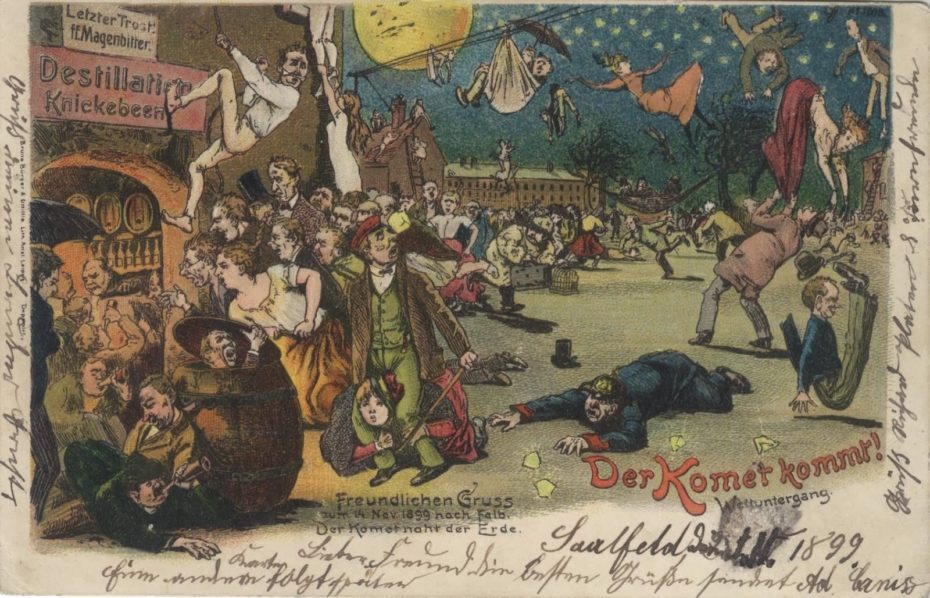

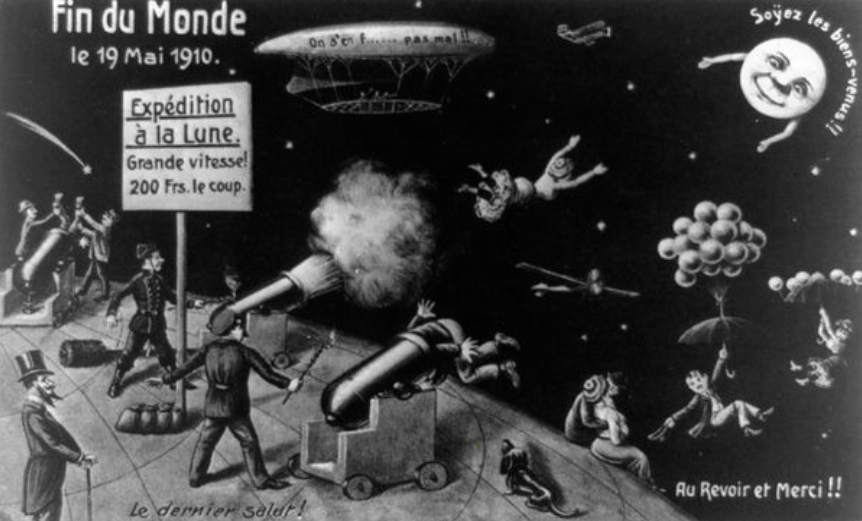

Ah, to have planned for a comet apocalypse in the Belle Epoque! Looks like a wild time, according to all the 19th and 20th century postcards with folks soaring through the skies, bum over noggin, towards a starry death. Out of all the (ultimately) anti-climactic close comet calls, the 1910 approach of Halley’s Comet takes the cake. Not only did it lead to the first ever photograph of a comet, and the actual gathering of “spectroscopic ” data, but because the anticipation of its arrival caused a media frenzy, stores started selling “anti-comet pills.” Papers put out ads for escape submarine rentals. One cult considered sacrificing a virgin. Just how did it all get so crazy?

