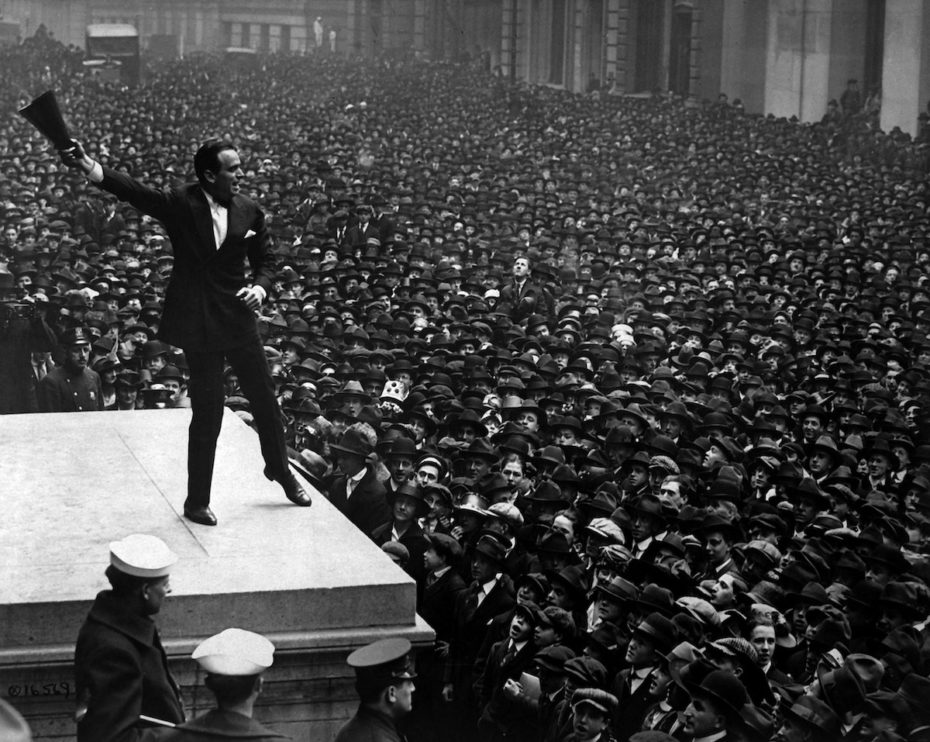

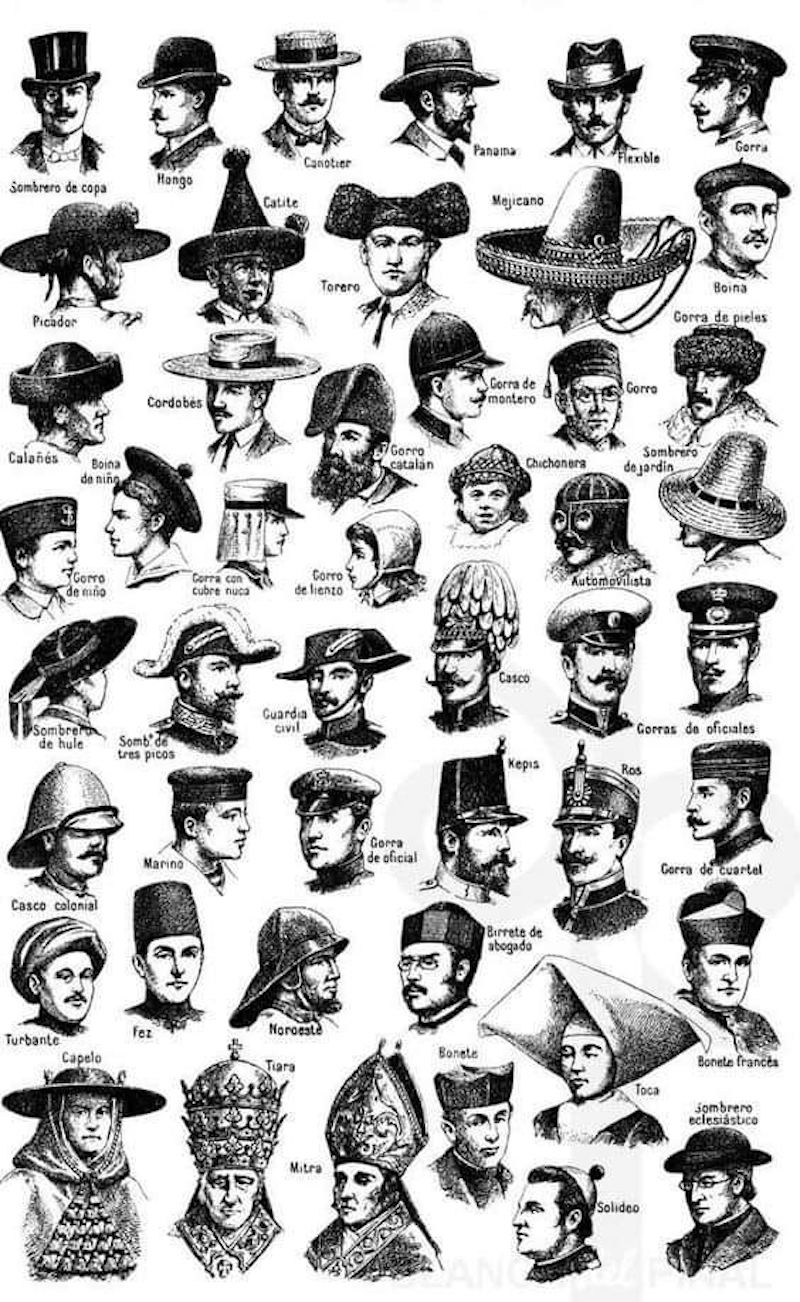

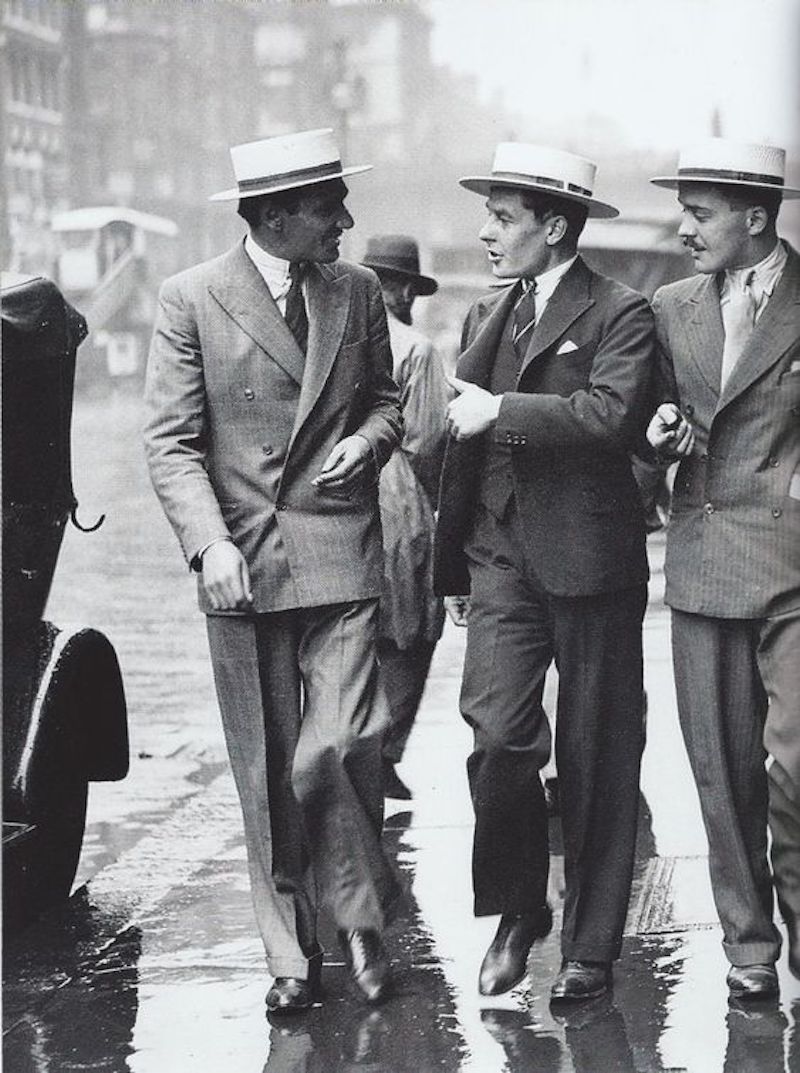

Let’s play a little game of Where’s Waldo? Only, with men who aren’t wearing hats in the above photograph. It raises the question: where have all the elegant fedoras, bowlers, news caps, and top hats gone? Hats have had a role to play for most of our history, walking the line between the utilitarian, decorative, and symbolic. So why did men just stop wearing hats en masse?

One of our biggest clues, as we’ll see later, is that hats were born from two desires: ornamentation and protection. We have pictorial depictions from 3200 BC of an Egyptian man wearing a conical straw hat ideal for keeping ones head cool with its towering form. The Bronze Age’s “Golden Hat of Schifferstadt” is also one of the oldest, towering hats we have found:

The saga of the “Golden Hats” is a very Indiana Jones-y chapter in ancient hat history. Only four have been unearthed to date, each with its own intricate sheet gold construction. Their opulent nature is an important reminder of the ornamental nature hats have played as objects of ceremony and status.

On the other end of the spectrum, in matters of practicality, some historians posit that the Venus of Willendorf might just be wearing the world’s first beanie – and once you see it, you can’t unsee, amiright?!

That’s the magical thing about hats. They offer a curious new way to relive history that feels almost tangible. And while we’d love to get lost in a felty vortex of headgear from 3000 BC to present, we’re going to try to hone in on a few game changers from the last few hundred years…

