Who doesn’t love a good B-movie monster? Step into the world of tokusatsu (特撮), or “special effect filming” in Japanese. The term is shorthand for a genre of live action films bursting with heavy handed special effects, and a slew of freaky, giant creatures known as kaiju (monsters). Some top notch cheese, for sure – but just because this retro-rooted genre can be taken lightly, doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be taken seriously. Kaiju are evocative of everything from underground art movements, the horrors of war, and ancient Japanese myths…

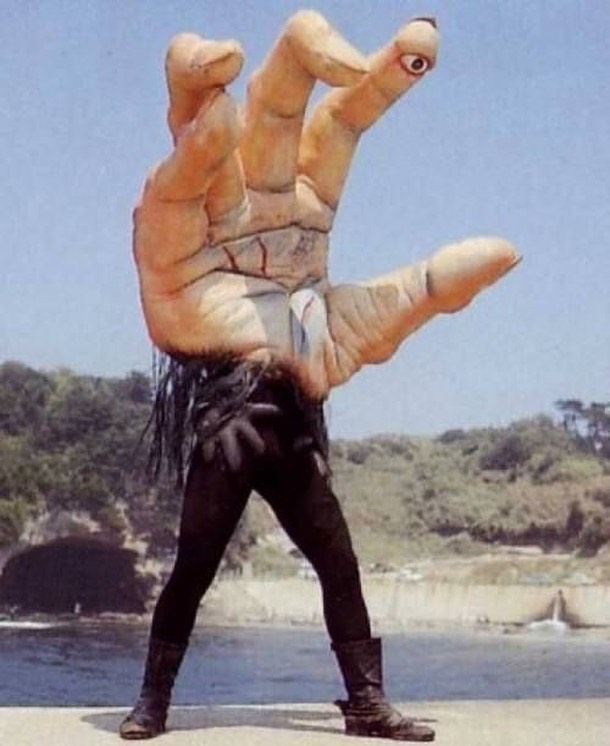

Godzilla – he’s iconic. There’s no arguing there. But one wonders what other campy kaiju creations we missed out on; the ones that didn’t manage to crossover into the mainstream media and pop-culture of the Western world. Ya know, like this guy…

Known as “Dada,” this kaiju is a humanoid alien inspired by the eponymous post-WWI European art movement, Dada, that also spread to Japan by the 1920s. The Dada monster made appearances in the 1960s-70s Japanese TV show, Ultraman, with a thirst for world domination and a suit evocative of the art movement’s inspiration from African tribal art. So for all of its camp, this monster is quite an impressive cultural melting pot.

