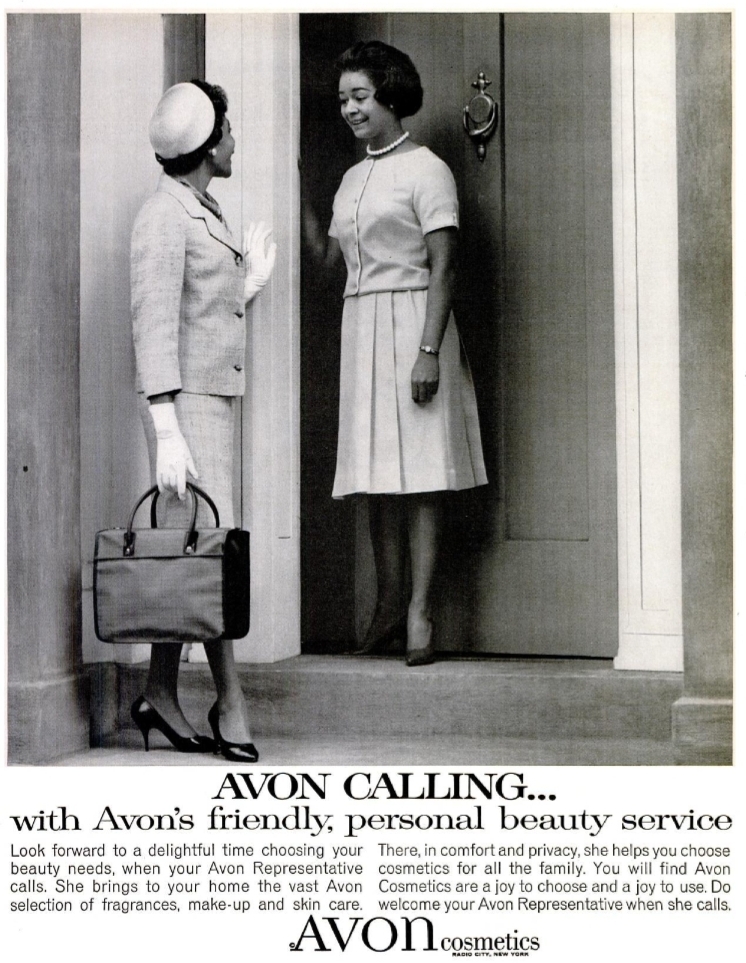

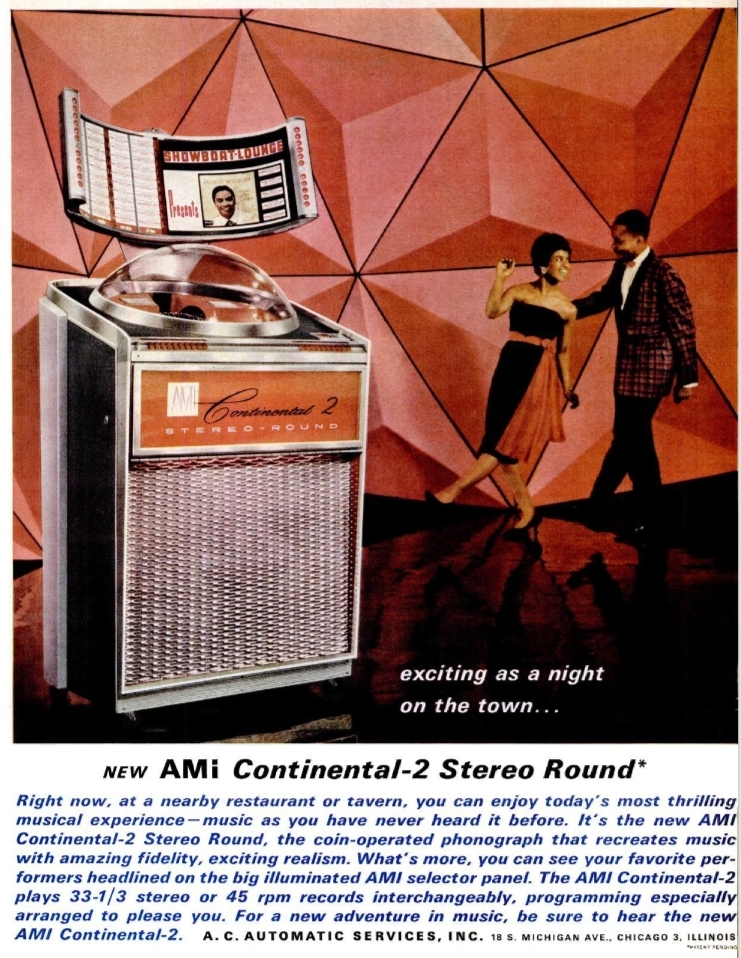

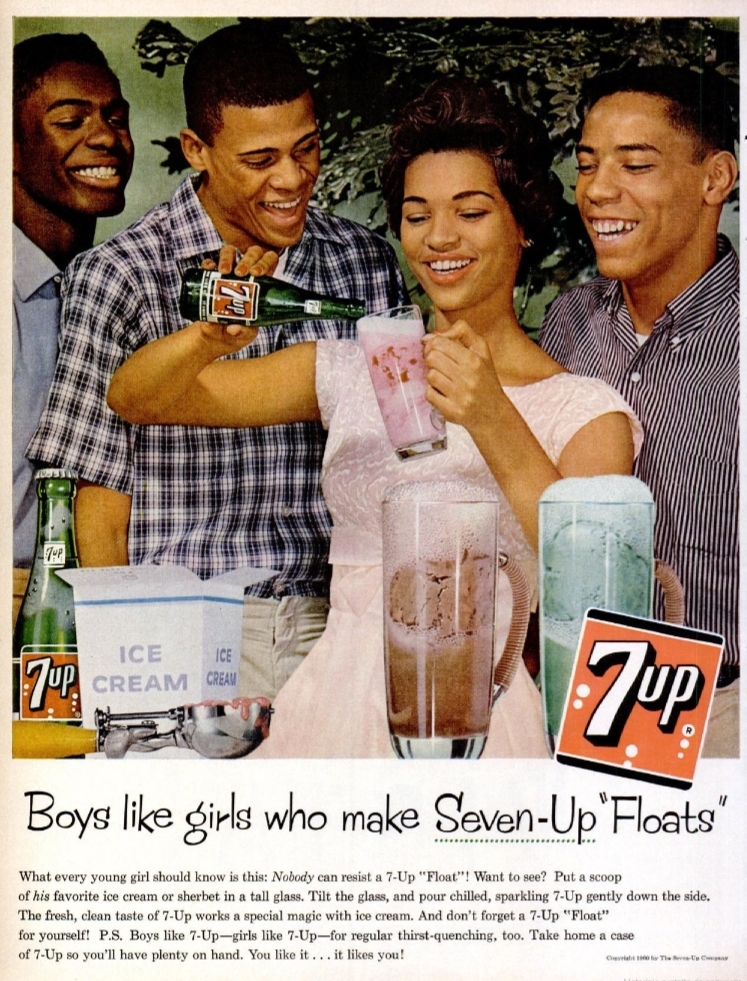

Style and smiles all-round, saturated to the max; sexy undertones complete with sexist overtones and carefree capitalism – those iconic mid-century advertisements weren’t just unique to the magazine pages of white America. In the 1950s and ’60s, the notorious advertisers of Madison Avenue, aka the real-life “Mad Men”, sought out African American dollars too. Unbeknownst to most, an entirely different realm of advertising hid in the shadows of mainstream society, directed towards a Black American class that was, and still is, rarely seen by white consumers. The adverts paint an unfamiliar, yet distinctly glossy picture of life for African Americans during those years. At once, it’s a joy to (re)discover this alternate world of Black media, but on closer inspection, the cracks start to reveal themselves beneath those smooth, vibrant, and wholesome images of Americana – cracks that have only become wider and more visible today.

