from hours long conversations into angry rope tugging, and eventually communication, mostly by grunting. “This piece is about being like an animal, naked,” Hsieh said, “We cannot hide our negative sides. We cannot be shy. It’s more than just honesty — we show our weakness.”

Linda used the experience to form a bond with Hsieh that shattered social norms. “He’s my friend, confidant, lover, son, opponent, husband, [and] brother,” she said, “playmate, sparring partner, mother, father, etc. The list goes on and on. There isn’t one word or one archetype that fits. I feel very deeply for him…”

“I think Linda is the most honest person I’ve known in my life,” Hsieh concluded, “and I feel very comfortable to talk — to share my personality with her. That’s enough. I feel that’s pretty good. We had a lot of fights and I don’t feel that is negative. Anybody who is tied this way, even if they were a nice couple, I’m sure they would fight too.”

Towards the experiment’s end, there was a massive energy shift. “80 days before the end, we started to act like we were people. It was almost as if we surfaced from a submarine.”

Together, they emerged from that isolated confinement, proud to have braved alternative, deeper levels of connectivity. “Since the body isn’t touched,” she explained, “the mind is pushed into the astral.”

Montano’s life has always been anchored by a deep fascination with spirituality and ritual. She was born in 1942 in upstate New York to a family of devout Roman Catholics, and told Art Practical in 2015 that “the spiritual quality of the Mass so influenced me that I then wanted to live in that world. I wanted to find ways to make it happen, over and over and over, because it is a wonderful high.” But the rocky evolution of her Catholic faith, and of her spirituality in general, awakened something else inside her.

“Had I grown up in a culture in which ritual and matriarchy were synonymous,” she said, “I would be a different person. I wouldn’t have to be a performance artist.” Often, her work explores how freedom, gendered expression and ritual intersect. Heavy stuff, no doubt. That’s why the bold visual metaphors of both her and Hsieh’s performance art is so great – it makes those topics more accessible. Like, Montano in Bob Dylan drag? Talk about a weekend conversation starter:

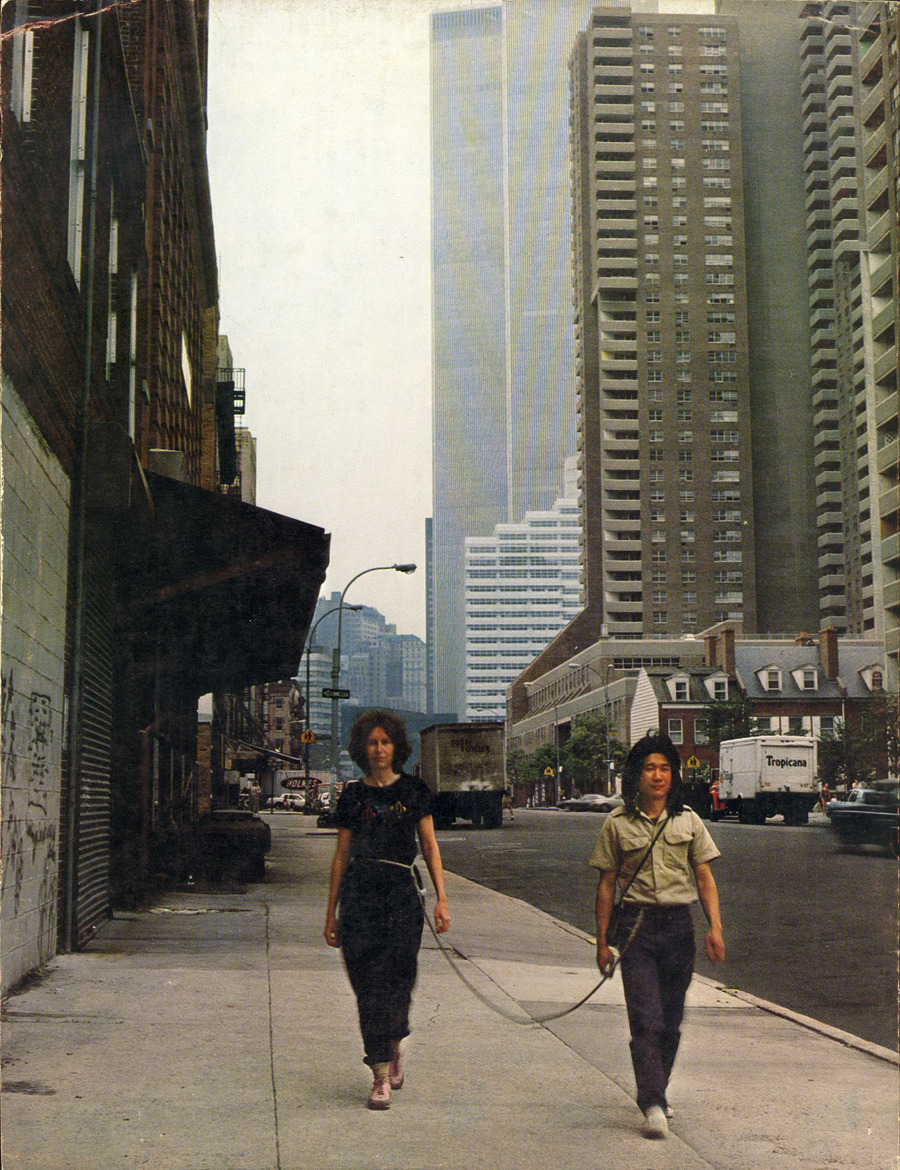

It almost feels like she was cosmically groomed to join Hsieh for Rope Piece. In 1973, she handcuffed herself to a guy for three days to test the limits of shared physical and emotional space; the next year, she blindfolded herself for three days to explore the needs and expectations of human perception. Meanwhile, that same year, Hsieh took one of the greatest risks of his life – and it set him on the path towards Montano. Given that acquiring a visa was pretty much impossible for Hsieh, then in his native Taiwan, the young artist trained as a sailor in order to effectively hitchhike his way by sea to the States. In 1974, he reached dry land in Philadelphia and headed straight for New York City.