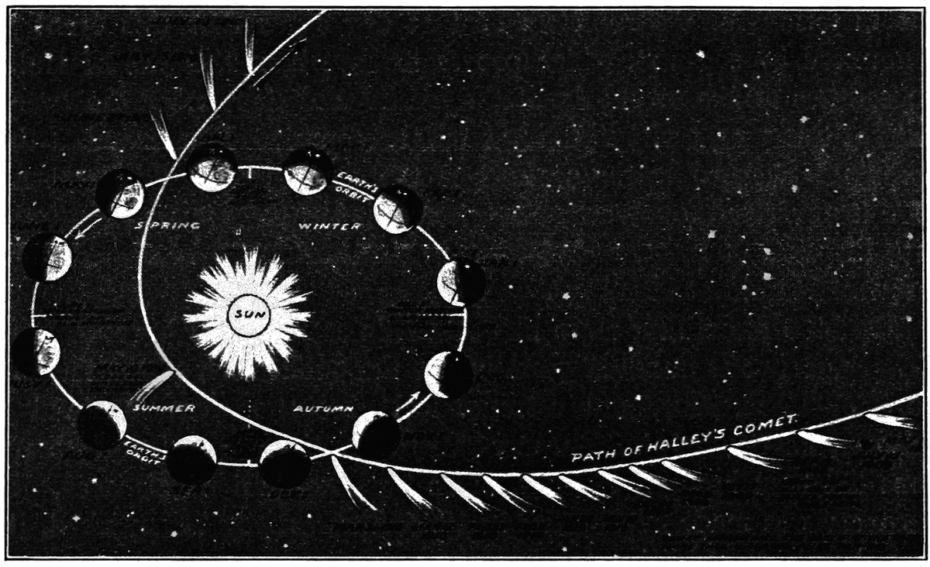

It’s hard for us science laypeople to fathom the workings of space, let alone its errant pebbles. Although, Halley’s never been just a random fly bye event; by 1705, its orbital period of 75 or so years was confirmed by the English astronomer, Edmond Halley, bringing us both the comet’s eponymous name and a new tradition: once, maybe even twice in a lifetime, the comet’s 24-million-mile long tail would become visible to the naked eye. Fun fact: he might not have had his breakthrough, if he hadn’t consulted a friend and fellow scholar named Isaac Newton.

But people started to wonder – were there consequences of such seemingly close contact? One account of its 1835 passing describes a “vapour trail” in the sky, immortalised below in watercolour…

When Halley was next slated to return, it was at the beginning of a new century in 1910, when advancements in media and technology had radically accelerated the circulation of people and ideas, and major breakthroughs were being made in the automobile and radio industries; the world had seen the first airplanes and photographs – including the photographs of astronomical objects. That meant it was finally, hopefully, the moment to capture an image of the comet when it neared earth in one of its shortest return cycles yet, a mere 74 years. It had one man in particular, a French scientist named Camille Flammarion, feeling rather worried…

