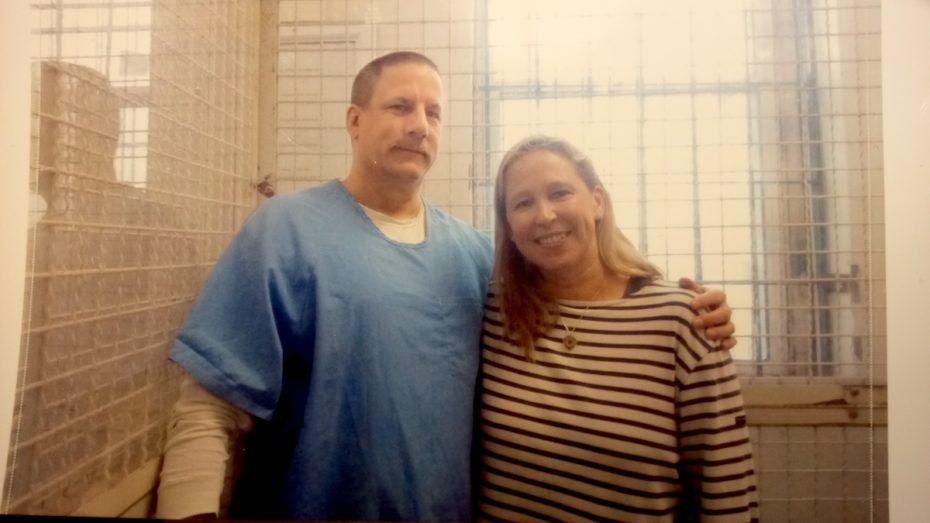

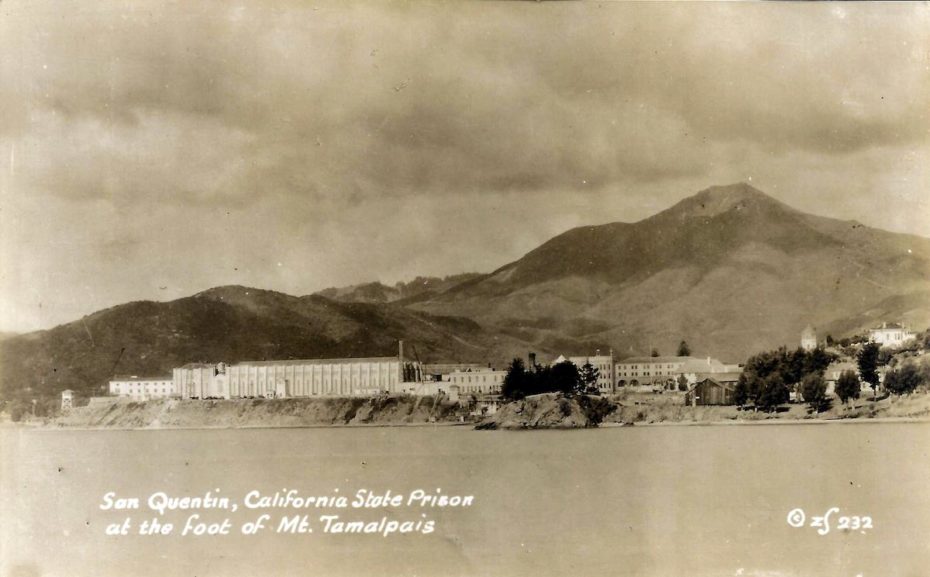

Nicola White didn’t leave her heart in San Francisco, she left it in the San Quentin State Prison, just over the Golden Gate Bridge. “It’s funny,” she tells us by phone from her native England, “I never set out thinking, ‘I’m going to Death Row and I’m going to start a project with these prisoners – these artists.’ It just happened naturally, the more time I spent getting to know them as people.” Since 2016, Nicola has been curating a collection of creative works with her initiative, ArtReach: Reaching Out with Art and Poetry from Death Row, which exhibits and sells the paintings, drawings, sculptures, and words of Death Row inmates at what has been called “the most populous execution antechamber in the United States,” San Quentin State Prison. It’s a place that has long held a dark fascination for the American public, appearing in countless films, books, and songs; it even hosted Johnny Cash’s iconic 1969 concert, in which he bellowed out, “San Quentin, I hate every inch of you” to cheers of inmates who finally felt seen. In its own way, Nicola’s project continues that effort by offering a glimpse into the everyday life on Death Row, and by encouraging a multi-sensory exchange between inmate-artists and the outside world…