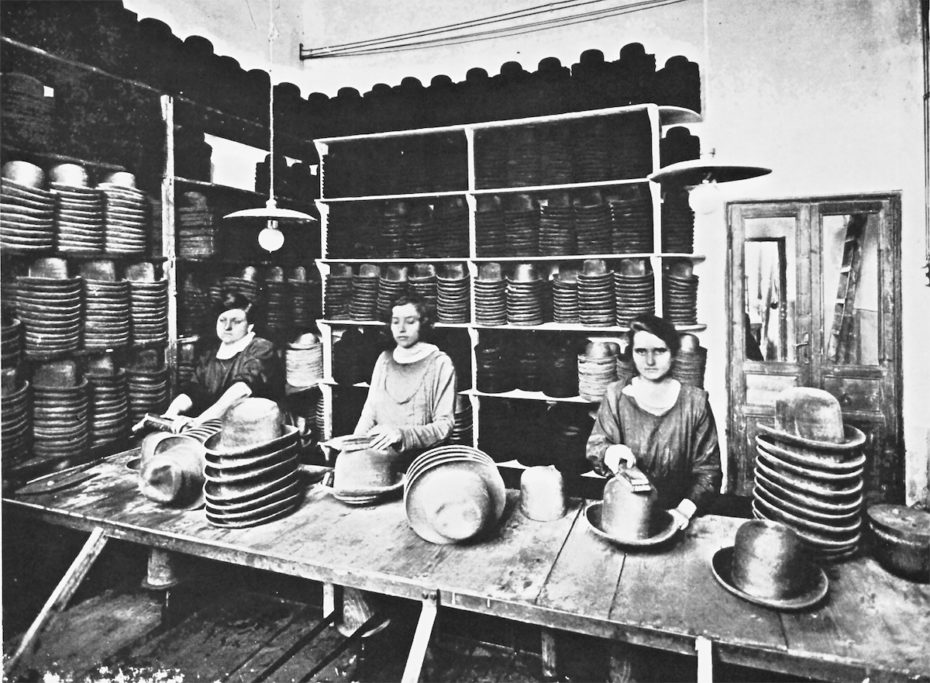

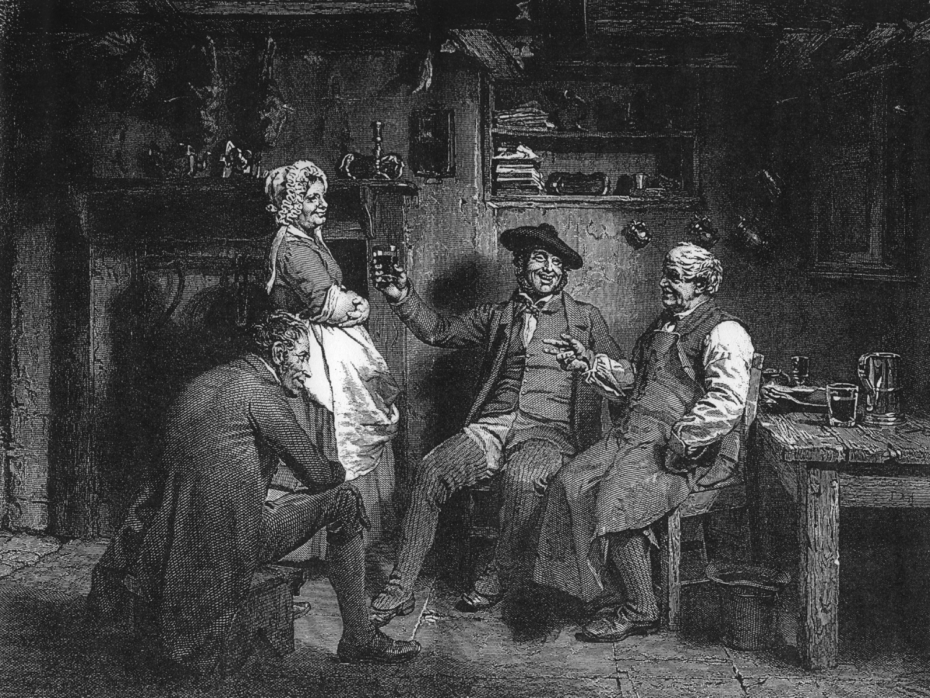

Firstly, did you know that modern hat making was quite a dangerous trade? The expression “mad as a hatter” refers to the mercury poisoning that slowly killed-off so many 19th century hat makers – mercury was used to treat the fibers and improve the felt. Unbeknownst to the hat makers of course, the chemical was causing them to develop all kinds of mental illness, including dementia and erethism.

Then there’s the term “Milliner,” which typically refers to the craft of making hats for women, and was a reference to one of the rising hat epicentres of the world – Milan. (Other than France, Italia was the major fashion city in Europe.)

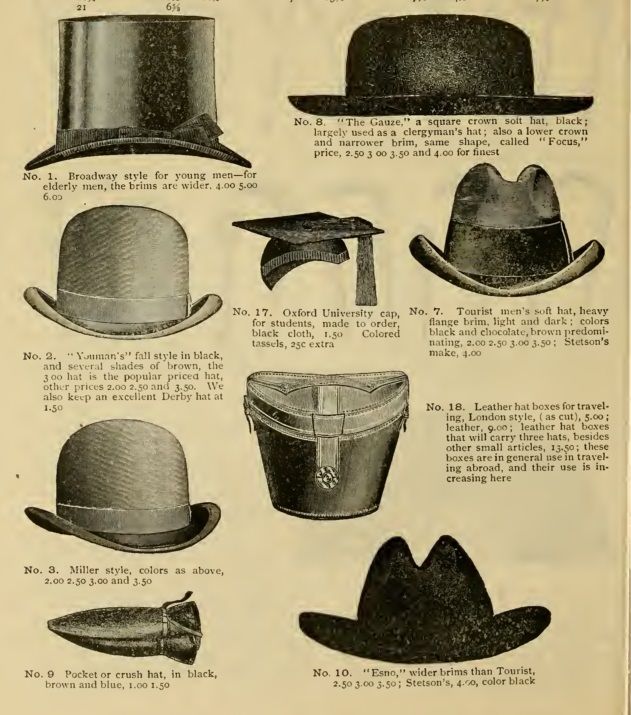

Let’s start with (arguably) the poster child of men’s hats: the top hat. These sky grazing, extravagant hats were made of felted beaver fur or silk, and beloved by fashion dandies – but they were highly controversial to begin with.

“[He] had such a tall and shiny construction on his head that it must have terrified nervous people,” reads one British police report on the first top hat sighting in 1797, which apparently caused a riot, “The sight of this construction was so overstated that various women fainted, children began to cry and dogs started to bark.” The poor top hatted man in question, haberdasher John Hetherington, didn’t just make newspaper headlines – he was posted a £500 bond.

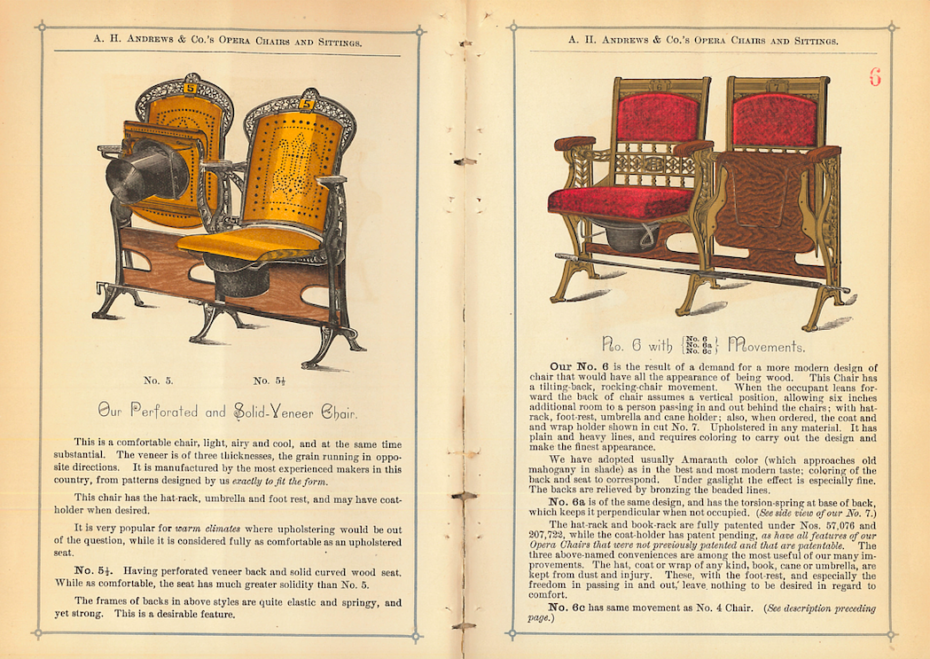

But everyone loves a rebel, right? The top hat’s radical dandyism caught on, and piqued in mainstream popularity by the 1840s-50s. Abraham Lincoln was famously a fan – rumour has it, he hid important letters in its voluminous top. They became such wardrobe staples, that it wasn’t uncommon to find theatres with seats made to accommodate men at the opera…

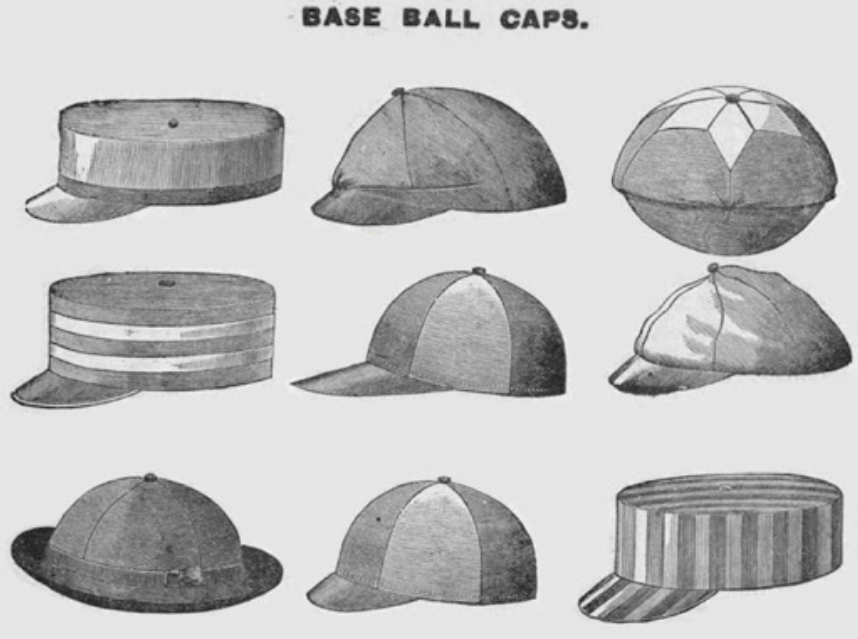

At the same time, the baseball cap was also born in New York City. First, in the form of straw hats donned by the New York Knickerbockers in 1849. Yes folks, you are looking at the original baseball hats:

By 1860, they were even further popularised by Brooklyn’s Excelsiors baseball team uniform. Soon, a variety of “ball caps” started popping up, leading us to the contemporary incarnation we know best.