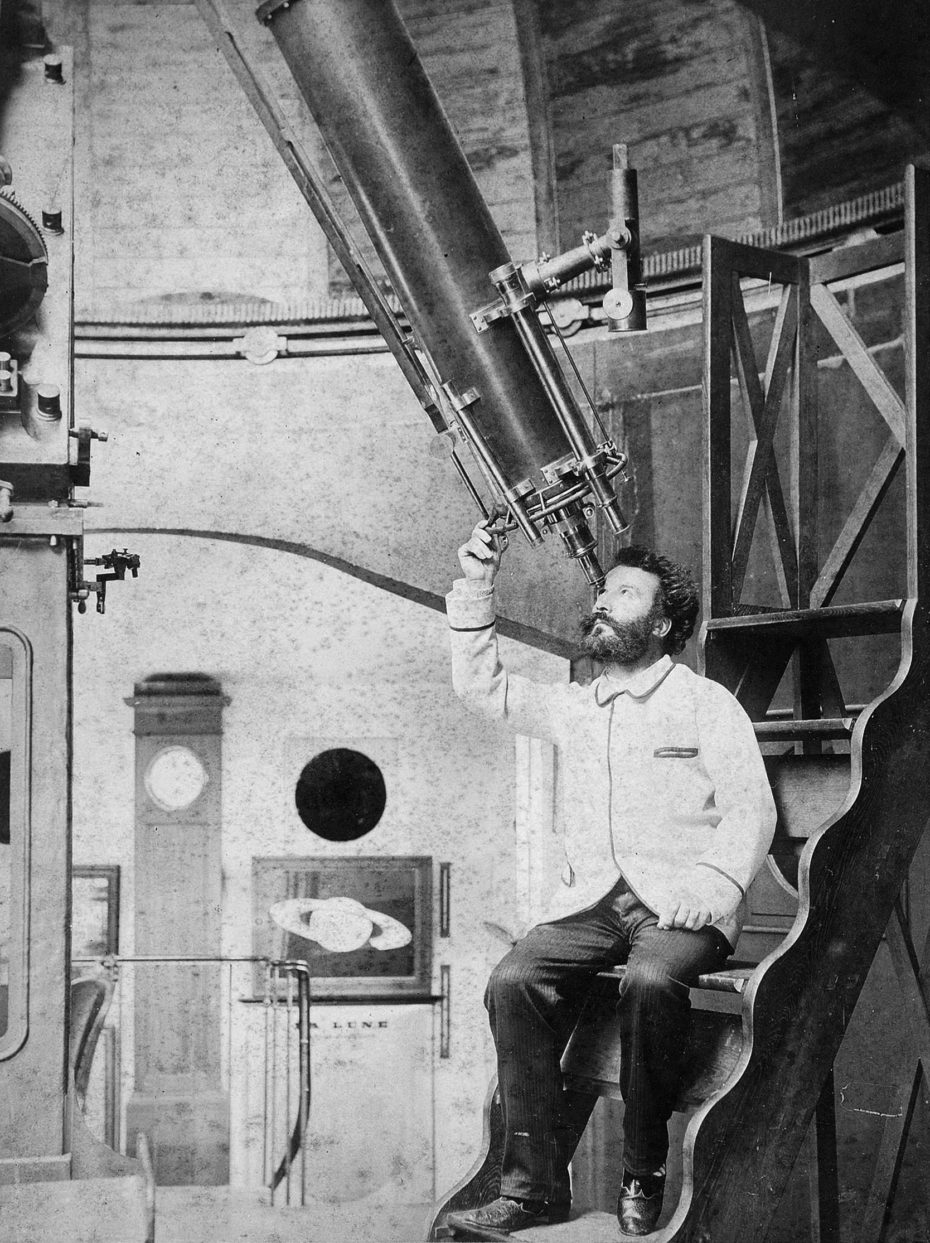

Flammarion was a prominent, and above all colourful presence in the astronomy scene. He ran the journal L’Astronomie, as well as his own private, castle-like observatory in Juvisy-sur-Org, France, which you can still visit today as the “Flammarion Observatory.” It’s about a 45 minute drive south of Paris, and only 15 minutes by public transport. Check it out in its heyday:

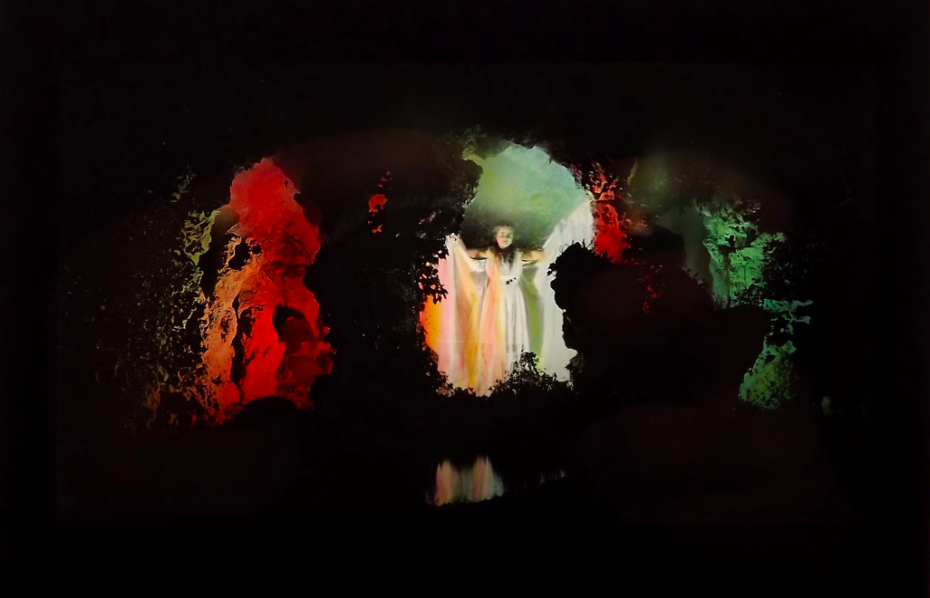

We’ll try not to get too off-track in drooling over Flammarion’s eccentric observatory, but it really was a unique place. Not only did he have an observation tower, but an impressive library, garden, and grotto where he held avant garde performances:

As an author, he penned both scientific essays and science fiction with a talent for poetic turns of a phrase. Readers loved it; critics tended to roll their eyes at his tendency for sensationalism. “This end of the world will occur without noise, without revolution, without cataclysm,” he wrote in L’atmosphère : météorologie populaire in 1888, “Just as a tree loses leaves in the autumn wind, so the earth will see in succession the falling and perishing of all its children, and in this eternal winter, which will envelop it from then on, she can no longer hope for either a new sun or a new spring. She will purge herself of the history of the worlds.” Yikes.

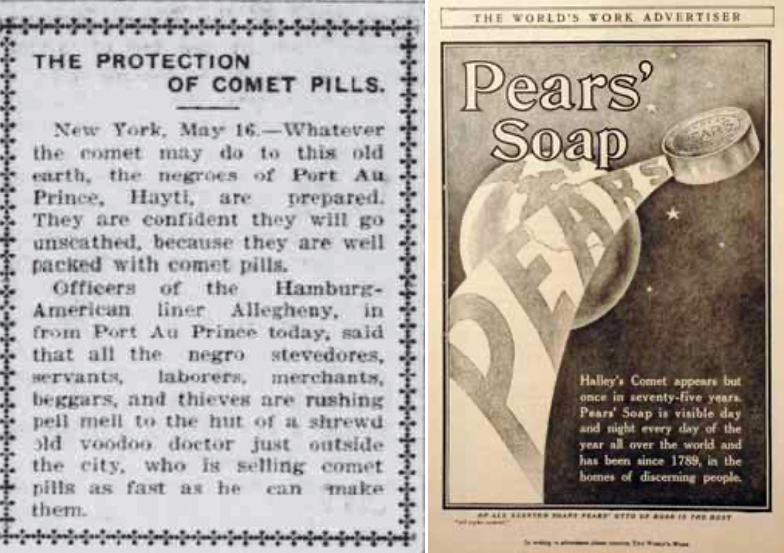

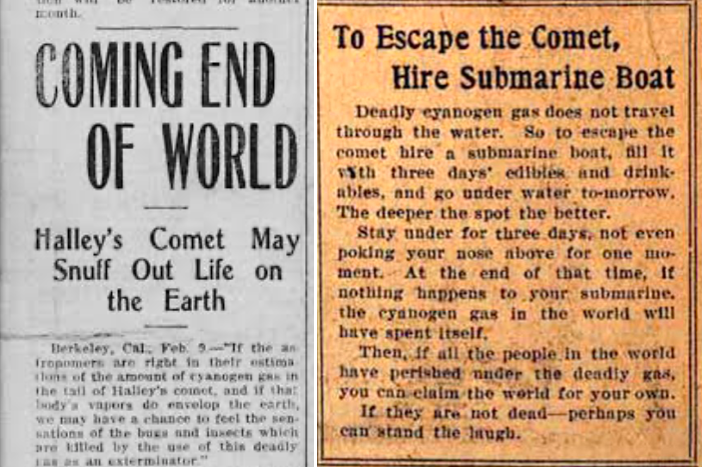

The incoming of Halley’s comet, he said, contained a poisonous cyanogen gas that “would impregnate the atmosphere and possibly snuff out all life on the planet.” When The New York Times ran a story on his assertion, the fear amplified on a global scale in the tabloids. One science writer, Matt Simon, said folks were so frightened, they began sealing up the keyholes of their houses to “keep the poison out of their homes.”

