We don’t really need a reminder of just how bad smoking is for us. Bad for our physical health, the environment, and cringe-worthy on so many social justice levels. Why is it then, that women always looked so damn cool smoking their cigarettes in vintage photographs? There’s a complicated blend between our lifetime exposure to big tobacco marketing, and the very real role smoking had as a signifier for the independent woman, which has prompted us to take a closer look at the radical history of women smoking…

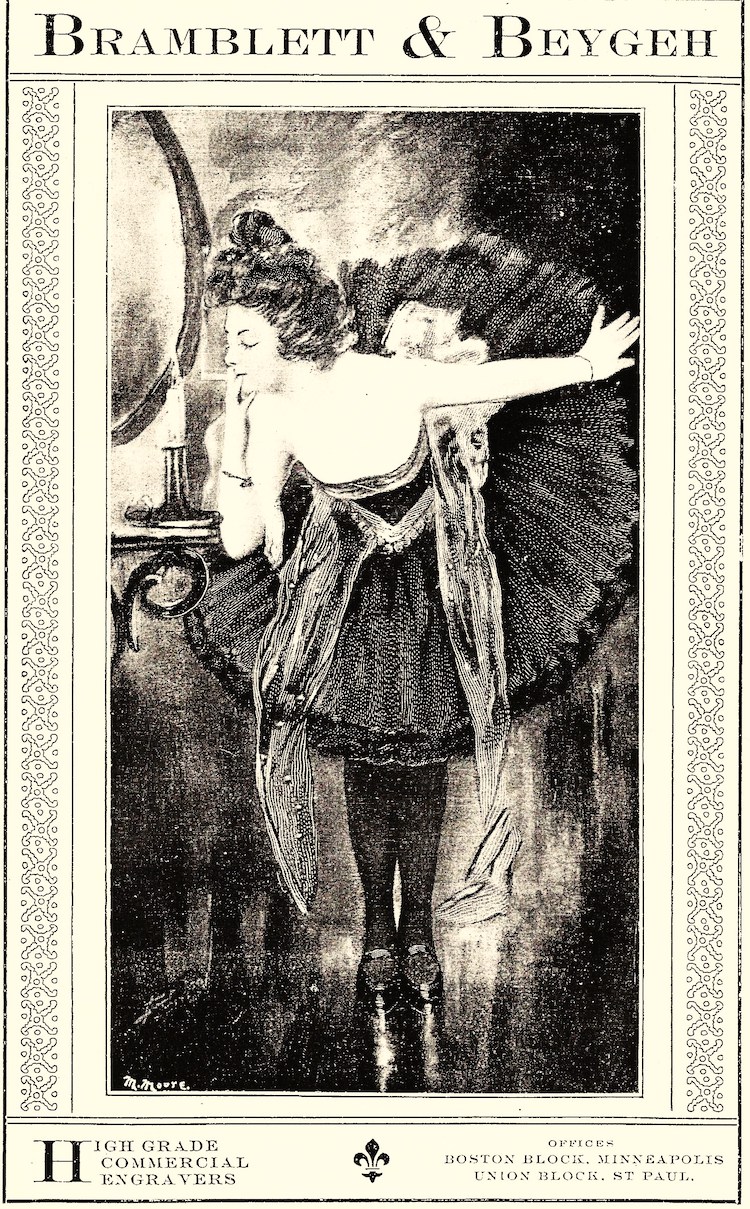

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the market for vices like tobacco and booze made little space for women (the purest and most delicate of creatures, of course). So pure, they’d get fined for smoking in public. In 1908 New York City rendered women’s smoking completely illegal for two weeks. An ad like the one below, trying to tap into a pseudo-bohemian, cultured consumer in 1901, would’ve been rather scandalous at the time.

