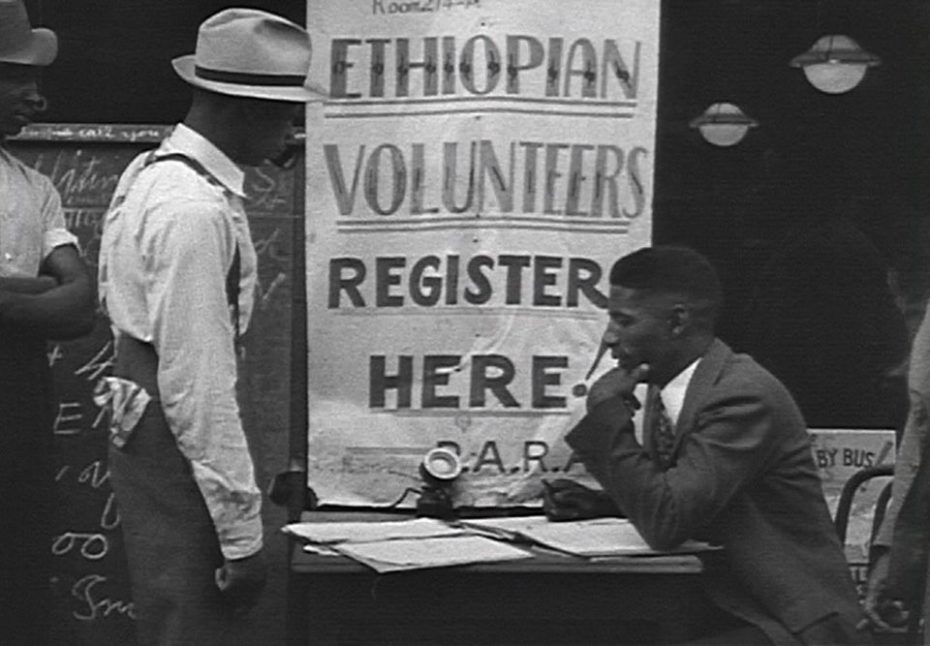

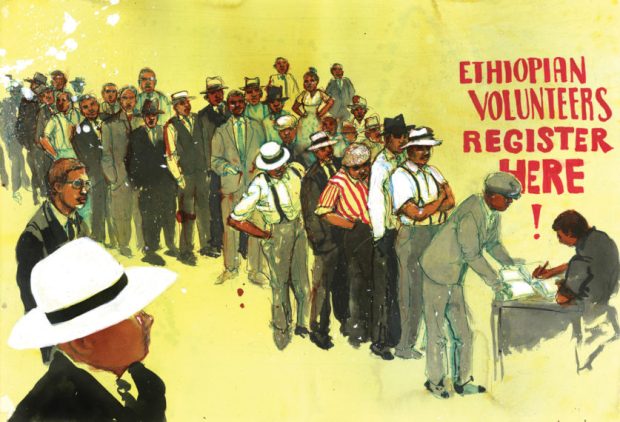

Harlem, New York, the summer of 1935. Years before the United States or even Allied Europe has entered World War II. Large crowds of African Americans are gathering around a registration desk, volunteering to take on a fascist Italian dictator who is soon to become Hitler’s fiercest collaborator. No doubt, Black Americans have enough battles of their own to fight everyday on American soil in the midst of the Great Depression and an enduring Jim Crow era – but news has just come from Africa. The continent’s only remaining nation to avoid colonization in Europe’s Scramble for Africa, has just been invaded by Benito Mussolini. And more than seven thousand miles away, in a historic display of Pan-Africanism and Black Nationalism that took place across the United States, this was the Black American community drafting itself to defend the Empire of Ethiopia when no one else would. Today’s forgotten chapter of history connects to a number of fascinating stories about America’s first Black aviators, taking us from the streets of Harlem to Africa, with an unexpected stop in the English countryside following the little-known footsteps of the last Emperor of Ethiopia (who just so happens to be regarded as the incarnation of God by the Rastafarian religion). Get ready for more fascinating Black History they never taught us in history class…

The rare footage above provides a glimpse into that summer of 1935 when some 20,000 protestors in New York, and thousands others in Boston, Chicago and Detroit, took part in a vigorous campaign to support the Ethiopian plight prior to WWII. Africa’s last sovereign nation was for them, a symbol of redemption in the diaspora; hope for a future of racial equality without being subjects of white colonial ventures.

