It’s a weird time to be a consumer. Emerging from lockdown, folks around the world are gauging the risks of doing something as seemingly simple as stepping outside, let alone step inside a shopping mall – an aspect of American culture in particular that is entering a new era. On the hand, we can look to malls as the place where so many of us went as teens to feel a little independence. On the other, these massive centres of commerce host harmful fast fashion companies, and an increasingly disappearing business. Even before covid-19, many iconic retailers were shuttering, which now begs the question: what is the fate of the mall post-pandemic? How can we adapt these spaces for the future?

The mall is such an American institution, that it’s become it’s become on-screen shorthand to confirm that, yes, you are probably watching a coming-of-age movie or TV series. Is there a more iconic line for millennials than, “Get in, loser. We’re going shopping”? From Mean Girls (2004) to Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982); TV shows like Degrassi, Saved by the Bell, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and so many others, the mall was an ever buzzing hive of interaction.

Think about it. Outside of bars, where else would you find as many social opportunities that, now, unfold with such prevalence on social media platforms? Remember that iconic scene in Fresh Prince when Will and Carlton go to the mall to find a date before midnight?

These days, we flirt on Tinder, promote music on Myspace, and rely on Facebook to wish family members happy birthday. Not exclusively, of course, but their cultural pervasiveness is undeniable and ever-increasing during the pandemic. Remember all those Zoom happy hours in lockdown? The late nights spent ordering things we don’t need online? Ah, what we would’ve given to stop into the shiny mall of our youth for a soft pretzel, maybe a new ear piercing…

Not to mention, the mall architecture. Seriously! Love it or hate it, you can’t deny the nostalgic power of the pique mall era’s faux-chrome surfaces, and random architectural follies, most of which were informed by the 1980s Memphis Group design values (think squiggles, shapes, neon). The fountains! The unnecessary bridges! The massive crocodile statues! For all of its camp, malls were always intended to provide a landscape outside the norm…

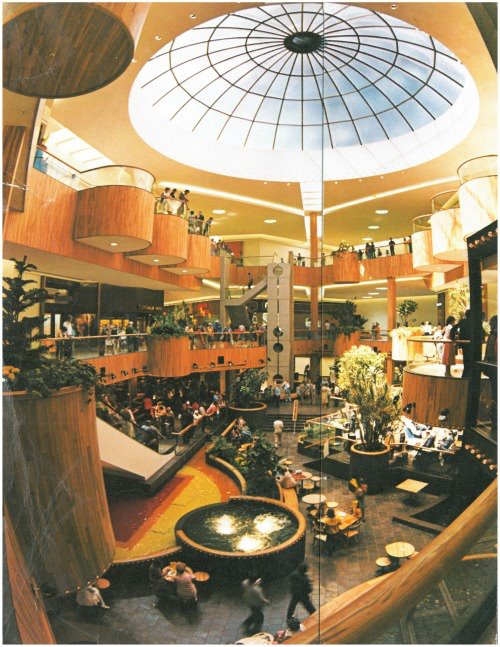

Impressive mall waterworks, for example, really hit their stride in the 1970s. Coincidentally, around the same time that intense indoor gardens started trending.

Eventually, the world even got ‘tropical’ waterslides at malls…

Some pretty amazing talents have also drawn up plans for malls, from author Sci-Fi Ray Bradbury, to the artsy duo behind “BEST,” a chain of US retail stores founded by husband and wife Sydney and Frances Lewis, who were collectors of 20th century art. In the mid-1970s, they contracted American architect James Wines, the founder of “SITE” (Sculpture in the Environment) to give nine of their retail stores an avant-garde make-over that would reflect their own artistic sensibilities. We’ve written a whole article about it.

These days, malls and national chain retailers are closing left and right. It feels like hoidy toidy department stores, those once revered temples of the all-day shopping experience, no longer speak to the need for a more sustainable, personable, and accessible shopping experience. An article published just last week in Bloomberg reported that particularly in light of America’s economic fallout and spotty management of covid-19, that “brands such as Cheesecake Factory and the Gap are skipping rent payments, Starbucks is closing physical locations, and developers see a future for big box stores as office complexes.” So how did we get here?

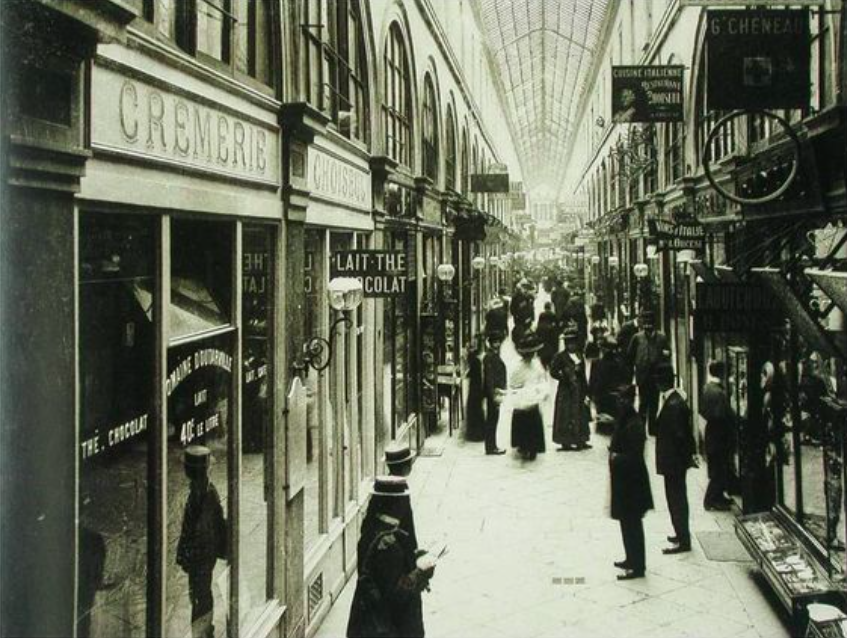

Let’s go back a little further in mall history. Lest we should forget, Middle Eastern countries have always been doing a version of the mall; Westerners just rebranded the concept of the “bazaar” to suit the European lexicon. In 1798, the first European arcade was built in Paris, France in the 2e arrondissement’s Passage du Caire, and was followed by the construction of some 150 covered passages in the city.

In the United States, the “The Westminster Arcade” was built in 1828, in Rhode Island, as the first enclosed shopping mall in the country. These days, it’s a blend of swish lofts and select retail spaces. Check it out.

But the American mall as we know it today was a byproduct of many things, namely the rise of the automobile, the middle class, and the post-WWII dream of the Nuclear Family living out its days in the suburbs. Prior to those changes, shopping meant heading to your town’s main drag, or (if you could foot the bill) department store. Suburban expansion, however, created a need for a one-stop-shop. The first enclosed mall, the “Southdale Regional Shopping Center” was built in Minneapolis in 1956.

When we talk about the mall as byproduct of suburban development, it’s important to remember that those developments did not create an inclusive space for non-white buyers. Until 1948, it was perfectly legal to restrict race on property deeds. Until 1968, race was a legal excuse for banks that denied financing. Malls were a futuristic daydream of Googie architecture, massive grocery stores, and automobile showcases, and access to those developments for communities of color was not the same. The New York Public Library has an excellent article on the complexities of housing justice and African American suburban development, for example – we highly recommend you to read it.

Another thing we weren’t taught in school? That the American mall was pioneered by a Jewish immigrant fleeing the Nazi takeover in his native Austria, Viktor David Grünbaum. He found shelter and a new life in the US as “Viktor Gruen,” arriving in New York City with only his degree, eight dollars, and no command of English. He was known a man of charisma, a “torrential talker with eyes as bright as mica and a mind as fast as mercury,” according to Fortune magazine’s profile, and soon established a “Refugee Artists Group.”

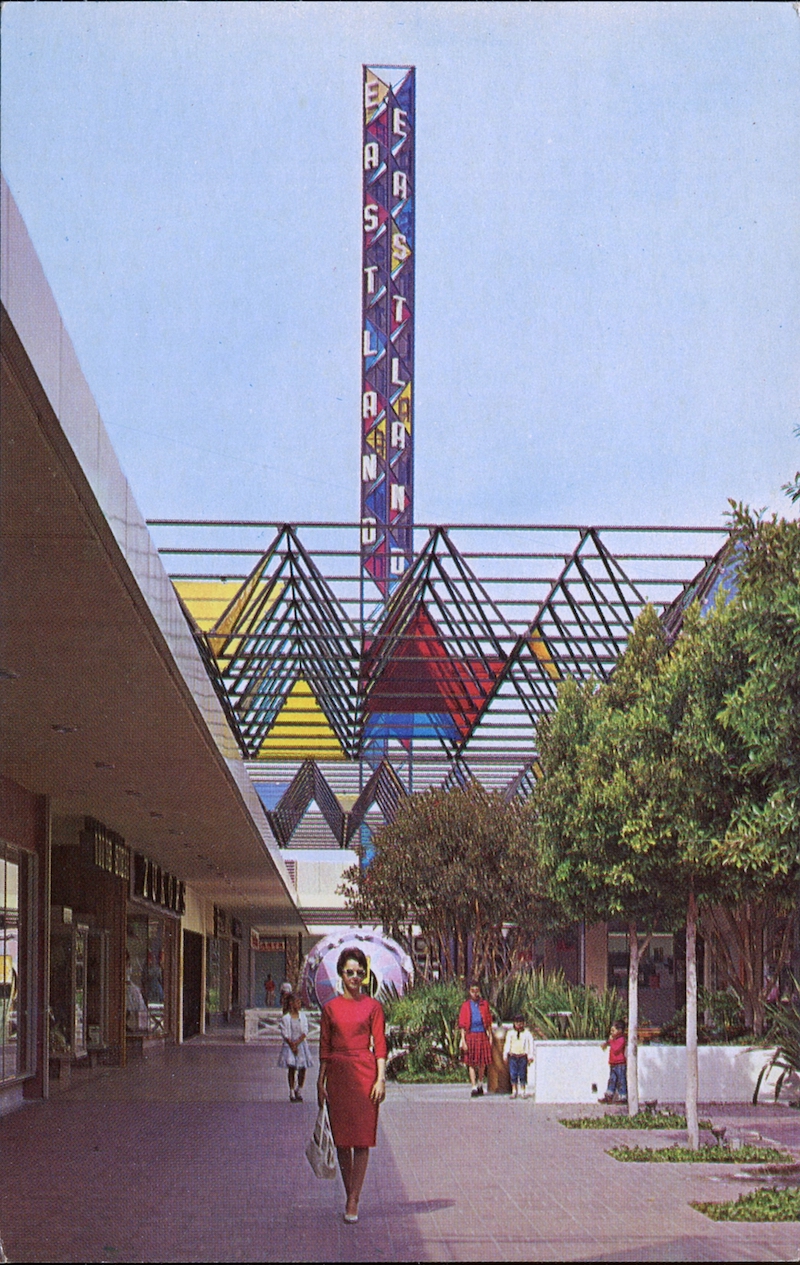

As important as cars were to the mall, Viktor believed in “prioritising pedestrians over cars” in urban community spaces, and also built the first outside pedestrian mall in the US. Under his stewardship, the era of the mall as a spectacle and experience for the whole family, rather than mere pit-stop, was underway…

Then came the arrival of the “anchor store,” aka a large department store like Sears (remember them? You could mail order an entire house from their catalogue), also became a mall staple. Specialty stores and boutiques for men, women, babies, pets and everyone in between also flanked their premises. As far as entertainment goes, what began with humble midcentury “visits from Santa Claus” blossomed into spaces for local talents to perform. If you ask us, the late 1970s is when malls really started to get fun…