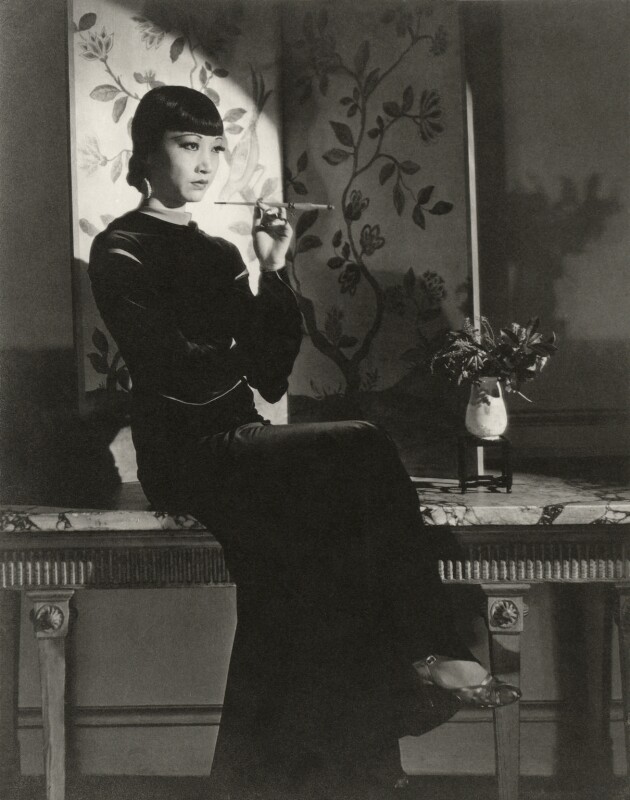

Cigarettes were gendered as masculine by advertisers, or else working class and “alternative” or “bohemian” at best; evocative of Paris, for example, where the bohemian scene was famously more inclusive than the United States, and the terrace cafés took much kinder to ladies lighting up…

Legend has it, the French diva Sarah Bernhardt would cause a scandal every time she smoked inside a hotel in the United States, and staff would have to bring a folding screen to “shield” her from other guests. Women’s suffrage, too, embraced smoking as a symbolic form of gender role dissent and a sign of independence. So in its own way, the vintage lady’s decision to smoke was more than risqué. It was straight up punk.

