Going into this, I don’t think I was prepared at all for how un-unique the story of Florida’s Sugar Hill neighbourhood really was. In the 1950s and 60s, the once upper class and prestigious Black community of Sugar Hill in Jacksonville, was chosen by city officials to be levelled to make way for a multi-lane expressway. Once known for its elegance and millionaire residents, Sugar Hill was left decimated, and what remains of it today sits largely boarded up, ghostly and overgrown. I found myself in a Google street view rabbit hole, despairing at all those neglected and condemned houses, comparing them to the vintage photographs of a once charming and prosperous neighbourhood. But when you begin looking into a story like this, you’ll quickly find others – almost too many to count – before you start to realise, with a great big lump in your throat, that these stories of lost Black affluence are found in every major city across America, where this exact same thing happened at the exact same time.

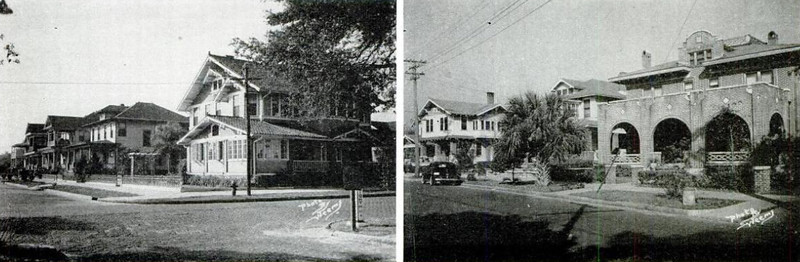

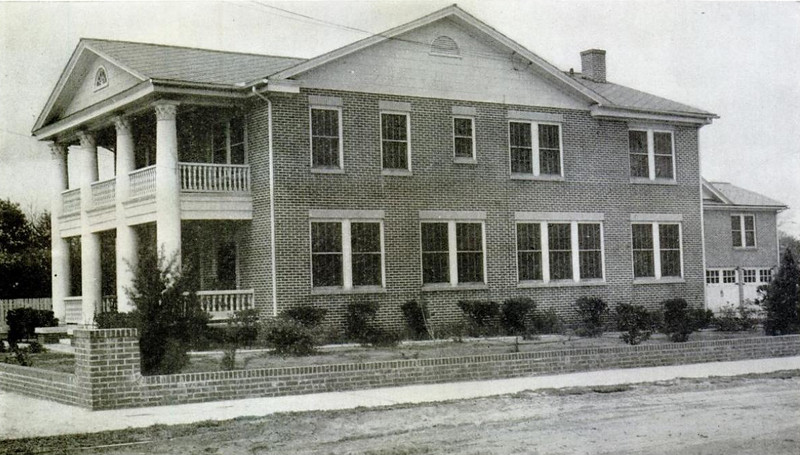

Local blog MetroJacksonville described the neighbourhood of Sugar Hill as a “prestigious upscale streetcar suburb” where Jacksonville’s most prominent African-Americans lived from the late 1800s until the 1960s. “Elaborate residences lined the streets … built on the back of Black prosperity in an era of heightened local racial discrimination”. But the construction of the Jacksonville Expressway in 1960 saw Sugar Hill’s mansions demolished, along with the neighbourhood’s prized 30-acre park which also housed the public library. Upon completion of the Jacksonville Expressway, Sugar Hill’s business district was decimated in one clean swoop. The once impressive tree-lined streets are now “lined with parking lots, McDonald’s and Walgreen’s Pharmacy”.

Typically, this kind of destructive urban development is presented to us as a textbook example of the “failures of modernism”. The more uncomfortable truth? For much of the 20th century, city officials and planning department officials had unrestricted powers to enact such development – and if White officials happened to be of the opinion that minority wealth and self-sustaining Black business posed a threat to affluent White communities, they certainly had the power to express it. Too often, it was the nicest minority neighbourhoods that were thriving the most, which somehow found themselves in the “path of progress”. The destruction of communities like Sugar Hill has been blamed on modernism’s failures, but highways have destroyed countless predominantly Black communities across America and we would be remiss to think it was simply “bad luck” and that systematic racism didn’t play a very significant role in that.

The same disregard and systematic disenfranchisement has happened in so many other ways too – they just aren’t always as visually apparent as a six-lane concrete expressway. “If you see dirt being turned on Sugar Hill’s vacant lots, it’s probably not new construction,” notes MetroJacksonville. “Instead, it’s more than likely the EPA replacing contaminated soil from a City of Jacksonville municipal solid waste incinerator that sprinkled ash all over the neighborhood from 1901 until the 1960s”.

