During his lifetime, Congolese sculptor Bodys Isek Kingelez, did not have a commercial art dealer to represent his work. The self-taught visionary reimagined glittering global capitals for a post-colonial Africa, and made hundreds of “extreme” miniature architectural models throughout his career, which was cut short in 2015 following his battle with cancer. A few years later in 2018, one of the largest and most influential art museums in the world gave him a posthumous exhibition, making it the first solo retrospect MoMa has ever organized for a Black African artist to date. In case you missed it, here’s another chance to get to know the work of Bodys Isek Kingelez…

Bodys came of age at a pivotal moment for his country, now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo, which gained independence from Belgium in 1960. He found a job as a secondary school teacher in the capital of Kinshasa during an era of de-colonisation. This was a moment for his country to build an identity, and this was a man that not only wanted to be a part of that, but wanted to design it himself.

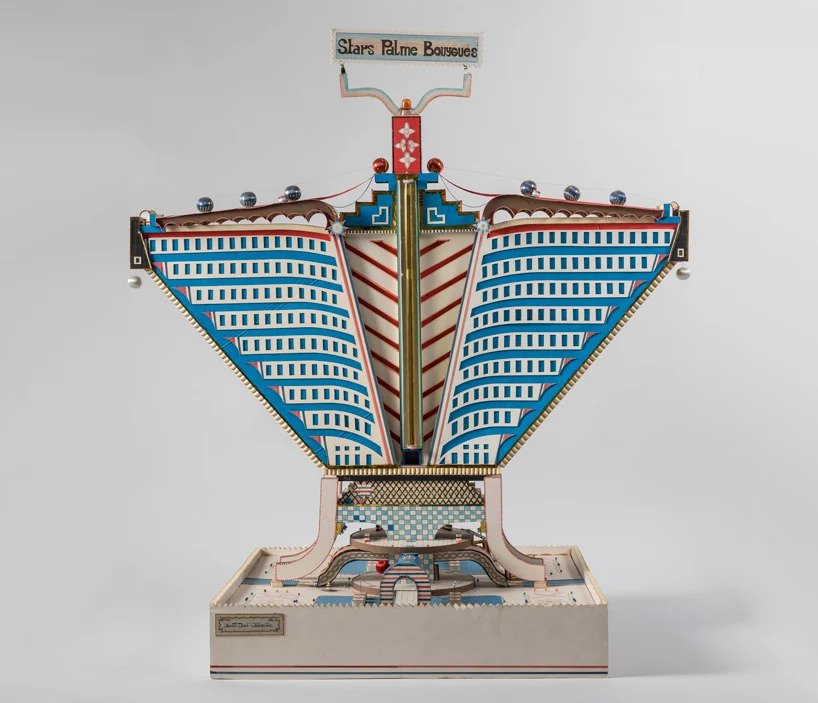

In the 1980s, he began collecting discarded materials, from plastic and paper to coke cans toothpicks and bottle caps in order to craft models of buildings as he wished them to be in his post-colonial Congo. A neighbour soon noticed his talent and suggested Bodys show his models to the Musée National, where his work was met with disbelief, literally.

