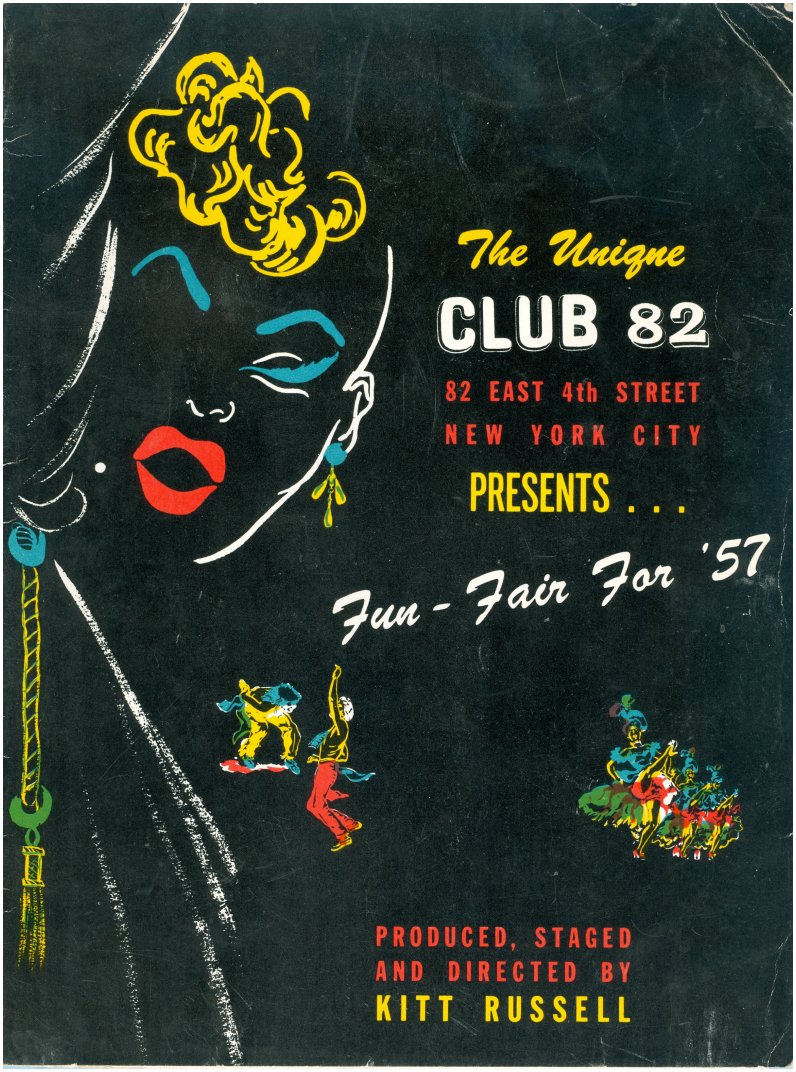

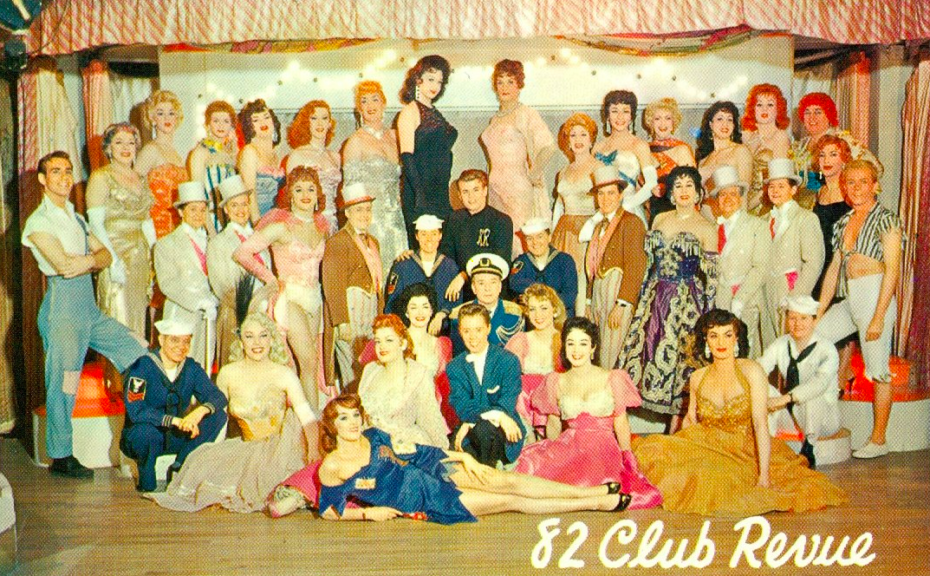

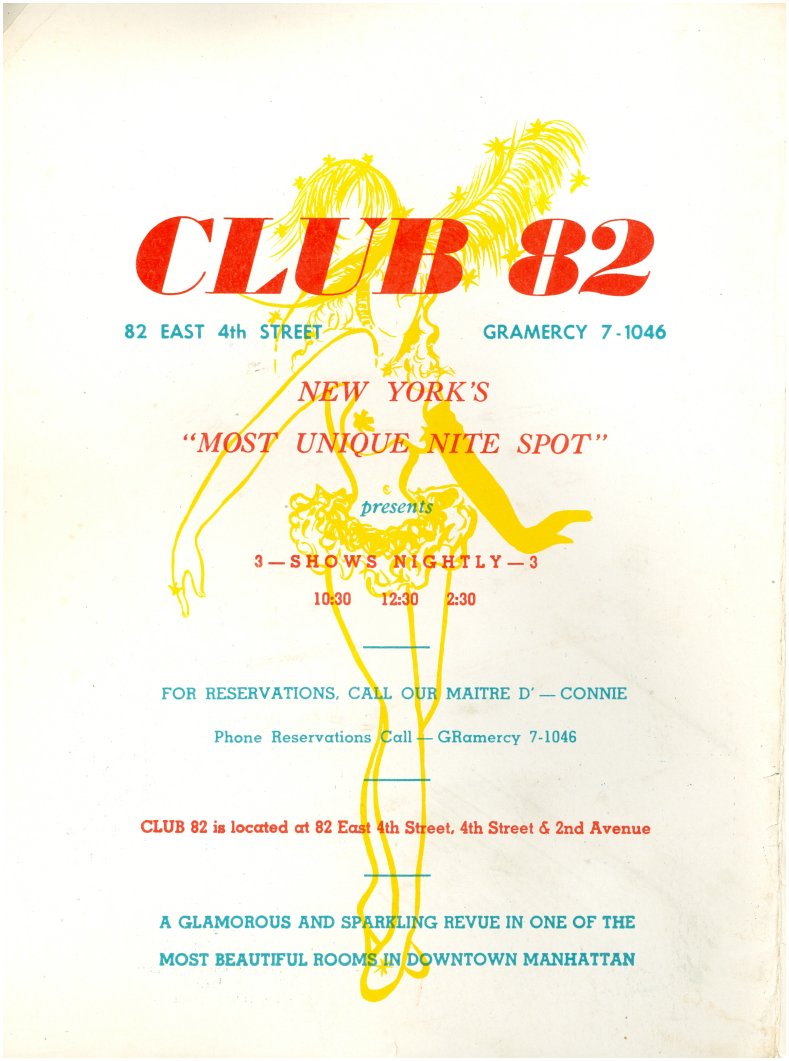

Bedazzled drag queens, mobsters, and Errol Flynn playing a piano with his errr … manhood? It was just another Saturday night at NYC’s “82 Club,” c. 1955. Tucked inside a nondescript door at 82 East 4th Street in Manhattan, “82” declared itself the “gayest rendez-vous”on the town in every sense of the word, falling somewhere between the Copacabana and RuPaul’s Drag Race. At once underground and well-known amongst a certain elite clientele, it was a hot spot for stars like Judy Garland, Frank Sinatra, and