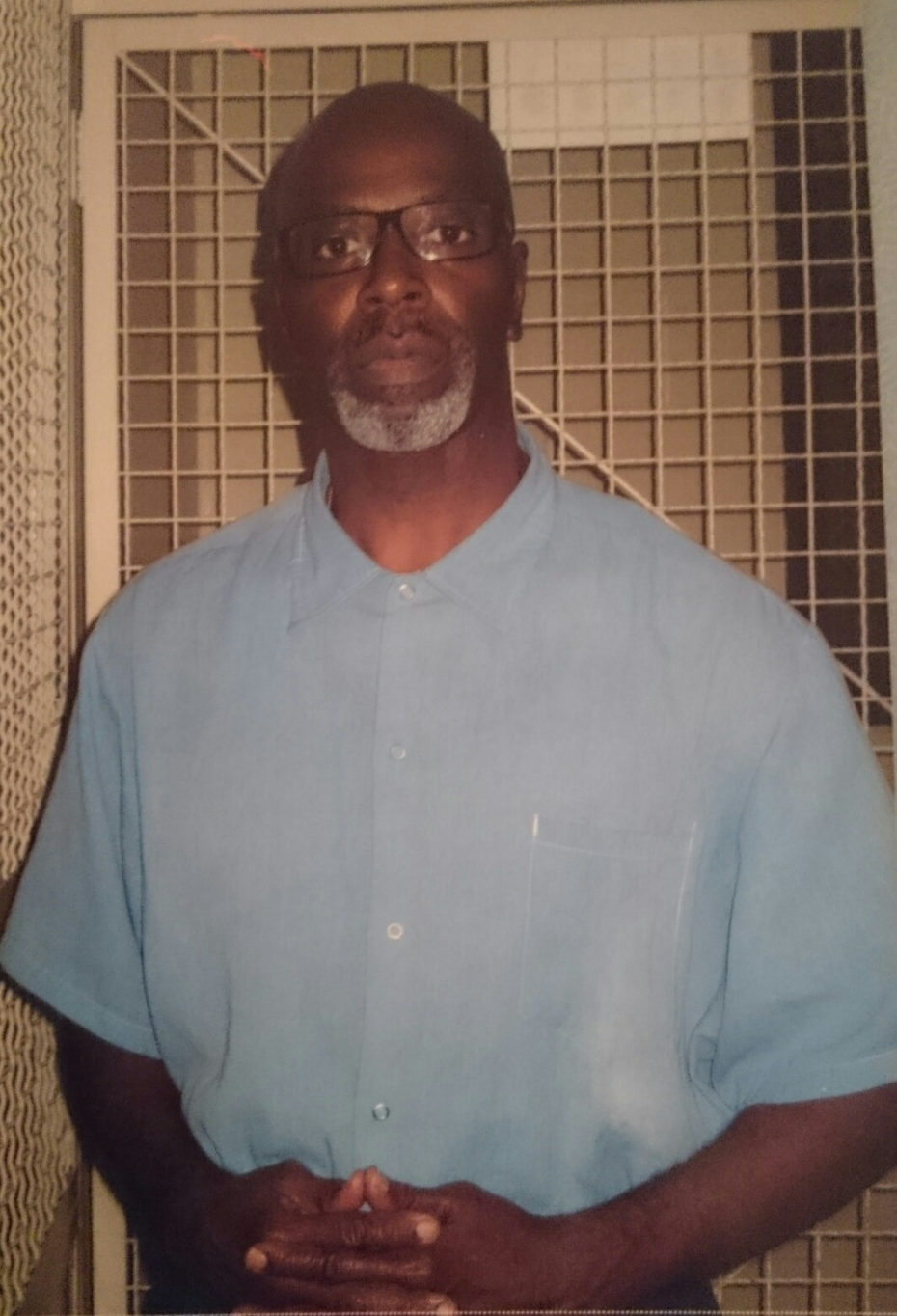

For Nicola, it all started with a letter. “I met a woman in a gym changing room,” she says, “who was telling me about a UK charity she belonged to that connected people [as pen pals] with prisoners on Death Row in the US.” Today, Nicola works in the arts full-time, but back then she was eager to find more meaning outside of her then-corporate life. So she picked up a pen, and “through the lost art of letter writing” began a new friendship with a Death Row inmate at San Quentin – a man who had a lot to say about his life, and a lot of art to show for it as well. One day, she finally flew out to meet him. “My visit was for 5 hours, which seems like a very long time but it went by so quickly,” she says. “We talked about so many different things, including art and poetry. He used to send beautiful homemade cards and I’d asked who did them. He explained how so many of the prisoners make art, learning to draw and paint with all sorts of materials.”