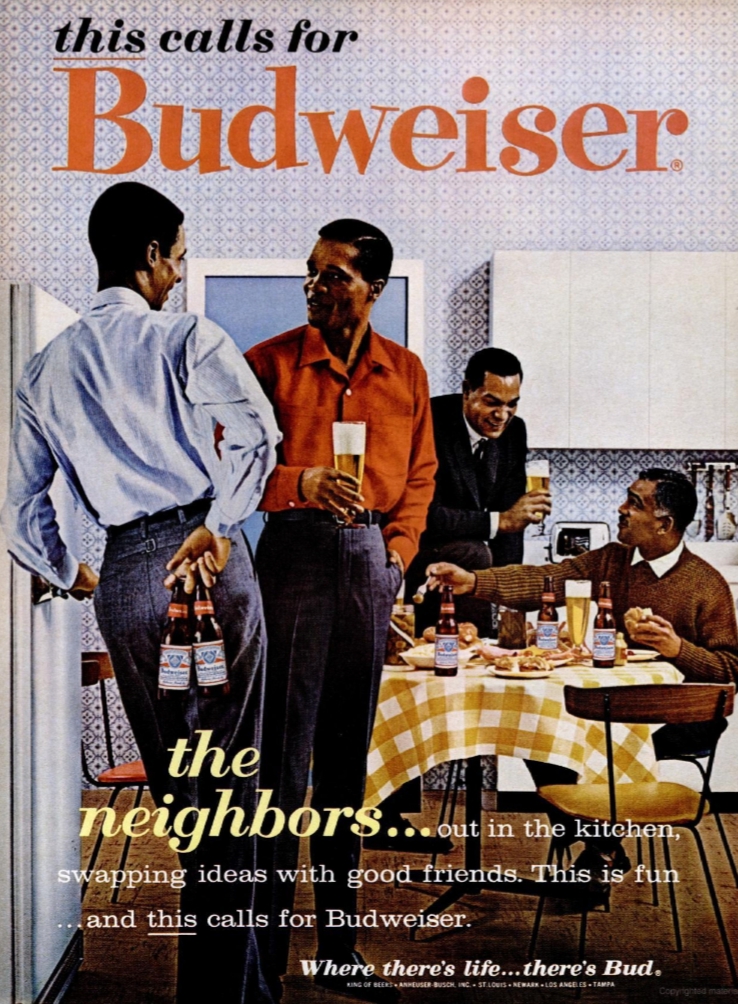

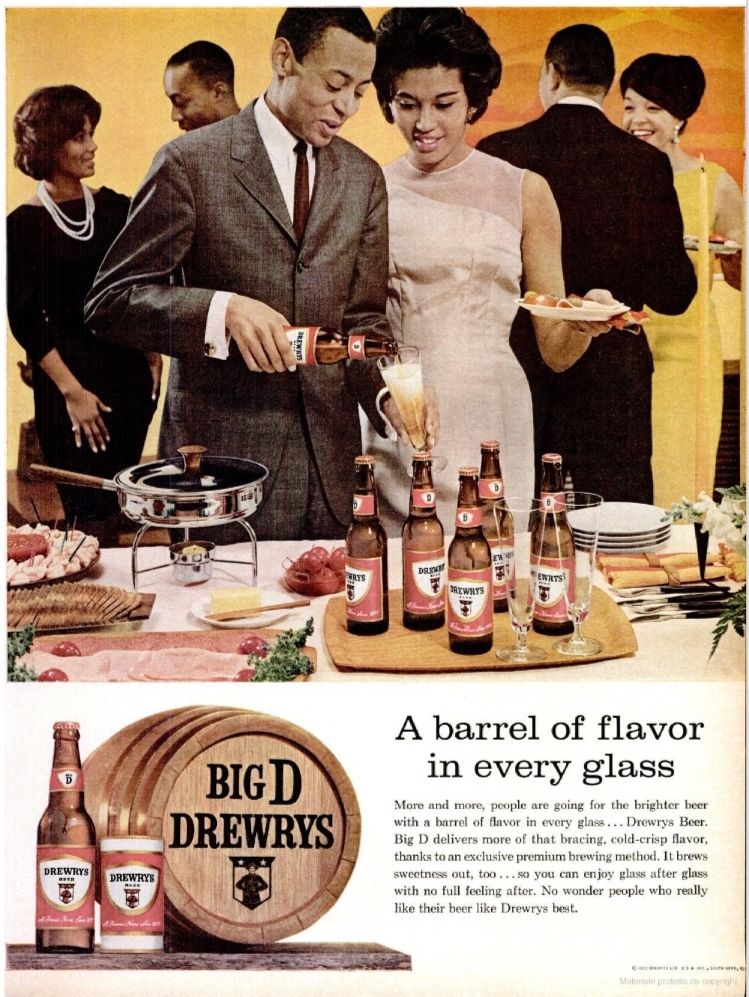

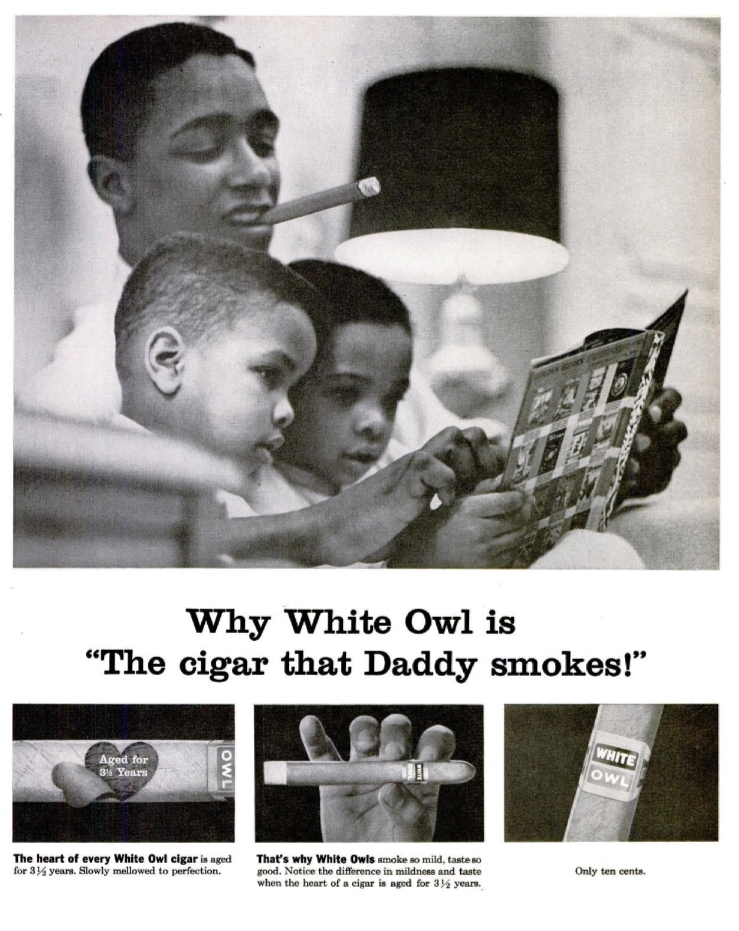

You won’t find ads like these in the archives of LIFE or Vogue or Esquire. You’d need to be looking in the few places where Black wealth was actually recognised and encouraged. Open up the archives of the Johnson Publishing dynasty, which produced magazines like Ebony and Jet, and suddenly, you’ll see the Black middle-class housewife elegantly smoking her Camel cigarette, Black businessmen loosening their ties over Budweisers and suburban African American families waterskiing with a pack of Pepsi on the weekend.