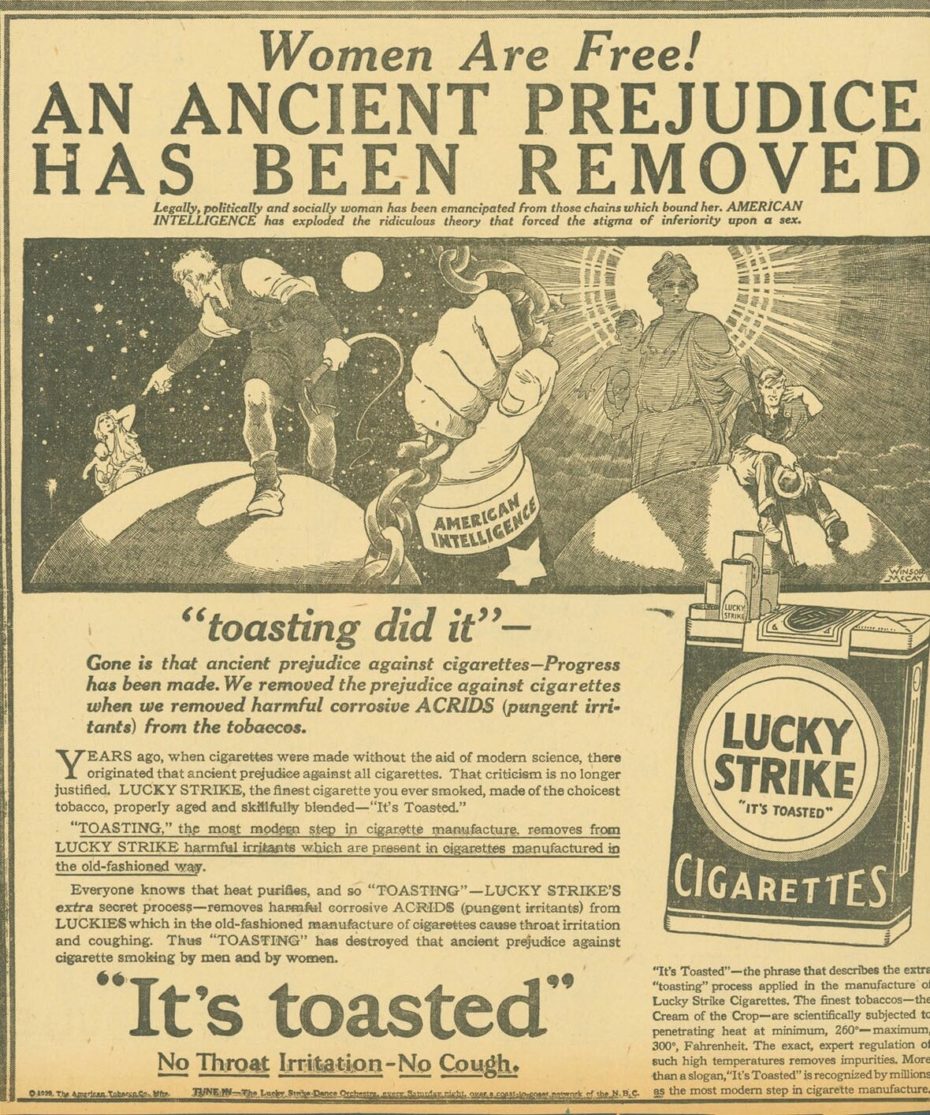

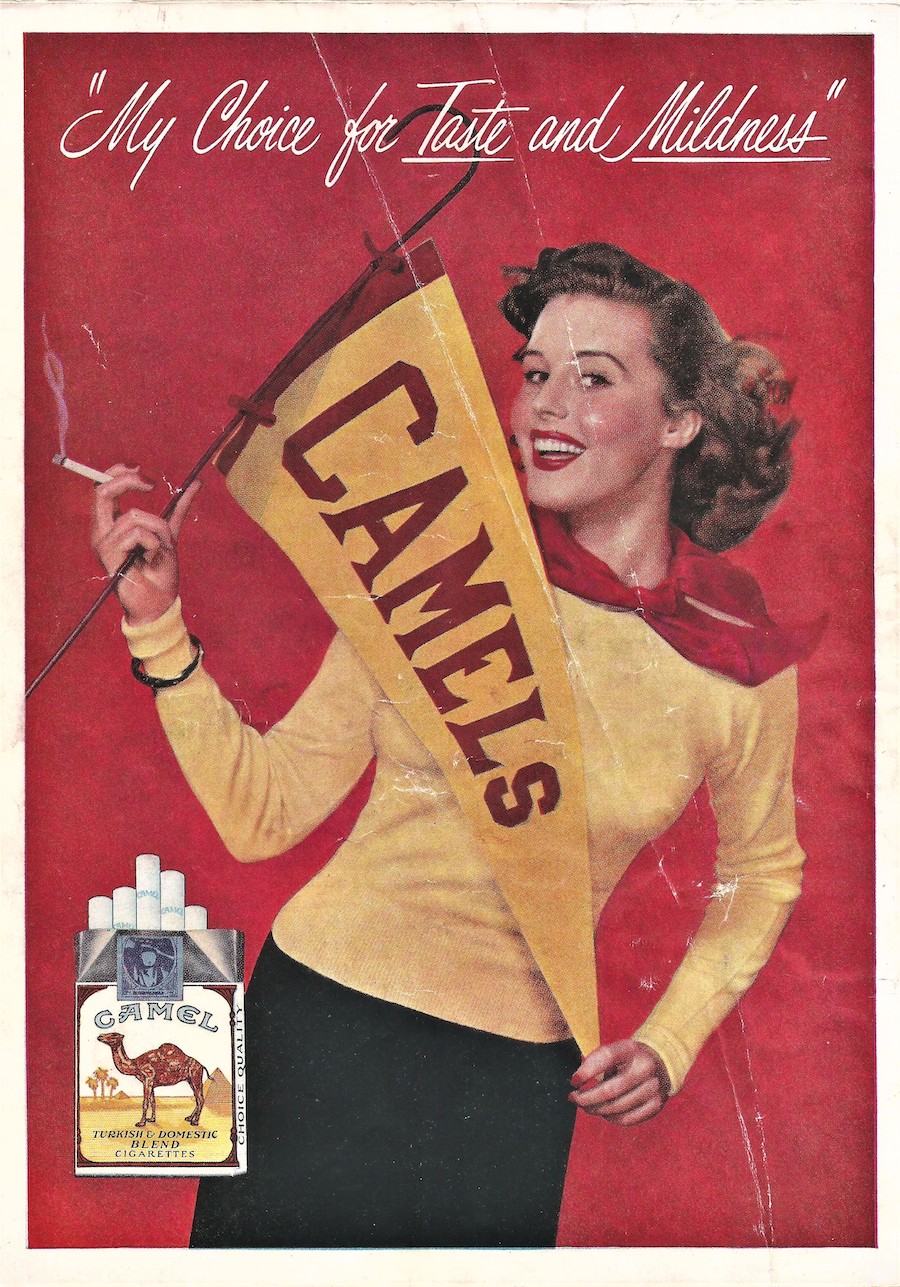

That’s how cigarettes became an accidental symbol for First Wave Feminism, and when advertisers jumped at the opportunity to tap into this previously ignored demographic, touting their cigarettes as “Freedom Torches!” in ads that encouraged women to smoke.

It was actually Sigmund Freud’s nephew, Edward Bernays (1891-1995), who led the marketing strategies to encourage women-targeted tobacco items. After successfully creating a slew of pro-war propaganda for the U.S. Government’s Committee on Public Information (CPI) in WWI, the American Tobacco Company tracked him down to start cooking up ways to appeal to an increasingly “liberated” demographic: women. One of Bernays’ biggest PR moves was encouraging women to smoke their Torches of Freedom during a big NYC Easter Day Parade in 1929.

“The tobacco industry realized that half of its potential customers were not even considering using cigarettes,” Robert Jackler, a tobacco advertising researcher at Stanford University, told Business Insider in an article in February, 2020, “The industry actually began engineering ways of encouraging women to be willing to smoke in public.” They even hired the non-smoking Amelia Earhart to lend her image to a campaign for Lucky Strike cigarettes. (Is it just us, or can you tell she’s not that jazzed about it?)

“It’s toasted!” was a common slogan slapped across the ads, declaring a new, smoother experience that was naturally more suitable for women. There were also the cringe-worthy weight loss slogans like, “Reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet” and other claims for maintaining a “slender figure.”

Then Bernays realised something else about Lucky Strikes – these cigarettes were being pushed on women, but not really changed for women. Apparently, he found, they were less likely to buy Lucky Strikes as the red and green packaging clashed with women’s fashions at the time. Big Tobacco honcho George Hill rolled his eyes at Bernays’ insistence to change to neutral packaging after they’d already rolled out the designs. The solution? Change women’s fashion to fit cigarettes. Seriously. Lucky Strike partnered with suffragette Narcissa Cox Vanderlip to host a “Green Ball” for, eherm, “charity” at the Waldorf Astoria. All the elegant society ladies turned up in their finest shades of emerald…