In the space of about 30 years, between 1881 and 1914, roughly 90% of Africa had been colonized by European nations, but Ethiopia was one of less than a dozen countries left on the world map that had managed to escape foreign control and white supremacist ideology. In a new wave of imperialism, this landlocked country in the horn of Africa had successfully resisted invasions from the British and the Italians once before, who retreated with tails between their legs during the First Italo-Ethiopian War of 1896.

But Mussolini had come back for revenge in August of 1935, this time with a stronger military offence to establish a “modern Roman empire in Ethiopia”, sending its reigning Black emperor, Haile Selassie, into exile. News of the brutal invasion outraged African Americans, many of whom increasingly saw Ethiopia, an ancient cradle of civilization, as their true ancestral homeland. If there was ever a foreign war worth fighting, it was going to be this one. But for the thousands who signed up for the draft (including women, if that rare footage is anything to go by), their efforts would ultimately be in vain….

Almost all volunteers were blocked from leaving by the US government, which threatened imprisonment if they chose to bear arms alongside Ethiopians and adopt their military uniform. According to a federal statute, it was a criminal offence for an American citizen to support any country that was not an ally of the United States. Harlem Renaissance leader and Civil Rights activist, W.E.B Du Bois, argued at the time that Western powers would have responded to the invasion if Ethiopia were a white nation. Demonstrators faced hostile pushback from the police, while tensions mounted between the Black community and some 100,000 Italians that originally called Harlem their “Little Italy” until the 1950s. Despite desperate appeals, lawmakers and the State Department successfully prevented all African Americans from traveling to fight under the Ethiopian flag – that is, except for a few brave individuals who slipped under the radar….

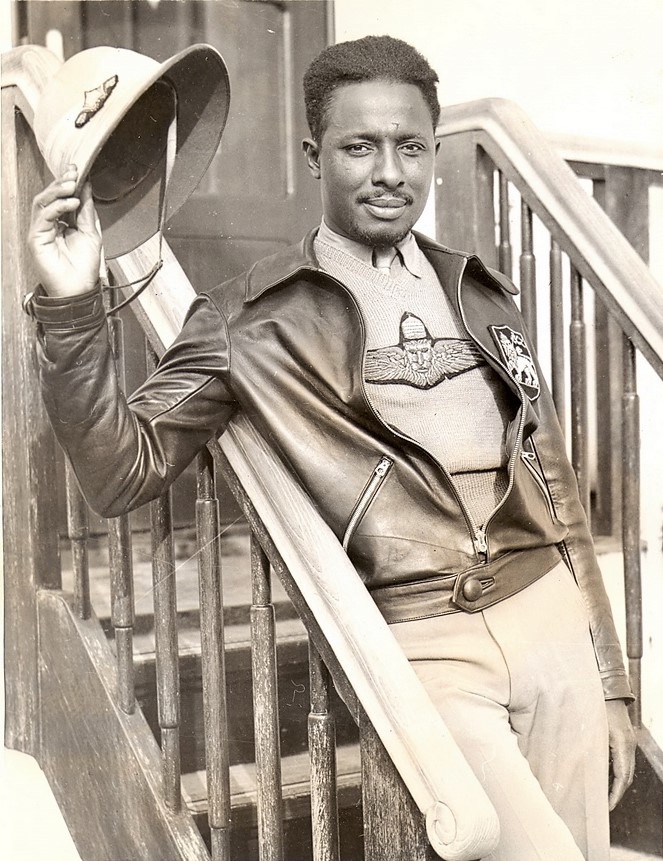

Enter John C. Robinson, a brilliant and highly intellectual aspiring pilot who had earned his flying credentials while working as a janitor for the Curtiss-Wright School of Aviation in Chicago. He had been repeatedly denied entry as a student to the all-white school, but found his way in by cleaning classrooms, allowing him to eavesdrop on night classes. An instructor finally took notice of John when he built his own airplane. Intrigued, the class tested out his plane, ultimately offering him a place as the school’s first Black student. After graduating, Robinson decided he should serve as a pioneer in Black aviation and teach others to fly.