Hsieh’s works hinged on deeply physical, personal calls to action. At 23 years-old, for example, he photographed himself jumping out of a window.

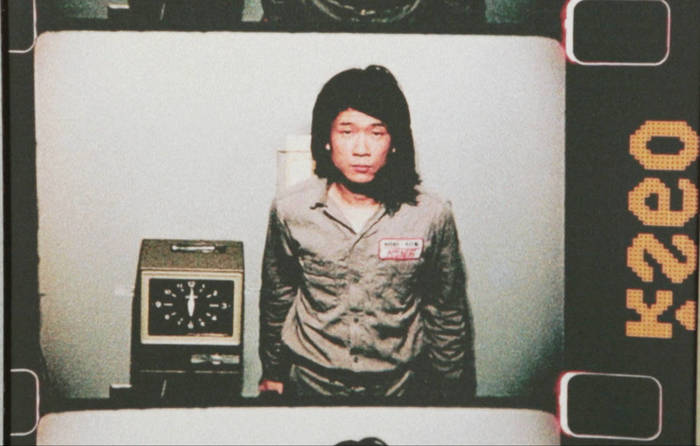

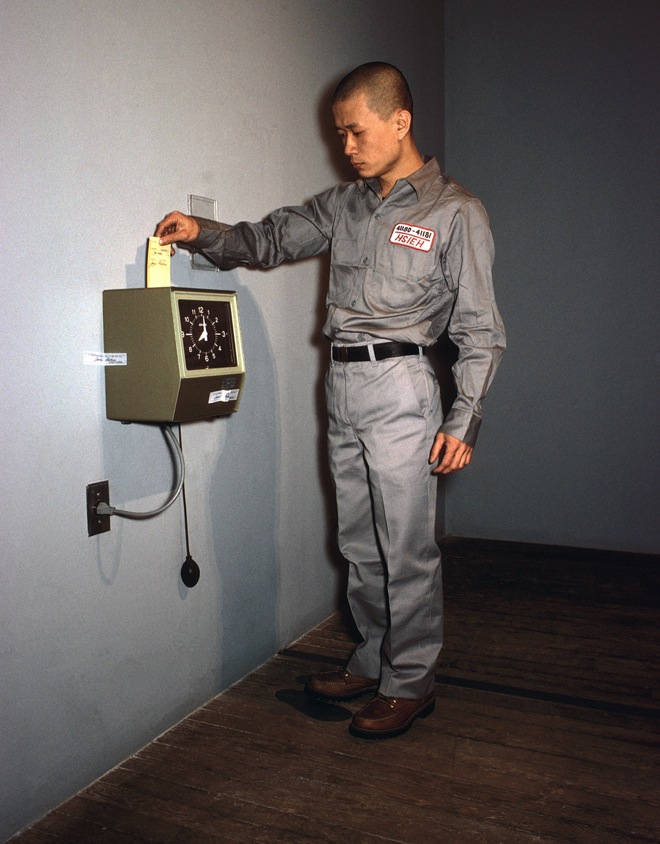

New York City didn’t just provide a backdrop for his work. As an illegal immigrant (he was granted amnesty in 1988), Hsieh found work where he could in restaurants, making little money for a lot of hustle. He also lived in fear of the police, seldom took the subway, and didn’t mingle with the rising art scene darlings downtown. Instead, he worked with the material he had: time, space, and action. He spent a year living out on the streets, for example, eventually getting arrested for vagrancy. He spent another year punching a time clock every hour, on the hour, without fail.

“Basically, I use time,” Hsieh told the Chinese magazine Ran Dian in 2015, “But I felt good doing my work in an illegal context; it was difficult, but I had some kind of freedom.” Like Montano, he toyed often with that freedom in a way that is still prompting us to consider issues surrounding social justice, labor, and empathy. For the duration of 1978, for example, he enclosed himself in a wooden cage with no entertainment or human connection (other than a friend who would deliver food and remove his waste). Come 1983, he dreamt up Rope Piece – and what luck, that Montano came serendipitously knocking to work with him.

When all was said and done, Hsieh and Montano were left with a bond so deep, it transcended the physical. On a philosophical level, Hsieh said their piece also didn’t end when they untied the rope. “It’s just that we are talking to each other psychologically. When we die it ends. Until then we are all tied up.”

Montano continues to teach and create art, but Hsieh stopped working in 1999, declaring his creative goals fulfilled. Personally, we’re praying to the art deities for him to grace us with another performance piece, while remaining grateful for the ways in which he pushed performance art boundaries with Montano. Both of these artists represent minority voices in a field that has been famously exclusionary of their talents – and the strides they’ve made can’t be celebrated enough.

Visit MoMA’s website to learn more Linda Montano and Tehching Hsieh.