Every once in a while, pop culture gives us a duo whose legacies feel almost magnetically intertwined. David Bowie and the Japanese designer Kasai Yamamoto created some of the most iconic, gender-bending stage outfits the world had ever seen. Yet, for being such a fashionable and cultural force on East and Western stages, Yamamoto is arguably less well known than Japan’s “Big 3” designers, Issey Miyake, Rei Kawakubo, and Yohji Yamamoto. In light of Yamamoto’s recent passing last week, we’re diving into his portfolio to soak up all the colour, inclusivity, and joy that his clothes gave to Bowie to learn more about this curious man who once admitted to owning no car, but two air balloons.

How exactly do you dress a rockstar whose aesthetic falls somewhere between – to use Ziggy’s own words – an “alligator,” “space invader,” and “a rock ‘n’ rollin’ bitch”? A man whose bold defiance of gender roles was something we’d only ever seen in, oh, maybe Western glam rock wresting?

The genius of Bowie’s vision for himself was always in his talent for being an interdisciplinary chameleon; in one 1990s interview, for example, he predicted the growing power of the internet as “an alien life force,” and regretted not diving deeper into computers within his own work, much to the shock of the interviewer. In other words, Bowie was never boxed in by one medium or launching pad. He and Yamamoto had that in common.

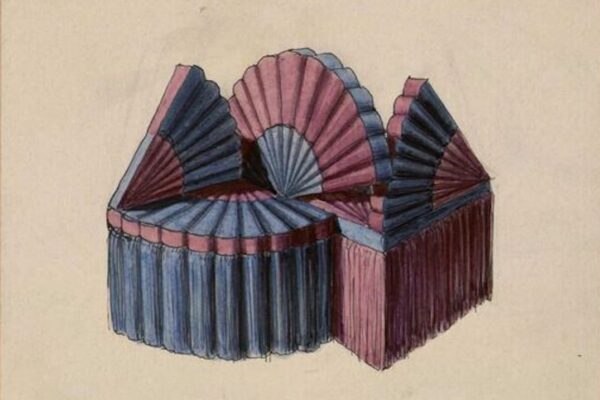