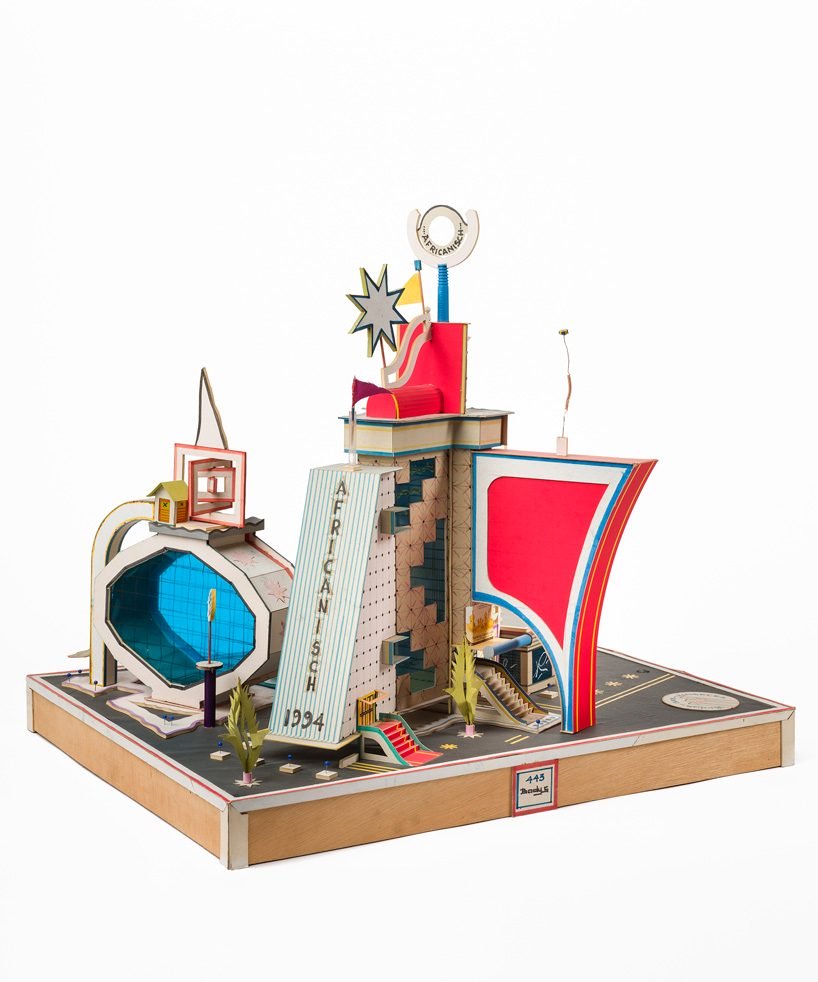

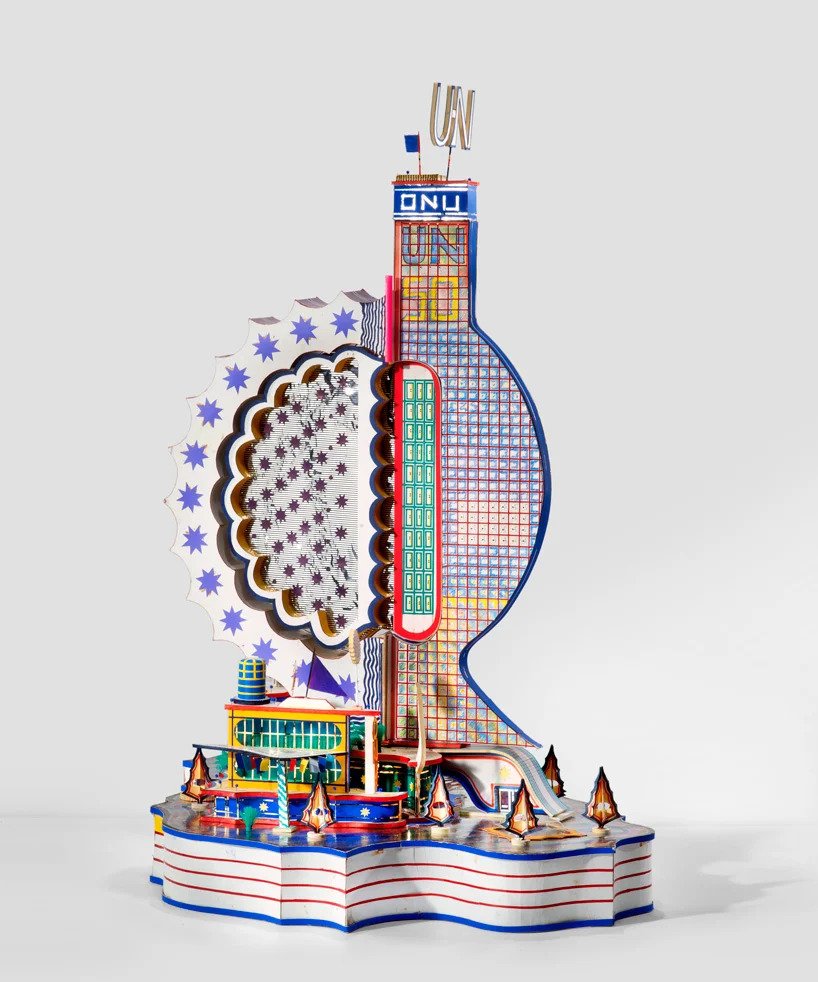

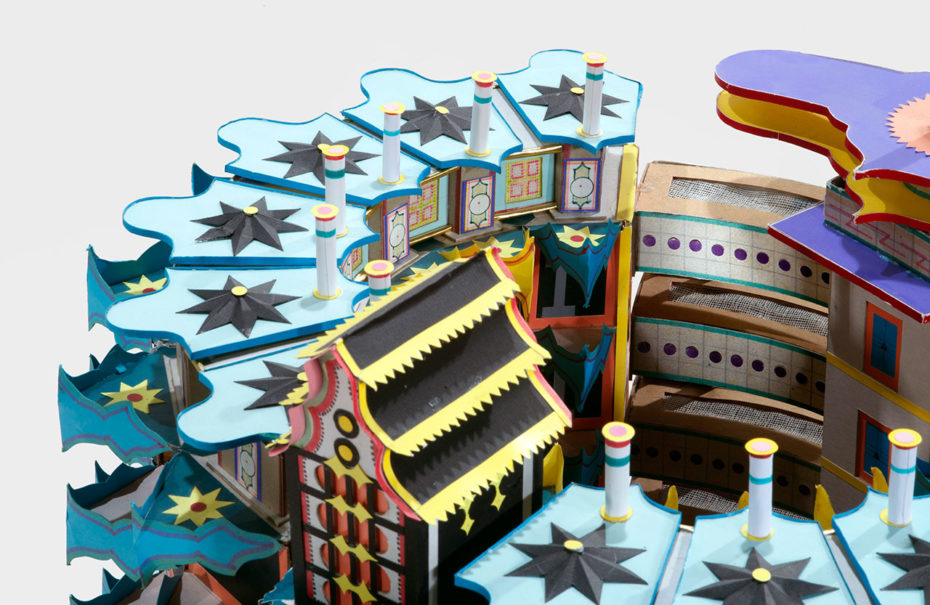

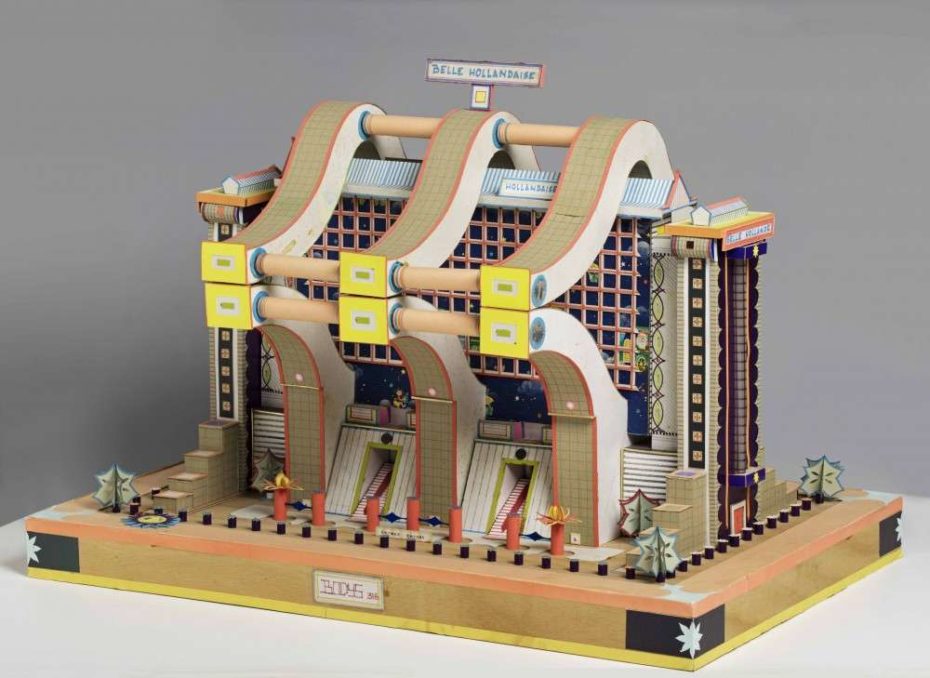

Unable to believe that this school teacher from a small agricultural village had created such elaborate sculptures, the museum board requested he prove he was the artist and recreate a mode in front of them. Satisfied, they offered him a job in the archives as a restorer of traditional objects for the museum’s collection, without recognising his potential to become one of Africa’s greatest contemporary artists. In his spare time, Kingelez continued sculpting his models, graduating from building single buildings to entire rainbow-hued cityscapes.