With its arguably more streamlined and lightweight design, “ball caps” were perfect for men on the move. Branches of law enforcement would also go on to adopt baseball hats. Check out this snapshot of the Cincinnati Reds baseball team in 1888, looking rather more like police officers than a sports team:

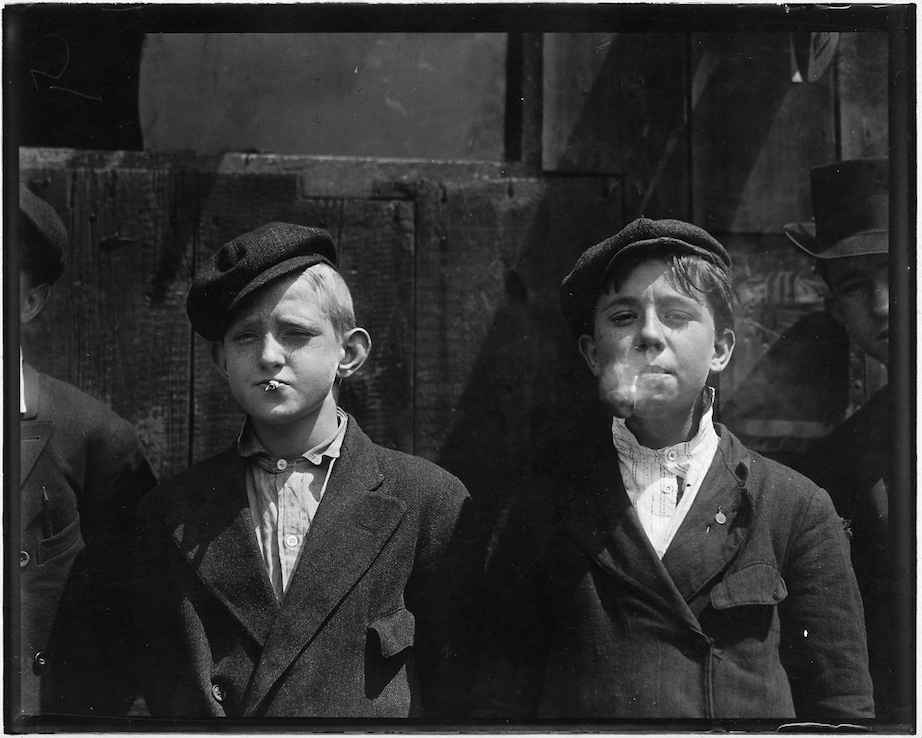

Another iconic men’s hat is the “newsboy cap” – although they weren’t just for newspaper delivery boys, but worn by dock workers, steel workers, and other tradesmen that evolved from the beloved Scottish hat, the Tam ‘O Shanter.

They could be found in every echelon of society, albeit usually as more of a leisure activity accessory (i.e. golfing, a day in the country) for the upper class. Same goes for the ascot cap (think Peaky Blinders), which was usually worn by men working in livestock slaughter in the early 20th century. A hat was a social signifier, identifying a man’s role in society. (Hence idioms like “putting your [insert profession] hat on.” or “he wore many hats” to describe a man of many trades).

As for the good ‘ole cowboy hat? In 1865, a man named John B. Stetson essentially made the first incarnation, known as the “Boss of the Plains” hat. Its design, he said, was made with the needs of the American Western climate in mind – stiff brim, tall crown.

Initially, their indentations and curves were a byproduct of the fact that these were hats that endured a lot. Men would constantly touch, pinch, and fold them as they worked, creating those iconic cowboy shapes. Over time, they became intentional signifiers of a certain ranch or community. There was New Mexico’s “Carlsbad crease” style and the “Montana Peak,” the latter of which was derived from the Mexican sombrero, and had four top dents from being pinched up top by four fingers. To this day, however, Stetson remains the gold standard for cowboy hats. Remarkable, how some things don’t change.

Contrary to popular belief, the cowboy hat might not actually have been the most prevalent out West. A 1957 article in Desert News posits that such a title belongs to the British bowler hat.