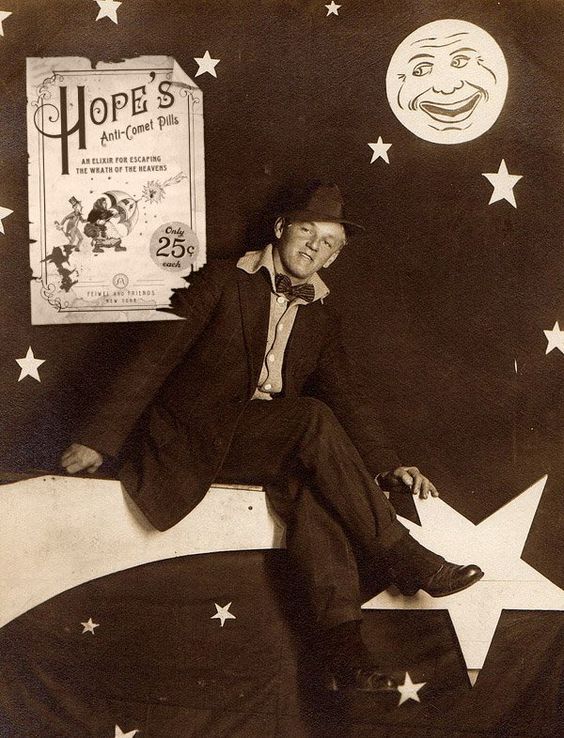

The “Sacred Followers” religious group in Oklahoma was reportedly planning on sacrificing a virgin to ward off the disaster, but was stopped by police. Comet pills, comet shelters, comet soap, and even submarine rentals became the norm for doomsday preppers.

Some families went on full-on lockdown, buying comet masks while other sipped on “Comet whisky.” It was a weird time – somewhere between genuine fear, and a kind of collective, giddy anticipation of humanity’s swan song. Advertisers in booze and tobacco took note…

Even fashion took a turn. It wasn’t uncommon to find both amateur and professional-grade comet buttons, broaches and jewellery.

It’s funny, some of the designs might not strike you as comet-inspired. But once you know, you know, and are ready to take to the online vintage shops with keywords like “1910 comet” and “Halley” to find some pretty cool gems.

It was as if the business of Halley, and the scope of its cultural possibilities, had superseded its reality. There was a certain adoration for this comet in particular than outweighed others, as comets were certainly nothing new at this point. In 1910, the New York Times reported on a sighting of another comet, saying, “the comet some clear-sighted folks say they have seen near the western horizon of late is not Halley’s comet, but an unidentified butter-in from space, now called for convenience, ‘A, 1910,’ which is as good a name as any for a comet without a history.” Ouch.