Elizabeth Taylor to observe a glittering drag revue that was way ahead of its time. So how did these queens pull it off in the era of Doris Day?

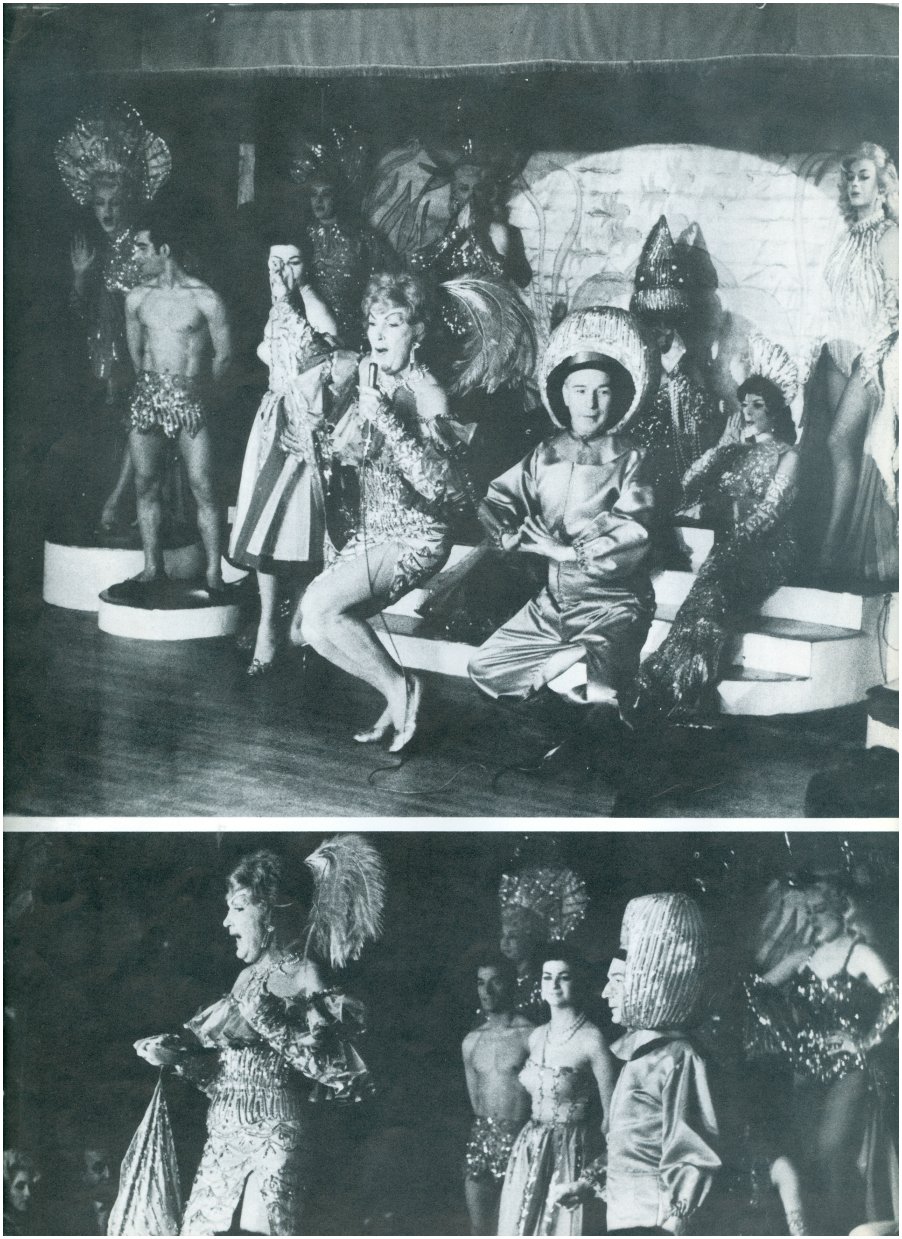

“Once you made it there, you’d descend the steep stairs into an elegant, transporting nightclub decked out in the height of mid-century kitsch,” writes the New York City Historical Society, “mirrored columns, plastic palm fronds, elaborate banquettes, and white tablecloths” abounded. It wasn’t uncommon to run into Salvador Dalí mingling with drag queens and local politicians. Ah, to have been a fly on the wall (or on the lip of a martini glass)…