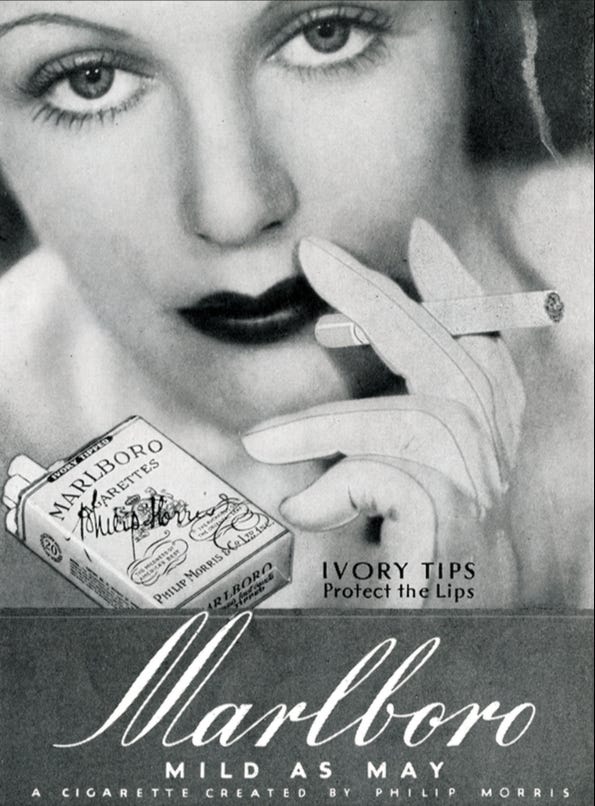

In 1925, the Phillip Morris Company decided to have its hand at making cigarettes for women, and introduced a new brand of smokes that were declared “Mild as May!” as a truly feminine smoking experience. They called them “Marlboros.” That’s right folks, before the Marlboro Man came the Marlboro Dame.

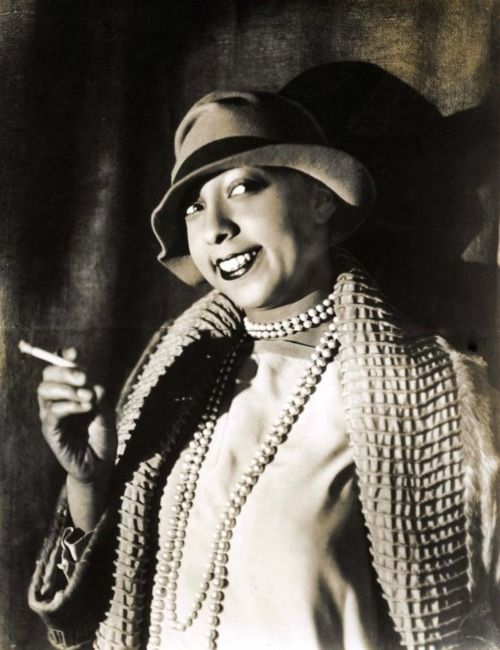

Hollywood also took note, and studio talent sponsorships went underway. “My voice is clear as a bell!” declared actors like Clark Gable, Joan Crawford, and Lauren Bacall – with her trademark, sultry low-octave voice – both on and off screen. Some 200 Golden Age actors puffed their way to the bank, and American Tobacco spent more than $3 million on those sponsorships in 1937-38 alone. The sexiness of the cigarette had been cemented on-screen, and partnership or not, you could always expect to find a stylish siren smoking in a “talkie”

Then came WWII, and the shifting roles of women in more manual jobs. Big tobacco wasn’t just tossing their smokes into crowds of soldiers like confetti (true story), but tailoring its ads to these newly working ladies that oozed patriotism.

It’s funny. We tend to look at tobacco’s beginnings in reference to marketing and capitalism, when at its core the plant is considered a sacred tool. The earliest art we have of tobacco use dates to pre-Columbian civilisations that smoked tobacco for ritual and shamanistic purposes.

Florentine Codex, 16th century

Like so many things, it was taken by Europeans and used along with opium, tea, and coffee for medicinal and recreational purposes; first it arrived in Spain, then France, and finally England.

There were some 20th century health specialists who raised an eyebrow about the potential health effects of cigarettes, but they were shrugged off for the sake of profit, and the fact that for a while there, the number of tobacco-caused lung cancer cases just weren’t that high. “Actually, it wasn’t even until cigarettes were mass produced and popularized by manufacturers in the first part of the 20th century that there was cause for alarm,” says the American Cancer Society, “New technology allowed cigarettes to be produced on a large scale. Cigarette smoking increased rapidly through the 1950s, becoming much more widespread.” Apparently, per capita cigarette use went from 54 per year in 1900, to some 4,345 per year in 1963. Women made up 33% of smokers in the United States by 1965, with ads promoting a head-splitting dual-vision of the increasingly independent woman, albeit one who should still watch her figure.