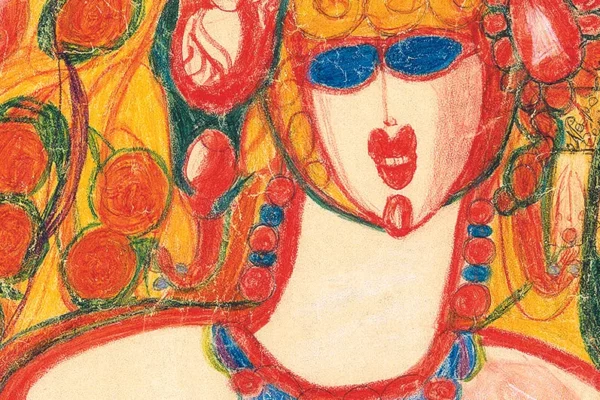

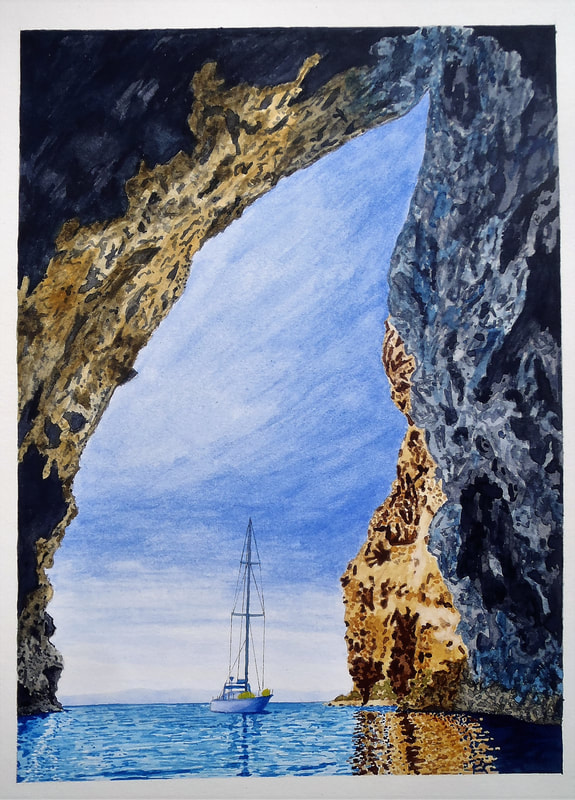

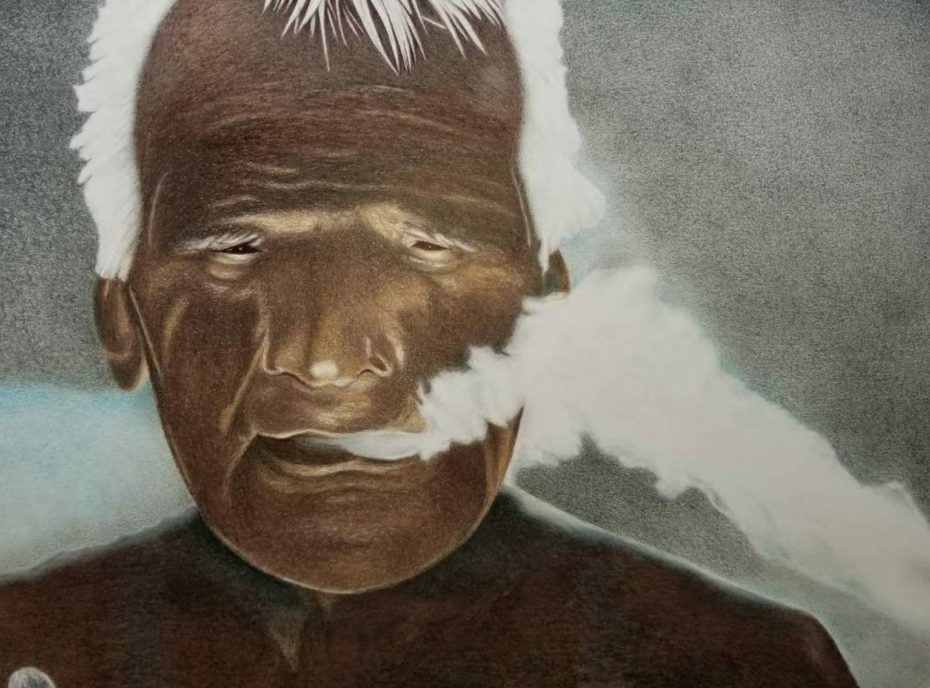

Turns out, M&Ms (the candy) make great paint. So does coffee, tea, and that “really artificial orange juice,” says Nicola, “because it’s really pigmented. Inmates get so creative. One guy makes incredible flowers out of what is basically toilet paper. Insects made out of plastic spoons. Necklaces. The work is so intricate. Some of them use feathers and their own hair for brushes as well.”

And just where did all this art end up? Most of it is traded between inmates, or taken by lawyers to give to inmates’ families. Some of it goes on display in the San Quentin “Gift Shop” (yes, gift shop). “But it has very limited hours, and isn’t the most accessible, I would say,” says Nicola, “so we came up with this idea to start gathering works from inmates.”

How on earth does one raise publicity, in a prison, for soliciting works from self-isolated inmates? Flying kites. “Not the kind you know,” Nicola clarifies, “but a ‘kite’ in prison is a small slip of paper that inmates will dangle by a thread to communicate.” The project’s kite made the rounds, and with the help of a lawyer group called Amicus, they were able to gather some 50 artists’ work to display internationally, with proceeds from any sales going directly back to the inmate artists to buy more supplies.

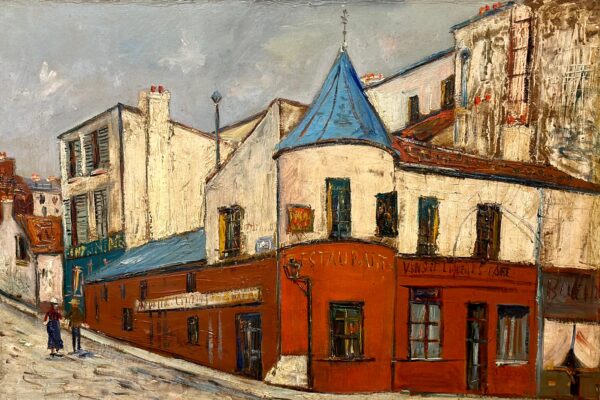

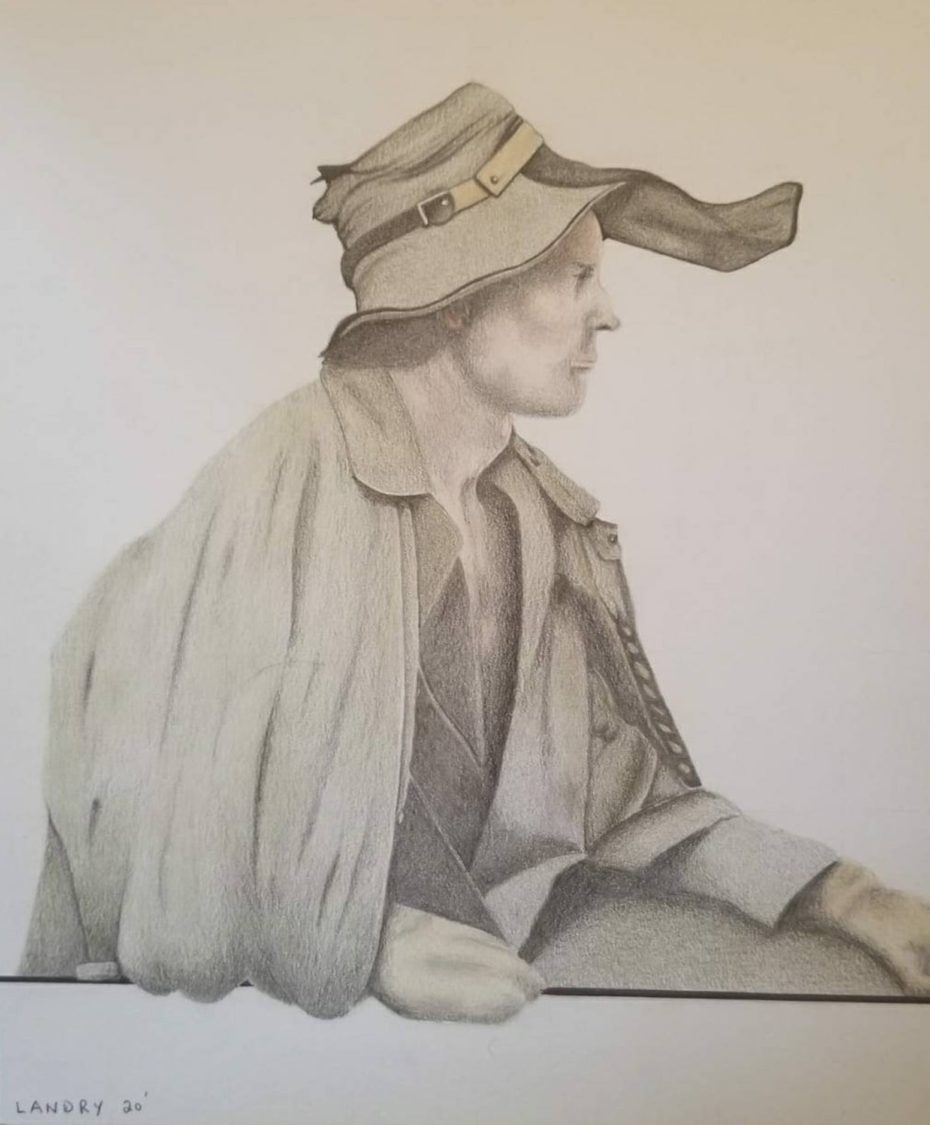

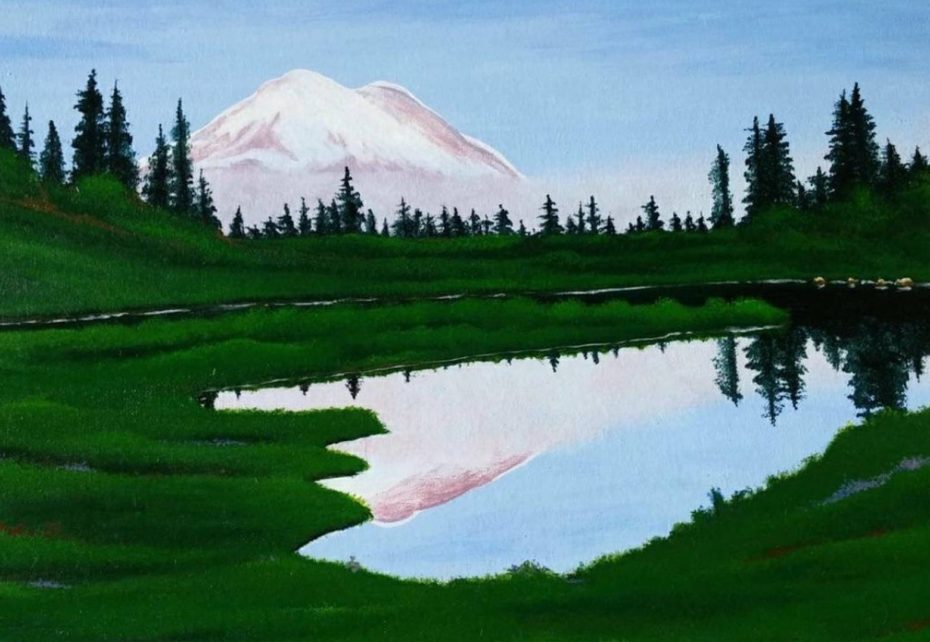

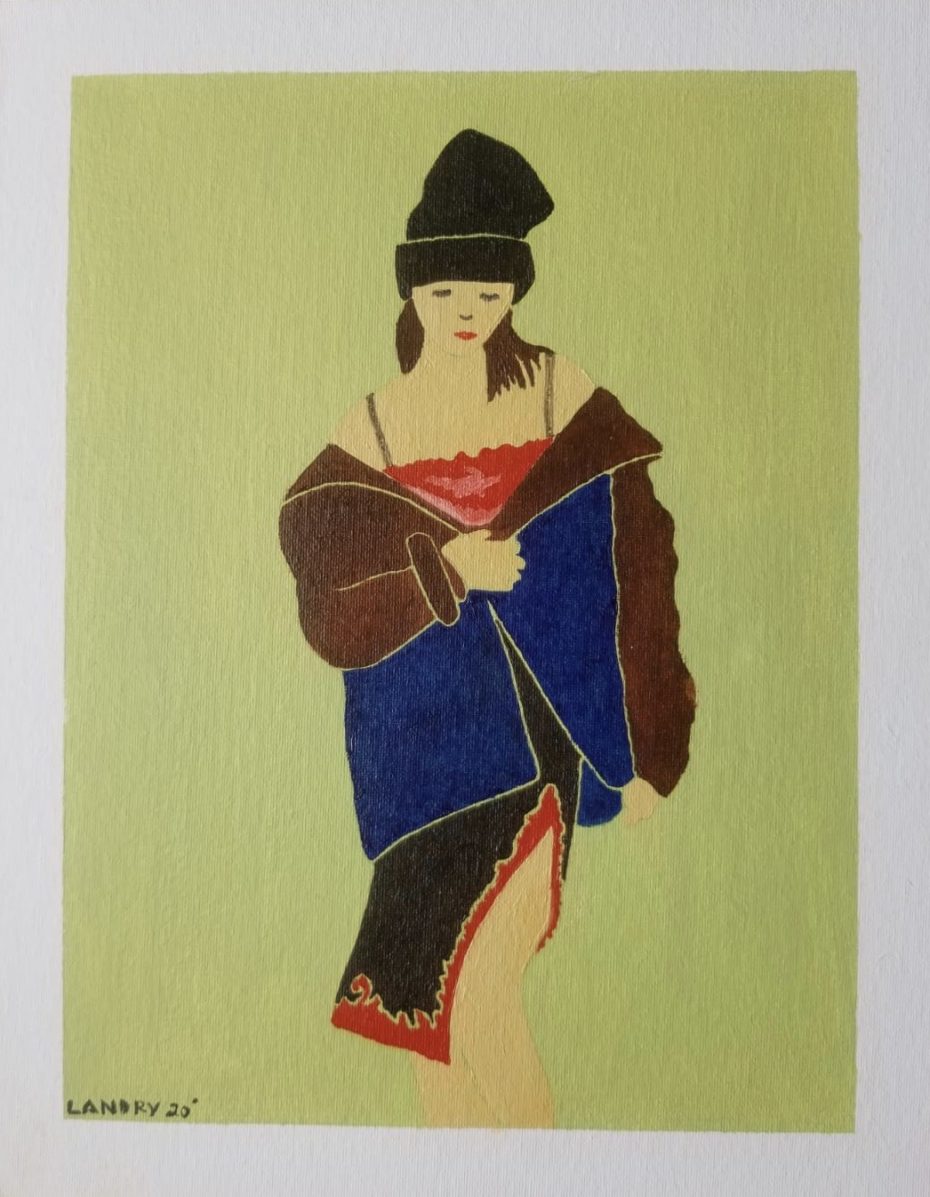

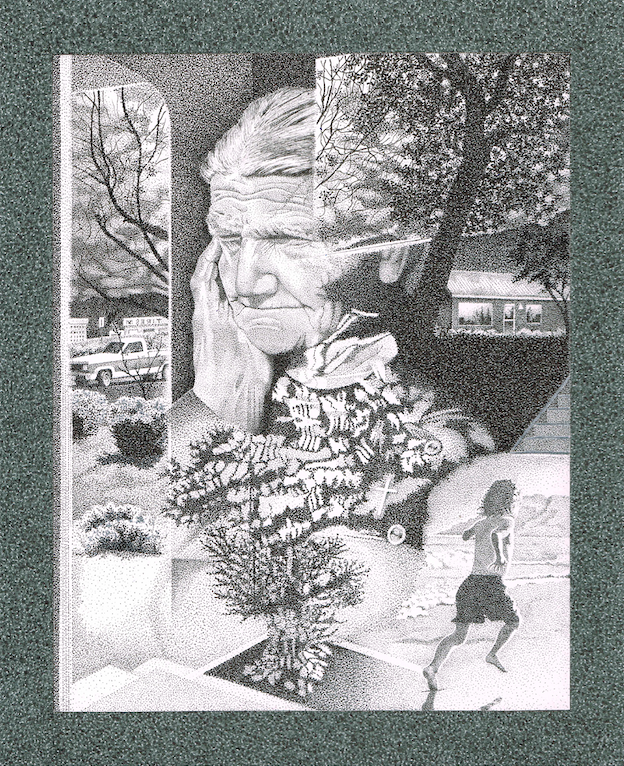

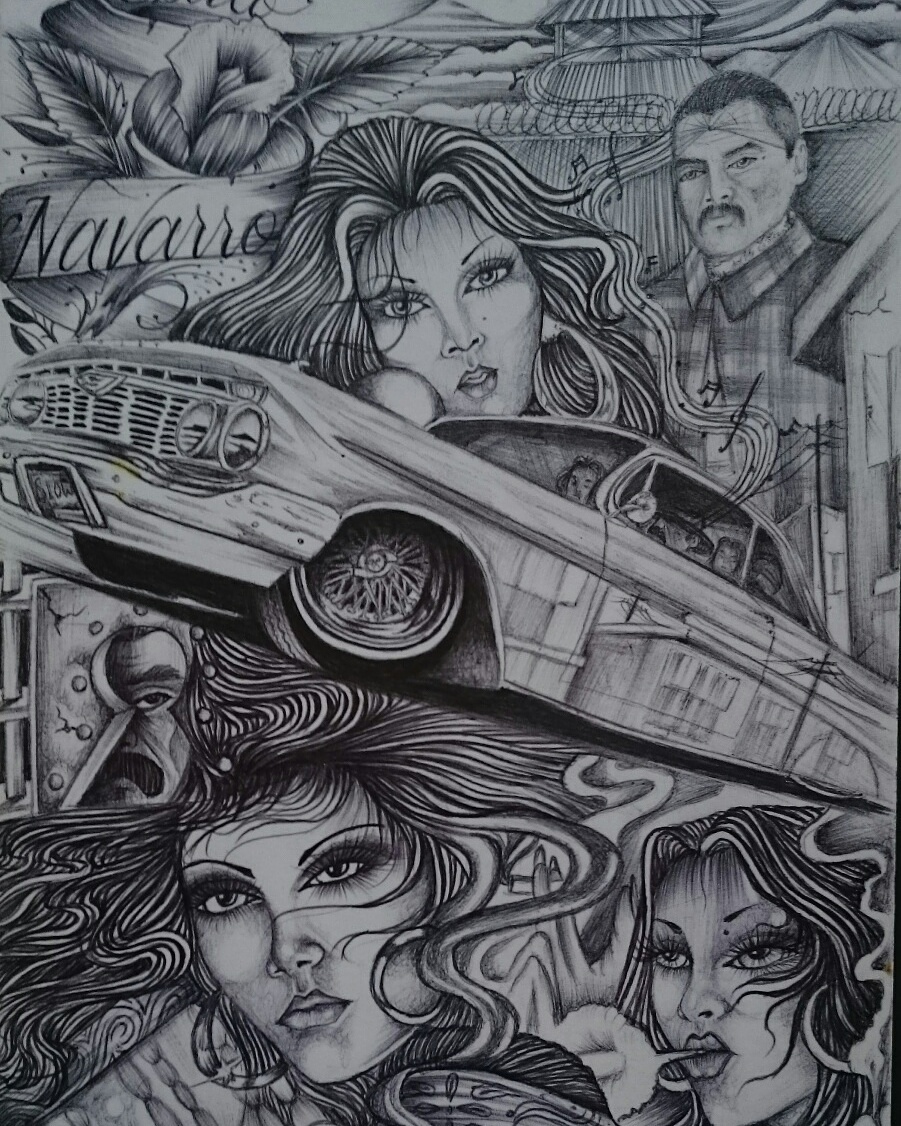

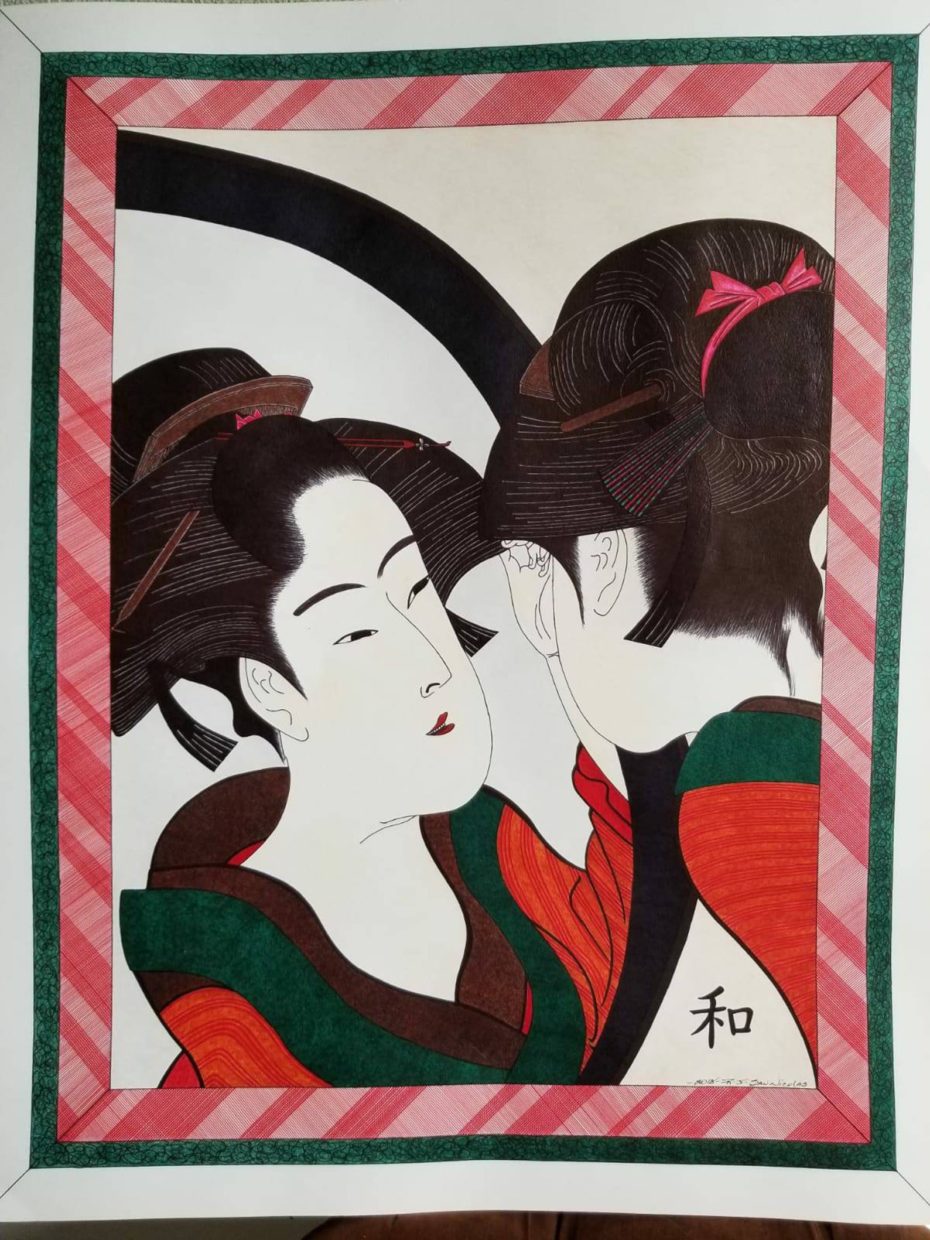

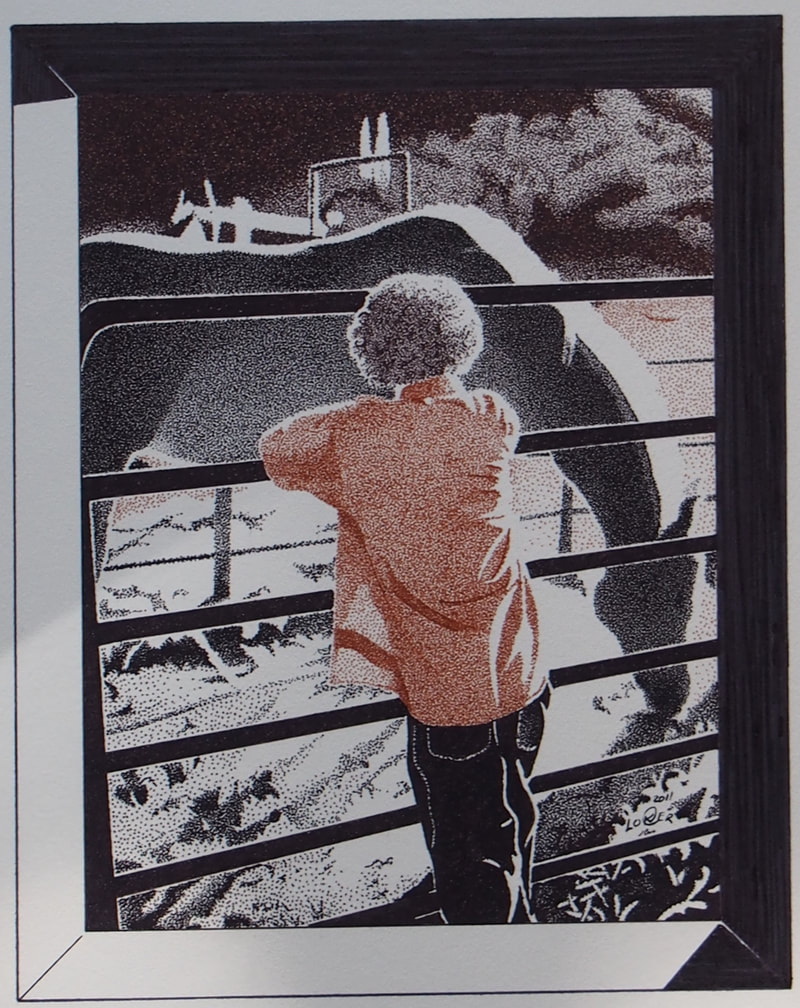

There are pastoral landscapes, and Old Master-esque still lifes; fine line drawings, and dot paintings by a man named Keith Loker that bring French pointillism painter Georges Seurat to mind. But truthfully, the works surpass such labels and comparisons. They weren’t born from any formal artistic institution, and don’t grow within in parameters.

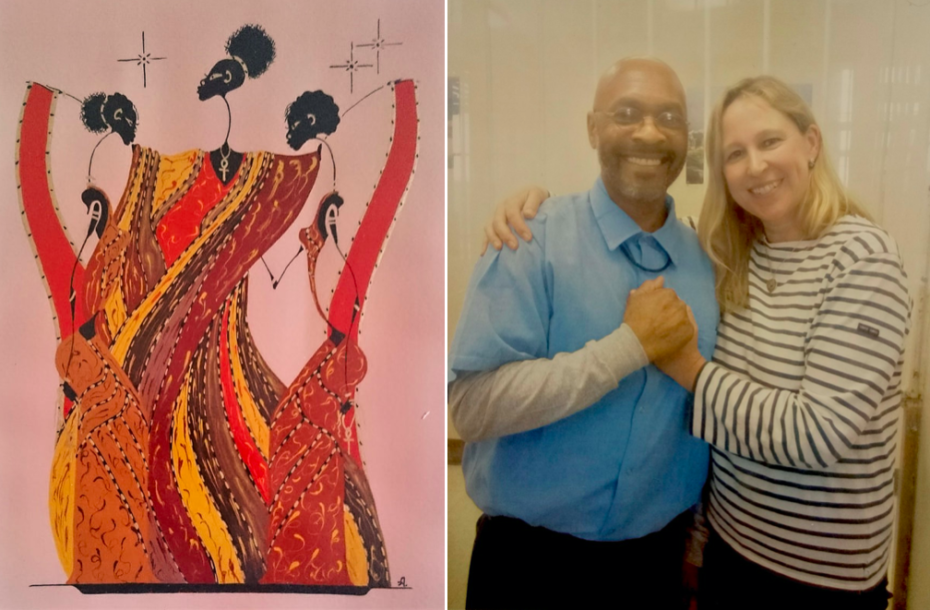

“The artists I’ve been in touch with are all self-taught,” says Nicola, “Inmates will support one another with teaching in the yard. Alphonso Howard, for example, is a painter who makes these beautiful tribal inspired pieces with techniques he was taught by another Death Row inmate.”

“Steve Champion is a wonderful poet to whom I’ve grown close. He always says writing helps him to travel without moving. He was also friends with one of the last people to be executed on San Quentin, Stanley “Tookie” Williams. He, Tookie, and another man named Craig Ross created their own little ‘university’ in which they all taught one other about everything – Geography, History, English. Now Steve is like a walking encyclopaedia.”

We’re delighted to bring you some exclusive recordings of Steve reciting his poetry from a prison payphone. The following is entitled, “If There Is”…

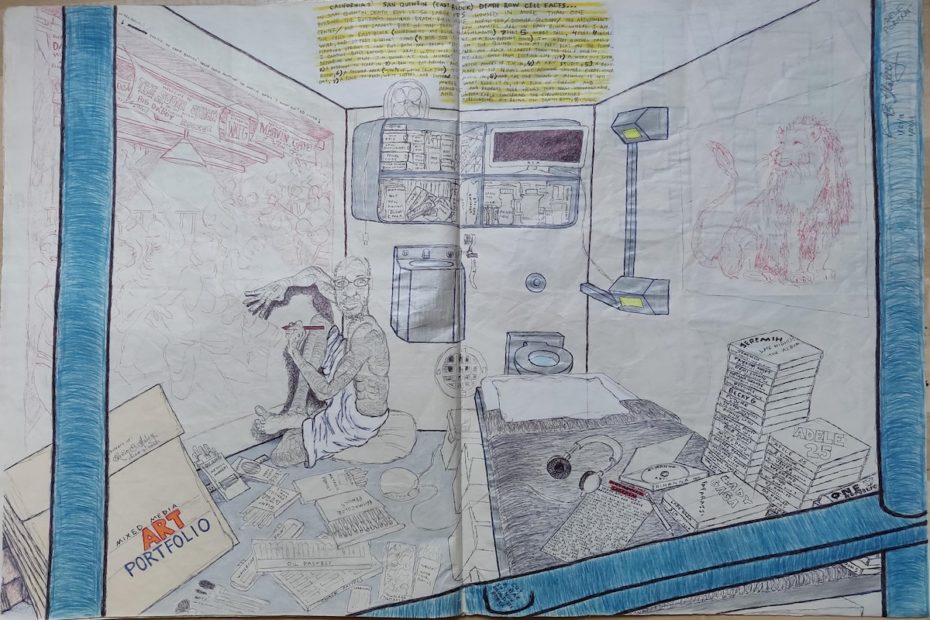

Most inmates use their beds as a workspace. “There is a ‘Hobby Program,’” says Nicola, “which is just a term that means they are allowed to purchase supplies, but there is no social space for them to make art.” She holds up a remarkable cardboard model of a cell – a dollhouse? Diorama? – during our Zoom call.