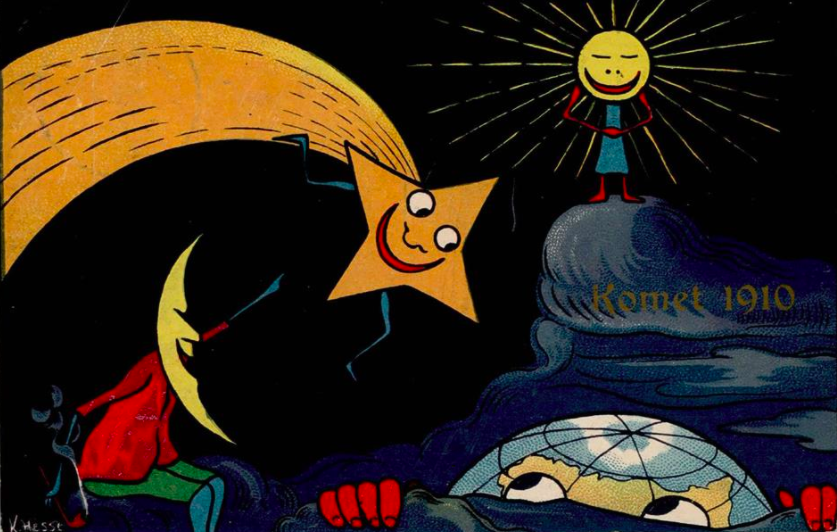

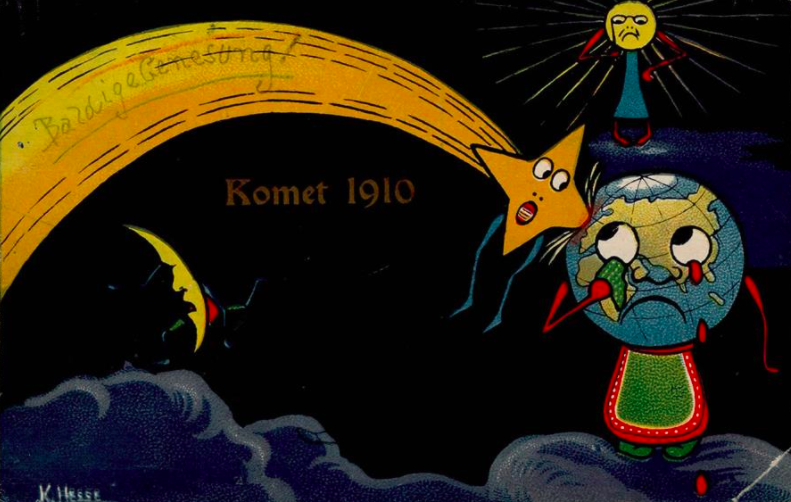

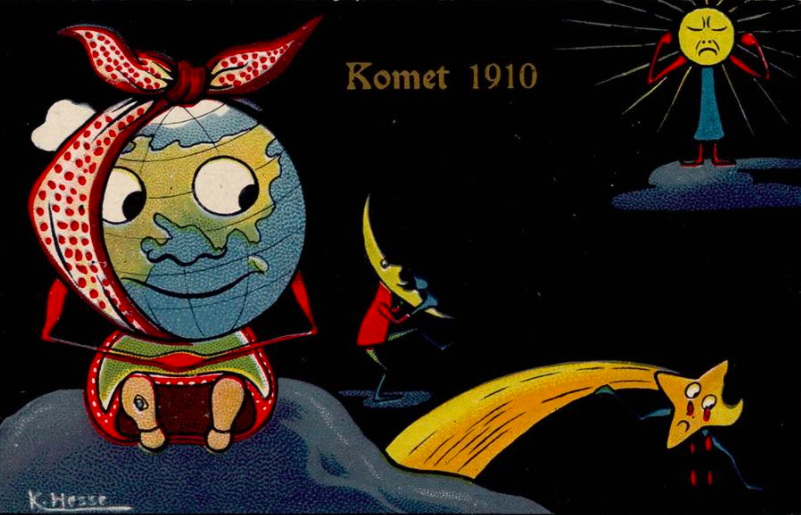

Halley was, quite literally, an international poster-child for galactic chaos:

Then, the moment came: on May 19th, 1910, our little blue planet actually passed through the tail of the comet, at a relatively close approach of 0.15 AU. It was a rare occurrence – and that’s saying a lot for a comet has been going on this cycle for potentially some 200,000 years. Prior, the closest approach we have on record was in 837, at a distance of 0.04 astronomical units (AU; 6 million km [3.7 million miles]). Finally, in 1910, we got it on camera:

There were no mass plagues, no impossible bending of bodies upwards towards space, or any of the asphyxiating deaths the gossip rags had predicted. But some folks believed there were some very real consequences.

“I came in with Halley’s comet in 1835,” Mark Twain famously wrote in 1909, decreeing that he fully expected “to go out with it in 1910,” which, to his credit, he did. Was Twain’s death a feat of willpower, coincidence, or fate? Who knows. But it was one in a series of events that used the comet as a launching pad for a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. Some cited the event as the cause of death of King Edward VII. The civil unrest surrounding the comet even helped spark China’s Xinhai Revolution in 1911, which effectively ended the last dynasty.