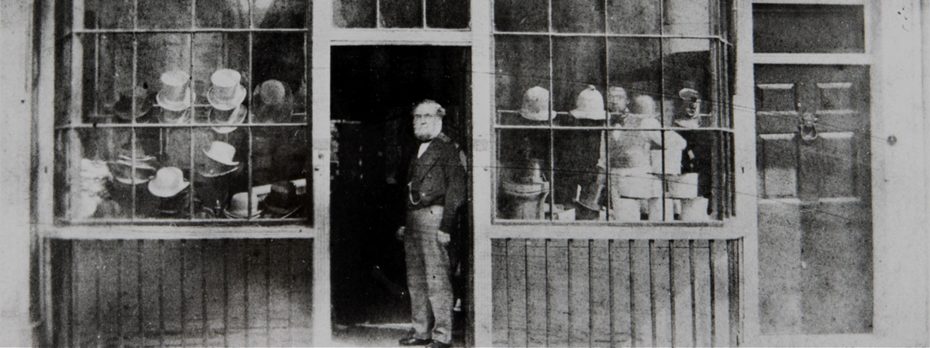

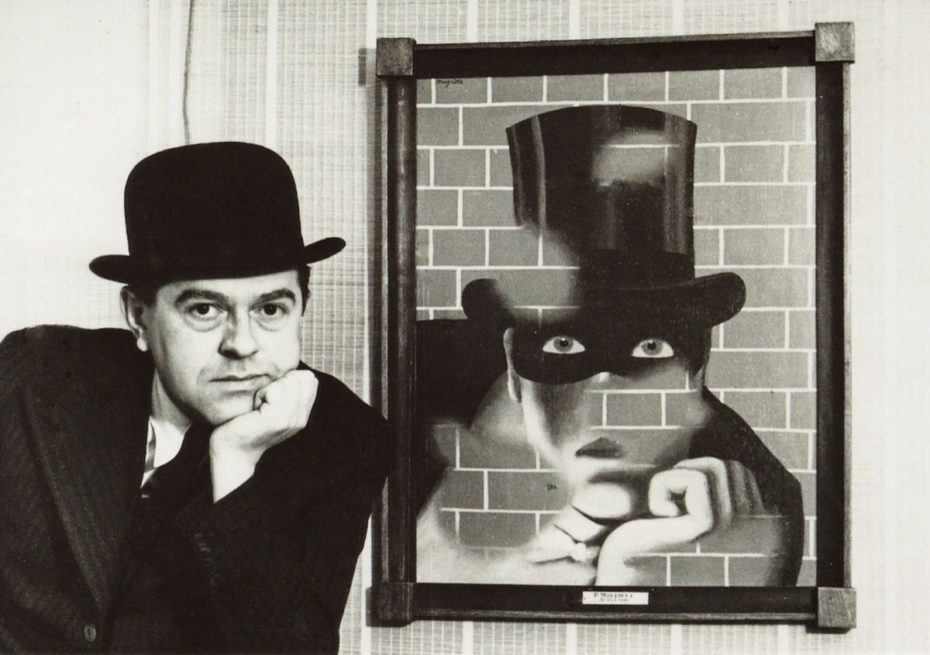

It was created in the London atelier of Thomas and William Bowler in 1849, and deemed a protective, durable, yet stylish option for anyone looking to walk the semi-formal line. “The hat that won the West,” newspaper headlines declared. The shop that created the bowler (pictured above) is in fact still around today, founded all the way back in 1676, making it the World’s Oldest hat shop. Part of what fascinated Rene Magritte so much about the bowler was its “Everyman” appeal:

Evidence of the bowler’s spread can be traced all the way to South America, where it has become a staple of Quechua and Aymara women for a century, when British railway workers arrived in the 1920s. Legend has it, a shipment of bowlers arrived that was much too small for rail workers, so they sold them off to cholitas. That’s the legend, anyway. Today, wearing a bowler or bombín in Bolivia tells the story of that complicated past, as well as the strength and survival of indigenous women who have woven them into their own story.

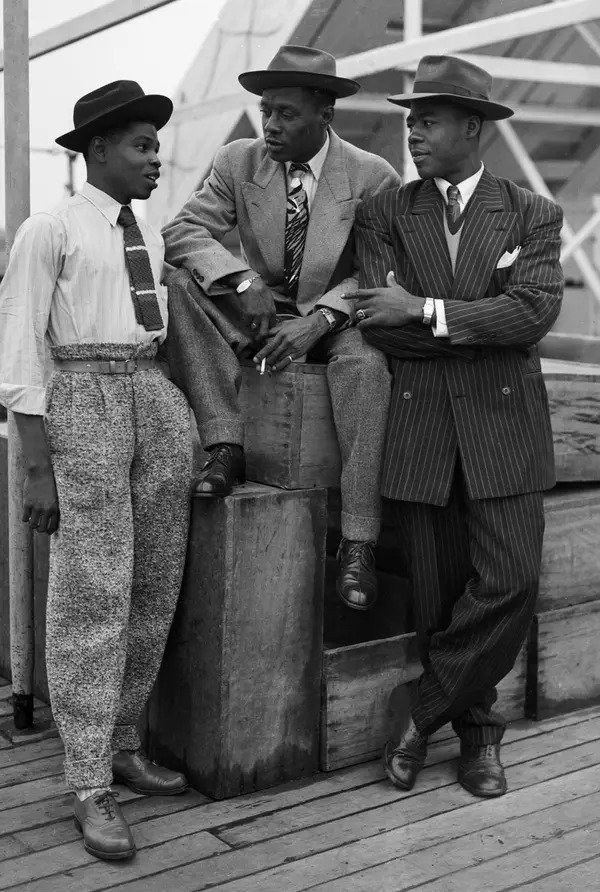

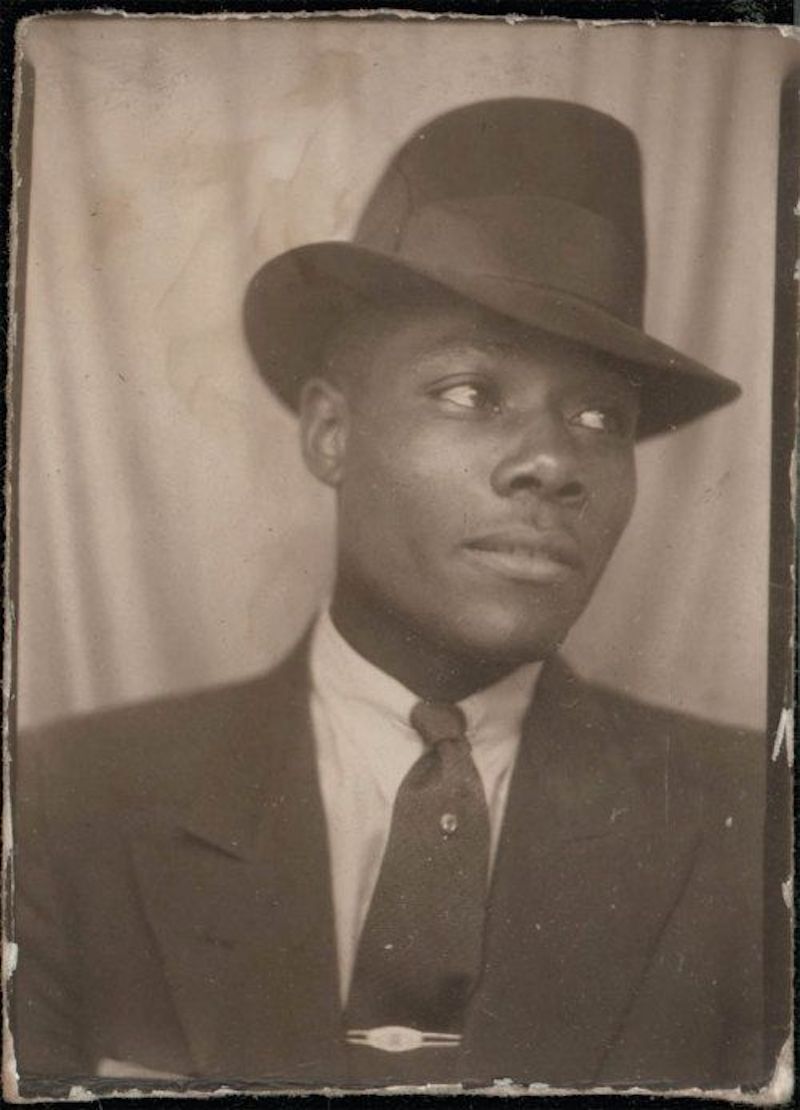

It brings to mind the role hats have played as tools in colonialism, in the military, and in grassroots activism. Who could forget the berets of the Black Panther party, or Che Guevara? Perhaps lesser known: the wonderfully wide brimmed hats of 1940s “Zoot Suits” worn by Mexican and African Americans. The style was so revolutionary, they were actually banned in America for a time.

So how is it that mens hats, after playing such an active, evolving role on both cultural and political levels, seemed to virtually disappear from everyday society? There are a few facts, stats, and theories that come together to explain their gradual retreat from popularity. For one, the rise and evolution of the automobile. The four-wheeled engineering marvel would soon spell the beginning of the end for the gentleman’s hat, and its invention would soon alleviate the need to cover up one’s head for protection from the elements.

The Hat Research Foundation (HRF), which was apparently a real thing, also found that 19 % of men in 1947 who didn’t wear hats said it was because they triggered the trauma of war associated with their uniforms.

In fact, clothing companies kind of scrambled to revive hat wearing to its former glory after WWI and WWII. Ads sponsored by the HRF ran with slogans like, “You Need A Hat To Work Magic” while late 1940s newspapers mocked men rocking the new “barehead” fashion.

Traditional men’s hats retired to a place of ceremony and tradition with which we are familiar today. Many historians actually mark the day John F. Kennedy gave his inaugural speech as “the Day the Top Hat Died”. At first, the newly elected president participated in the age-old tradition wearing a top hat to the ceremony, walking arm-in-arm with a beaming Jackie…

It looks like he posed for some pictures in the hat, and then decided to shake things up by going top-less for the big speech. One would be hard pressed to find a starker visual metaphor for the changing times than that of the young president, literally backdropped by a sprinkling of older men in antiquated top hats. Welcome to the 1960s, baby!

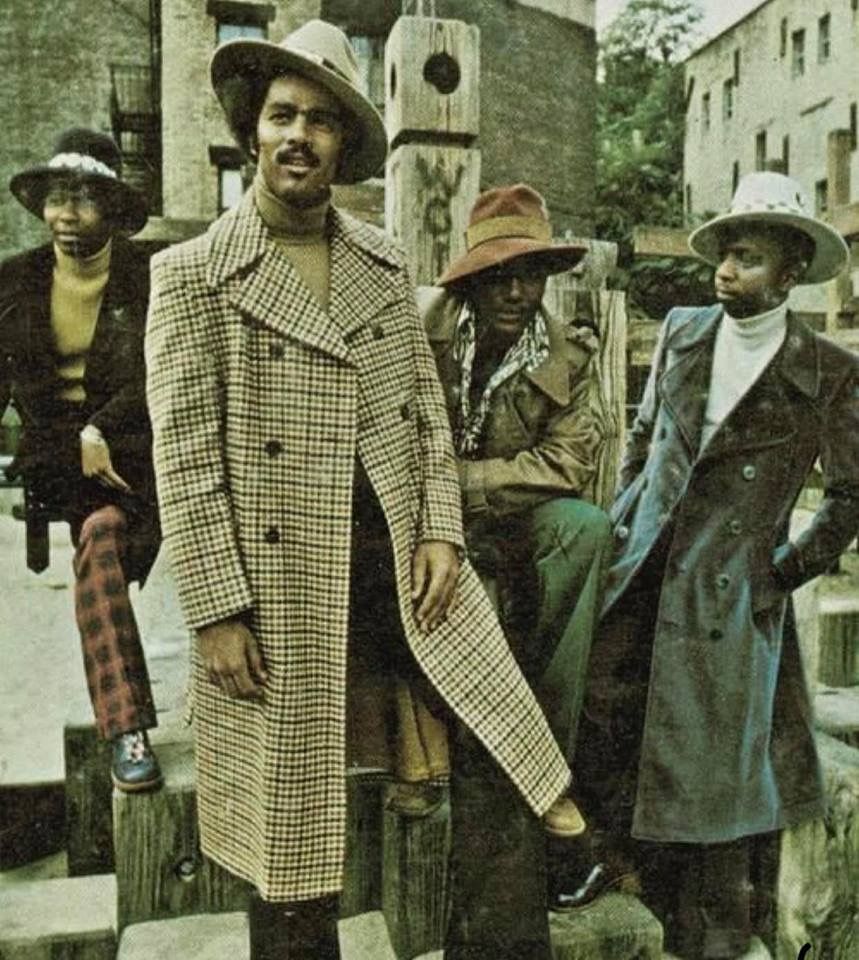

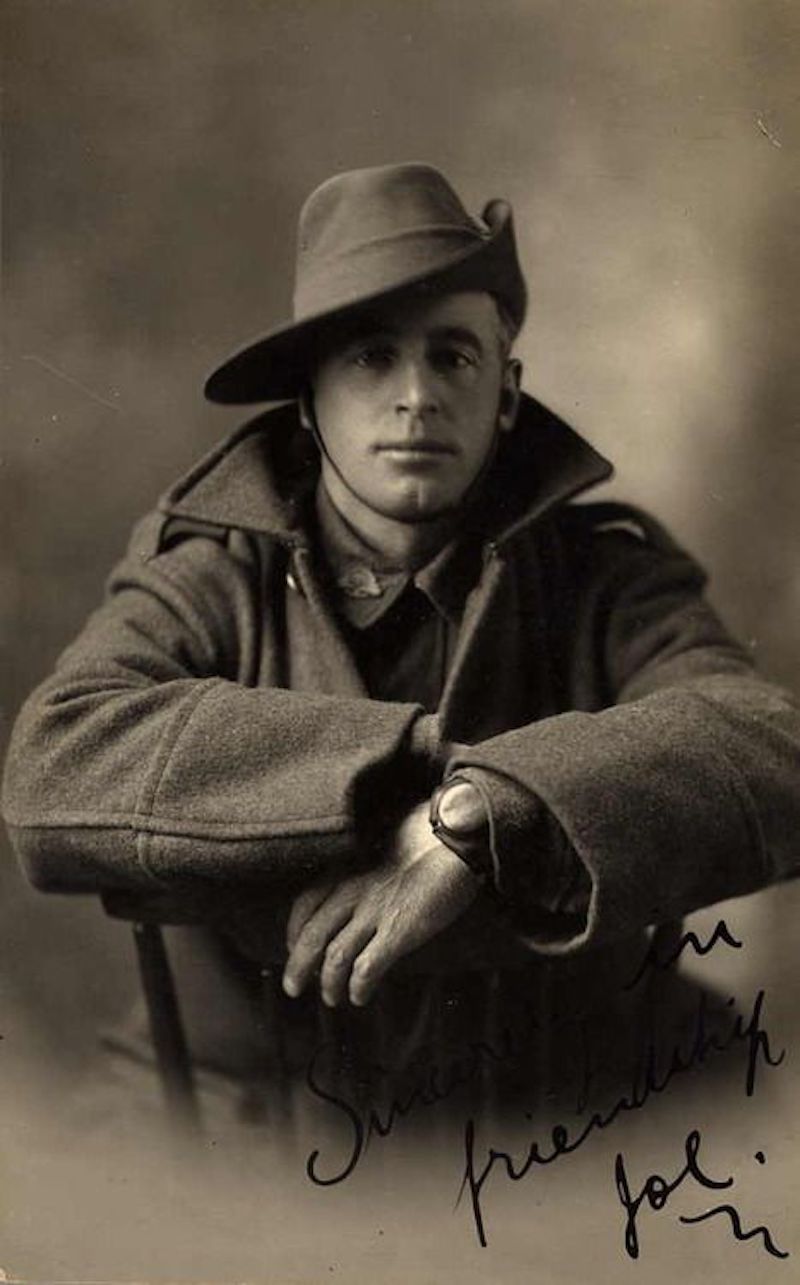

Every couple of years since, fashion journalists proclaim the hat’s comeback, but it seems unlikely we’ll see anything like those historical crowd scenes resembling an ocean of hats, ever again. These days, a swish hat on the streets feels perhaps less tied to old social codes and more so to individual or community expression. The shift is decisive: historically, men wore hats to fit in and today, men wear hats to stand out. Men in hats are still here, but we’d just love to see more of them, so we’ll leave you with some sartorial inspiration for the gents to pass around…

(It’s all about the angle).