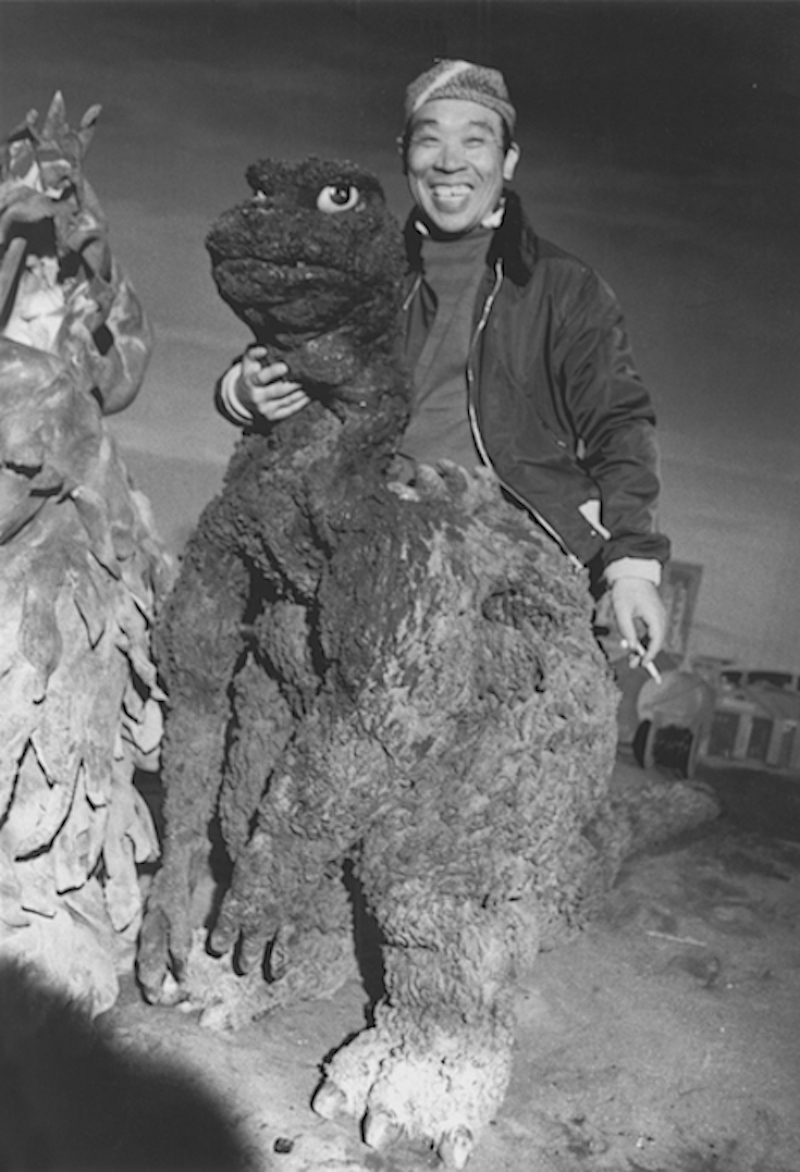

Japan’s Eiji Tsuburaya was a pioneer of special effects, and a master at making kaiju monsters like Godzilla a reality. “When I worked for Nikkatsu Studios, King Kong came to Kyoto,” he said about his passion for the monsters, “and I never forgot that movie. I thought to myself, ‘I will someday make a monster movie like that.'”

At the genre’s pique, Tsuburaya was making a new monster a week. Let’s put some on parade, shall we?