He would be following in the footsteps of daring “wing walker”, Bessie Coleman, the first African American woman to hold a pilot license, whose dream of opening a flight school for non-whites was tragically cut short when she fell from an airplane at the age of 34. Fulfilling Bessie’s goal became Robinson’s personal mission, along with another aspiring aviator and mechanic, Cornelius R. Coffey, with whom he had built his first plane.

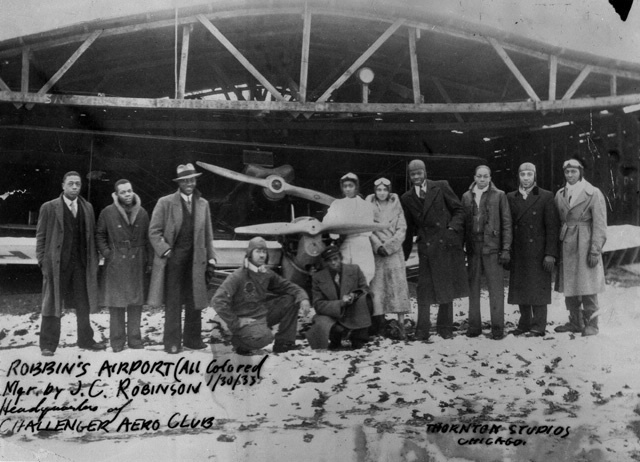

To achieve this in a country that would not allow people of colour to fly, they would essentially need to their own private airport. And so in 1931, with the help of some volunteers, the two auto mechanics-turned-aviators built America’s first Black-owned airport in the predominantly Black town of Robbins, Illinois.