“It’s made by a man named Christopher Spencer,” she says, “It has the toilet, sink, bed. It’s the exact mini dimensions of his 7ft by 10ft by 4ft cell.” It even has a functioning lock for the door. As she turns it, another thought clicks inside the viewer – what am I supposed to feel?

There’s beauty, ingenuity, and heartbreak in these pieces. But most of all, there’s healing. Consider the artist behind the dot paintings; “He said it helps him feel in control,” says Nicola, “and Steve, for example, has grown so much since he came to San Quentin at around 18-years-old. He’s in his fifties now, and just not the same person. As he puts it, it’s like being fossilised in time at the worst moment of your life.”

San Quentin is just a short drive from San Francisco proper, and was founded in 1852, making it the oldest prison in the state. While current governor Gavin Newsom has outlawed the Death Penalty, the conditions under which Death Row inmates live are still harrowing, and increasingly dehumanising in the midst of Covid-19. Just last week, Death Row inmates were revoked phone use indefinitely, leaving many families in the dark on their status.

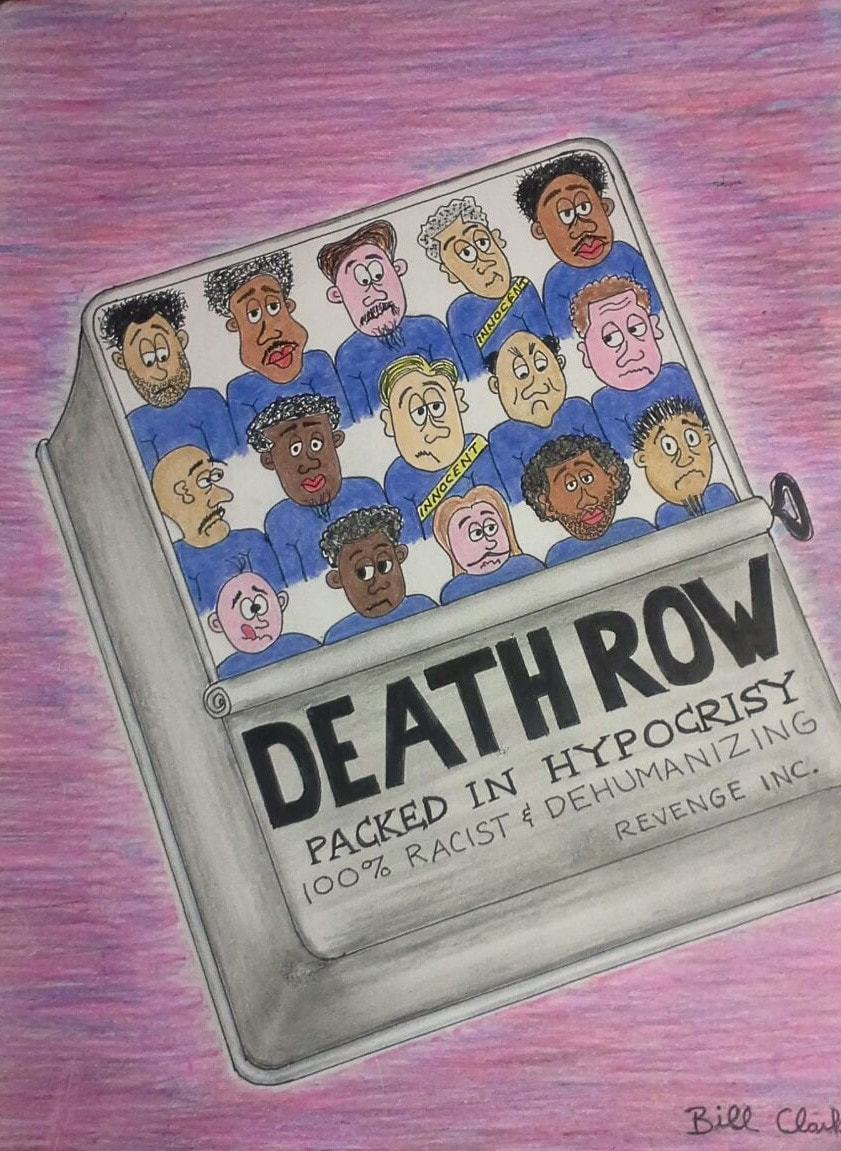

The line between Death Row and ‘normal’ incarceration can be thin, even interchangeable. “I am not at all trying to minimise the nature of some of these crimes,” says Nicola, “but it all depends on the jury, the judge, the year.” Of the over 700 men currently on Death Row, the majority are incarcerated for crimes that could have merited a more less intense sentence.

Perhaps the question isn’t, “Should I buy art from Death Row?” but rather, “Do I support the right to make art? To heal?” The power of art therapy in rehabilitation has long been proven, and a means one would hope any institution calling itself a “correctional” facility would support. As our poet Steve Champion says, “Singing heals my wounds, softens my heart. Men sing in solitary confinement to free themselves from boredom. I sing to stay human.”