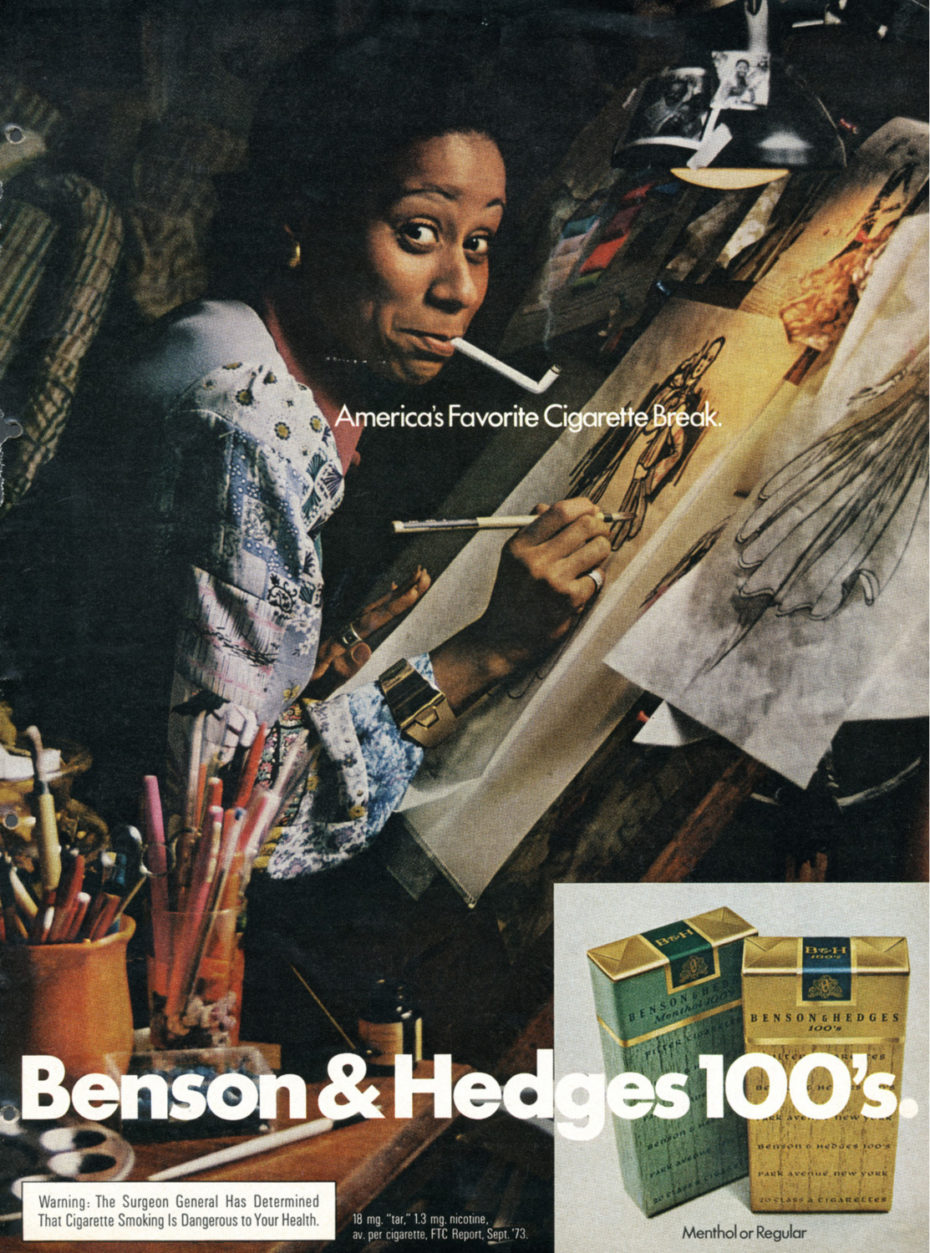

Cigarette companies were also among the first to work with Black magazines to advertise their product, and once the barriers were reluctantly broken, tobacco giants began aggressively targeting Black Americans (who were generally smoking far less than white Americans at the time).

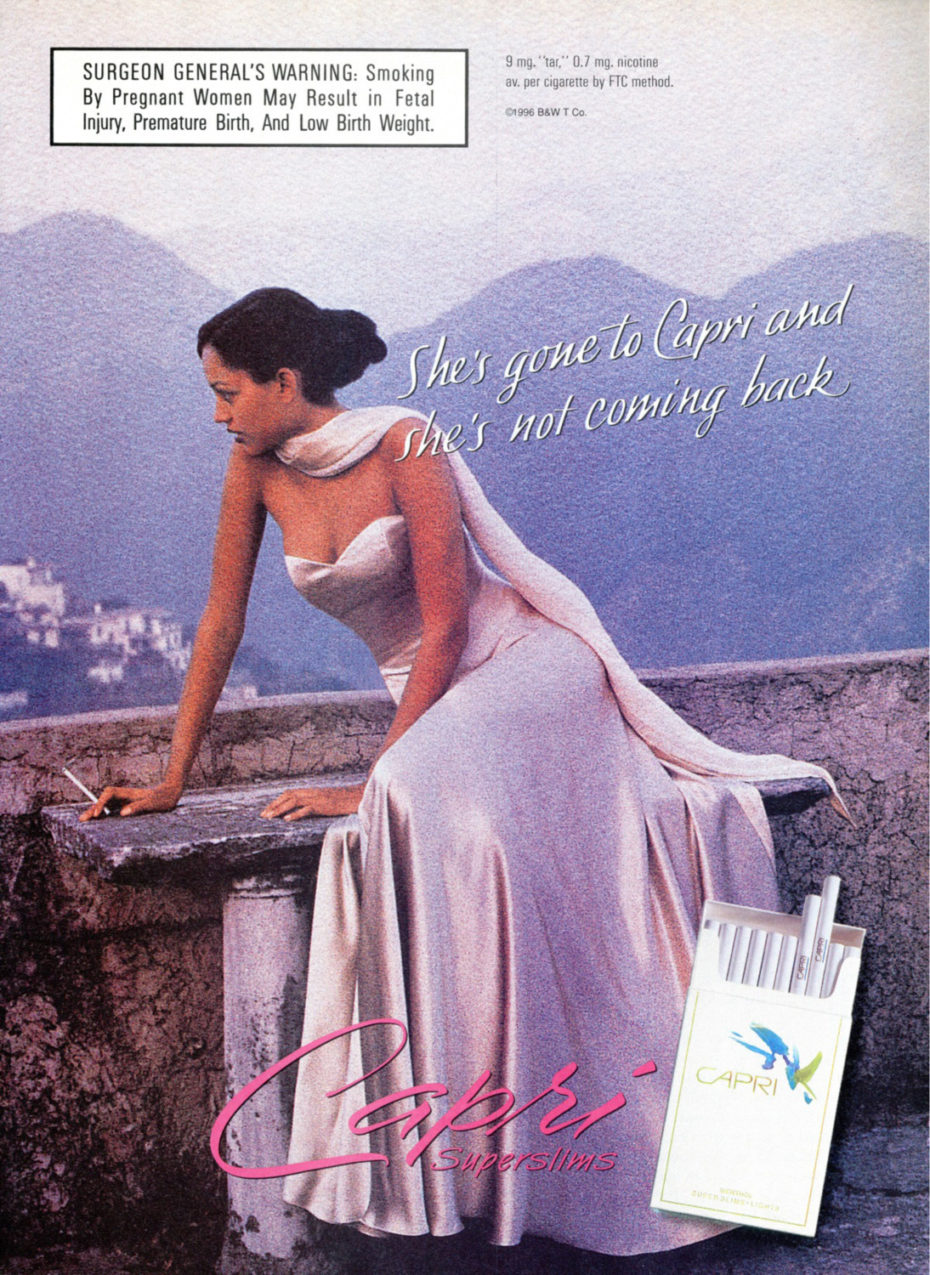

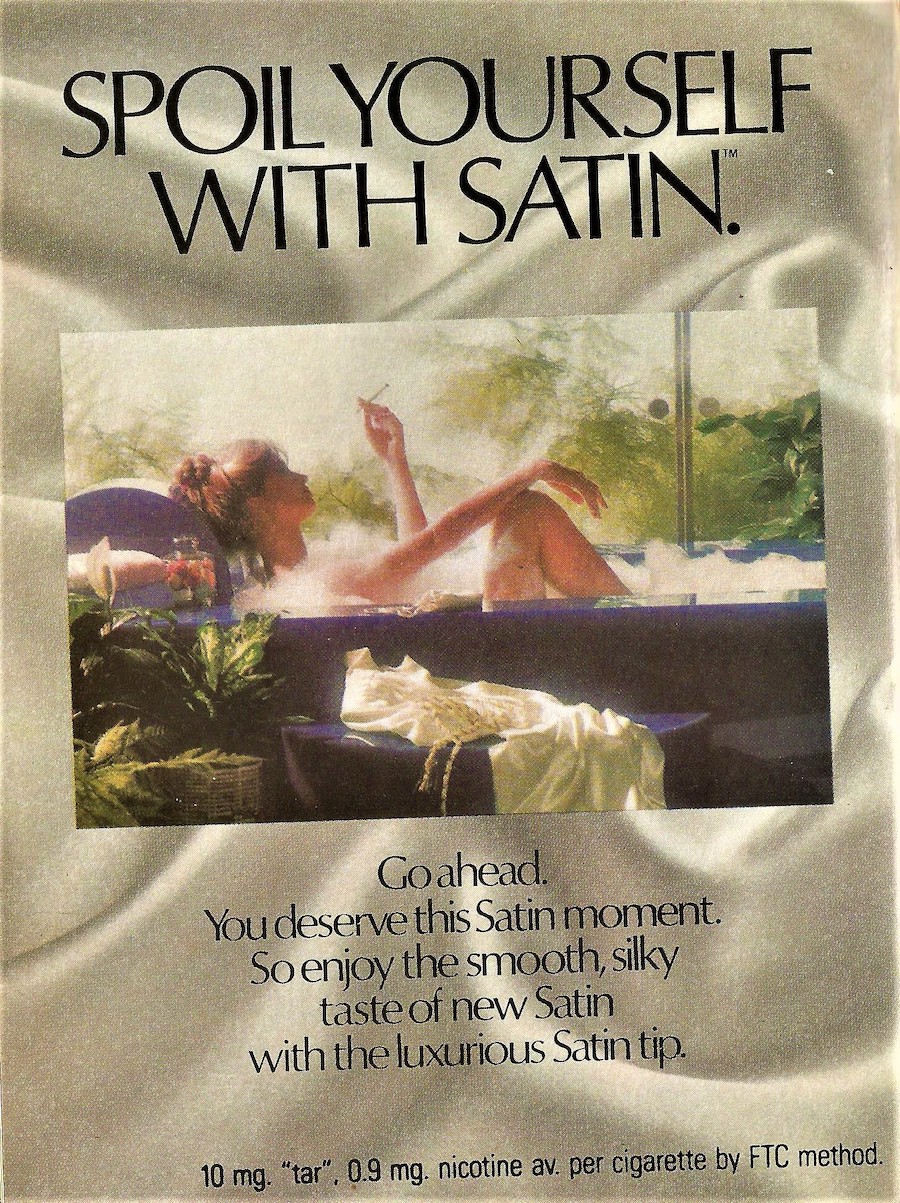

Starting in the 1950s, the release of five big studies on smoking’s detrimental effects started to change the game. Still, it wasn’t until the 1980s that the United States required warning labels on tobacco products, and until two years ago that France did the same. Perhaps that’s why the story of how Big Tobacco co-opted the “feminist cigarette” has gone under the radar.

The truth is, when we look at the cigarette’s place for women in what is estimated to become a $1.08 trillion industry in the next seven years alone, we are reminded of how quickly and effectively corporations can move to brand social movements. Remember those “We Should All Be Feminists” T-shirts that emerged during the #MeToo movement that didn’t actually help intersectional feminism? Same moves. Different package.

As a society, it’s easy to forget about the symbolism that can underly what we consume. We’re not advocating a return to the era of midcentury smoking, of course, but to revisit the histories of the little everyday objects that surround us. Chances are, they’ve got quite a story to tell.