The truth is, that level of drama nothing new for this comet. Halley has been stirring the pot for ages…

As aforementioned, scientists estimate that Halley has probably been in its current orbit for up to 200,000 years. That means people have been scratching their heads over this thing for a while, as evidenced by a 240 BC recording from Chinese astronomers. There’s France’s iconic 11th century treasure, the Bayeux Tapestry too, on which our Halley makes a suprise cameo…

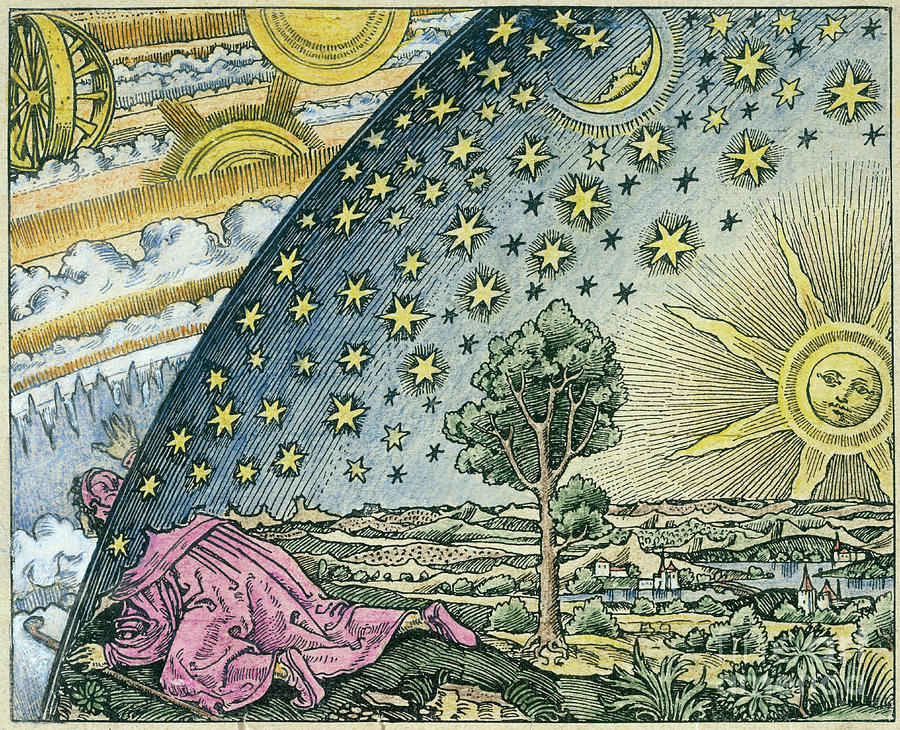

Pior to Mr. Halley’s 18th century discovery of its cycle, many cultures thought the comet might be some godly or mystical force. Halley has even been a ye olde model for the Star of Bethlehem, as seen in this 14th century painting. By the way, ancient and medieval depictions of comets are pretty wild – almost alien…

In the 11th century, William the Conqueror chose to see the comet as a positive sign from the heavens – a kind of cosmic green-light to carry out the Norman invasion of the British Isles. In that vein, comets in general were believed by historians to have foreshadowed Atilla the Hun’s invasion of Gaul, the fall of Jerusalem, and both the birth and death Julius Caesar.

But not everyone saw Halley as a blessing. When the comet was spotted by France’s King Louis I in the 9th century, he saw it as a celestial slap on the wrist to build more churches. In the 15th century, a humanist scholar named Bartolomeo Platina wrote about the comet’s passing with godly fear. “A hairy and fiery star,” he wrote, “having then made its appearance for several days, the mathematicians declared that there would follow grievous pestilence, dearth and some great calamity.”

The anxiety of the 1910 freak-out wasn’t anything new. In a way, it probably felt like the boiling point of centuries of wonder and uncertainty. It’s when we add in the social and technological conditions under which it unfolded, that we see its evolution; this wasn’t just a communal panic or fantasy, but one that could be vigorously commodified, marketed, and photographed. It continued when Halley made its last appearance in the 1980s, albeit with no apocalyptic fear:

Makes you wonder what conditions we’ll have for Halley’s next appearance. Thoughts? Share your theories in our comments box below, and save the date for July 28, 2061…

Learn more about visiting the Flammarion Observatory here.