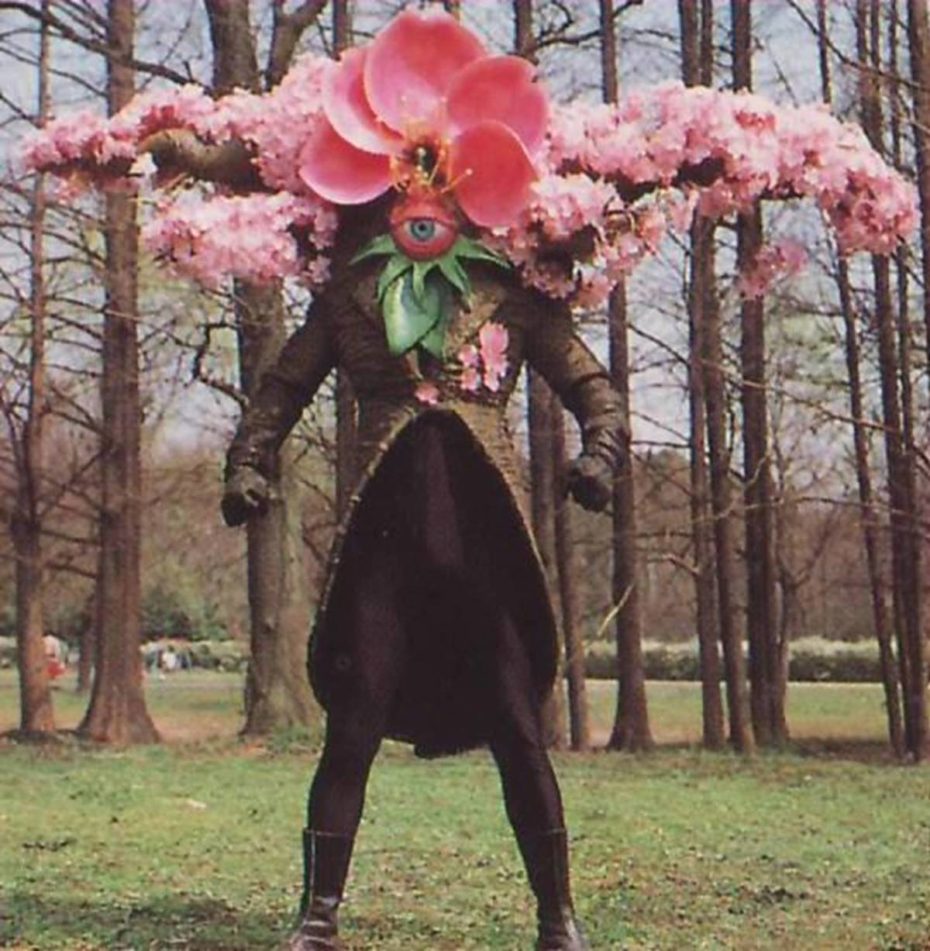

We love this flower blossom monster from the 1970s-80s Japanese TV show, Gosei Sentai Dairanger, which was the basis for the American TV show, Power Rangers. The villain fires round of petals when attacked, which is pretty damn cute.

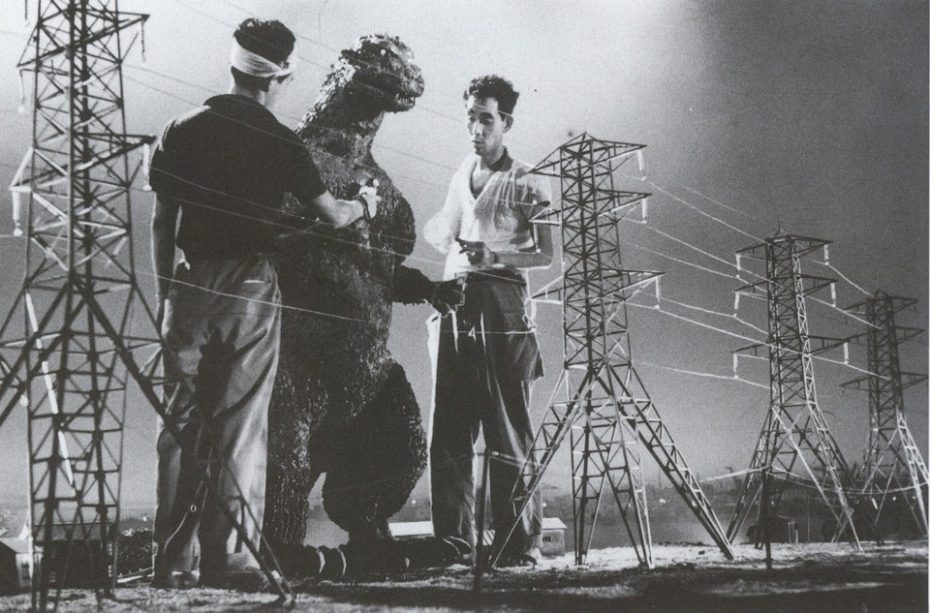

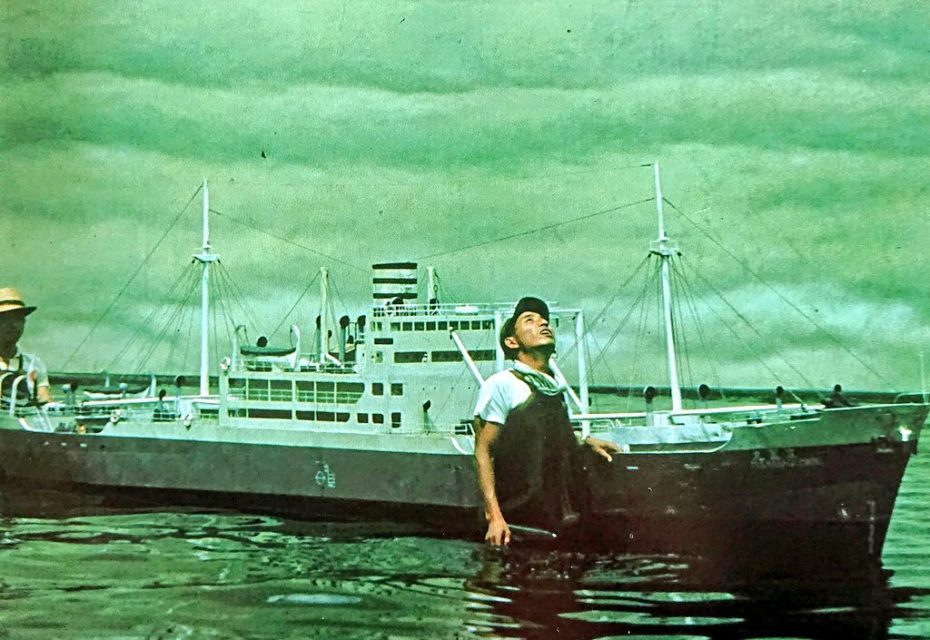

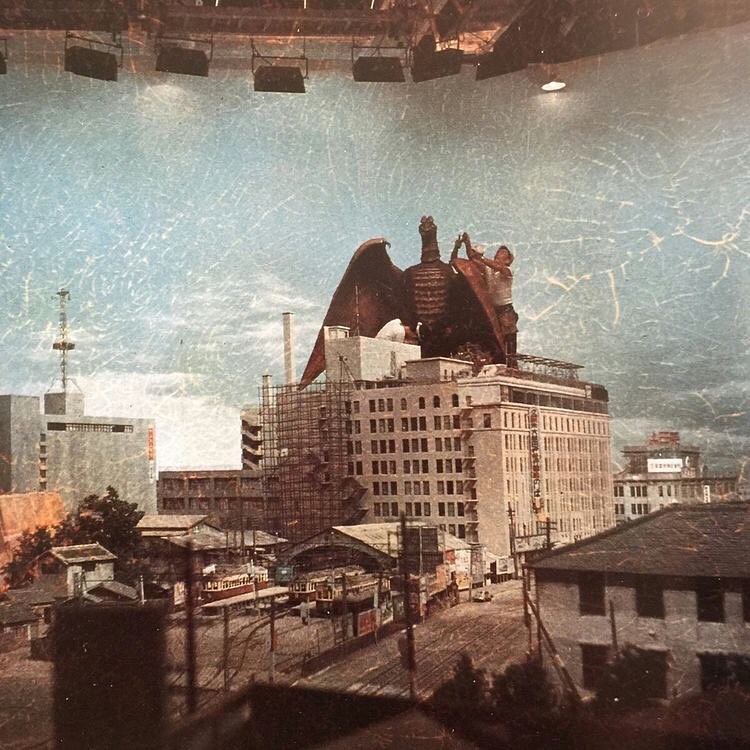

So what do all of these kaiju have in common? How did they take the temperature of Japanese culture at the time? For one, they demonstrate Japan’s pioneering role in “suitmation” which favoured actors in monster suits on a miniature set, rather than, say, the claymation creations popular in the United States.

Behind the scenes shots of tokusatsu monster movies also show the delightfully miniature sets such suited monsters trampled:

Retracing the history of tokusatsu actually us back to the 1920s, and the special effects used in the Japanese silent film, A Page of Madness (狂った一頁). So many of Japan’s silent era films have been lost, and A Page of Madness, a beautiful avante-garde film exploring mental illness, was only rediscovered in 1971. It was the first Japanese film to use varied props and special effects, like trough celluloid interpolation. In its own way, it paved the way for the bold and the weird world of kaiju.