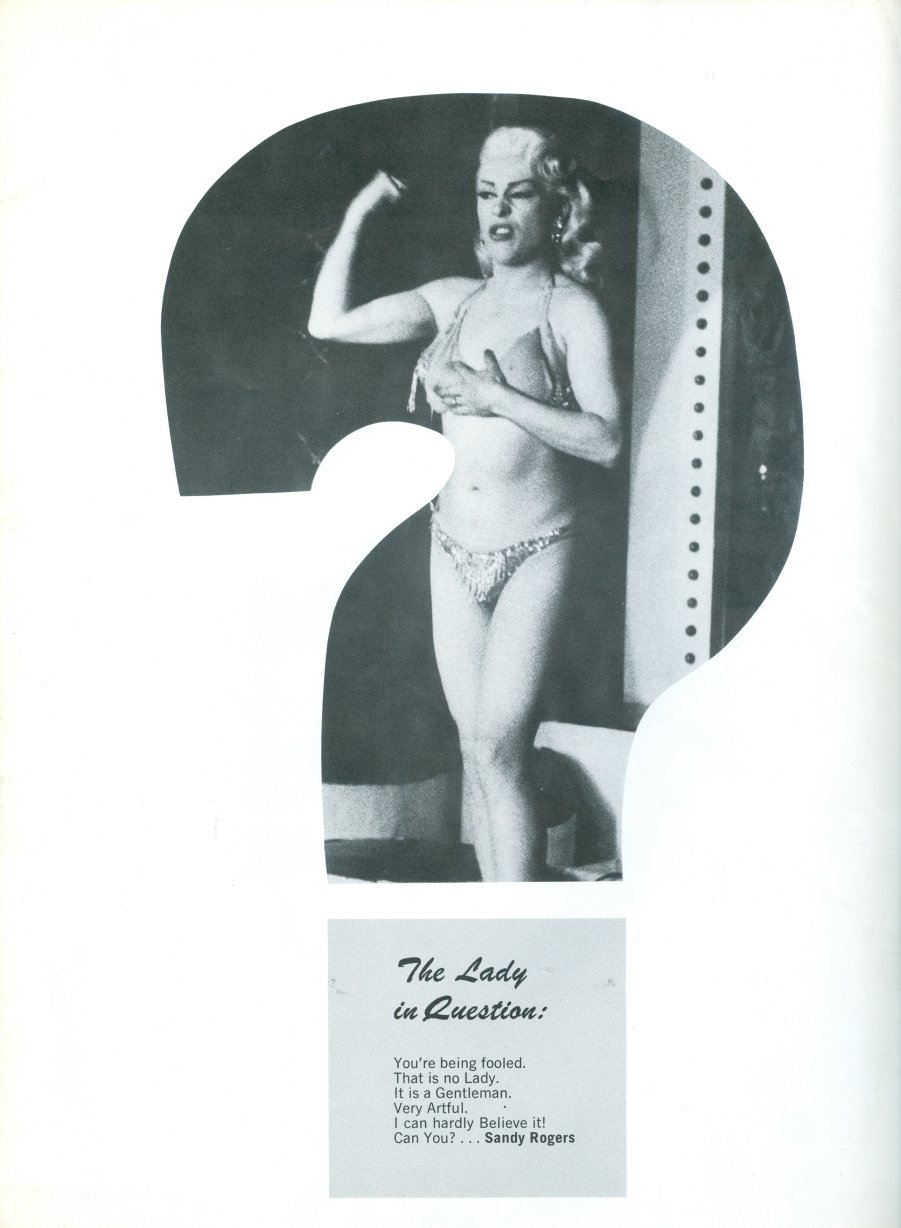

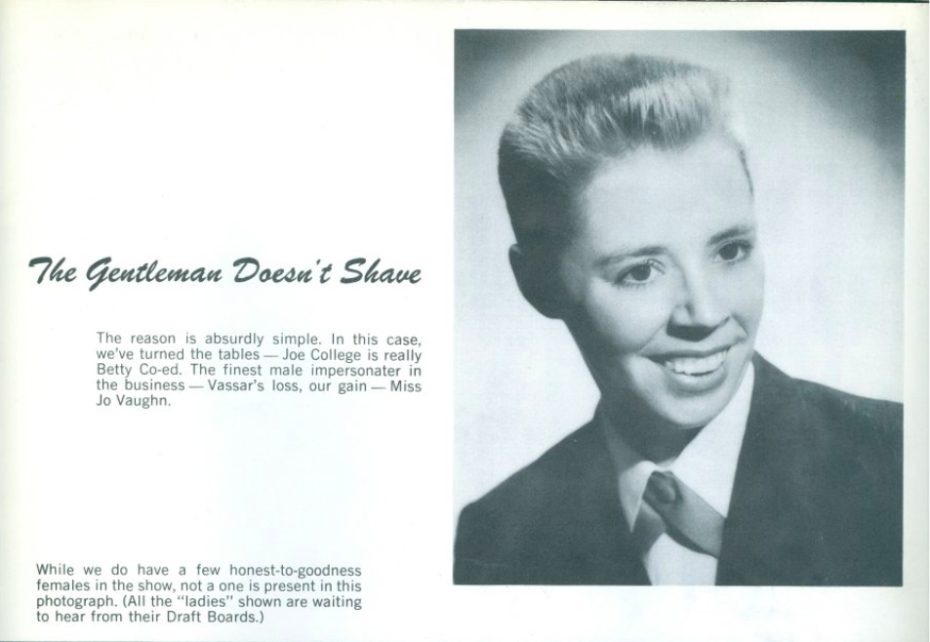

When 82 opened its doors in 1953, declaring yourself a drag queen – let alone a gay, gender queer, or non-binary – was a dangerous move in NYC nightlife and cabaret culture. These were the years of Leave It To Beaver, and the myth of the Nuclear Family. When queens performed, it was under a more euphemistic, hetero-accessible label like “female mimic” or “gender impersonator.”

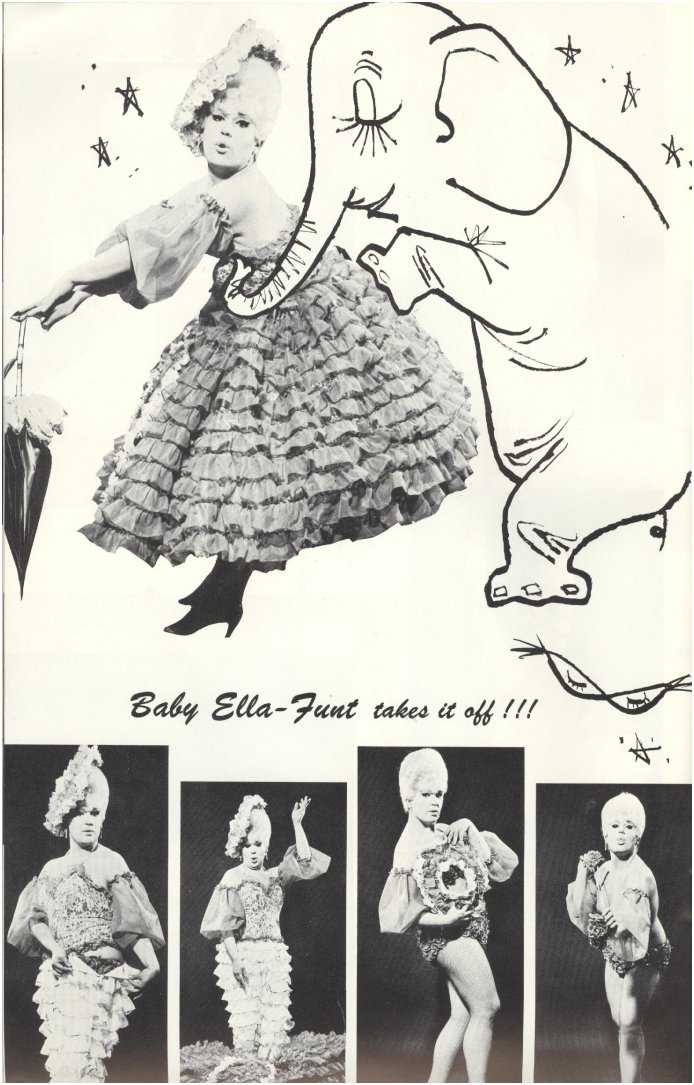

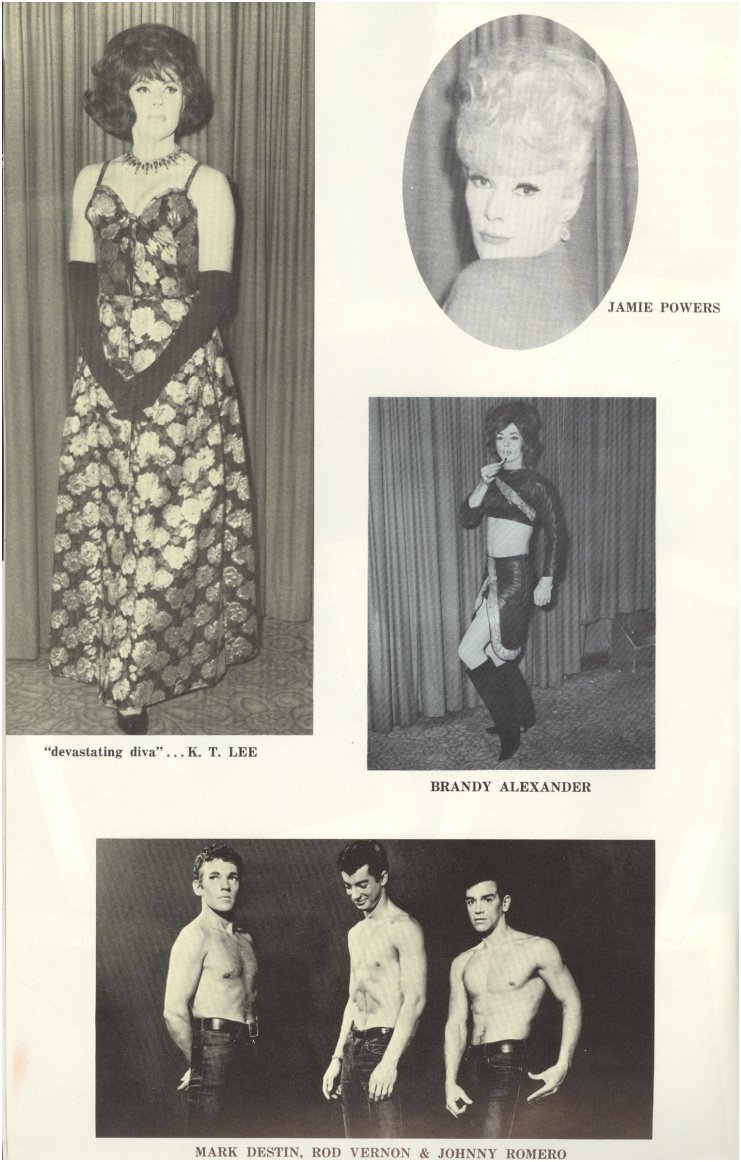

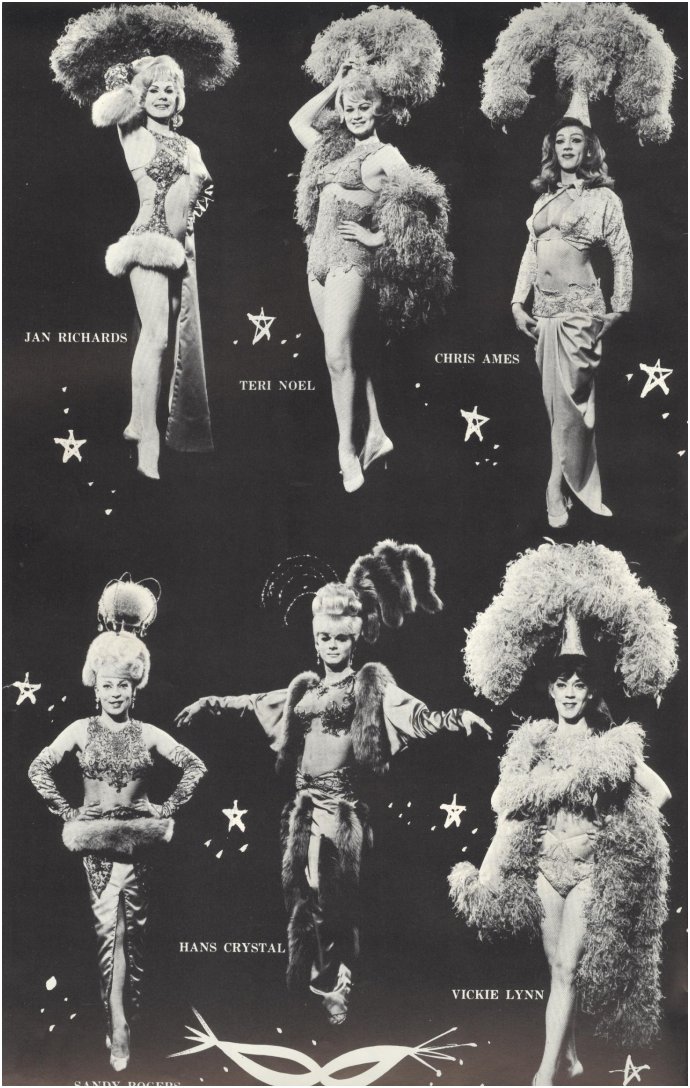

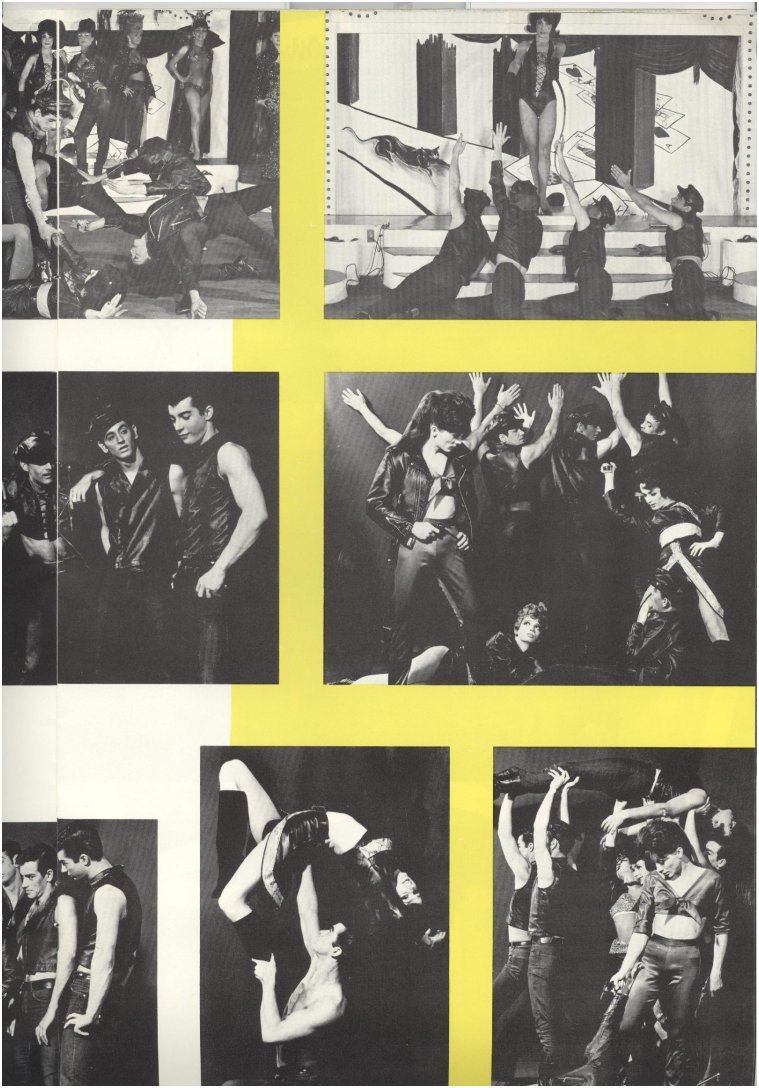

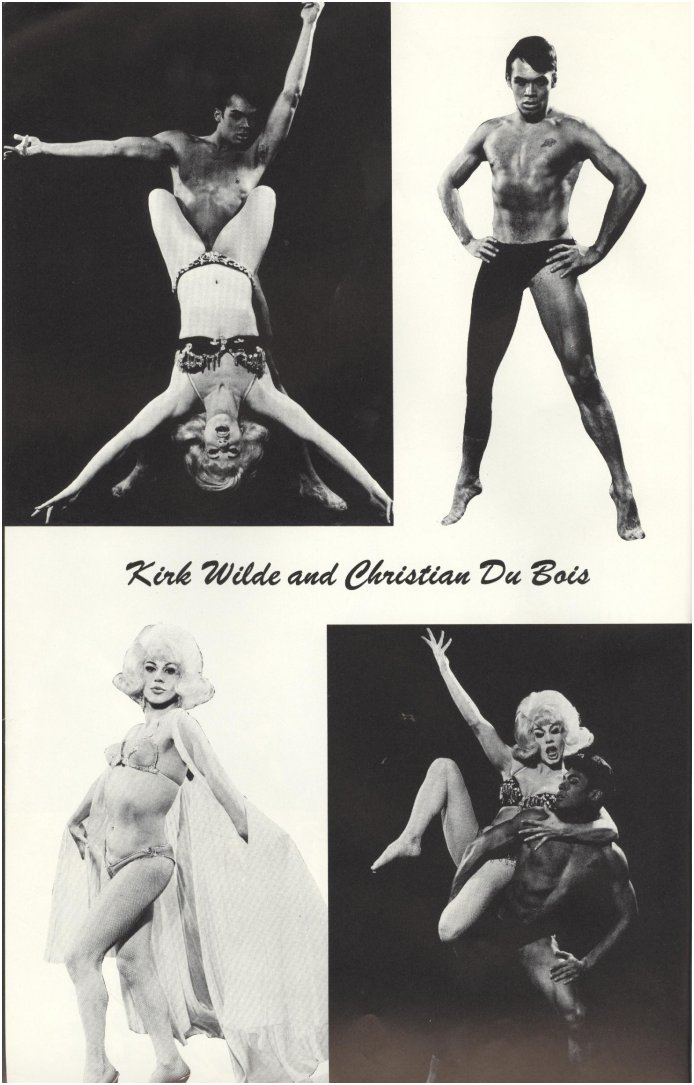

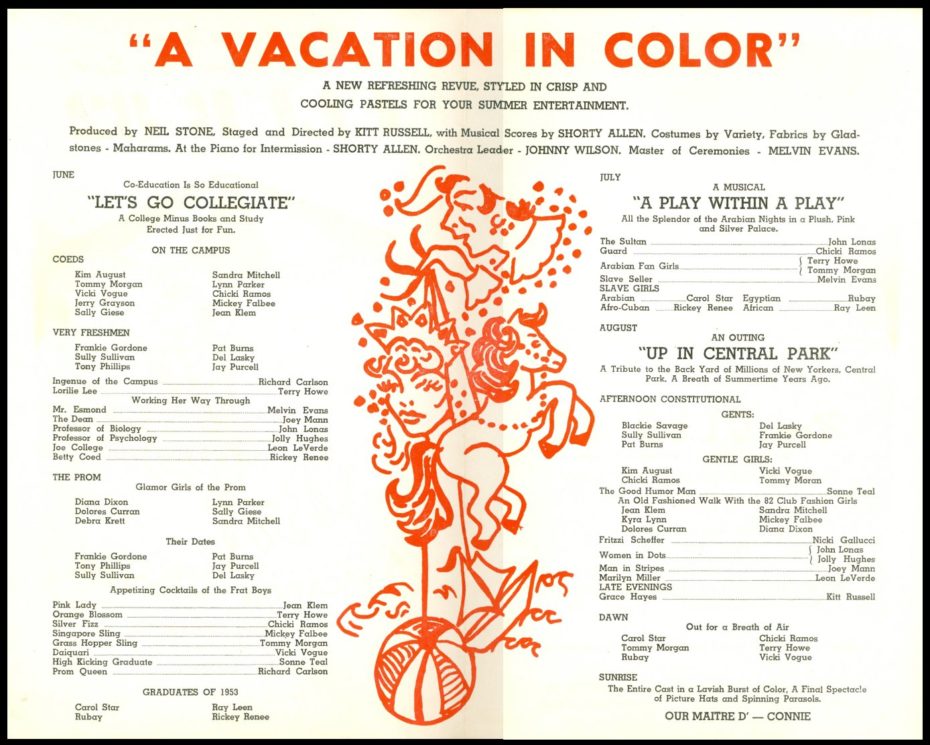