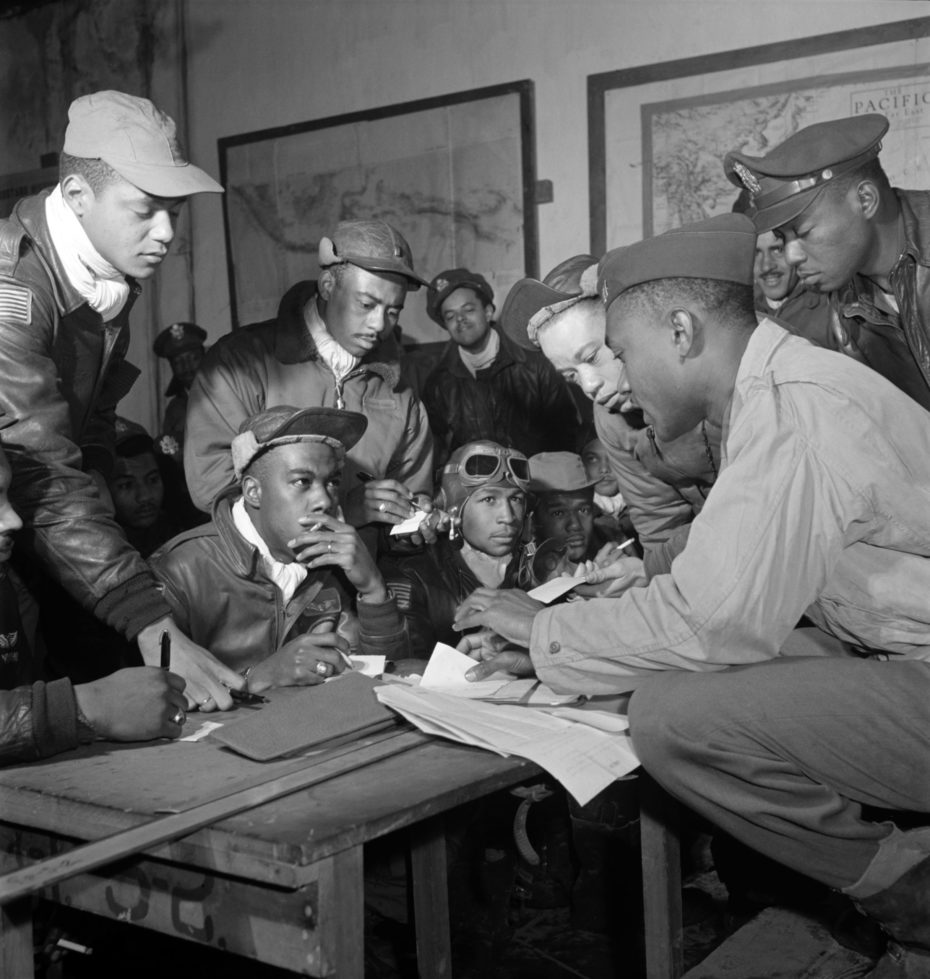

Their earliest students were mainly guys from Coffey’s Chicago garage as well as five women; including Janet Waterford Bragg and Willa Brown. Janet would become the first African-American woman to hold a commercial pilot license while Willa helped Robinson open up the US armed forces to African Americans, eventually enabling an all-Black military pilot group to serve in WWII, known as the Tuskegee Airmen:

In 1935 however, no African-American had ever been trained as a US military pilot. Robinson’s club of Black aviators trained themselves hard anyway, and when they heard of Ethiopia’s plight and the efforts to organise an Ethiopian air force, they longed to become a part of it. Robinson announced his intentions to volunteer and soon enough, word of the American aviator and activist, hailed as the “Brown Condor”, reached the African continent. Ethiopia’s then Emperor, Haile Selassie, wired an official invitation to Robinson. Out of thousands who had volunteered, he was one of just a handful of Black Americans to successfully make it to Africa.

He joined another aviator, Hubert Julian, dubbed “The Black Eagle of Harlem”, who had already made several trips to the Ethiopian Empire, but the two airmen quickly clashed in a very public spat at the Hotel de France in the capital of Addis Ababa. Displeased with Julian’s treatment of his new guest, the Emperor made Robinson commander of the Ethiopian Air Force instead. Suddenly, John C. Robinson, a shoeshiner from Florida who had earned his wings while wearing a janitor’s uniform, was now leading Africa’s best chance to save its last sovereign nation. The air force consisted of 50 pilots and just 20 planes, all of them weaponless. They were ultimately outmatched by the Italian airforce. After a devastating Italian bombing of the city of Adwa, Robinson wrote, “I saw a squad of soldiers standing in the street dumbfounded, looking at the airplanes. They had their swords raised in their hands.”

In May of 1936, Italy annexed Ethiopia and Mussolini promptly declared it part of his own “Italian Empire”. Robinson returned to the United States and the Emperor Haile Selassie was forced into exile, travelling to Jerusalem, before eventually settling in England. This brings us to his own story…

Born Lij Tafari Makonnen, as a young governor in Ethiopia at the turn of the century, he had become known as Ras Tafari, Ras translating to “head”, similar to the noble ranking equivalent of Duke. Around the same time, a Black rights campaigner and philosopher of the “Back-to-Africa” movement preached to his followers to “look to Africa when a Black King shall be crowned, for the day of deliverance is at hand”.

In the 1930s, when Ras Tafari was crowned as the Emperor of Ethiopia, and took the name Haile Selassie, which means power of the Trinity, a growing religious group in Jamaica saw this as the messiah returned to earth. And a movement, now most famously associated with Bob Marley, known as Rastafarianism, was born.

Many Rastafarians (although not all), believe that the Ethiopian monarch was the Second Coming of Jesus and the manifestation of God in human form. In a later interview, Selassie was asked about the Rastas’ views about him being the Second Coming of Jesus, to which he responded: “I have heard of this idea. I also met certain Rastafarians. I told them clearly that I am a man, that I am mortal, and that I will be replaced by the oncoming generation, and that they should never make a mistake in assuming or pretending that a human being is emanated from a deity.”