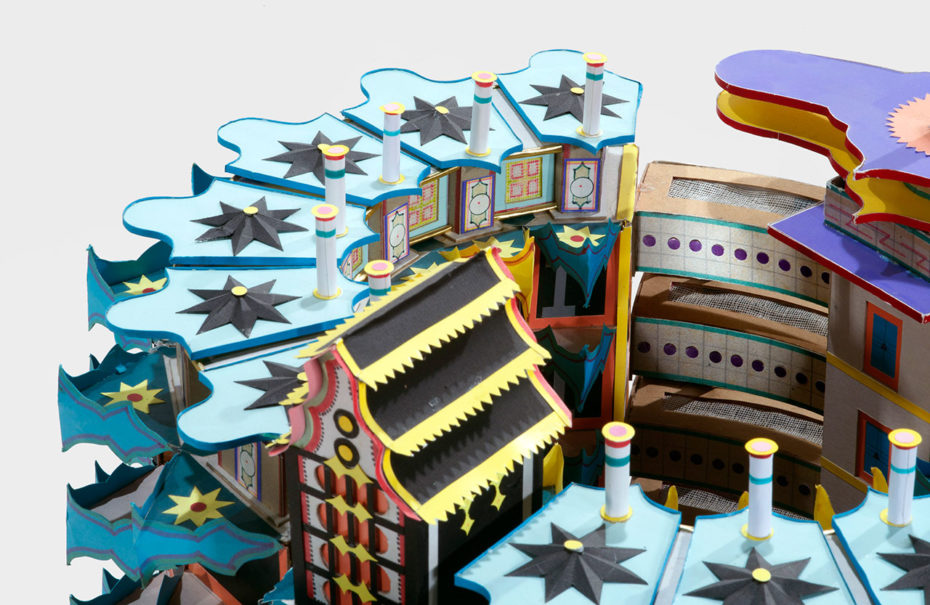

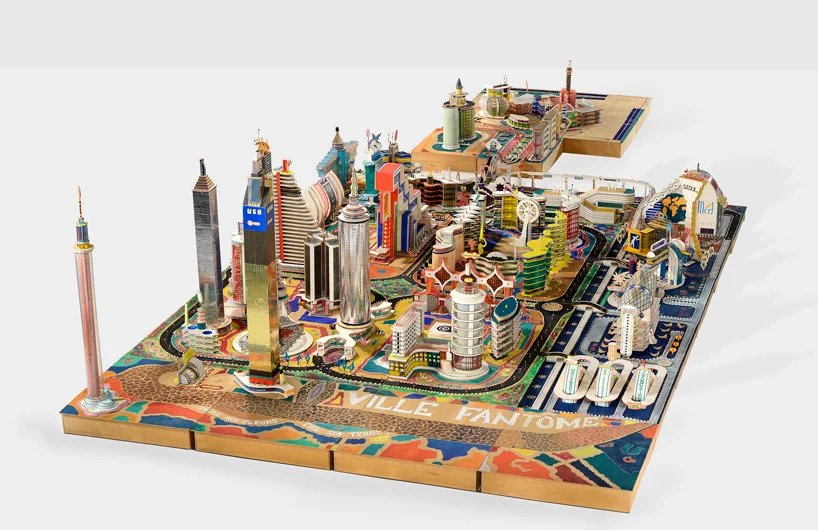

While reminiscent of elements from Ettore Sotsass’ 1980s Memphis Group and the spaceship palaces of Bolivian architect Freddy Mamani, his models are like nothing you have ever seen before. The slums of Kinshasa became colourful utopias of and possibility, complete with numerous flamboyant buildings, avenues, parks, stadiums and monuments. He turned the agricultural village where he was born into a miniature metropolis reminiscent of Las Vegas’ golden age of Googie architecture.