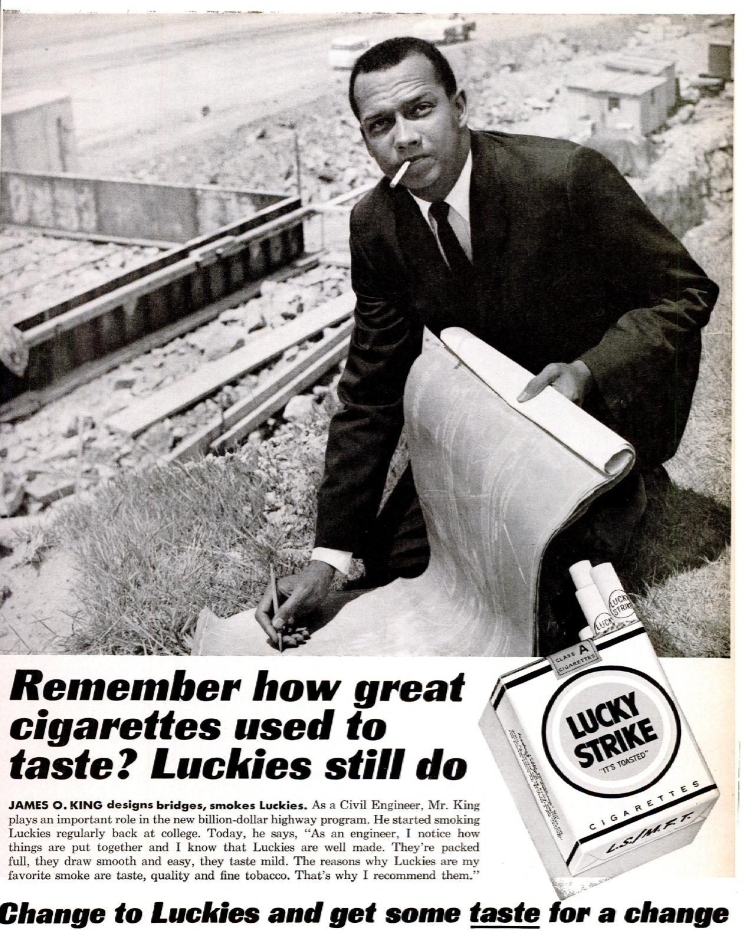

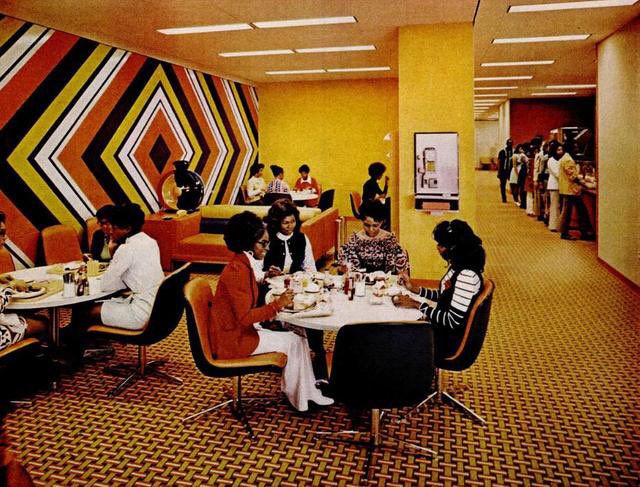

For decades, these revolutionary publications were the only place African Americans could find stories about their own community, portraying affluent Black members of society. Revelling in the African American dream, consumers could open an Ebony or Jet magazine at the hairdresser and see Black architects, lawyers and business-owners (even businesswomen) gracing the pages alongside advertisements featuring people of colour, selling a romantic, middle class lifestyle.

Recognising that the African American community was starved for such affirming imagery, founder John Harold Johnson saw the niche in publishing early on, calling the largely-ignored Black American consumer market a “black gold mine”.

Martin Luther King, Jr. once compared the treatment of Black Americans in everyday society and media to a “degenerating sense of ‘nobodiness’”. Before the Johnson Publishing Company came along, the Black consumer demographic simply didn’t exist to America’s corporations. But at its peak, Ebony, modelled on LIFE magazine, was circulating 2.5 million copies a month. Those kinds of numbers, said to be “unmatched by any other general-interest magazine in America”, couldn’t be ignored by corporations.

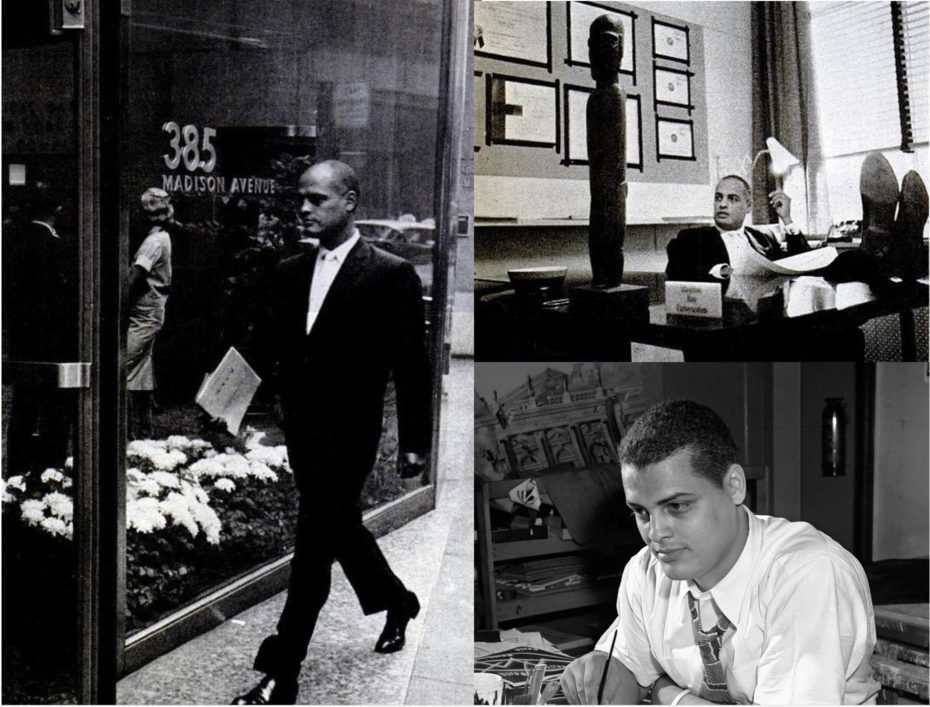

The Johnson Publishing Company, based out of Chicago, and a small pioneering group of Black marketing men in New York, convinced major brands that in order to reach the African American community, advertisements would need to speak directly to them, in their own lifestyle magazines, where their wealth, spending power and most importantly, their skin colour, was acknowledged and appreciated.

These ads would never be seen in the mainstream white media, but the marketing returns were nevertheless explosive for companies, giving rise to an invisible “golden age” for targeted Black advertising.