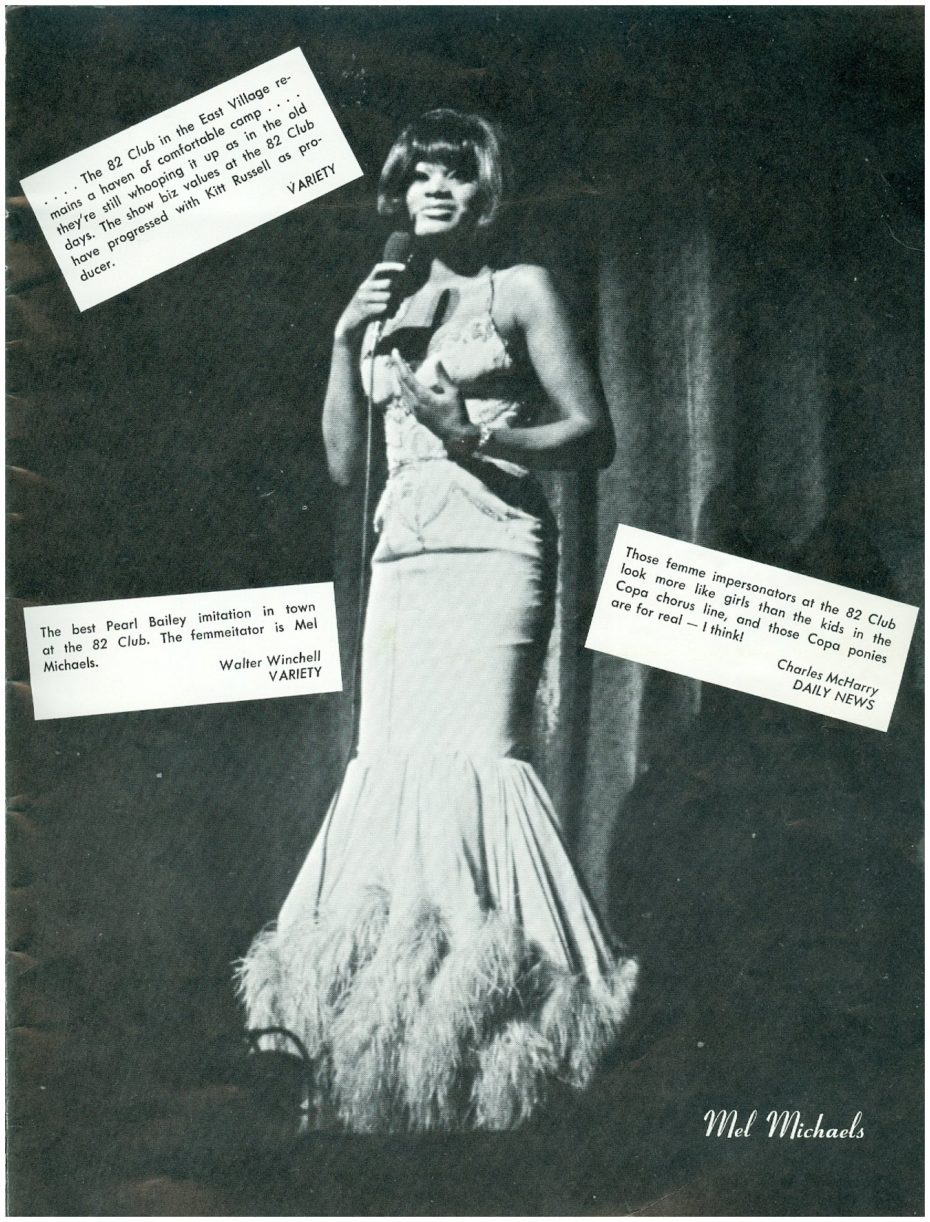

Highly choreographed performances ran like clockwork three times a night – 11:30pm, 12:30am, and 2:30am – to the sweeping tunes of orchestra leader Johnny Wilson. The ladies were decked out