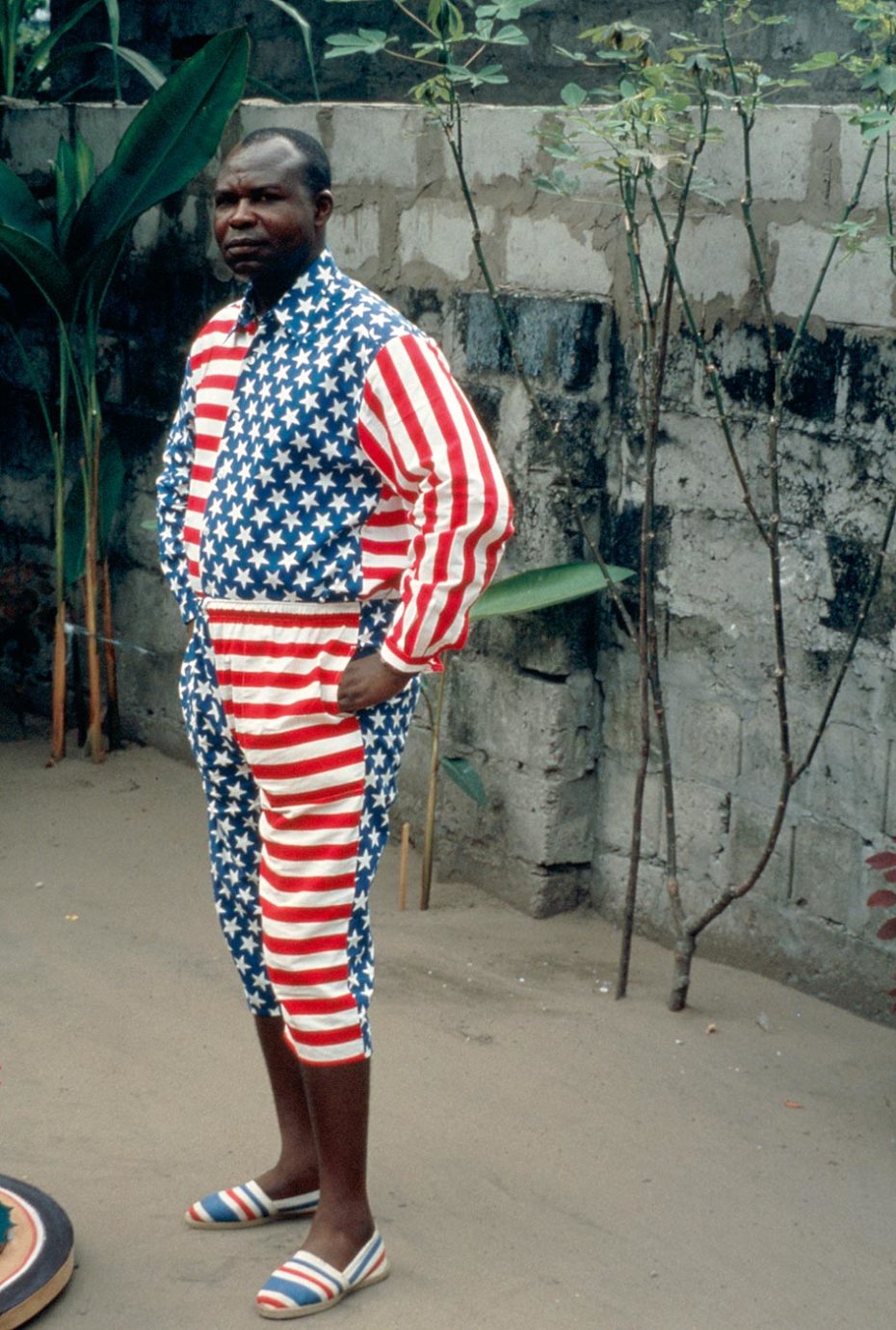

Despite his humble origins, Kingelez was well-educated and considered himself a worldly man. He dressed in a similar fashion to the Sapeurs, a Congolese subculture of extraordinarily dressed dandies who defied poverty and their war-torn surroundings.

In the late 1980s, his work was noticed by a French architect who was travelling around Africa. The chance encounter eventually led to an invitation for then-unknown artist to show his work in Paris at the Centre Pompidou. French-Italian automobile heir, Jean Pigozzi became a major collector of what Kingelez called his “extrêmes maquettes“, and his Contemporary African Art Collection in Geneva now holds the largest number pieces anywhere in the world.

“I make this most deeply imaginary, meticulous and well considered work with the aim of having more influence over life. As a black artist I must set a good example by receiving the light which pure art, this vital human instrument, kindles for the sake of all. Thanks to my deep hope for a happy tomorrow, I strive to better my quality, and the better becomes the wonderful. I exhibit a mode of expression which fits me like a glove, and I point out that I am another artist.”

Bodys Isek Kingelez

Thirty years after his first exhibition in Paris, MoMA’s first solo retrospective for a black African artist introduced Kingelez’ tabletop metropolises to the world. The exhibit offered a virtual reality experience which allowed visitors to shrink down to the scale of his cities and roam the streets of the famous “Ville Fantome”, his largest model city at 18 feet long and almost four feet wide.

Although none of his urban fantasies would ever become a reality during his lifetime – Kingelez legacy to this day goes under-recognized in his home country – he was natural-born architect in many ways, as well as a visionary urban planner, engineer and artist. He imagined a utopian Congo that wouldn’t need police, one that had better hospitals for AIDS patients and paved the way for a better future, one soda can and toothpick at a time.

There is a book which was published to accompany the first retrospective of his work, available here. He created over 300 models during his life and amazingly, some of his earlier singular building models are for sale.