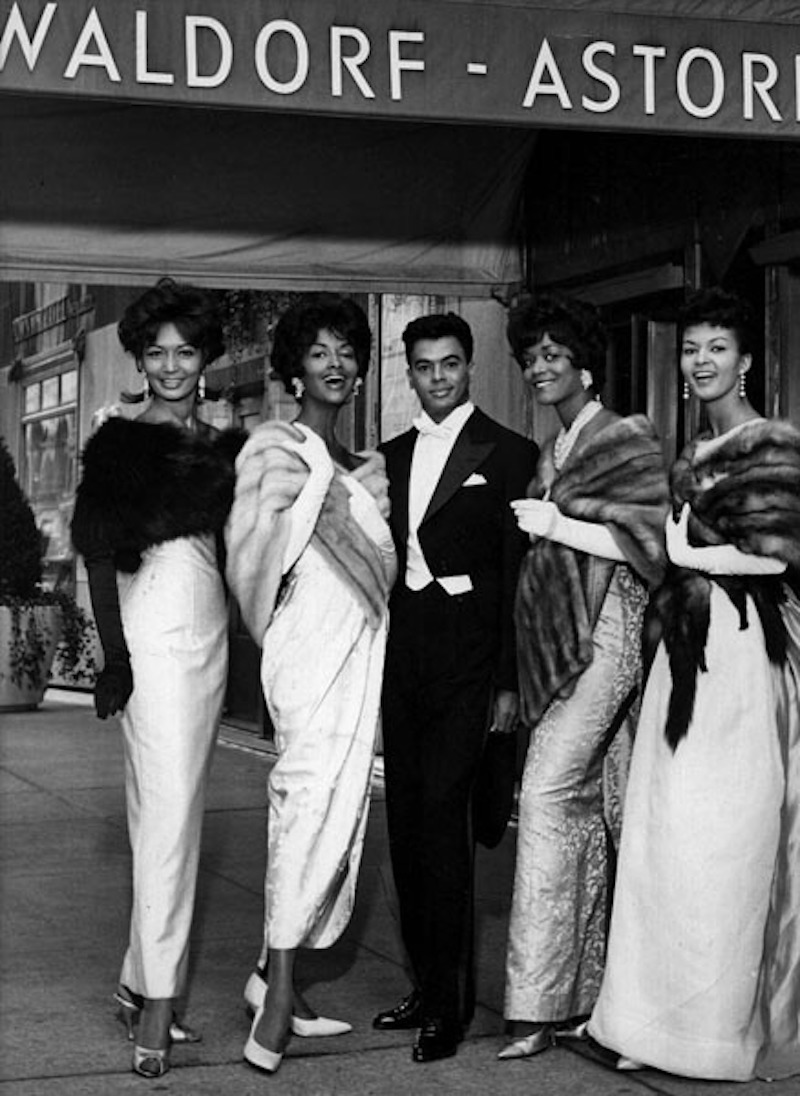

Ebony and its sister magazine, Jet, not only created work for Black journalists, but also Black-owned ad agencies headed by Don Draper-esque ad men, like the award winning Georg Olden (above) and Vince Culllers, who founded his own advertising firm, and became one of the leaders of the Black advertising agency sector in the 60s and ’70s.

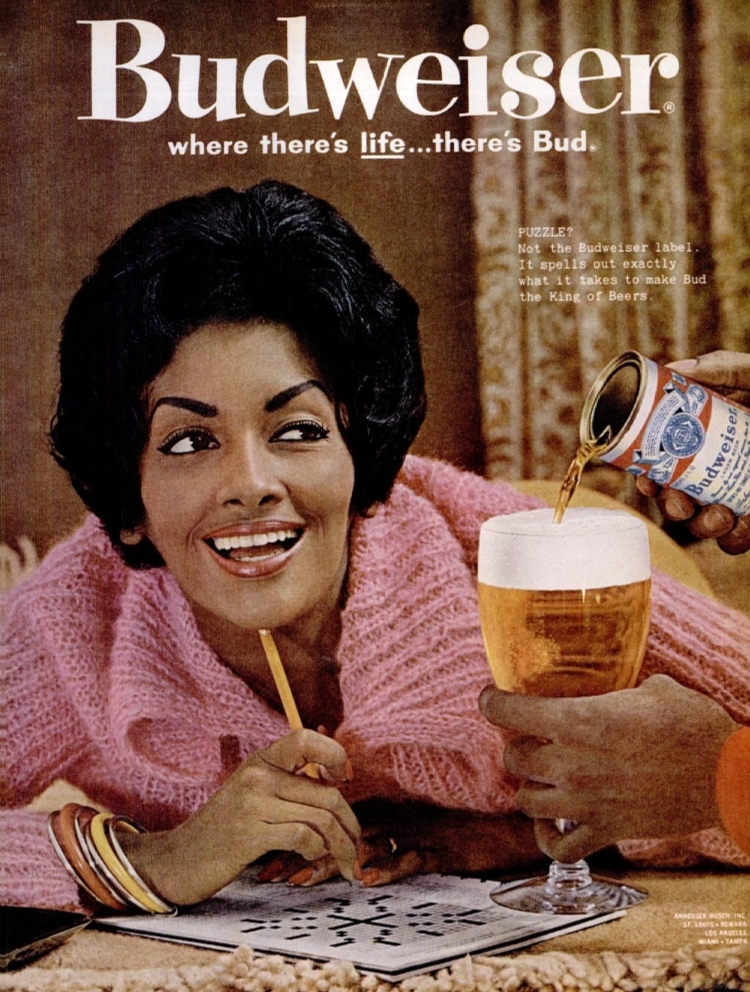

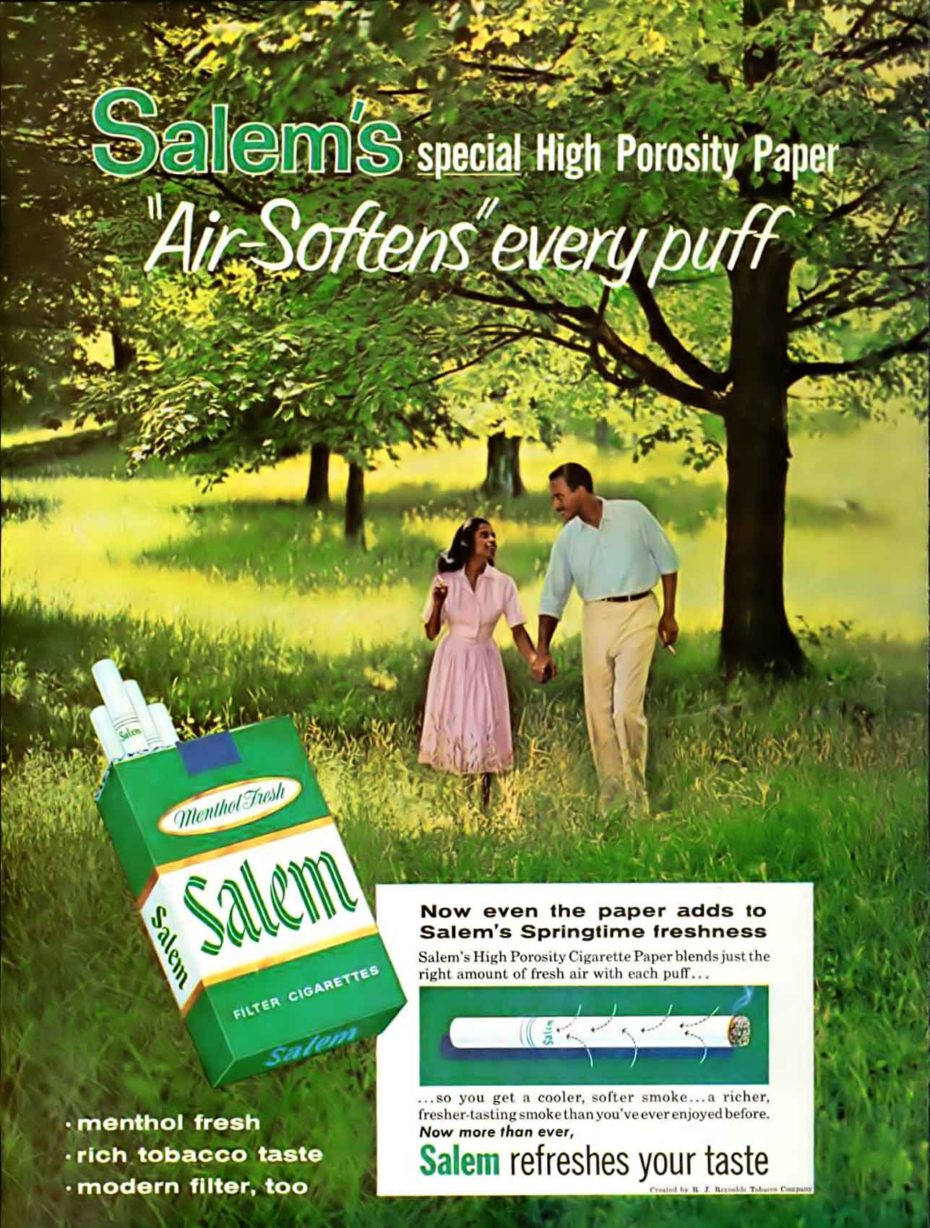

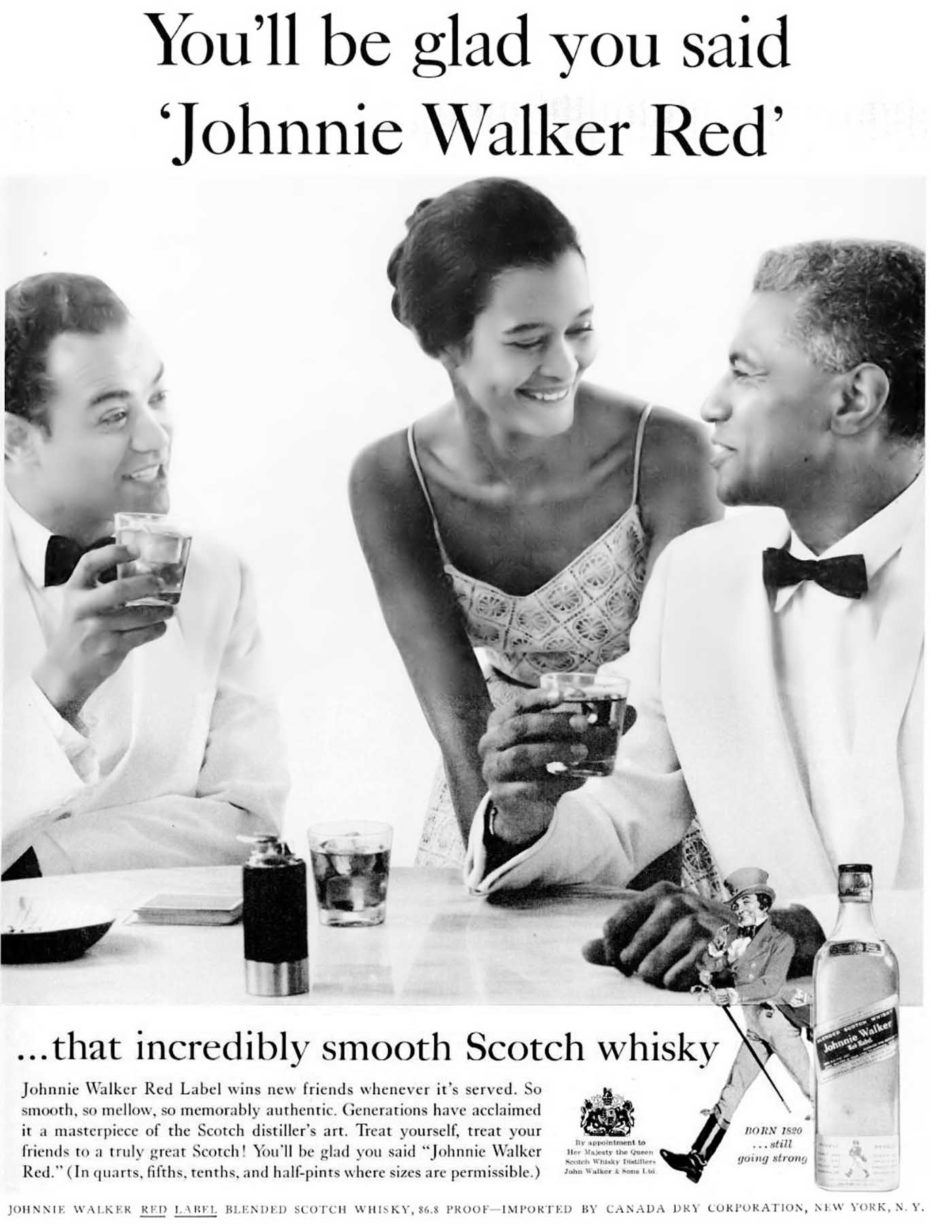

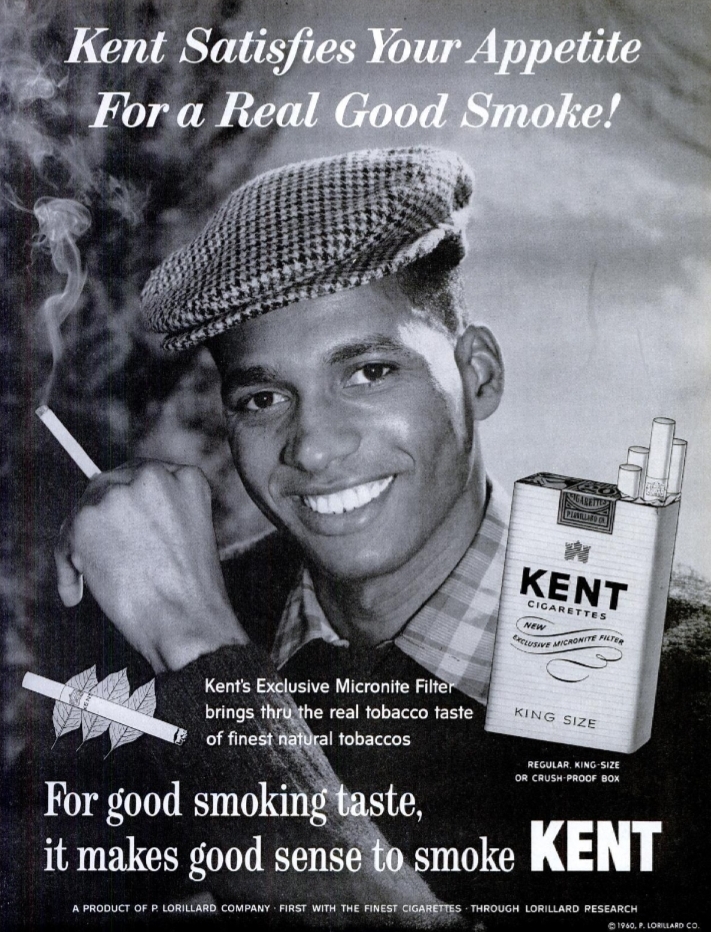

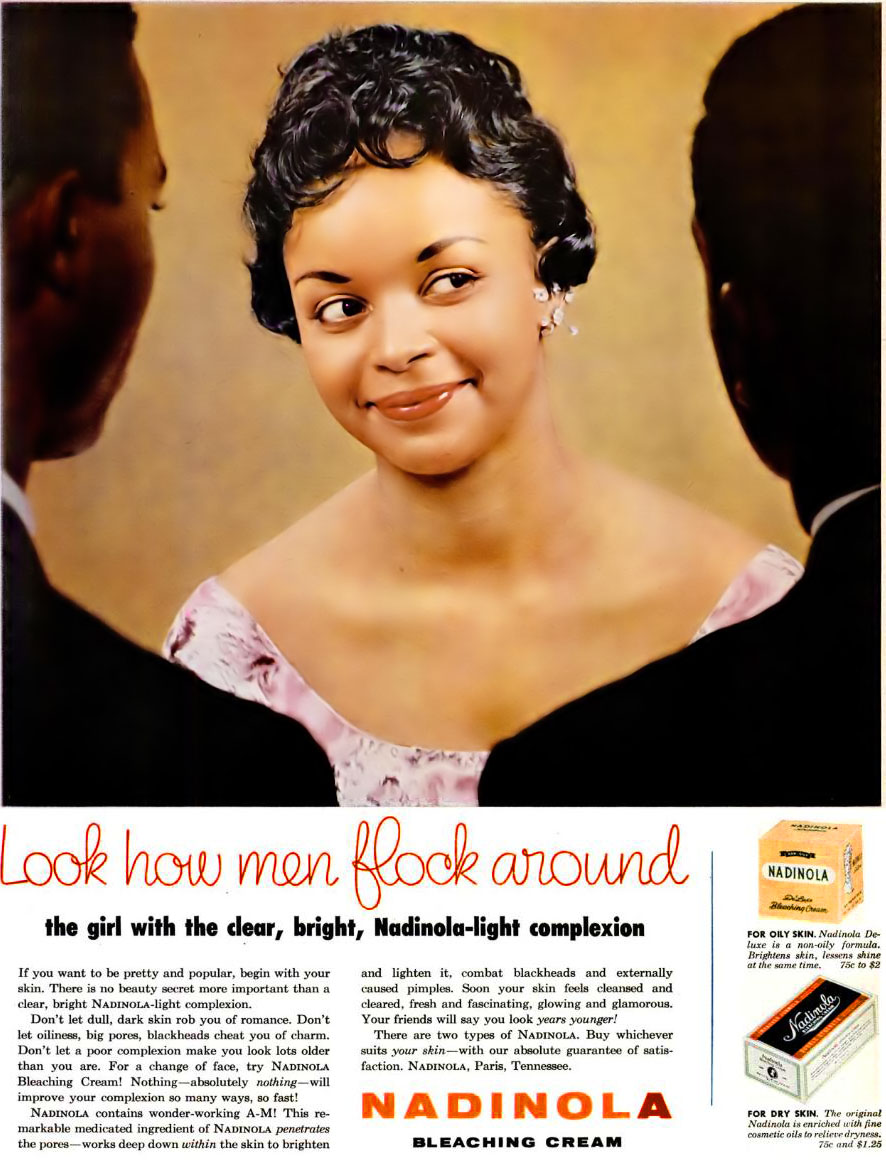

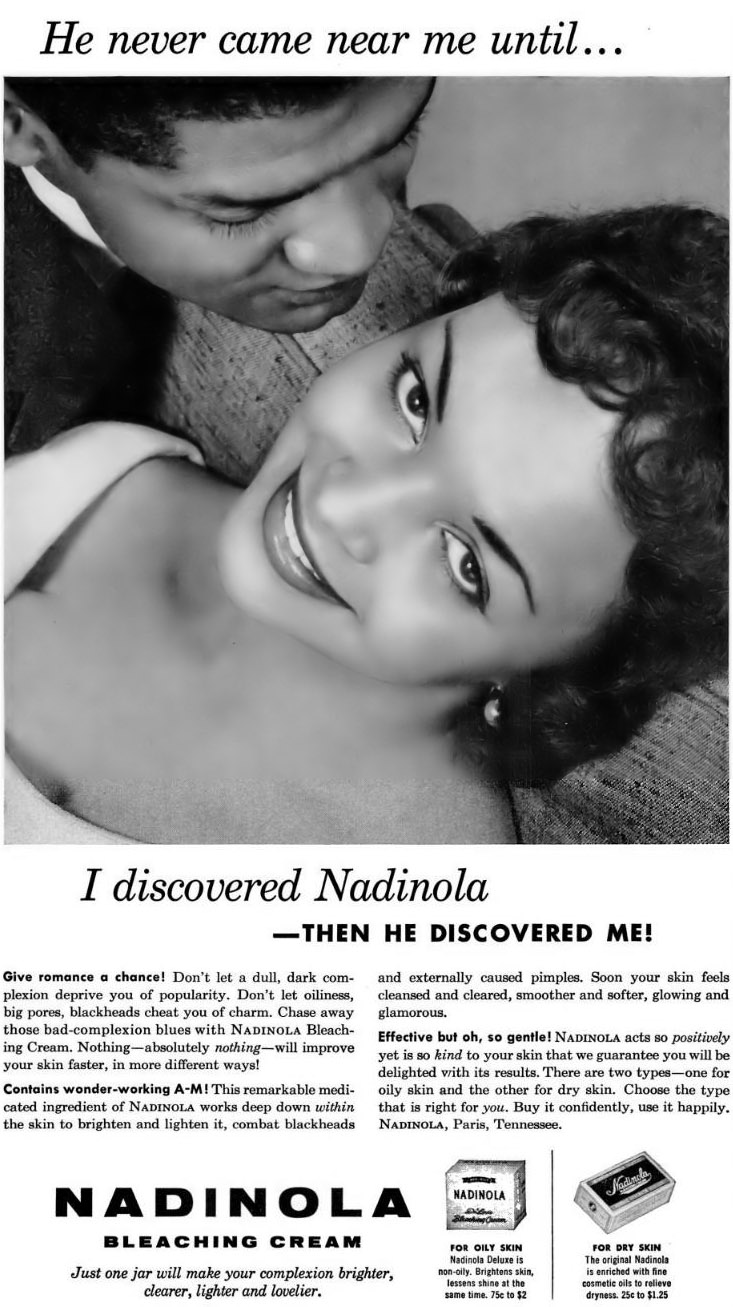

Cigarette companies were among the first to work with Black publications, and once the barriers were reluctantly broken, tobacco giants began aggressively targeting Black Americans (who were generally smoking less than white Americans at the time). Alcohol, beverage, cosmetics and automobile brands – the usual suspects – soon followed suit. But across the board, advertisements were generally a cut-n-paste job, meaning, that the ads placed in Ebony and Jet were often created as white-targeted campaigns, given no special creative attention other than replacing white faces with black ones.

Very often, the copy was exactly the same as it was for the white consumers, and all too often sounded tone deaf to a Black audience. Jason Chambers, author of Madison Avenue and the Color Line: African Americans in the Advertising Industry notes that “many of the ads done by mainstream agencies approached Black consumers as if they wanted to be white.”

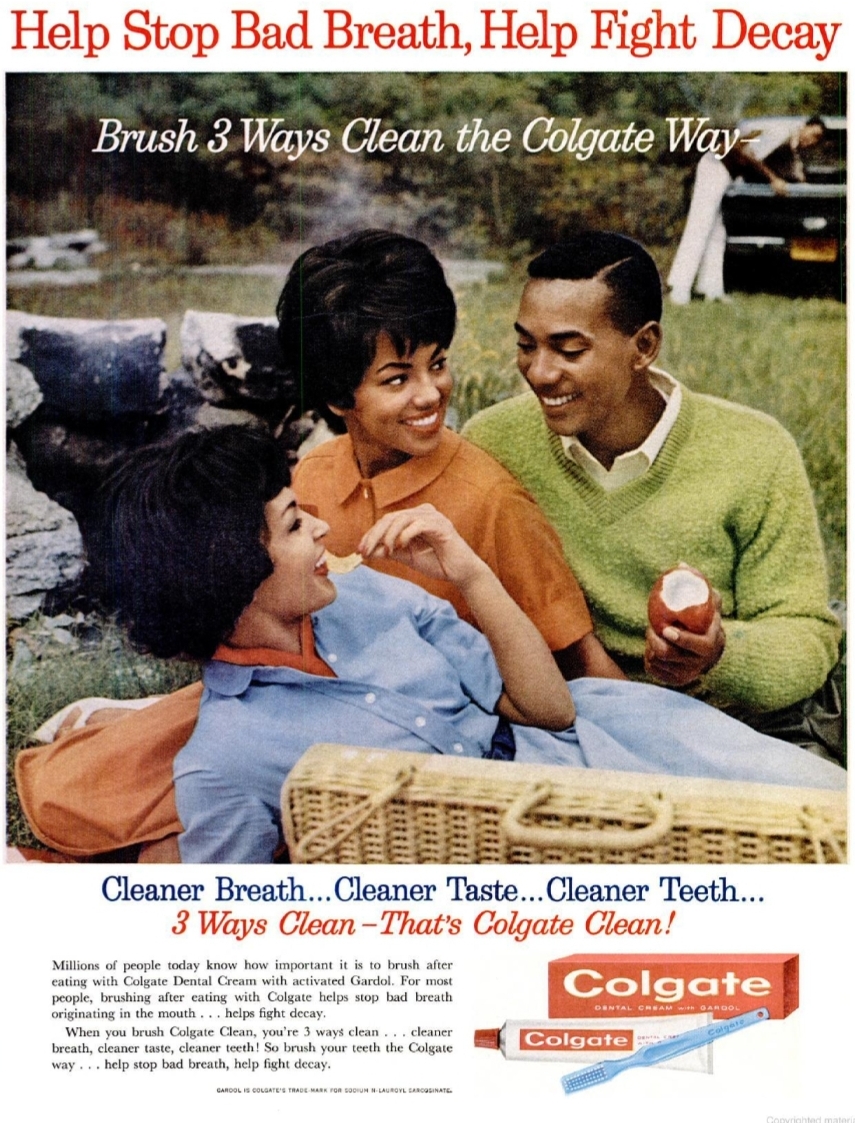

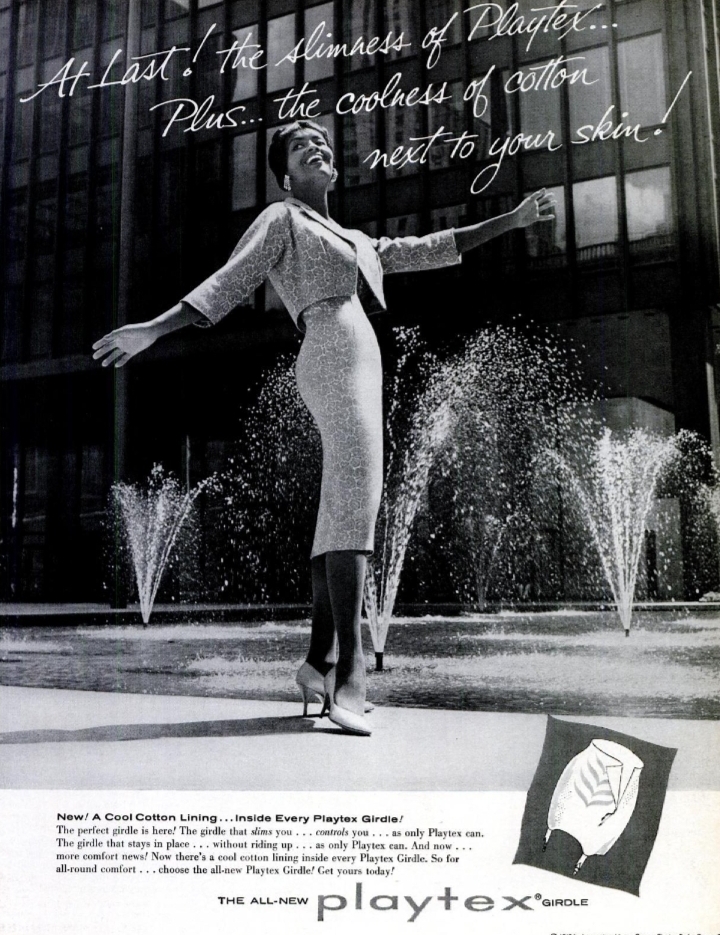

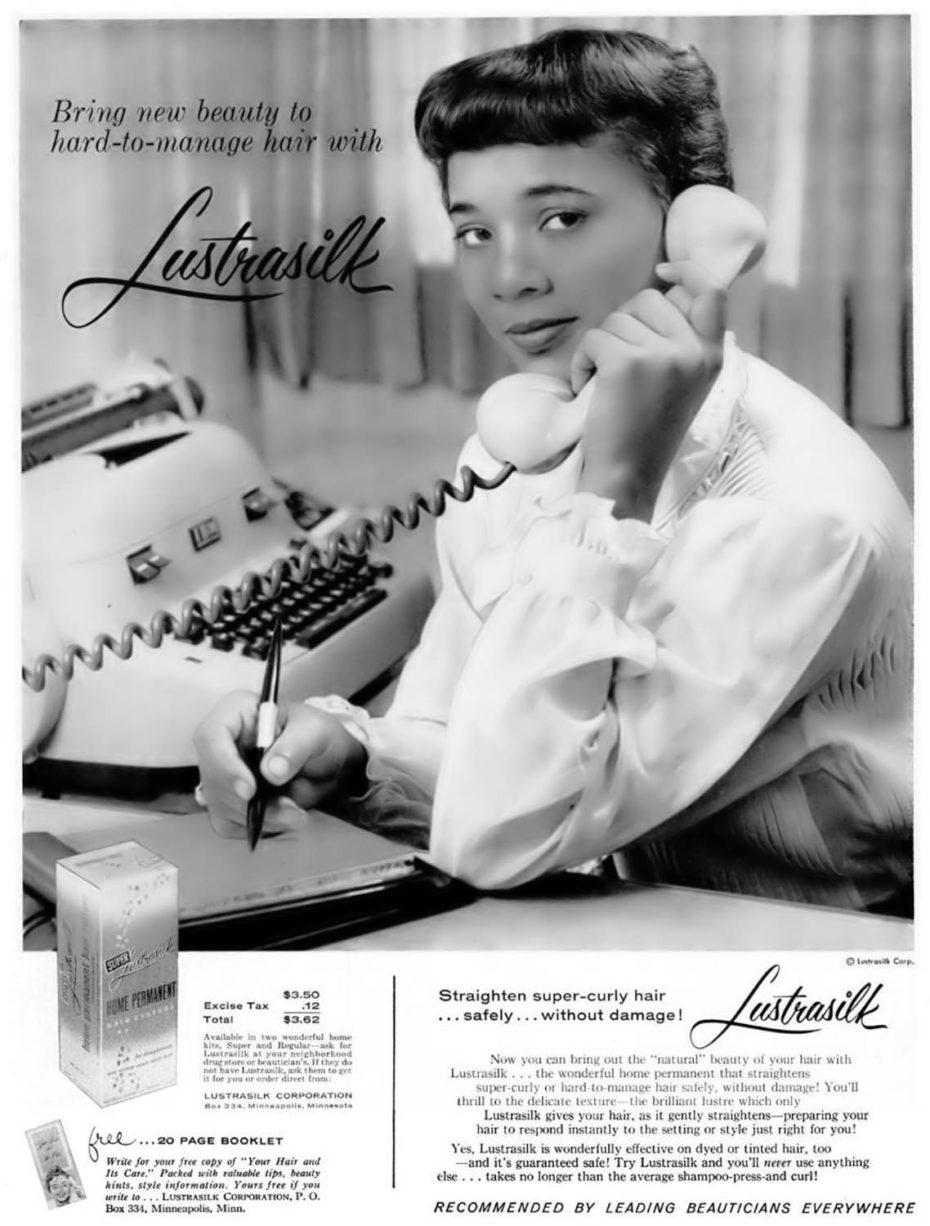

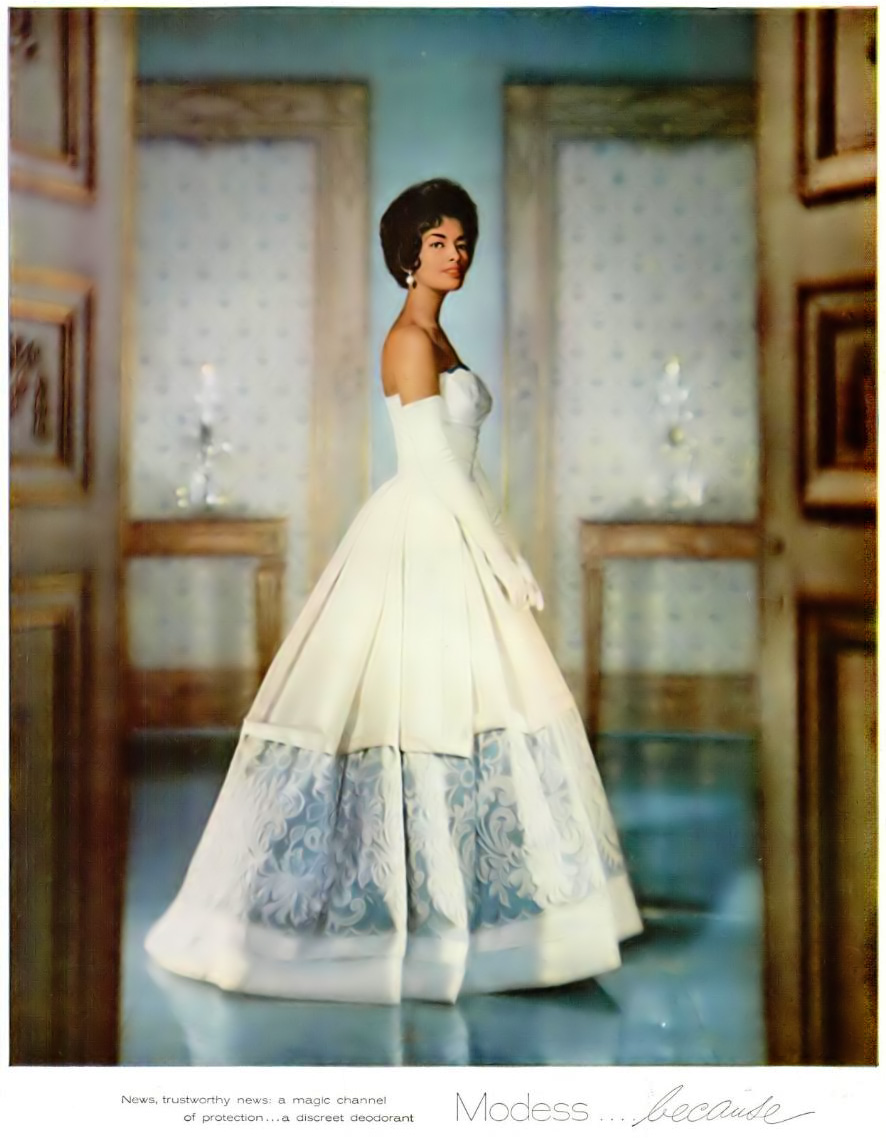

Edward Brandford co-founded the first modelling agency for African American women in America, and helped create the “Brandford look”: slender, with medium skin tone and height, and long or straight hair. Models were frequently styled to look like the ideal American Stepford housewife, an aesthetic that of course, required changing and “taming” a Black woman’s natural beauty.

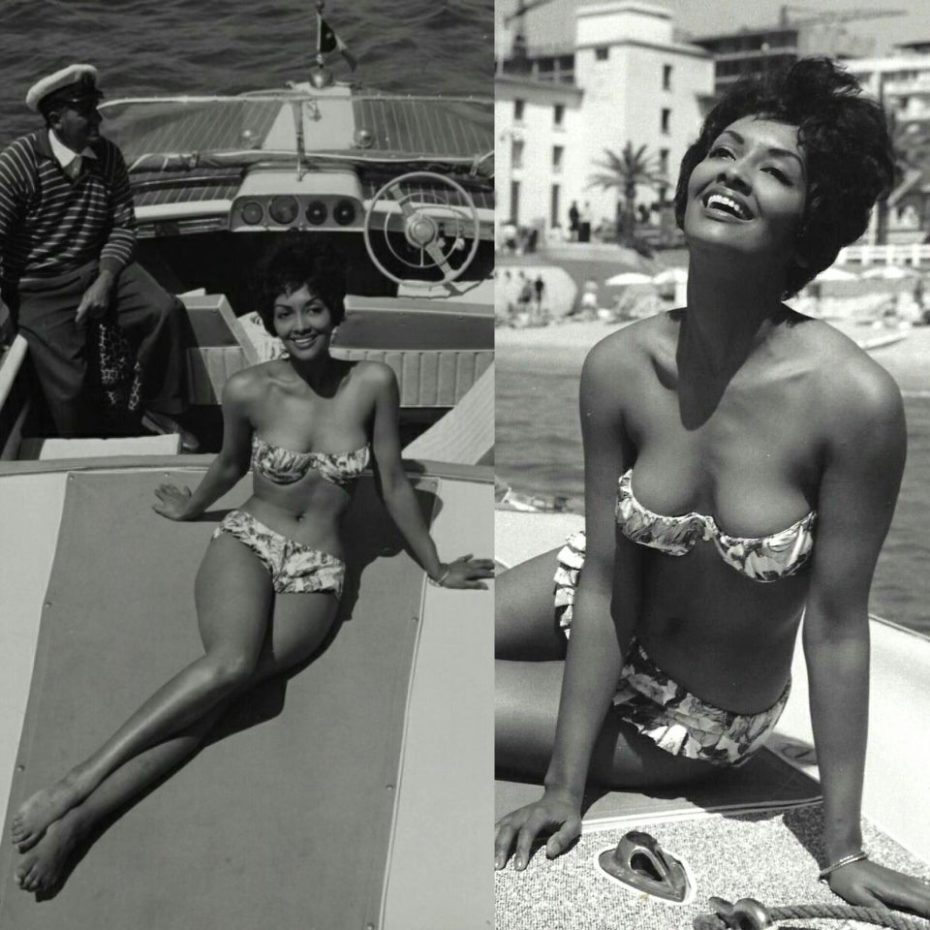

No other model embodied the “Brandford look” quite like Helen Williams, whose striking face you’ve already seen several times by now in this article. She was one of the most familiar faces in Black advertising in the 1950s.

Discovered while working as a stylist in New York City, she became one of the most successful models in American retail advertising and worked overseas for Parisian fashion houses including Dior, paving the way for dark-skinned women in the fashion industry.

Still, having dark skin, Helen faced constant discrimination at every turn in the American industry, particularly early on in her career. “I was too dark to be accepted,” she recalled. Having never written an autobiography, it’s uncertain whether Williams might have encountered the odious practice known as the “brown paper bag test” during castings. Used openly until the 1950s, amongst upper class Black American societies such as sororities, fraternities, even churches, and possibly in a small but highly competitive Black modelling industry, only those with a skin colour that matched or was lighter than a brown paper bag would be allowed admission, membership privileges, or get hired for certain jobs.

The grim practice of colorism-discrimination is thought to have originated in Louisiana’s Creole community at the turn of the century, where mixed-race children of white slave-owning fathers were sometimes given privileges ranging from more desirable work in the field to eventual freedom from enslavement. Once freed, some attempted to distance themselves from slavery and rise out of poverty, placing value on their lighter skin complexions, using it to their advantage in white society, and preferring to associate themselves more closely with their French European ancestry.