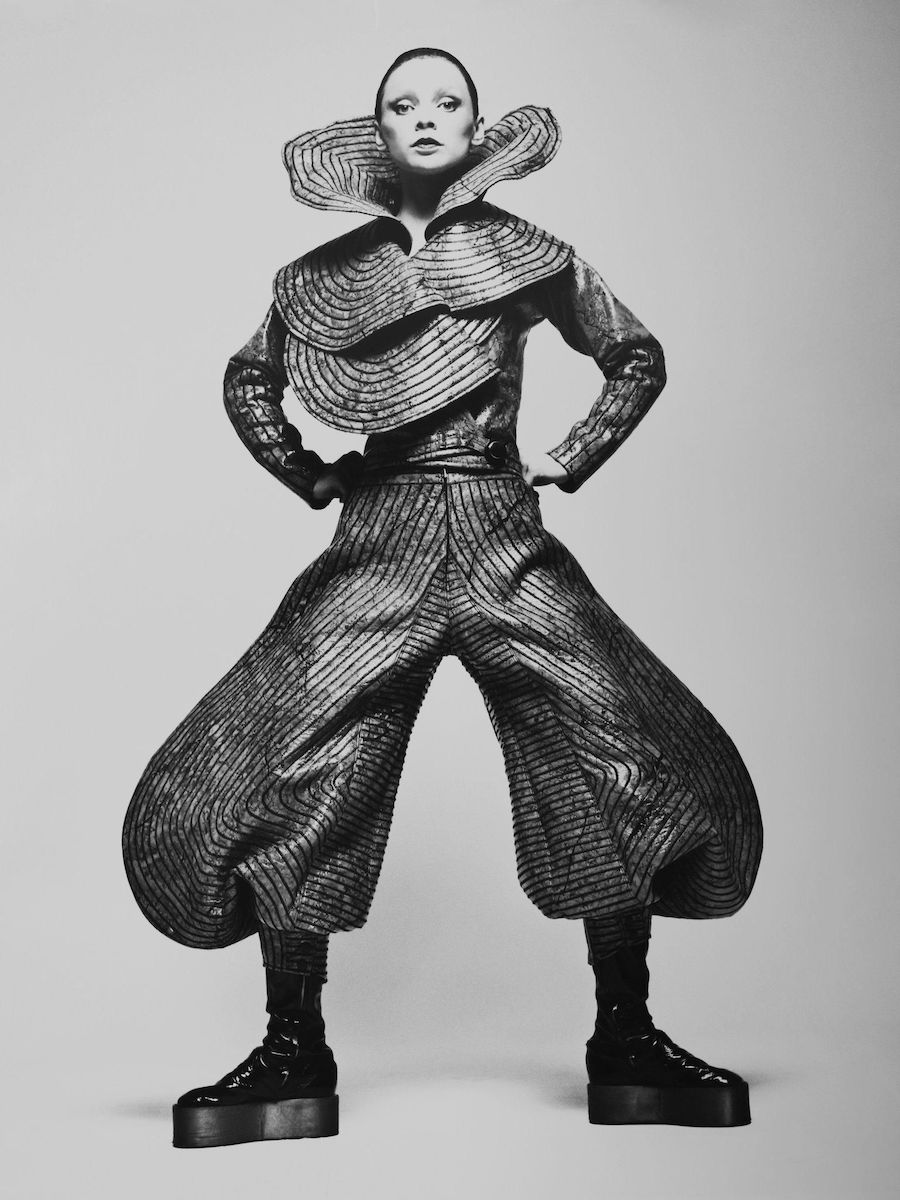

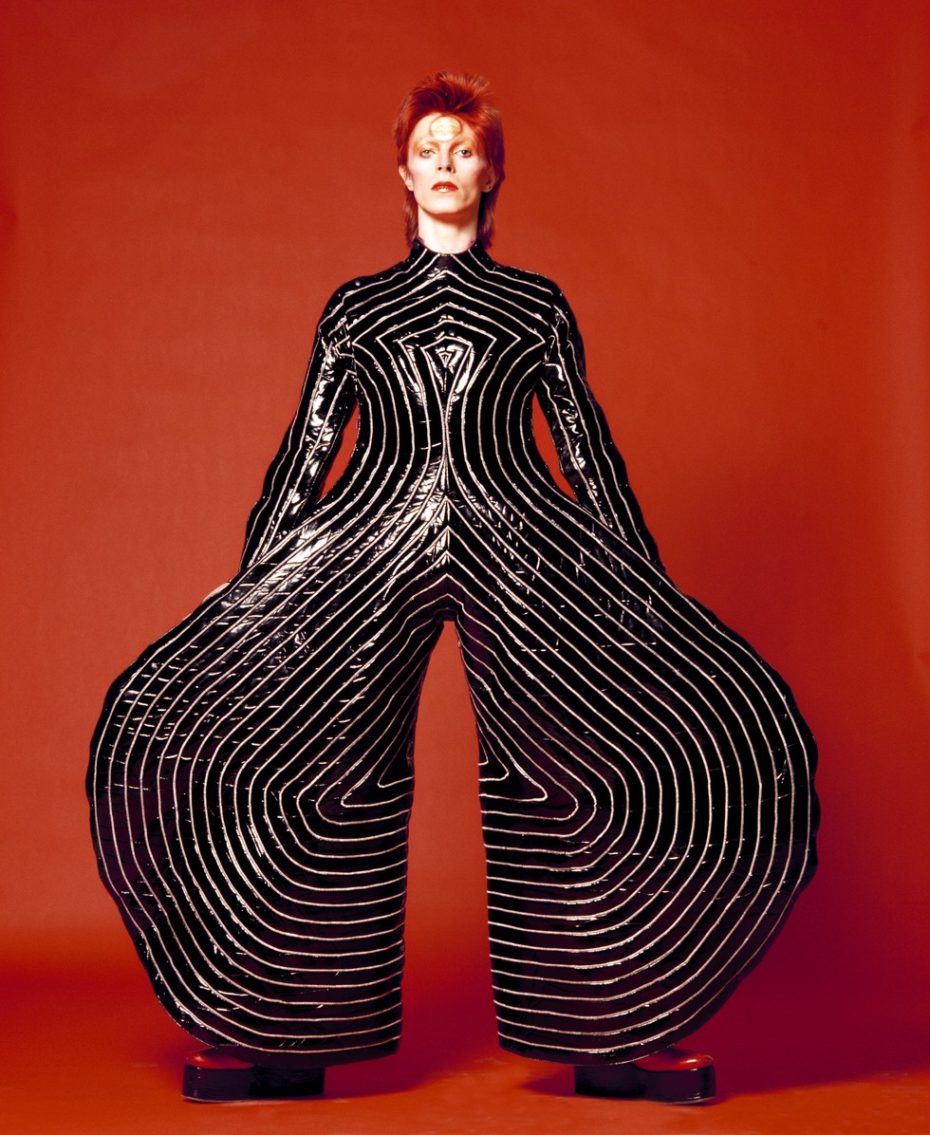

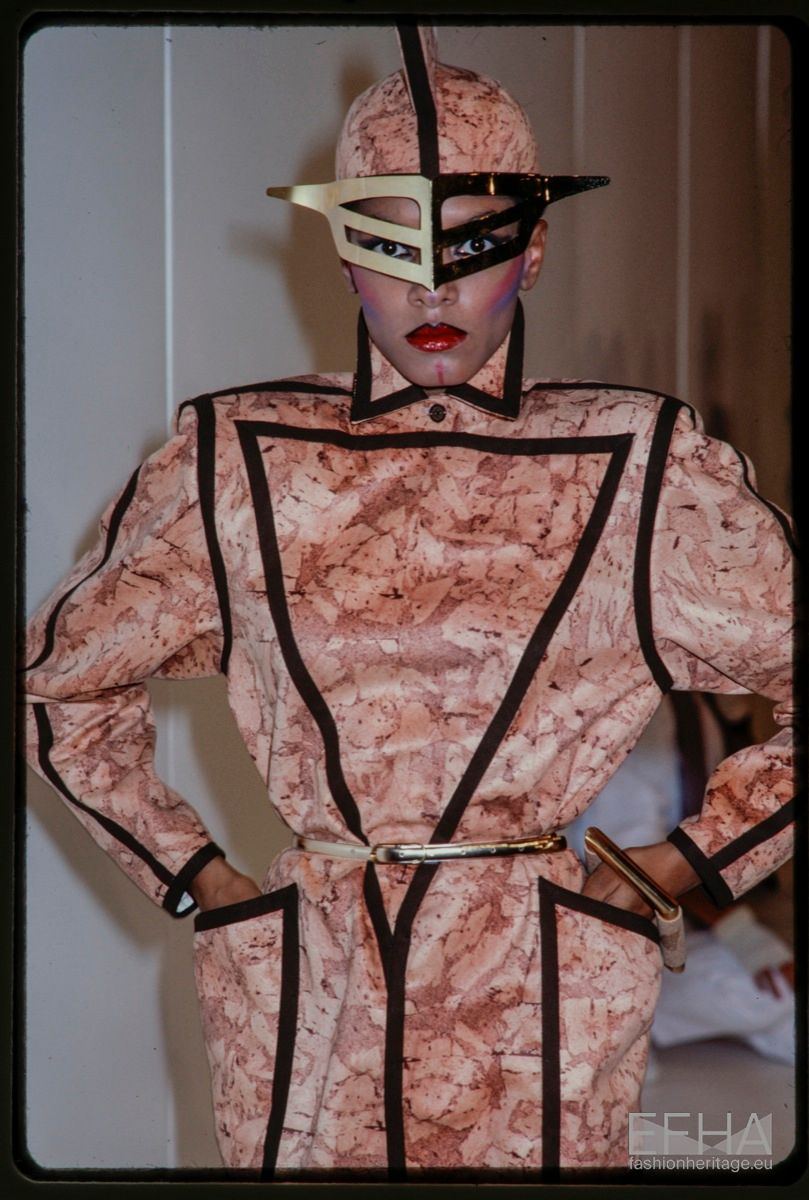

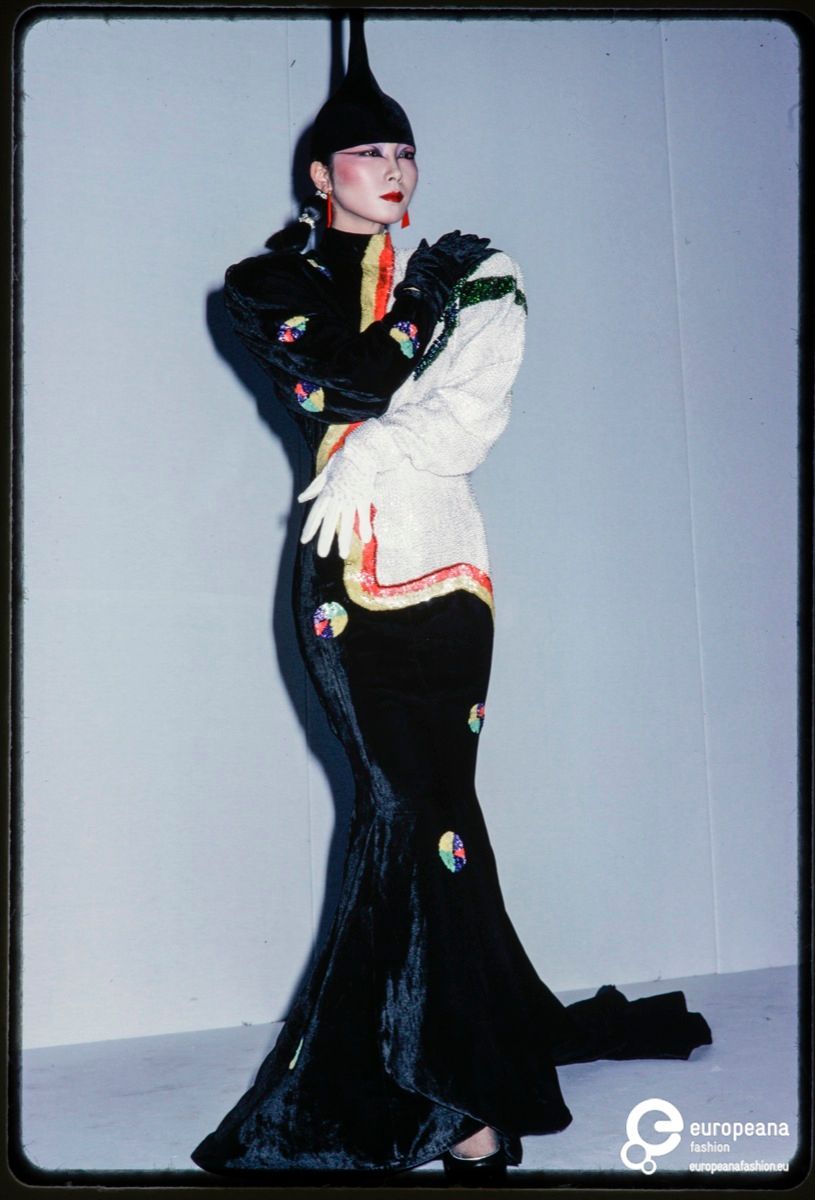

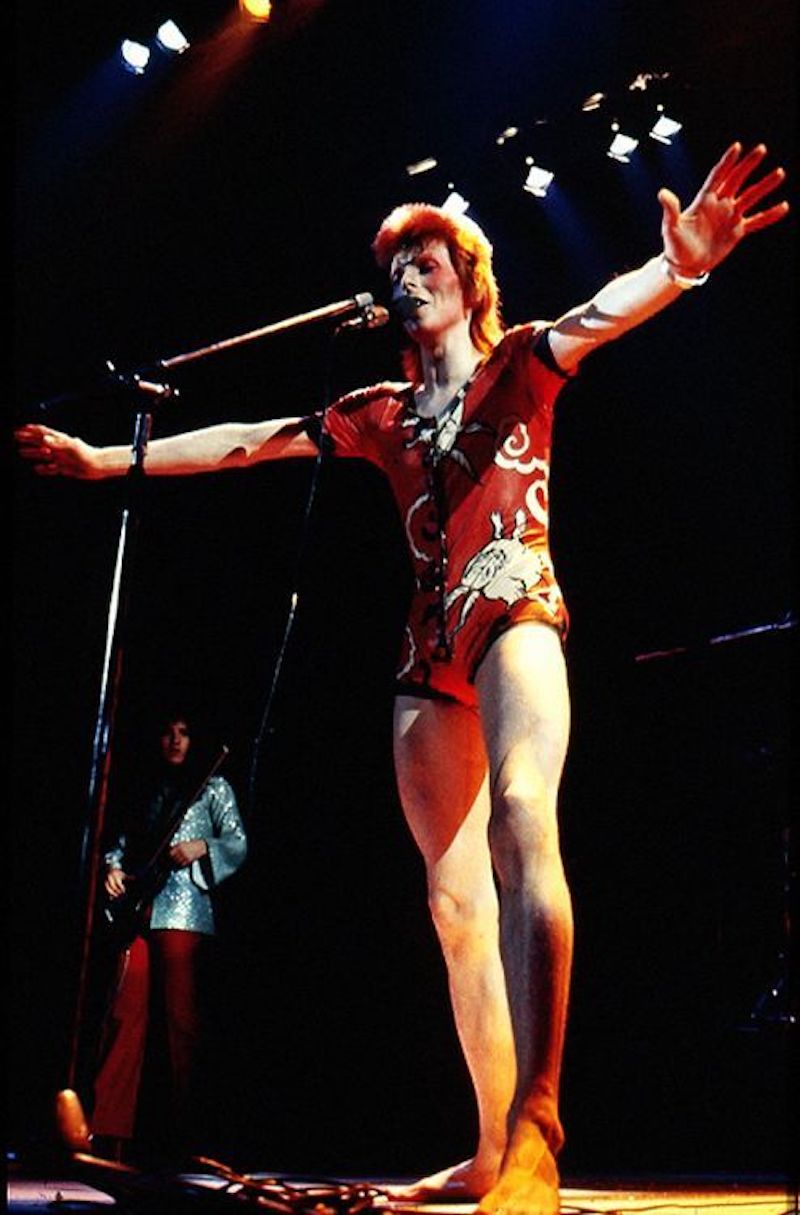

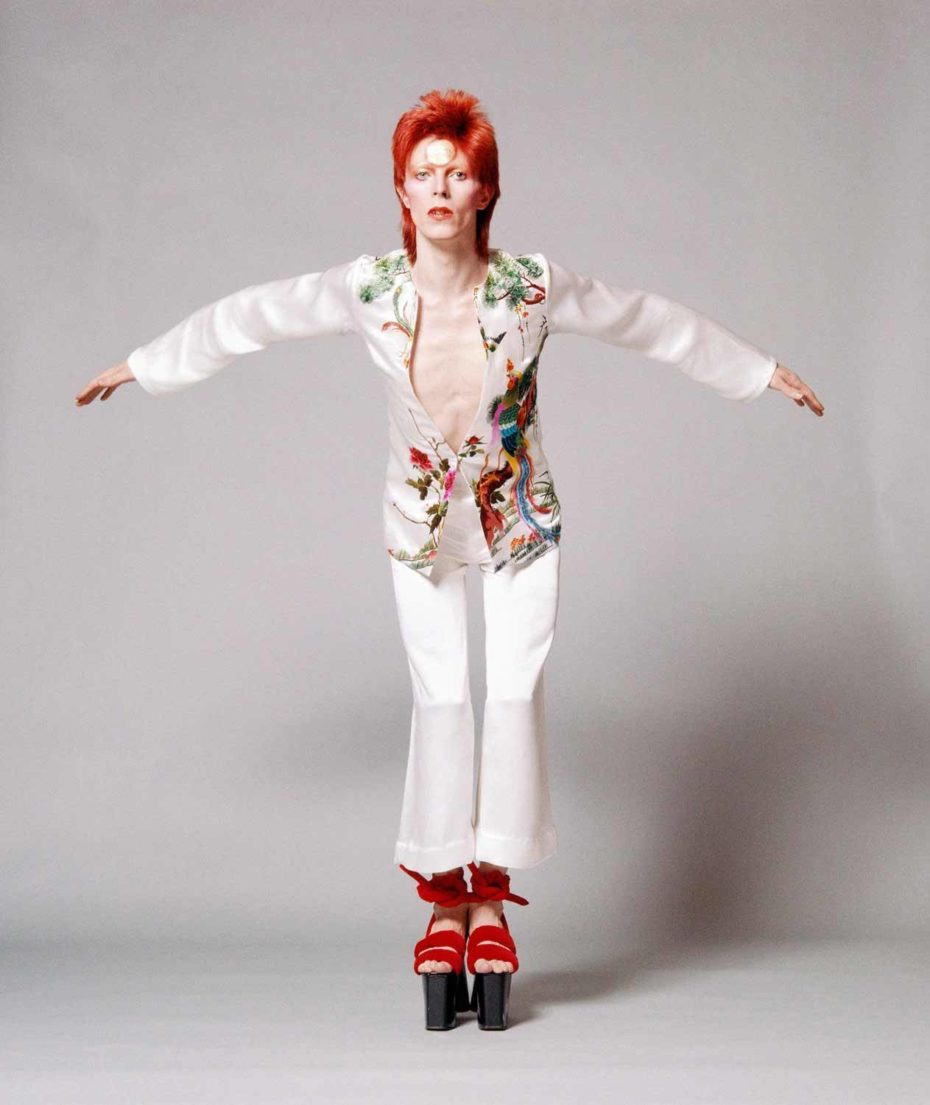

Yamamoto was born in Yokohama, Japan in 1944, and actually studied Civil Engineering and then English before pulling a total 180, and gaining acceptance to the esteemed Bunka Fashion College in Tokyo. We see all three of those formations in his designs; we feel the presence of history and narrative in the pieces, we see the ways a pant can be engineered to bring real and imaginary movement. We’d argue this is one of Yamamoto’s most iconic silhouettes:

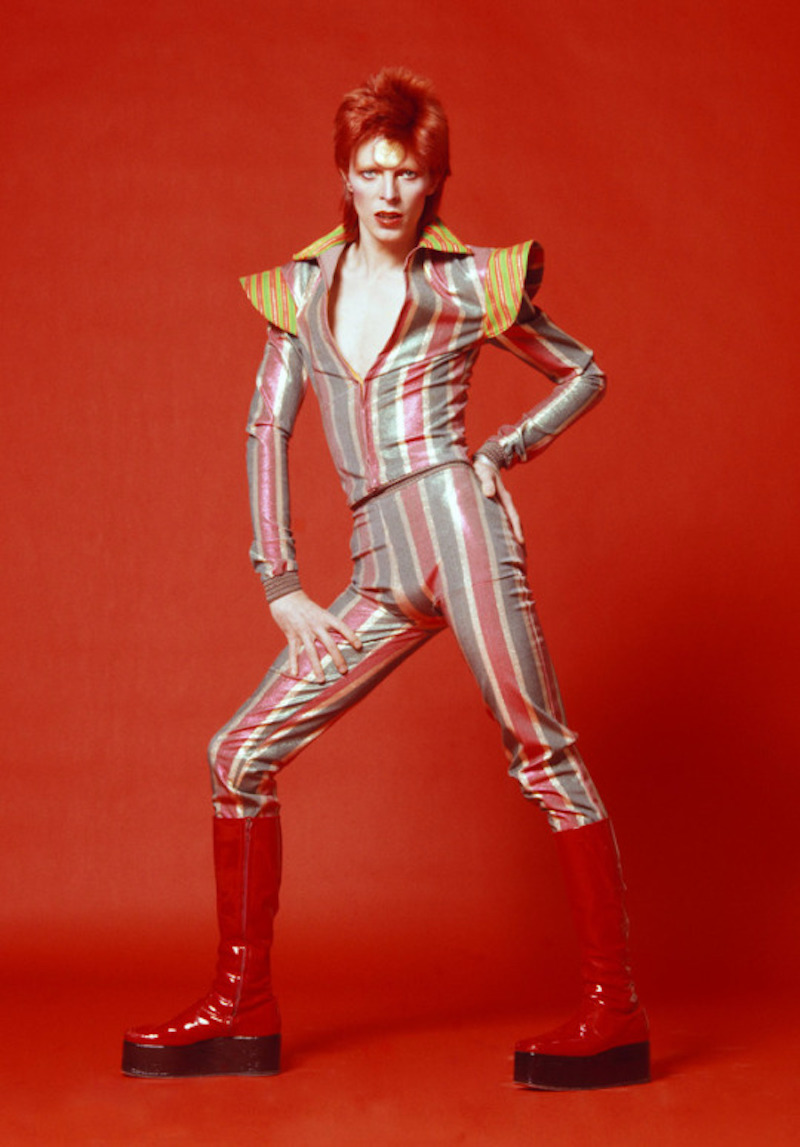

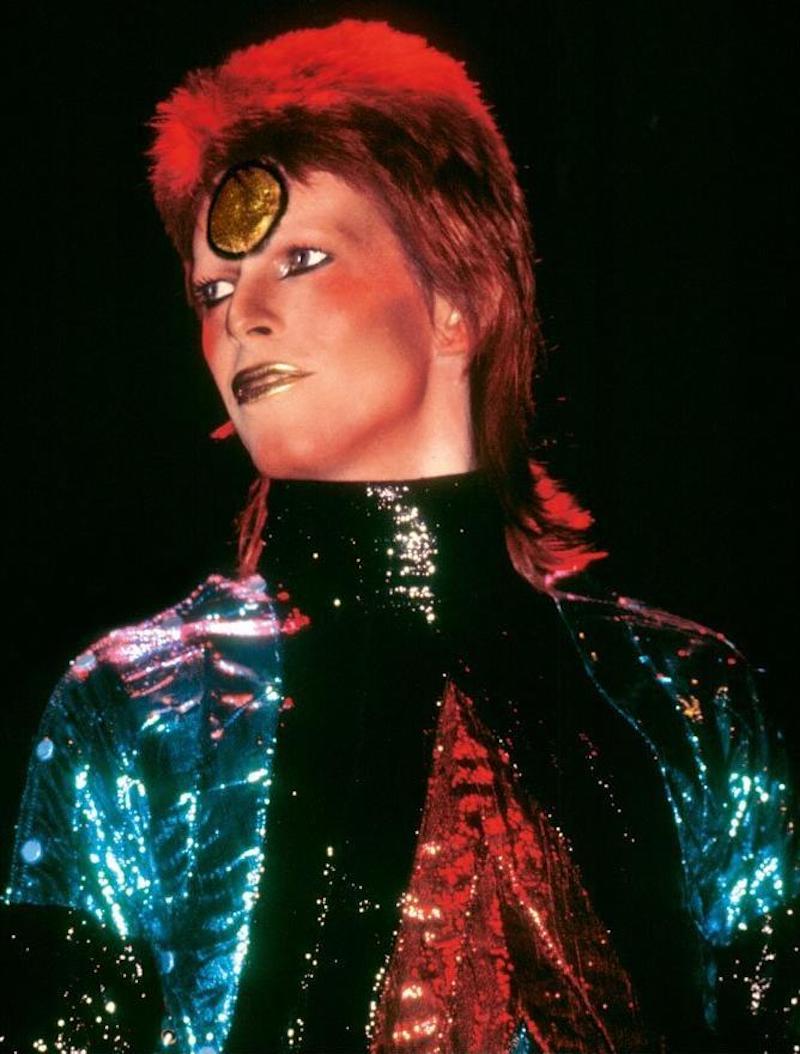

Inspired by a 1920s Bauhaus ballet costume by Oskar Schlemmer, you may know it from this 1973 image. Who could forget that vinyl jumpsuit?

Yamamoto said that when he designed Bowie clothes, he approached it as if he were designing womenswear (you’ll notice no front zips on the pieces) where he got his start. “Today, lesbian and gay people today are gaining more rights and acceptance,” he later said about the pioneering nature of the fashions, “but when I was working, that community did not have the same rights. I found David’s aesthetic and interest in transcending gender boundaries shockingly beautiful.”

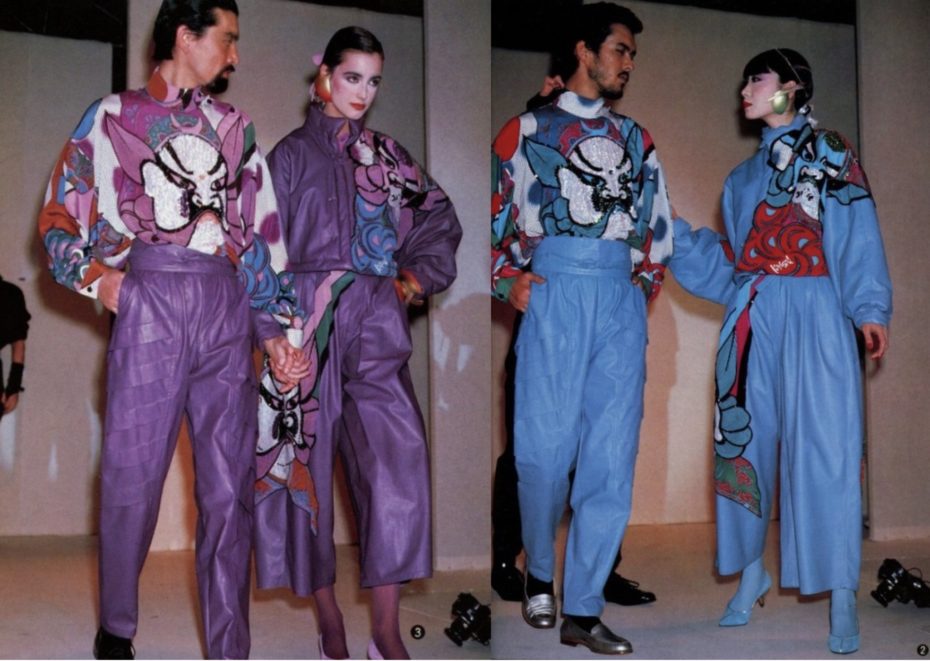

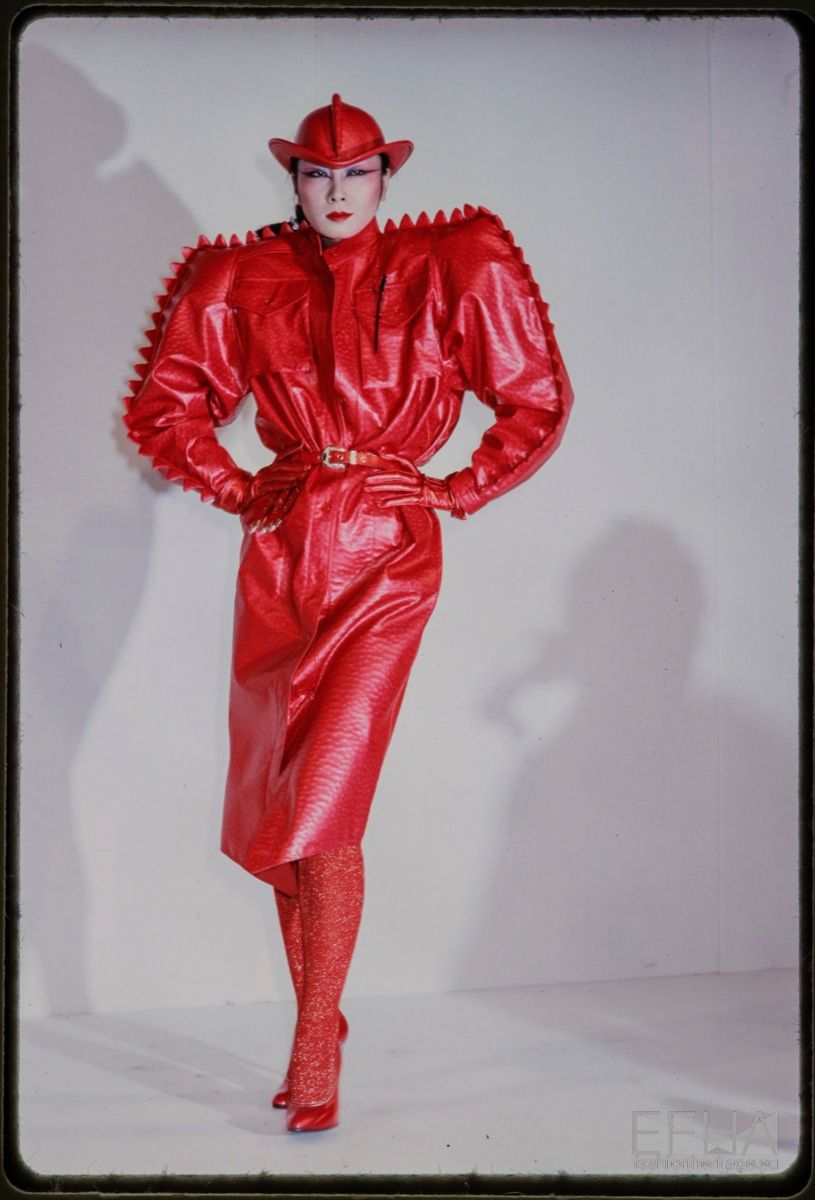

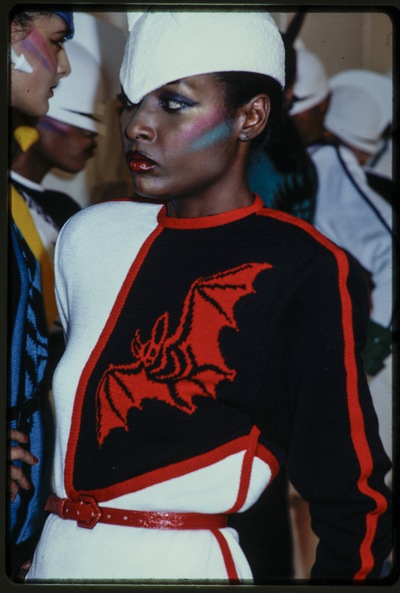

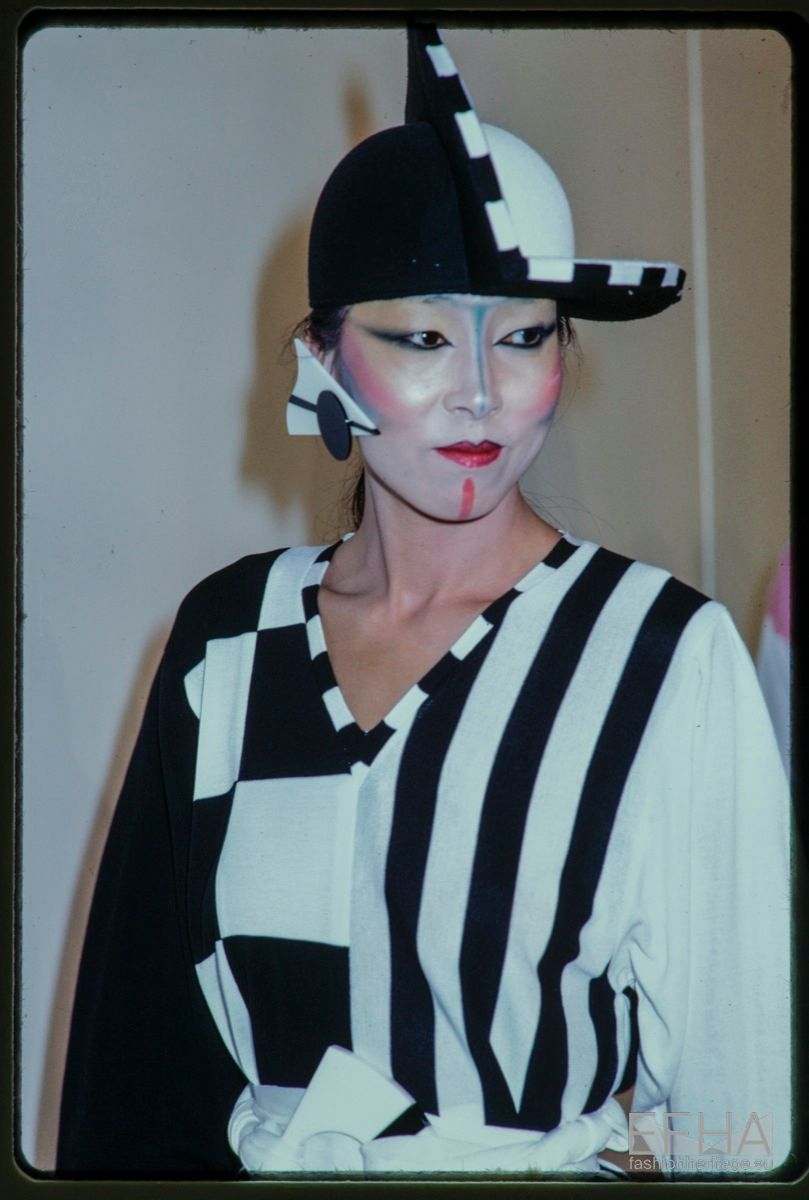

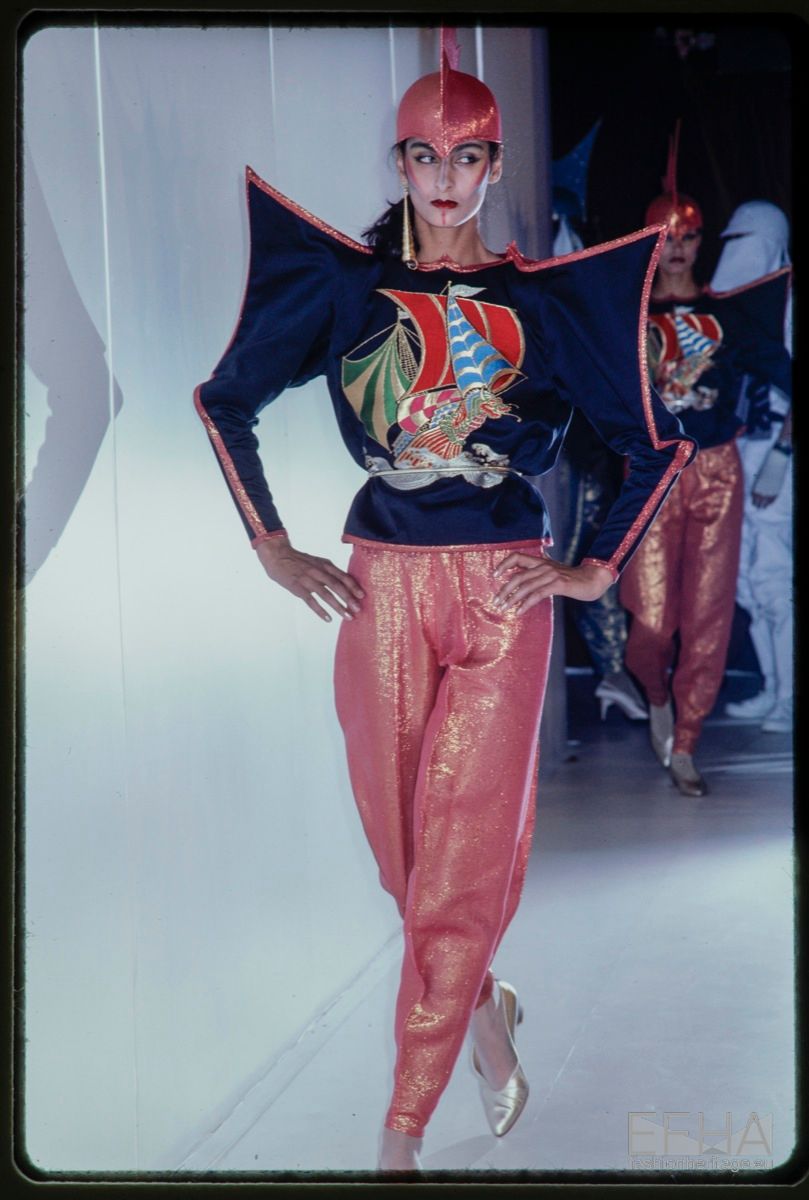

In 1971, Yamamoto founded his own company in Tokyo and hit the ground running; that same year he not only debuted his work at London Fashion Week, but got a deal with a hip department United States department store, Hess, to carry his collection. Aside from their deeply colourful, architectural nature, the clothes were inspired by Kabuki theatre, art from Japan’s Momoyama period (1500s-1600s), and the concept of basara, meaning “extravagance, eccentricity, and excess.”

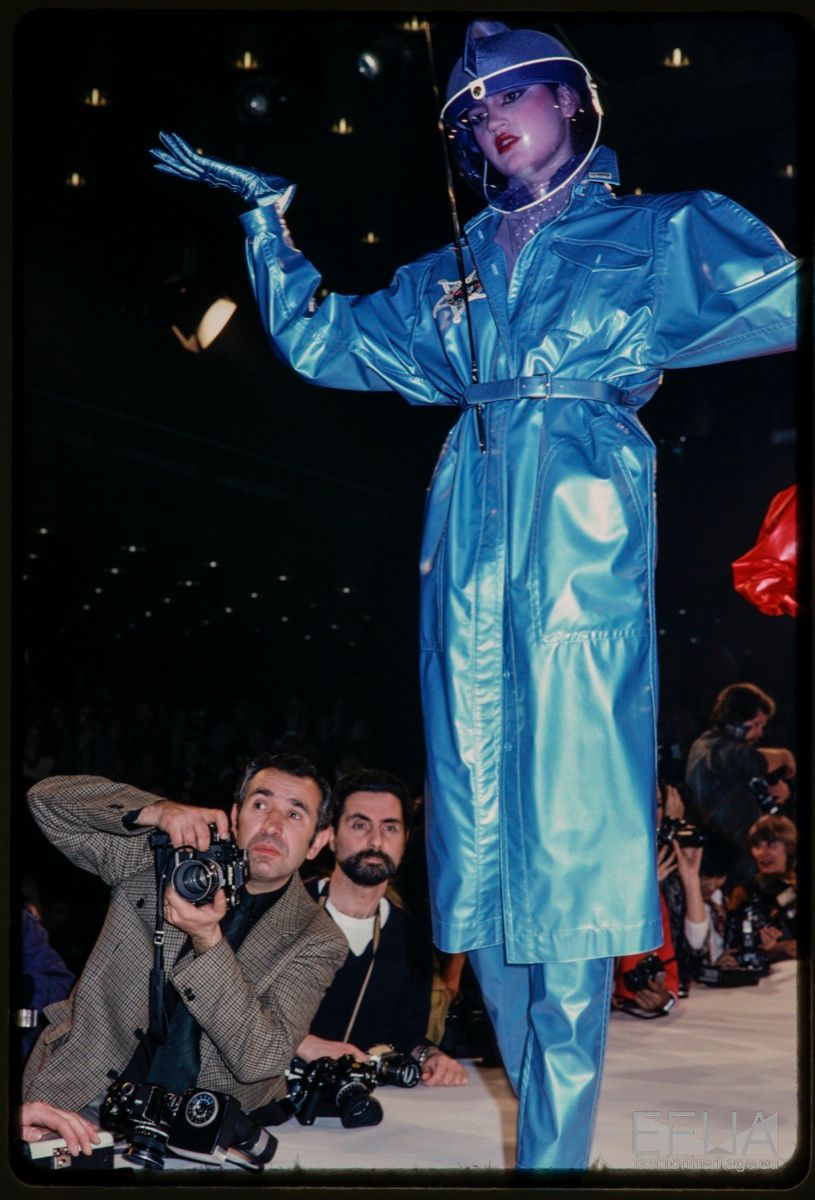

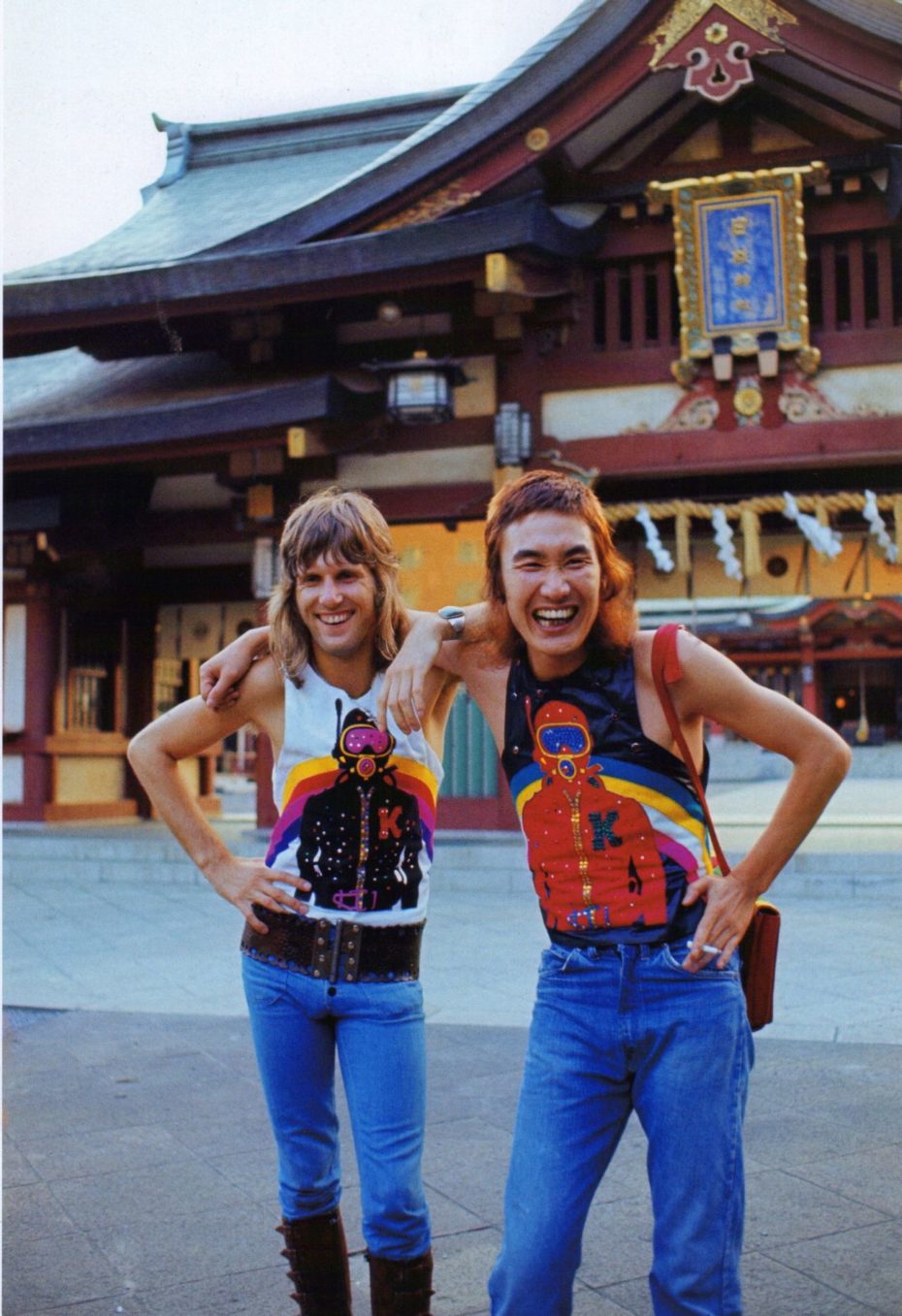

Something else was stirring in Japan. The 1960s-80s was a time of huge economic growth, and “not only a time of political activism and rebellion against the establishment,” as Japan Times explains in a 2012 article on that period’s legacy, “but one that saw Japan looking to the future with the introduction of new technology at the Osaka Expo.” Yamamoto’s designs were right on the money as an irresistible, Sci-Fi homage to traditional Japanese culture.

“Kansai chose his own models and wanted the sessions to be ethnically mixed (and rightly so),” reflects celebrated photographer Clive Arrowsmith, “this was very much the exception for the time.” A look back at his runway shows is a breath of fresh air in that and so many other respects; it shows an environment that both doesn’t take itself too seriously, and commits to the kind of inclusivity we need to see so much more of in fashion, almost half-a-century later. Pull up a chair.

His shows continued to unfold as spectacular events in London, Paris, and New York, drawing crowds of thousands and very much anticipating the level of entertainment and whimsy we now expect from Fashion Week runway shows from brands like Chanel and Gucci. They were filled with acrobatics, nods to Kabuki theatre, and so much audience enthusiasm that he called them, “Super Shows.”

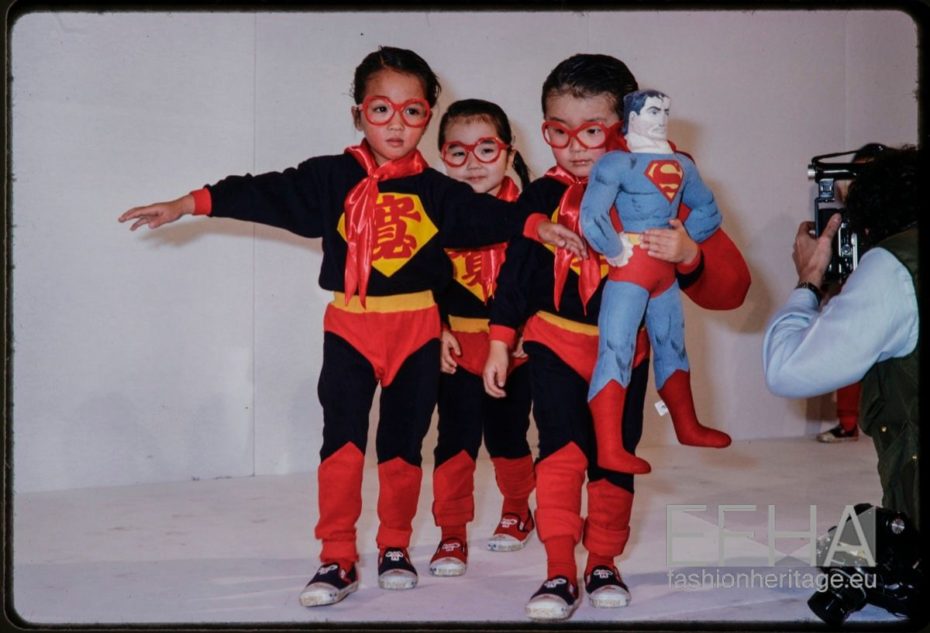

Even kids got in on the fun:

That’s Yamomoto on the left in white, helping a kid wave for a photograph.

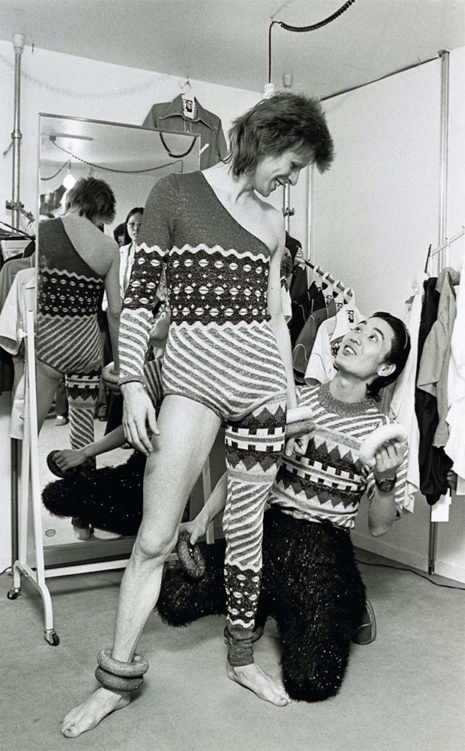

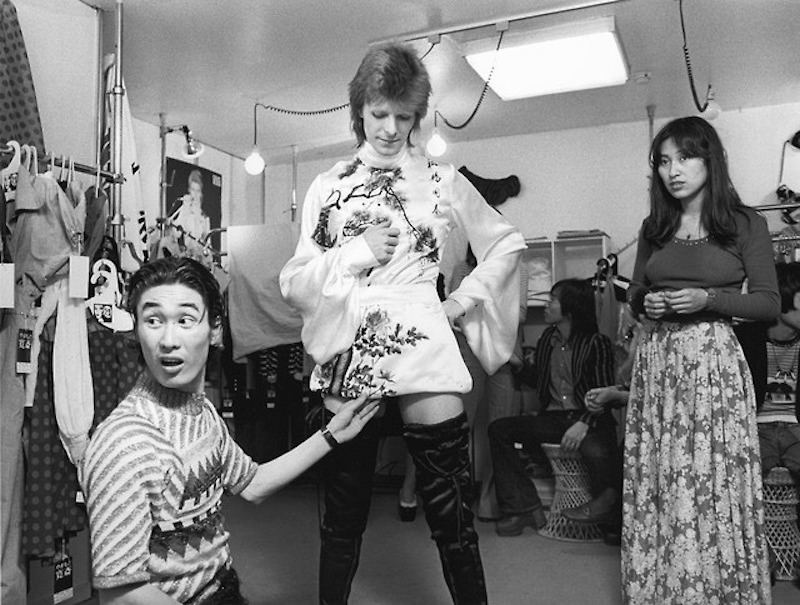

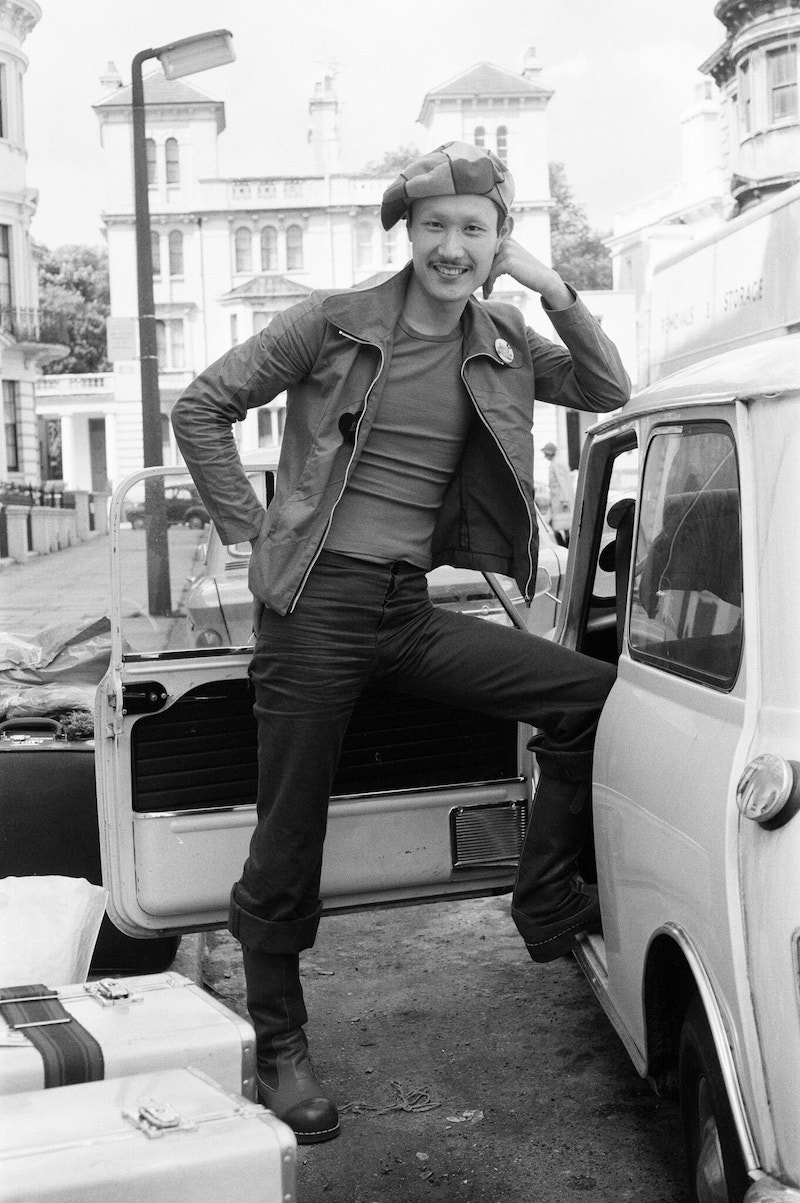

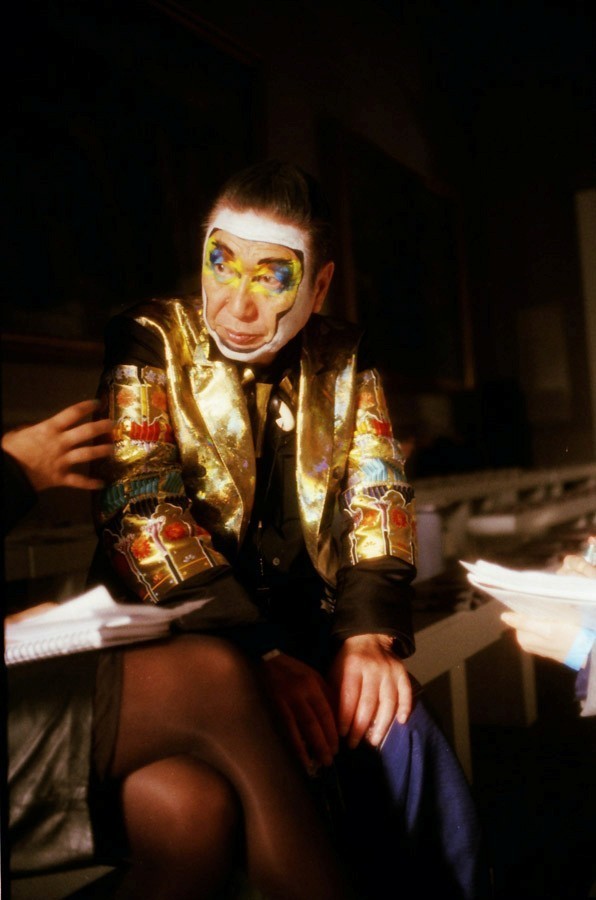

Bowie had been smitten with Yamamoto’s design ever since his ’71 womenswear debut in London, which drew the crème de la crème of pop culture. Here he is in the afterglow of that show in London:

Funnily enough, Yamamoto only clocked Bowie a few years later. At the insistence of Bowie’s producer, he flew to New York’s Radio City Music Hall to see Bowie perform in one of his designs, and it was during that encounter – in which Bowie “introduced” himself by crawling atop a giant disco ball – that the designer knew this was creative kismit.

“I think David felt that the energy,” he later said, “[my work] contributed to his own energy. He knew that when he wore my clothing onstage, he could elicit a strong reaction from the audience.” The fruits of that friendship gave us the sartorial fantasy of his 1973 Ziggy Stardust tour.

“The Ziggy hairstyle was taken lock, stock and barrel from a Kansai (Yamamoto) display in Harpers,” said Bowie, “He was using a kabuki lion’s wig on his models which was brilliant red. And I thought it was the most dynamic colour, so we tried to get mine as near as possible…I got it to stand up with lots of blow-drying and this dreadful, early lacquer.”

Yamomot’s final collection was in 1992, but he went on to collaborate with various designers, and licensed his name to everything from a Skyliner train to tableware, working with designers like Anna Sui, Louis Vuitton, and more. Perhaps that’s why it feels like he was more unsung than the “Big 3” designers of the 1980s and ’90s; not only was his take on Japanese design arguably more theatrical, but he began favouring event production over fashion design. At their pique, his Super Shows travelled to places like Vietnam, India, Russia – the latter of which was held in Moscow’s Red Square to a crowd of 120,000 people.

Yamomoto also went on to design outfits for Elton John and Stevie Wonder, and remained close friends with Bowie until the superstar passed away in 2015. According to Yamomoto, they had been planning a Super Show together.

Yamomoto has been gaining more mainstream attention in recent years, notably through the travelling David Bowie Is exhibit that ran from 2013-18. If you ask us, his influence lives on not only through the praise of designers like the “Big 3,” and style titans like Jean Paul Gaultier to Hedi Slimane, but in the stylish streets of Tokyo where fashion is – and has been – winning for ages on the backs of the everyday weirdos. So cheers, Mr. Yamomoto. We’ll miss you and your vision.