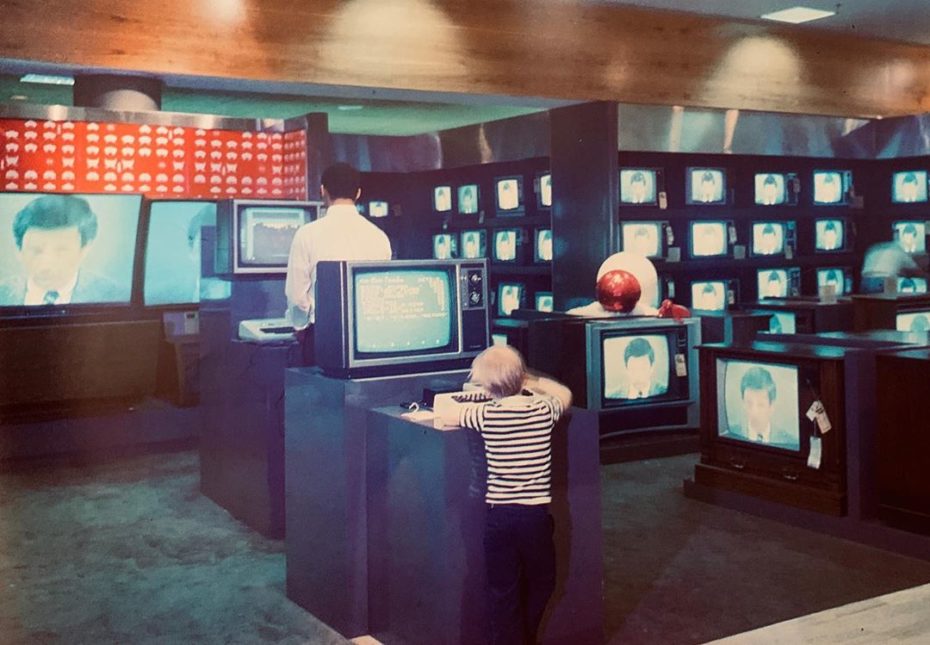

Once the 1980s rolled around, the mall aesthetic we’re so nostalgic for today reached its neon-lit pique, serving up Back to the Future-worthy facades, space age stores filled with Ataris, totally radical settings that backdropped your first date…

Shoutout to this 1980s Alabama mall foyer known as “Parisian Plaza”:

In a funny twist of fate, the concept of the massive, modern American mall was adopted elsewhere in the world. Paris, for example, is home to its own malls, from the newly revamped Les Halles commercial centre, which has gotten quite an American facelift, to the near derelict mall hiding in plain sight by the Louvre. The near total abandon of the latter occurred in the 2010s, save for one staunch shopkeeper named Martine, and was a rather prophetic reality. A dramatic warning that large scale brick and mortar stores might be phasing out…

The pandemic only accelerated that decline. US malls have been in decline since the early 2000s, when the internet opened up a whole new world of both more affordable shopping and social experiences that has only gotten more sophisticated, and more interwoven. Their ’00s decline was a warning, followed by the fall of big anchor (ex. Sears) and luxury stores (Barneys New York) in the 2010s. One of the biggest hits yet was Manhattan’s $25 billion Hudson Yards development, which opened last year and just lost its anchor store, Neiman Marcus, to bankruptcy.

©Stephen Pham / Flickr

“Before the Great Recession we had too many retail spaces; now we have way too many retail spaces,” reported Bloomberg recently, “The outdoor lifestyle centers will survive — they’re perceived as safer than indoors. But it’s hard to escape the fact that we’ve trained people to fear the world, and that it’s going to have long-term impacts on their behaviors.”

It’s an equally thrilling and risky time to be a small business owner, on the other hand. The potential to foster digital reach and support is incredible, and if there was any business that could more easily adapt to the no brick-n-mortar model, it just might be them. “Once-mighty brands such as Cheesecake Factory and the Gap are skipping rent payments,” says Bloomberg, “Starbucks is closing physical locations.”

Is this “retail apocalypse” a global trend? Some shopping malls are still doing okay in Europe. In France, the chain “FNAC” harkens back to the the glory days “Borders,” a long-gone music and book retailer. In Russia and various Asian countries, the Western inspired mega-mall is an increasingly popular novelty. In America, the health of these retro watering holes continues to vary. More than half, Bloomberg predicts, will be gone by 2021.

Yet, that same investigation into mall health finds an intriguing silver lining. One that envisions these empty monoliths as ready(ish) spaces for housing, peppered with local businesses. “Such transformation,” Bloomberg says about a mall-to-residency effort being proposed at a mall near Seattle, “could even bring malls closer to the ‘village square’ concept they were initially envisioned to become.” According to a senior attorney at the Pacific Legal Foundation, a specialist in such logistics, “the conversions are simple” minus a few zoning regulations and commercial conversions. People are craving more walkable developments with closer resources and amenities, rather than sprawling space.. The integration of offices and mom ‘n pop shops would fulfil that need, whilst solving issues of housing shortages.

As we continue to recalibrate what it means to be not only a better consumer, but a better neighbour in the time of covid-19, we can’t think of a better initiative – to make the mall a place that prioritises not materialism, but people.