in glamorous costumes by designer John Wong.

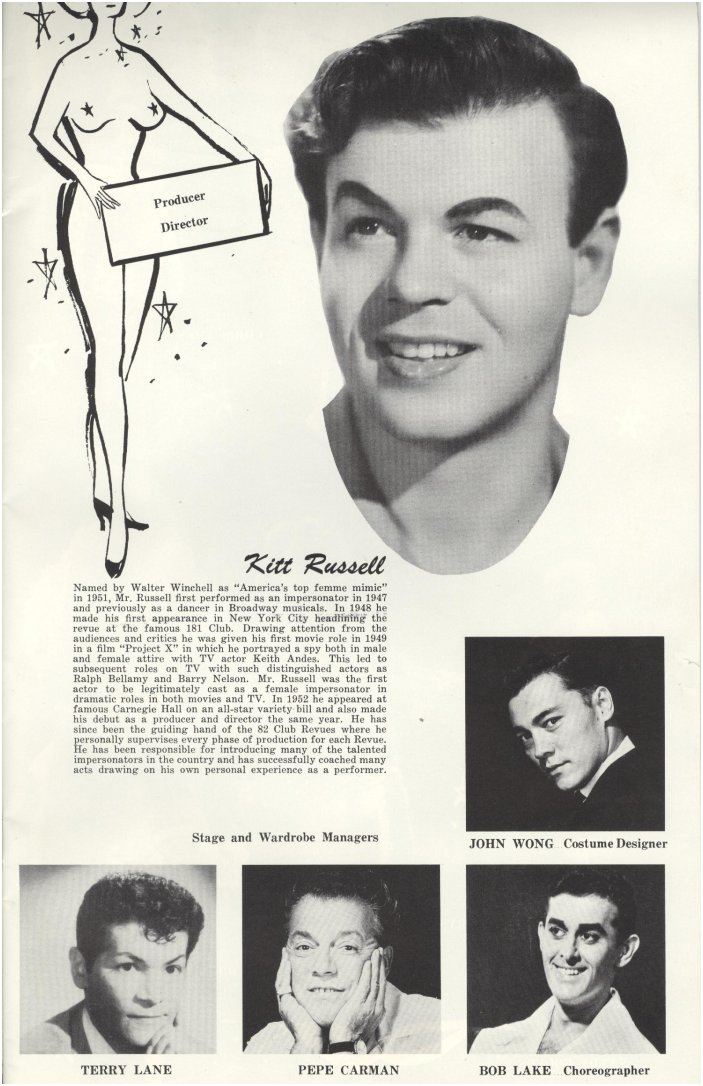

The shows were directed and produced by Kitt Russel, who came from a lot of Broadway experience and was a killer actor himself.

Here he is out of drag:

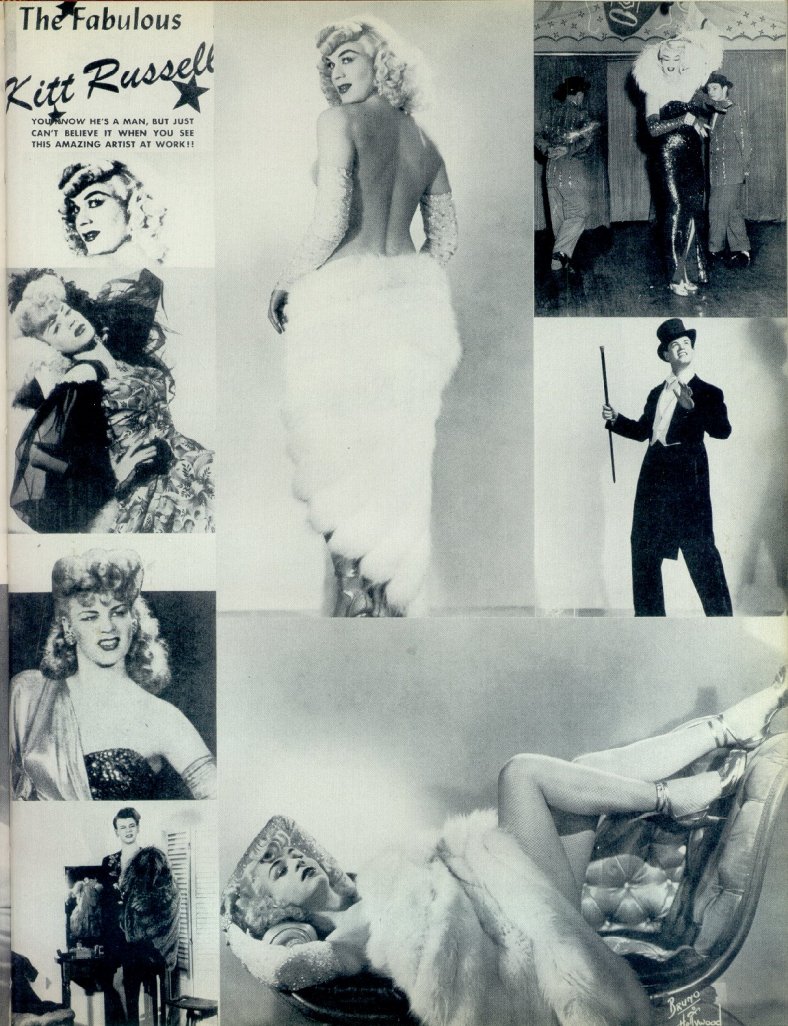

And in drag, serving us a blend of Mae West and Rita Hayworth energy…

We get the spins just looking at the fantastic programmes past, which offered a non-stop parade of charisma, high kicks, and plenty of double-entrendres. Take the “Vacation in Color” revue from 1956, with its cheeky take on Americans’ famously undying devotion to ra-ra school spirit. “Let’s go collegiate,” read the programme, “[with] a college minus books and study erected just for fun”…

They payed homage to the Ziegfeld Follies and travelling circuses; they danced the Charleston, spun around in leather chaps, and sang songs harkening back to the Roaring ’20s. In the span of about a decade, the club churned out dozens upon dozens of well seasoned drag performers…

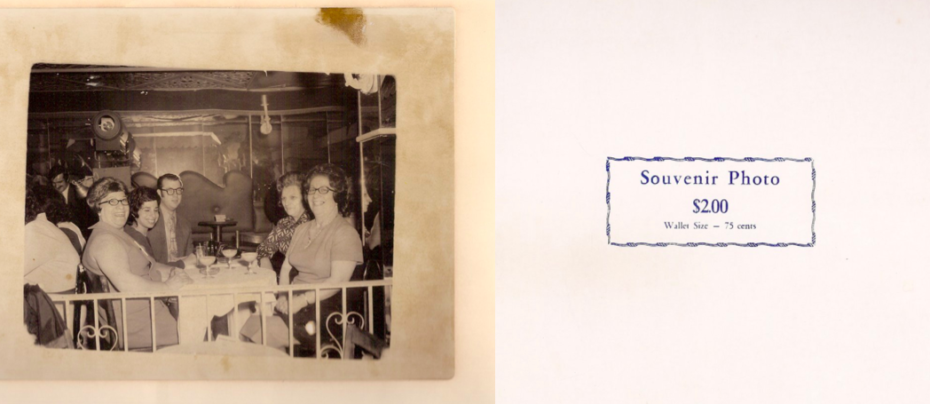

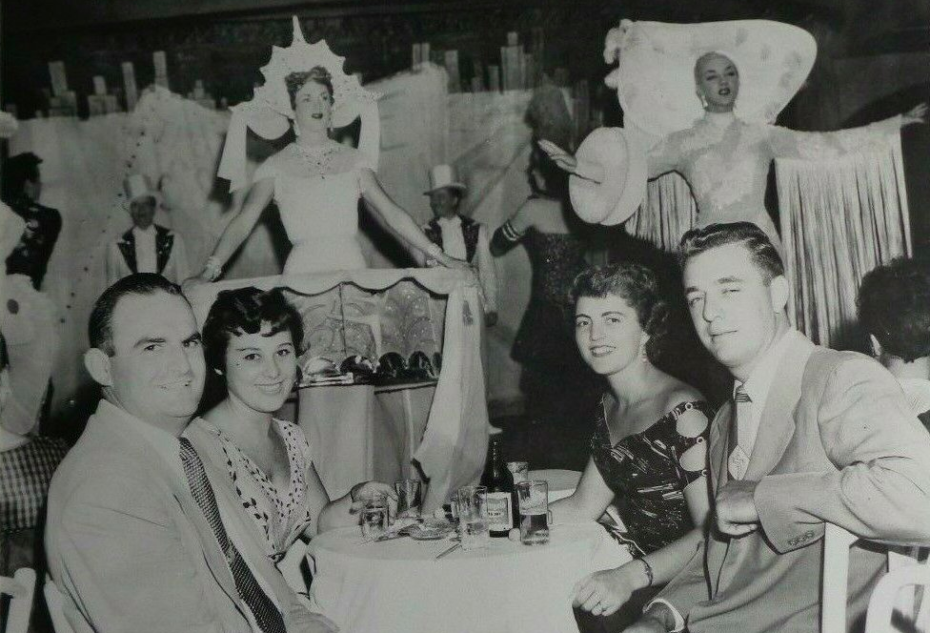

The branding at 82 was also top-notch, with keepsake postcards and photos available for today’s equivalent of about $10, and little wooden “drumsticks” given out to guests; the idea was that you could tap on your tabletop in lieu of clapping. That way, your drink never left your hand.

It’s a bit of a head trip to see the souvenir photos, which look like they could’ve been snapped in a wholesome Midwestern supper club, instead of a risqué New York City drag show – remember, cross dressing was still technically illegal.

That’s the thing about Club 82’s legacy. It’s success hinged on catering to the city dwelling, middle to upper-class straight white elite. Most of the performers were white, the clientele was white, and while the staff and performers were largely gay, their audience was not.

Another crucial, if not thee most crucial part of 82’s success was due to the unlikely pairing of American-Italian mobsters and the East Village’s ostrich feathered queens, which ran strong from the 1930s to the late 1960s. “The law made the gay bars illegal,” reads one gay barman’s account in The Mob and the City by C. Alexander Hortis, “The Family made it operable.”

Just as they did with Prohibition, local mobsters like Vito Genovese carved out a physical space to both capitalise and encourage queer culture to thrive, albeit inadvertently; the mob founded the lesbian “Howdy Club,” and even the now-iconic Stonewall Inn. All the latter had to do was slip $1,200 into the NYPD’s back pocket every month.

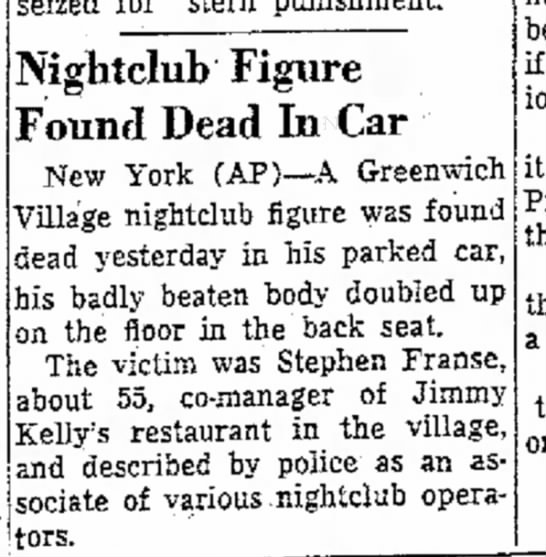

It was mafia man Stephen Franse who started the 82 Club, which had once been a speakeasy called the “Rainbow Inn” in the 1930s. He was a veteran of the gay bar scene – though apparently not gay himself – and also started the “181 Club,” affectionately known as “the homosexual Copacabana,” above a Yiddish Arts Theatre until he lost his liquor license. The real puppet master of 82, however, was Vito Genovese. Apparently Genovese’s wife Anna helped him run gay clubs around town and was 82’s hostess, and known to “like the girls” herself.

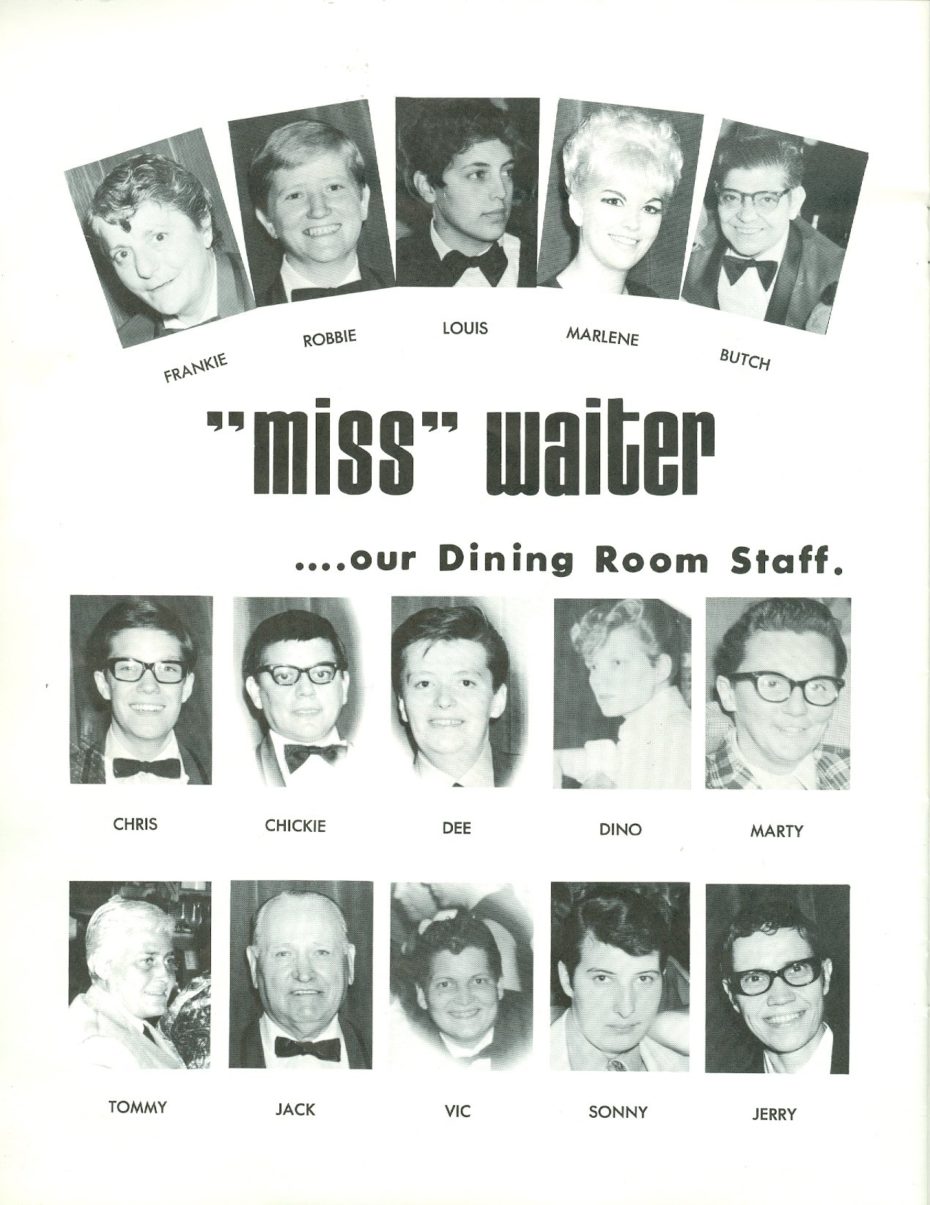

What must it have been like, to be not only be a lesbian woman on that scene but a lesbian mobster’s wife? Club 82 was centred around catering to men, and serving up men in drag, but it did hire women in male drag – often, lesbians – to serve as waiters.

Still, there was a toxicity to this interdependency between the mafia and the LGBTQ+ community. You didn’t have a mob wife like Anna running every gay bar. Even Club 82’s inception proved violent, when Franse was immediately offed by Vito in light of a row between himself and Anna, whose marriage was crumbling.

Raids and police violence still occurred despite pay-offs, evidenced most notably by the Stonewall Riots of ’69. At the end of the day, the mafia prioritised prophet over equality, and by the late 1960s the queer community took even more hold of its autonomy through gay rights organisations like the Mattachine Society, whose NYC branch challenged the State Liquor Authority’s discriminatory ban in 1966 with the iconic “Sip-In” at another NYC gay bar, “Julius.”

The dawn of the 1970s saw gay New Yorkers more fed up than ever; fed up with hiding, and fed up with catering queer culture to a non-queer audience. The crew at 82 was no exception, and in the wake of the mob fallout the club transitioned into place for glam rockers. The New York Dolls performed there, and apparently Lou Reed and David Bowie were regulars. Its curtain call as a queer performance venue came in the 1980s, and became an underground sex theatre called “The Bijou” that shuttered in 2019.

In many ways, 82 Club’s story is still unfolding, still growing as the mainstream culture finally moves to amplify and preserve those histories. In 2018, The New York Times ran a piece on “the hidden places in Manhattan where gay night life once flourished,” and highlighted Under the Mink, a book that explores the relationship between lesbian and gay groups and the mob in NYC.

82 Club is one of its biggest focuses, and author Lisa Davis prefers to immortalise it on a positive note. “Straight people came because gay people were so much fun,” she says, “One day I was walking by with my partner and I was telling him this used to be Club 82. I pushed on the door and it just opened and the smell was like 1974.”

What will become of the space post-covid is anyone’s guess. But boy would we love to see such a landmark of LGBT+ history come alive again.