Nor was the fear of that testing limited to Japanese cinema. A few years before 1954’s Godzilla, the US stop-motion monster film, The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms presented a parallel story of a dinosaur awakened through atomic testing. The Warner Bros. film, inspired by Sci-Fi and dystopian author Ray Bradbury’s 1951 short story, “The Fog Horn,” was a huge influence on Godzilla.

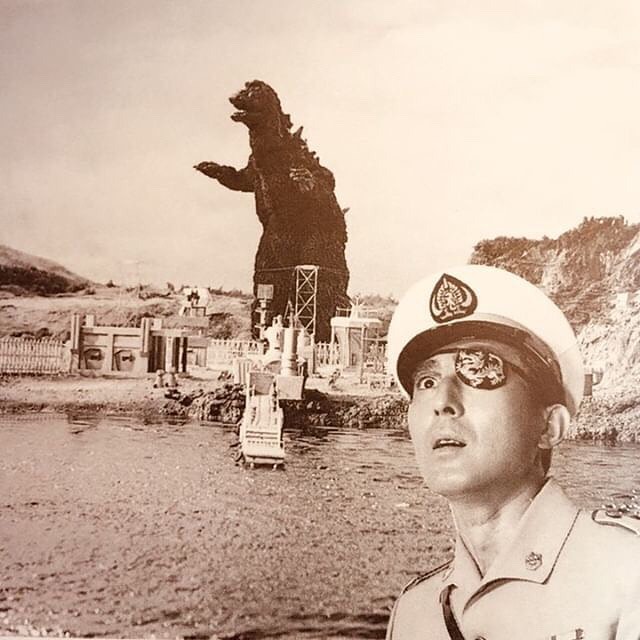

Fast forward a few decades, and we get the first major kaiju film: Godzilla (1954). When viewers first meet the giant lizard, it emerges from the water and proceeds to turn everything in its path into a wasteland in a deliberate nod to both the bombings at Hiroshima and Nagaski, as well as the US nuclear testing at Bikini Atoll.

Where Godzilla differs from his American 20,000 equivalent, however, is in how much it unpacks about the nuances of war, recovery, and of course atomic weapons. Godzilla isn’t just awakened by nuclear testing, but eerily empowered by it. The very texture of the monster’s skin, said designers, was inspired by the keloid scars visibe on the surivors of Hiroshima. It’s dark stuff.

Like the 20,0000 Fathoms dinosaur, Godzilla evokes our planet’s prehistoric past – at once recalling a time before humankind, and showing the tragic, distorted imprints of its violence. Its very reflective of the Shinto God of Destruction, which Godzilla B-movie maker Shogo Tomiyama says operates not in service of humankind, but rather the laws of nature. “He totally destroys everything and then there is a rebirth,” he says, “Something new and fresh can begin.” Godzilla isn’t good or bad. It just exists.

Shinto is an 8th century Japanese religion, and was the state religion until 1945. Not unlike the Greeks, practitioners are polytheistic and worship an array of gods and deities called yokai, mysterious creatures that often have animal characteristics, though they can also be human, animal, plant, object or even a natural phenomenon and force of nature. Sound familiar?

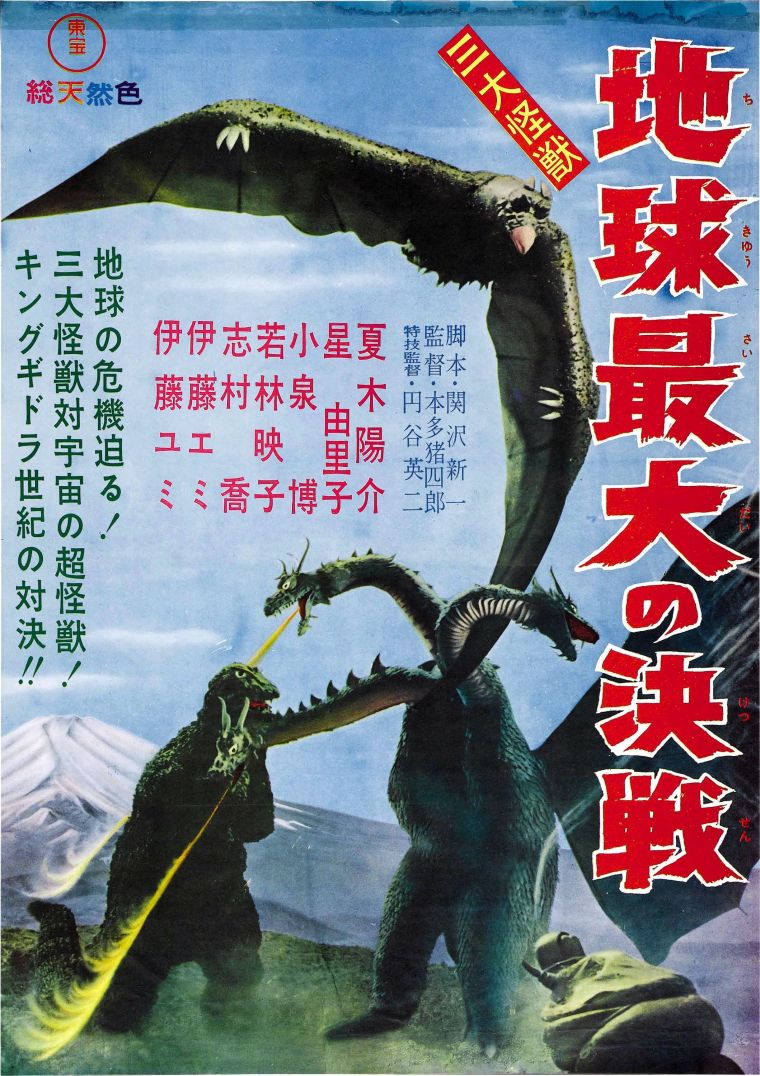

There have been dozens (dozens!) of Godzilla films over the years, to say nothing of the many comic books and TV shows. Fun fact: the chilling, iconic sound effect for Godzilla’s voice was made by manipulating the recording of a glove or key rubbing up against on a contrabass. In the West, Godzilla’s specific political symbolism is often nixed for simpler disaster movie tropes. Still, early kaiju monsters served as codifiers for real political tensions, and weren’t limited to the Godzilla monster; consider the three-headed space dragon “Ghidora,” a Japanese metaphor for the growing power of China.

During the United States occupation of Japan, it was forbidden to publicly venerate the traditional Shinto values and mythology so foundational to Japanese culture; these gods and goddesses of earth, wind, fire, and air. Kaiju monsters were very much inspired by those attributes, and there was something about having a person in kaiju costumes that added a layer of depth. So much so, that one can even find godzilla action figure toys that show the actor half-way in the monster’s exoskeleton, which was so heavy it could only be worn for a few minutes at a time.

Growing up, Film Studies professor Ramie Tateishi says he was struck not only by Godzilla’s talent for destruction, but embodiment of an even scarier reality. “How do we know what we know? How is information managed?” Tateishi told KPBS in 2016, “in the original Godzilla, there was this subplot about the government withholding information from the public.” Such retro kaiju weren’t just monsters. They were cathartic manifestations of mistrust, trauma, and possibility that the Japanese were finally able to explore once the US cleared out. Campy, creepy, weird and in their own way, empowering for the next generation.

Want to dive even deeper into the world of tokusatsu monsters? Visit the Japanese-owned Librairie Junku in Paris or order books and comics online. If you don’t find what you’re looking for, they’re also happy to order it. Americans, check out the various branches of the Japanese bookstore Books Kinokuniya in New York, Los Angeles, and other cities.