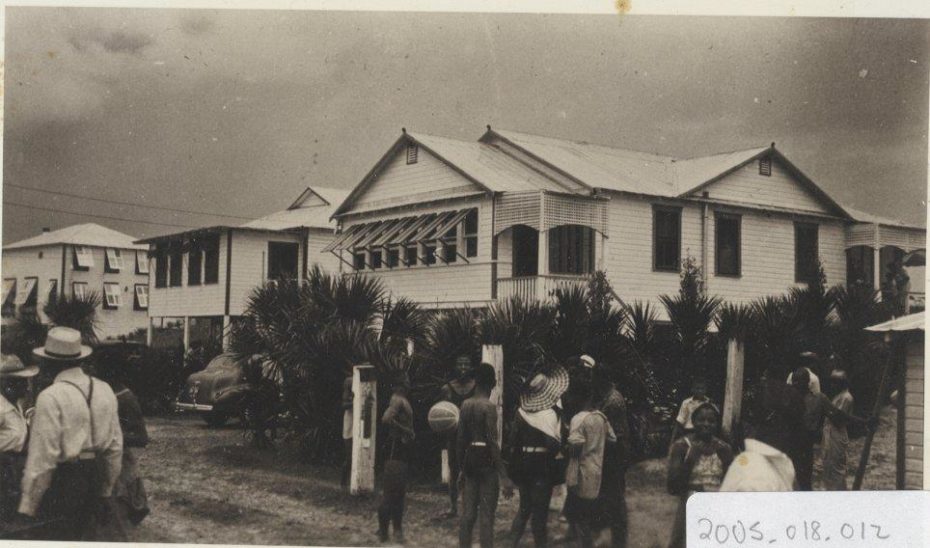

Desegregation too, ironically played a major role in the loss of affluent Black communities. Take the historic beach community known as “American Beach”, located just north of Jacksonville, founded by one of Sugar Hill’s wealthiest residents, and Florida’s first black millionaire, Abraham Lincoln Lewis. Popular with African-American vacationers during the time of segregation and the Jim Crow era, when African Americans were not allowed to swim at White-owned beaches, Lewis set out to create a refuge for his Black employees to vacation and own homes by the water.

Ray Charles, Cab Calloway and James Brown were among the celebrities that summered there in the 30s, 40s, and 50s, performing at the hotels, restaurants, and nightclubs. But the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 that desegregated the beaches of Florida, would mark the beginning of the end for a place like American Beach.

For all its positives, when desegregation came into affect, while minority populations suddenly had access to White businesses, this wasn’t exactly reciprocated. While people will take their steps upward, those already living in privilege are far less likely to do business, buy homes or travel in those communities.

The former African American resort known as “American Beach” became less and less frequented until it was just a ghostly stretch of sand lined by abandoned houses and neglected beach pavilions left to the elements. Abraham Lincoln Lewis’s own historic home, the first on the beach, was demolished earlier this year. His late great-granddaughter, MaVynee Betsch, also known to locals as the “Beach Lady”, began raising awareness for the declining beach area in 1977. Her efforts were rewarded when the National Register of Historic Places added the site, but the resort has never regained its former glory.

One could probably dedicate a school’s entire curriculum in history class to these kinds of stories, starting with better-known examples, like Tulsa, OK, Durham, NC and Richmond, VA; three American cities that blossomed into what became known nationally as Black Wall Street before the Civil Rights Movement. And there was that time New York City demolished Seneca Village in the 19th century to build Central Park, displacing a settlement of African American landowners in central Manhattan. There was Boyle Heights in Los Angeles too, Paradise Valley in Detroit, and “Bronzeville”, in Chicago.

Miami’s Overtown, the second-oldest continuously inhabited neighbourhood after Coconut Grove, once had a thriving art, music and entertainment scene comparable to Miami Beach, where the likes of Ella Fitzgerald, Josephine Baker, Nat King Cole and Billie Holiday stayed when they weren’t allowed to sleep at the glitzy White-only hotels in Miami where they’d been invited to perform. With urban renewal in the 1960s and the construction of several interstate highways cutting right through it, the once-thriving area was left fragmented, its economy decimated and the population slashed by nearly 80 percent. Only affluent or well-educated Blacks would’ve had the luxury to move elsewhere, leaving the poorest behind as local governments went about building freeways through historically Black neighbourhoods. Overtown has since been labelled a “ghetto”, ravaged by heroin addiction and gun crime.

While some places are more difficult to imagine than others as ever having seen a period of notable prosperity, historical archives can offer some clarity. The Carnegie Museum of Art has a collection of about 70,000 images taken by a press photographer who lived in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, a group of historically African American neighbourhoods, and documented the community between 1935 and 1975. Hill District was a significant cultural centre and home to many prominent jazz musicians until the city built a civic arena. It’s amazing to see what it used to look like compared to the giant park lot it is today. Ever wonder why sports stadiums and highways seem to be located in the “sketchier” parts of town?

Sweet Auburn, Atlanta, where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was born, and the Linden Community in Ohio, were normal middle class Black neighbourhoods that had freeways dropped on them by government programs and still haven’t recovered decades later.

The list of places, as you might have gathered by now, is long. Almost every city in America has a story where a freeway went through a minority neighbourhood and destroyed it. This is what is implied by systemic and institutional racism. And when someone asks “why haven’t Black people lifted themselves out of poverty?”, the answer is, they pretty much did – until it was destroyed, and the evidence got buried under some concrete highway.

If government programs had forced highways through affluent White neighbourhoods across the country – surely we would have learned about the aftermath in history class. The disenfranchising of Black communities and People of Colour in America is a story that goes as far back as the 1700s, and yet, we focus on reciting what wars and national incidents took place in what years. Perhaps if schools started by focusing on local history first, students could see first-hand the results of it all around them, making the connection and better understanding how relevant it is to the present.

Further recommended reading: The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs.