When you think of Indian cities like Mumbai, Delhi and Jaipur, you might think of the impossibly intricate architecture, ancient folklore, explosions of colour and unstoppable energy; a welcome deluge of the senses. But there is one place that is not like the others. In the north of India, on the foothills of the Himalayan mountains, a modernist’s raw concrete city from another time and place came to be, constructed entirely from one architect’s experimental master plan. Far from his European roots, it was here in India that Le Corbusier, the father of Brutalism, was finally given the blank canvas he yearned to plant his ultimate seed. In the 1950s, the young republic, newly independent after years under the thumb of the British Empire sought to show the world that a new India had arrived, one that could prosper on its own. And so, on this vast area of flat, arid and mostly empty farmland, the world’s most unlikely urban planning projects came to be…

In 1947, in a time of uncertainty and displacements, India was being divided into different states. The first prime minister of the country, Jawaharlal Nehru, set out to create a new utopian city that could symbolise their new sovereignty and a prosperous future of urban growth.

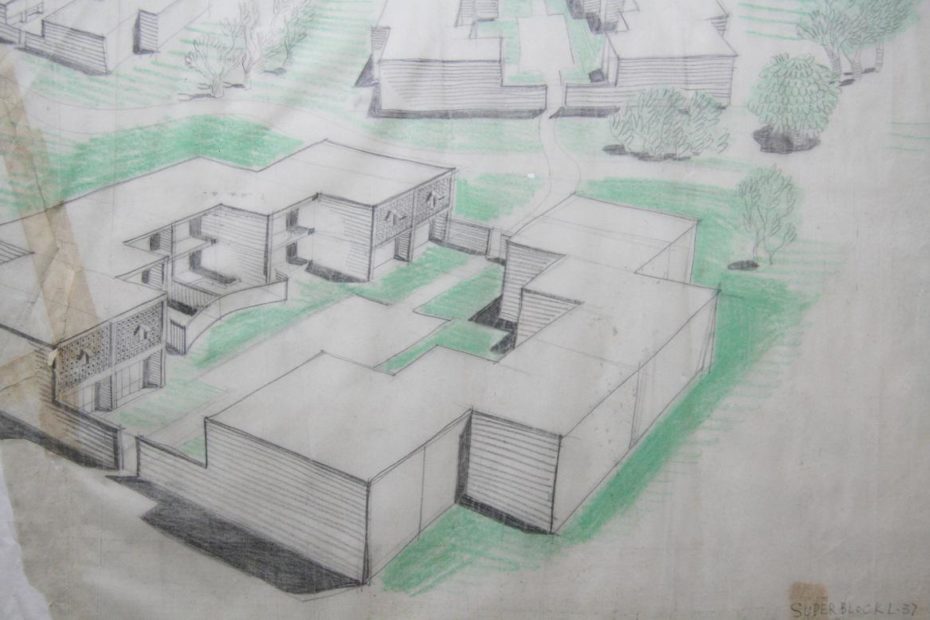

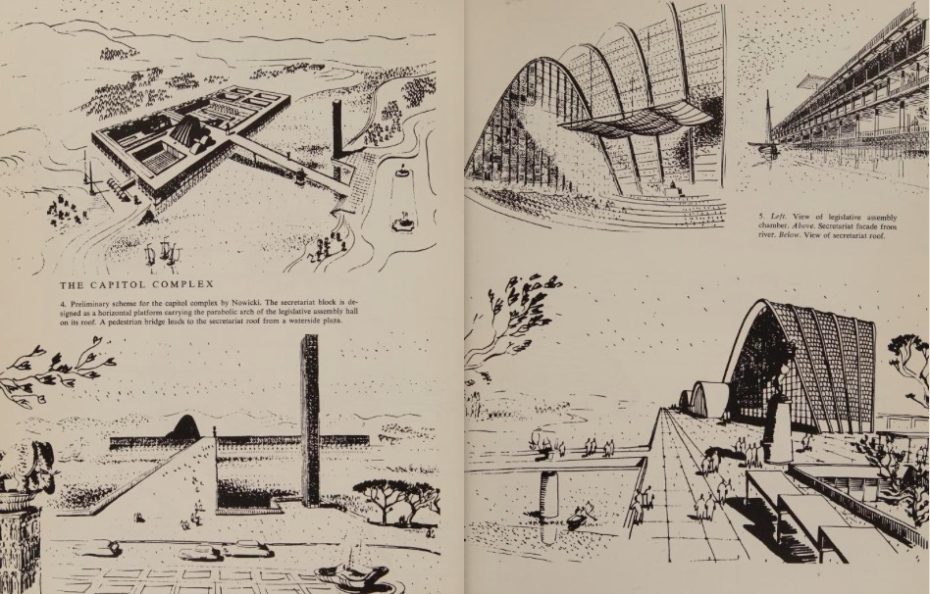

He would call it, Chandigarh, referring to the Hindu goddess Chandi and Garh, meaning fortress. With a lack of urban planners trained locally however, Nehru went looking across continents to find one. Initially, the project was put in the hands of an American architect and planner, Albert Mayer, who was responsible for numerous apartment buildings in New York and who had worked as an engineer in India with the US military during the Second World War. Together with his partner, Maciej Nowicki, a Polish architect who had helped reconstruct post-war Warsaw, they conceived a plan reminiscent of idealistic American suburbs, inspired by the utopian garden city movement. When Nowicki tragically died in a plane crash in 1950, Mayer stepped down, and the Indian prime minister resumed the search for his utopian architect.

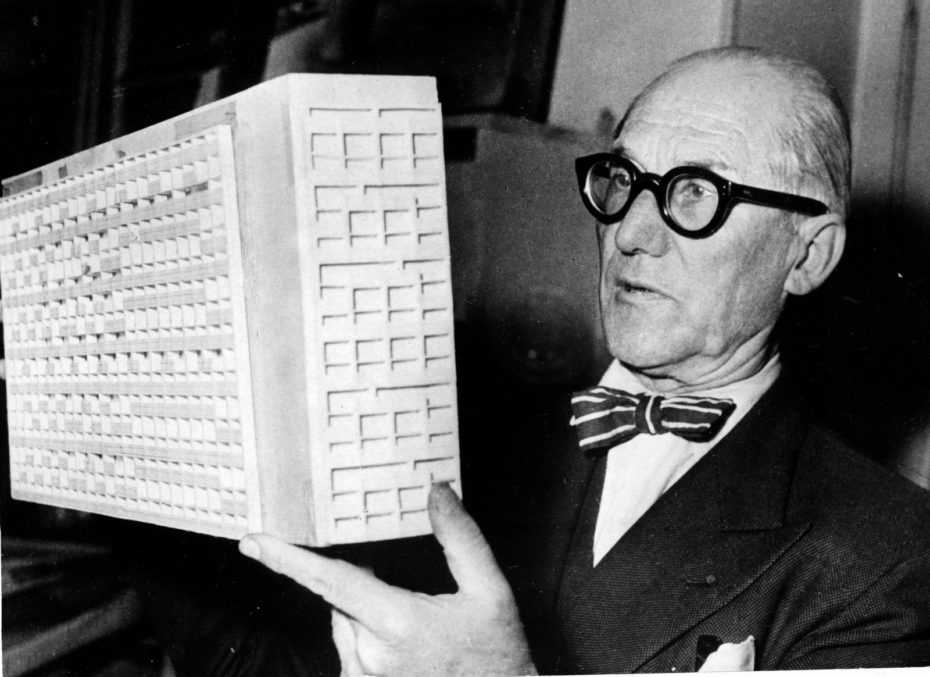

Enter Le Corbusier, perhaps the most renowned architect of the time, who envisioned a new world in the form of Modernism. At first he was sceptical to accept the undertaking of the project, dismissing the salary as beneath him. After much persuasion, Le Corbusier came around not for the money, but for the legacy. At the age of 70, he had never been given the chance to fully realise one of his urban planning projects from scratch before. In the 1920s, the French had vehemently rejected his proposal to raze a large portion of central Paris and rebuild a new concrete business district.