The fetishizing of lighter-skinned women is sadly still prevalent, but most noticeably detected in the archives of Ebony, Jet and other mid-century publications…

While the Johnson Publishing Company dynasty was revolutionary for its depiction of middle-class African American life, it often came under attack for embracing white standards of beauty and frequently running advertisements selling skin lightening creams. Such cosmetic products are still coveted in certain African and Caribbean countries where the image of the sophisticated Black man or Black woman is often held as being in opposition to dark skin.

The Civil Rights protests of the ’60s finally forced advertisers and agencies to change their approach and diversify. Art director Vince Culllers, had grown frustrated creatively during his years working for Ebony in the early 1950s and sought to reform the ways in which advertisements were portraying Blacks in the industry. In doing so, he created the first Black-owned advertising agency in 1956.

“Advertisers and agencies needed to adjust to the new sense of pride that Blacks felt or face sales repercussions,” writes Professor Jason Chambers in his book examining the industry, “… to whites, consumption of a particular product was as an indication of Blacks’ desire to be white, but to Blacks it simply demonstrated their desire to be middle class.”

In the words of another pioneering African American ad man, Leonard Evans, supposedly articulated to a white marketing manager during a pitch meeeting on Madison Avenue:

“We [Black people] have no great desire to become white. In fact, we tend to have more pride than ever in being negroes. Integration does not mean the elimination of Negro culture.”

More than half a century later, does it feel like today’s brands and corporations got the memo?

Archive advertisements found on Flickr.