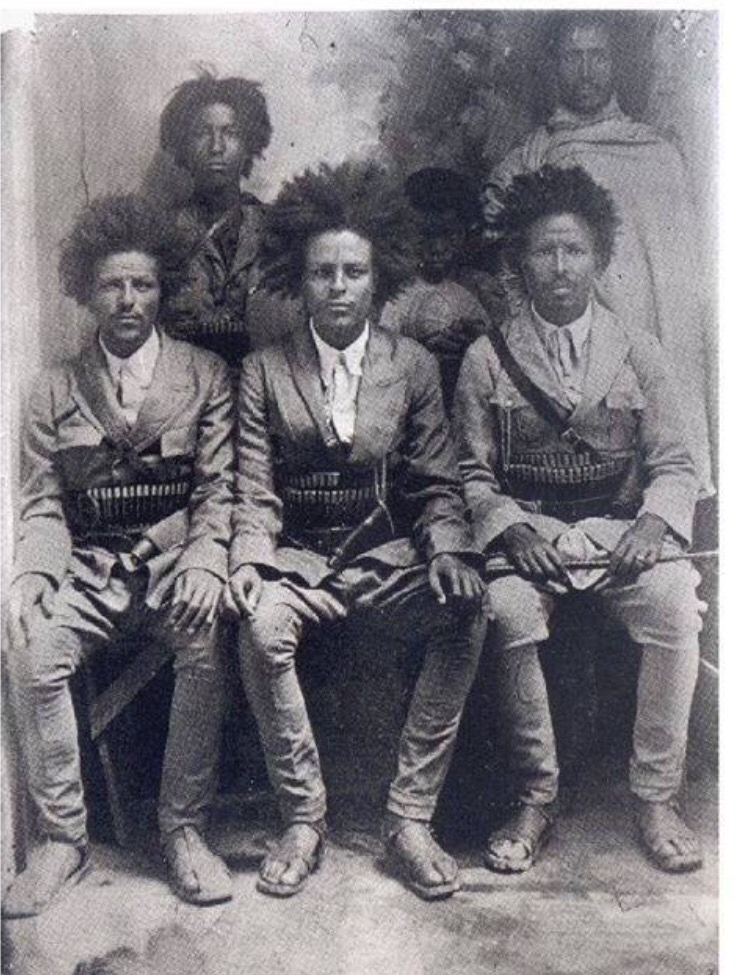

It’s been suggested that the term for “dreadlocks”, which became so symbolic for the Rastafarian movement, comes from the guerrilla warriors who vowed not to cut their hair until Selassie was released from exile after leading the resistance against the Italian invasion. Because the warriors with locks in their hair were “dreaded” by European colonial soldiers, this is possibly how the term originated, but the history of the name remains unconfirmed.

In 1936, the last of the Solomonic kings found refuge from Mussolini’s fascist invasion in Bath, England, in a two-storey Italianate house, where he lived with his family and staff for five years. The residence, built in 1850, has become the unusual spiritual home for Rastafarians, and to this day, holds sacred value to followers of Rastafarianism.

In this 1999 documentary, Bath locals describe encounters with the Emperor and his reveal the struggle and indignation he faced whilst living in exile:

Britain officially liberated Italian East Africa by 1942, and Haile Selassie was returned to power, seeing Ethiopia gain its independence again in 1944.

After World War II, John C. Robinson returned to the liberated Ethiopia and trained the initial pilots to the newly established Ethiopian Airlines, which was the first, and for a long time, the only African airline. On his Ethiopian Airlines flight to Addis Ababa, Nelson Mandela was surprised to find a Black pilot in the cockpit, the first he had ever seen. The airline remains one of Africa’s commercial aviation giants today.

Haile Selassie was murdered at the age of 83 by communist military revolutionaries. The year before, he had flown to Washington to request support from Nixon, but was denied. Selassie’s legacy (which you can learn more about here) remains divisive, but some Rastafarians still believe in his immortal presence and that they will one day return to the promised land of Ethiopia to live in peace and freedom.

“Throughout history, it has been the inaction of those who could have acted; the indifference of those who should have known better; the silence of the voice of justice when it mattered most; that has made it possible for evil to triumph.”

Haile Selassie