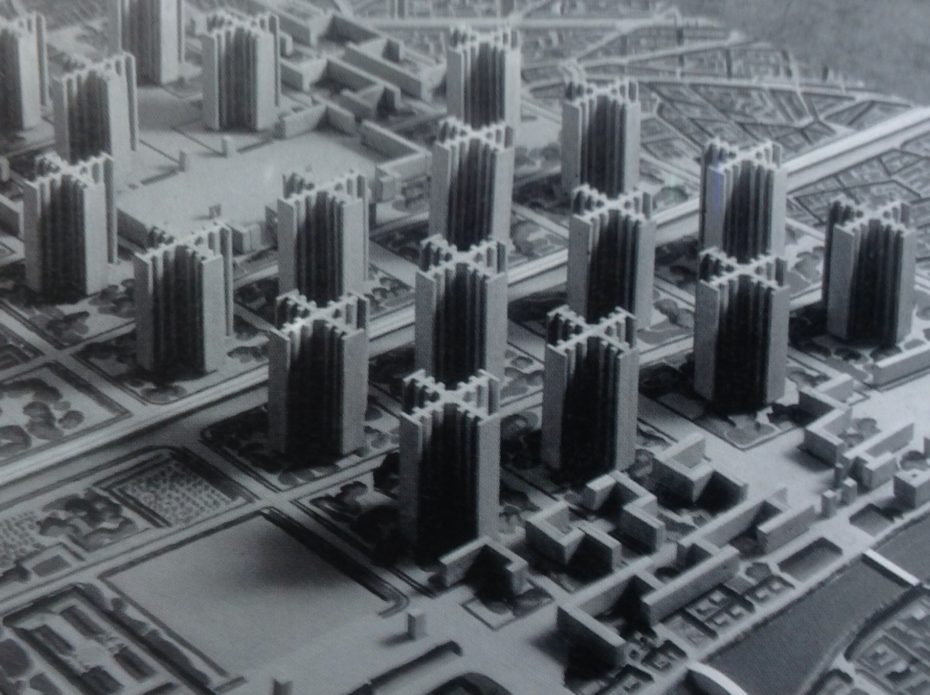

Motivated by the economic segregation of late 19th century Paris that saw the poor pushed out while the bourgeoisie remained in the city center, the utopian urban concept he called “Plan Voisin” intended to house three million inhabitants in a series of skyscrapers. Without the hindrance of his French critics, this was the architect’s final chance to create a zenith of his life’s philosophies.

Chandigarh was designed to have its own grand boulevards, plazas, and divided districts like Paris’s arrondissements, with their own housing complexes, amenities and schools. His initial idea consisted of a vertical city where the roads were elevated with green spaces below. It was ambitious not only in realisation, but also in budget. Instead, he updated Mayer and Nowicki’s plan, adapting it to a more geometric layout and of course, prioritising the use of beton brut, the raw concrete that gave the Brutalist movement its name.

It’s debated however, exactly just how hands-on Le Corbusier was with the project day to day. He refused to move to India for its construction and reportedly only visited the site a few times a year. He recruited his cousin Pierre Jeanneret, as well as English architects Jane Drew and Max Fry as senior designers. While Le Corbusier took over the wider task of planning, his colleagues focused mostly on designing many of the individual buildings themselves.

In her book about the urban planning of Chandigarh, Norma Evenson reveals, “Pierre Jeanneret wrote to his cousin [Le Corbusier] that he was in a continual battle with the construction workers, who could not resist the urge to smooth and finish the raw concrete, particularly when important visitors were coming to the site.”

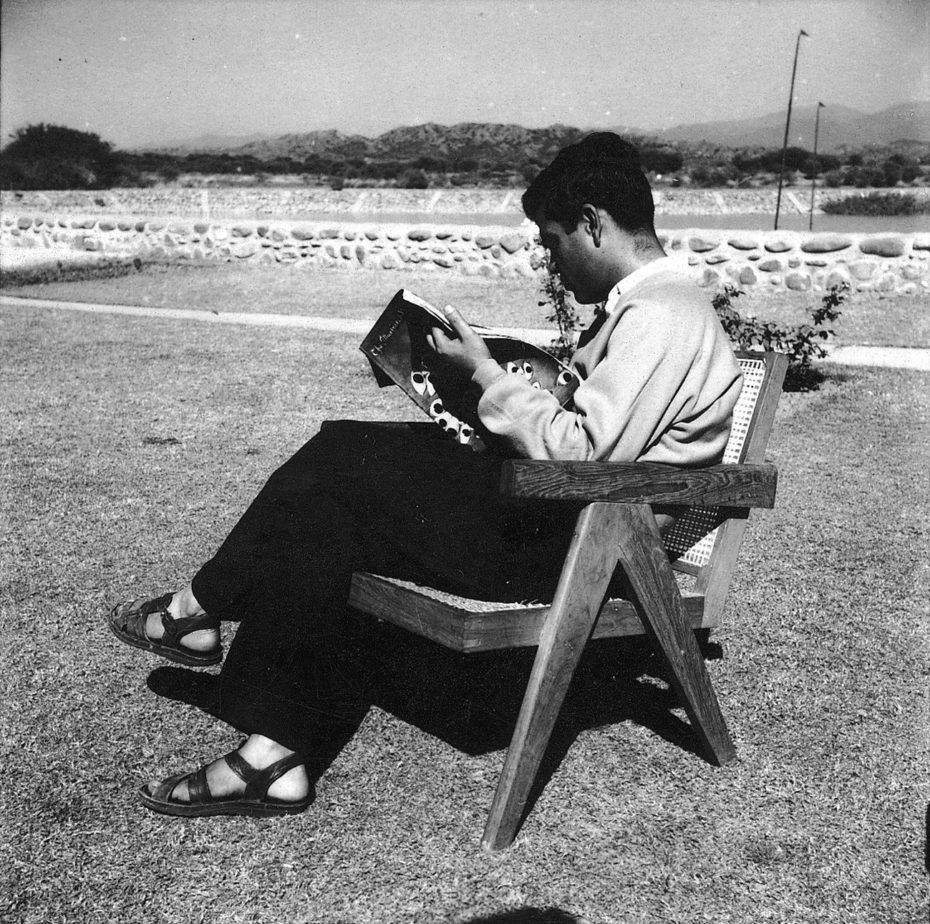

Le Corbusier’s cousin, Pierre Jeanneret, contributed to finer details like the light fixtures, furniture, all the way down to the doorknobs. If his name rings a bell, it’s probably through your appreciation of Modernist furniture that you’ve become familiar with the highly coveted piece of furniture he designed specially for the city of Chandigarh…

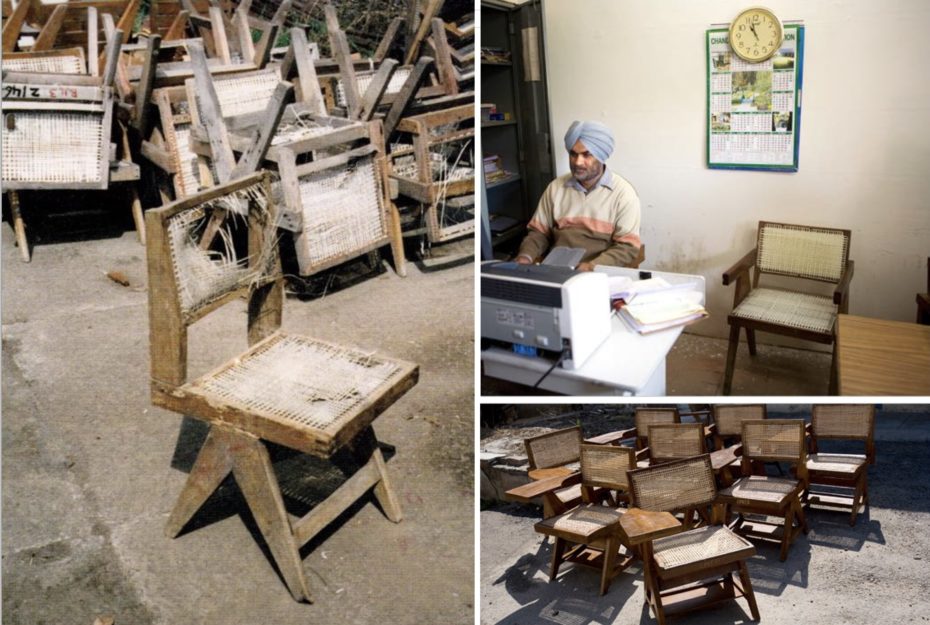

In a new city that was being built from scratch, there were no interior design shops to outfit Chandigarh’s public buildings, so Le Corbusier’s colleagues designed their own furnishings, most notably Jeanneret’s Modernist woven rattan chair. Today, it’s considered an iconic piece in the interiors world. Original and restored vintage pieces salvaged from the experimental city sell for eye-watering prices at auction, while interior trends are currently at their peak for various imitations of the wooden rattan Modernist look, first created for the people of Chandigarh.

The New York Times spoke to the local principal of the Chandigarh College of Architecture who had been stunned to learn of the prices that Chandigarh’s chairs were being sold off for at top western auction houses. “We found out that we were sitting on a pot of gold, quite literally,” he said, referring to the chairs which had come to be overlooked as standard office furniture.

At the turn of the century, dealers from London, Paris and New York began visiting the junkyards in Chandigarh, snapping up disused stocks of furniture for nothing, only to sell them off for upwards of $10,000.

When the city wised up to its error, an initiative was launched to begin restoring their vintage furniture locally, even commissioning inmates from the local jails, but “the dealers had realized much earlier that there was big money to be made.”

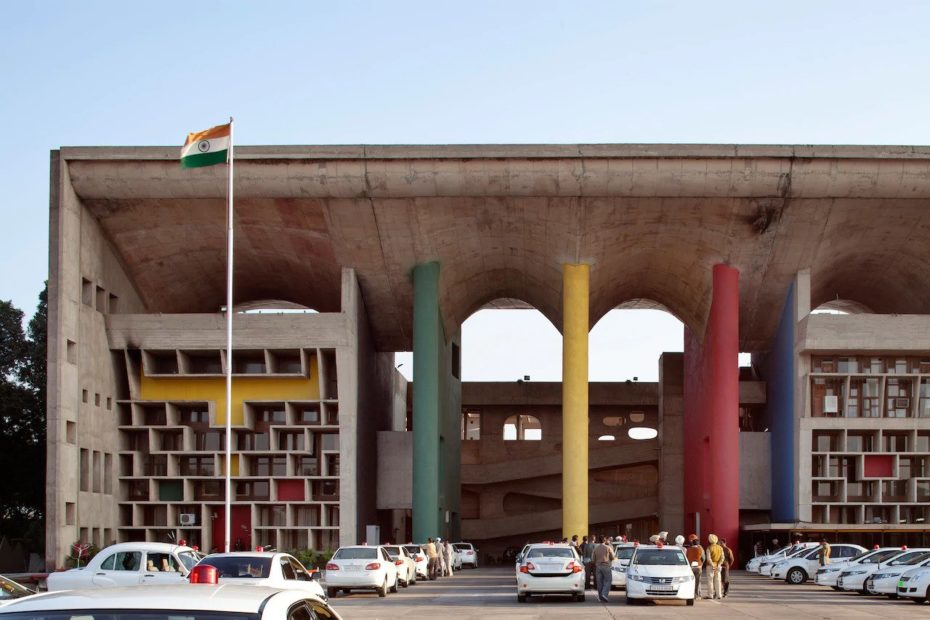

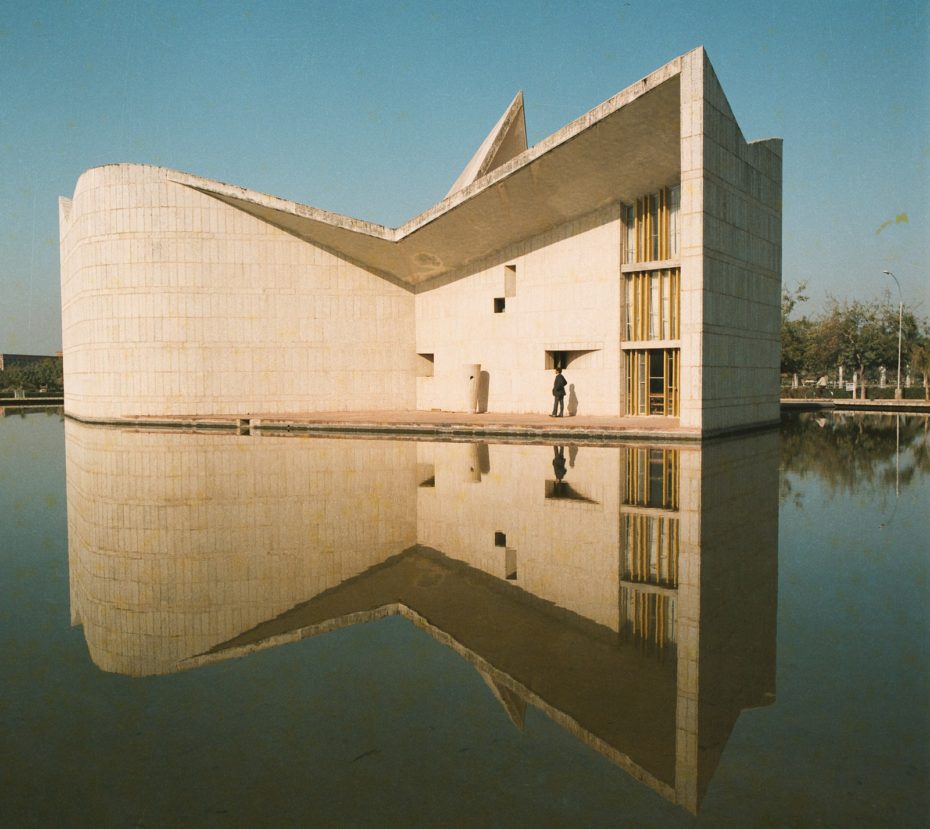

Arguably the unmoveable showpiece of Chandigarh, however, is the Capitol Complex, which is where the government headquarters and administrative offices are. Today, it’s a UNESCO World Heritage Site, made up of The Secretariat Building, The High Court of Justice and The Palace of Assembly. In alliance with Le Corbusier’s philosophy, who designed his projects by making an analogy with the human body, this area is like the “head” of Chandigarh.

There’s something arguably spiritual about the city too, with its open spaces, harmony, and monumental architecture. The open hand designed by Le Corbusier gives it a special sense of divinity, too. It’s like a sign of surrender, openness, reminiscent of Picasso’s peace dove. Indian officials didn’t want to erect it initially because of funding issues, but this was something that Le Corbusier really pushed for.

The concrete buildings might look cold at first, or even sinister like something out of The Hunger Games, however the closer you look, the more innocent they are. The splashes of bright colour are fresh and youthful, and the cut out shapes and visceral textures are unexpectedly playful.

Chandigarh would go on to inspire Oscar Neimayer’s infamous Brasilia plans and be revered by many as one of the world’s greatest architectural treasures, but Le Corbusier died in 1965 without having seen the final result of his Indian Odyssey.

Decades later, this alien utopian city in the foothills of the Himalayas has started to show some cracks. Many of Le Corbusier’s most emblematic concrete buildings have fared badly in the Indian summer heat and monsoon seasons. In 2005, city authorities launched restoration campaigns, but as new architects take the baton to guide Chandigarh’s development, many fear Le Corbusier’s vision (along with his “raw concrete” aesthetic) is being gradually eroded in the process. Other argue, the city’s future is encumbered by its growing preservationist “museum” status.

The city now also faces the challenge of overpopulation. Initially designed to accommodate 500,000 inhabitants, its expected to be home to 1.6 million inhabitants by 2031. Slums continue to expand outside the city, the very opposite to Le Corbusier’s dream. But against all odds, Chandigarh has become India’s wealthiest city per capita and the city seemingly continues to flourish as one of India’s wealthiest, cleanest and happiest cities.

The city is alive as Le Corbusier intended, but just how far in the the future did his utopian vision stretch? The next generation’s students of urban design may want to add this one to the travel bucket list to find some answers.

For more Messy Nessy travel tips in India, see our India tips in the Destination Directory or check out what’s in the vault below ↓