“Why are there so few Black American archeologists?” asked Maria Franklin in response to a landmark 1997 survey which found that only 2 out of 1500 Archeological respondents identified as Black. Years later, the status of her question posed in a paper published by the Cambridge University Press in 2015 – and its answer – is just as important. What do we talk about when we talk about “Black Archeology”? What does it mean to break away from the romantic colonial gaze on, say, Egyptology? We had a digital fireside chat with Ms. Franklin, archeologist and a professor of Anthropology at the University of Texas, for a little education.

“I started collecting old buttons, knick knacks,” says Franklin about her childhood and the road to Archeology. “[I collected] really anything I could get my hands on that had a history attached to them.” The stately, crumbling Roman temples! The grandeur of bygone Egypt! It was easy to fall in love with antiquity.

Yet, the 19th and 20th century stories of Black and non-White folk in Archeology and general fields of Discovery & Adventure have been largely unsung in our history books…

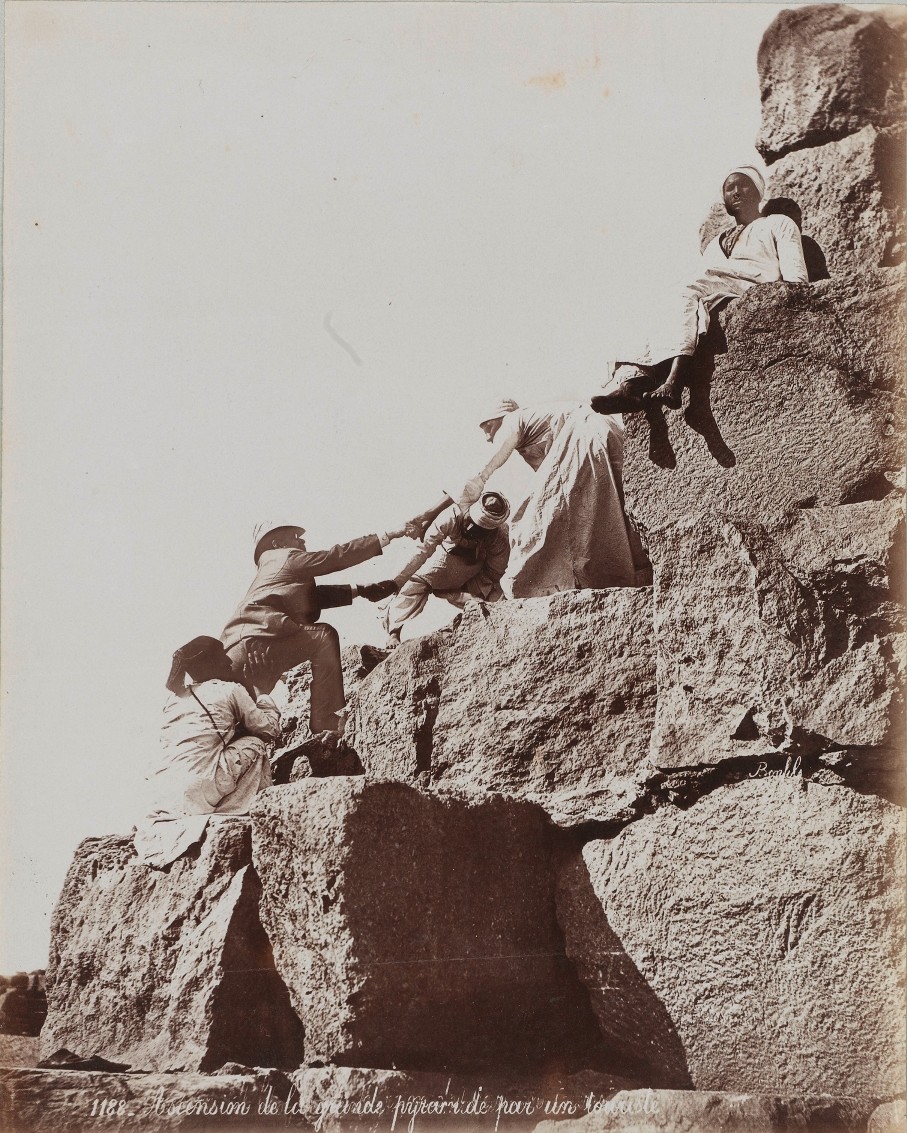

They are stories of dig assistants, and local guides – not unlike the first non-indigenous man to reach the North Pole. Yup, he was Black. They are also stories of complicated, internalised racism.

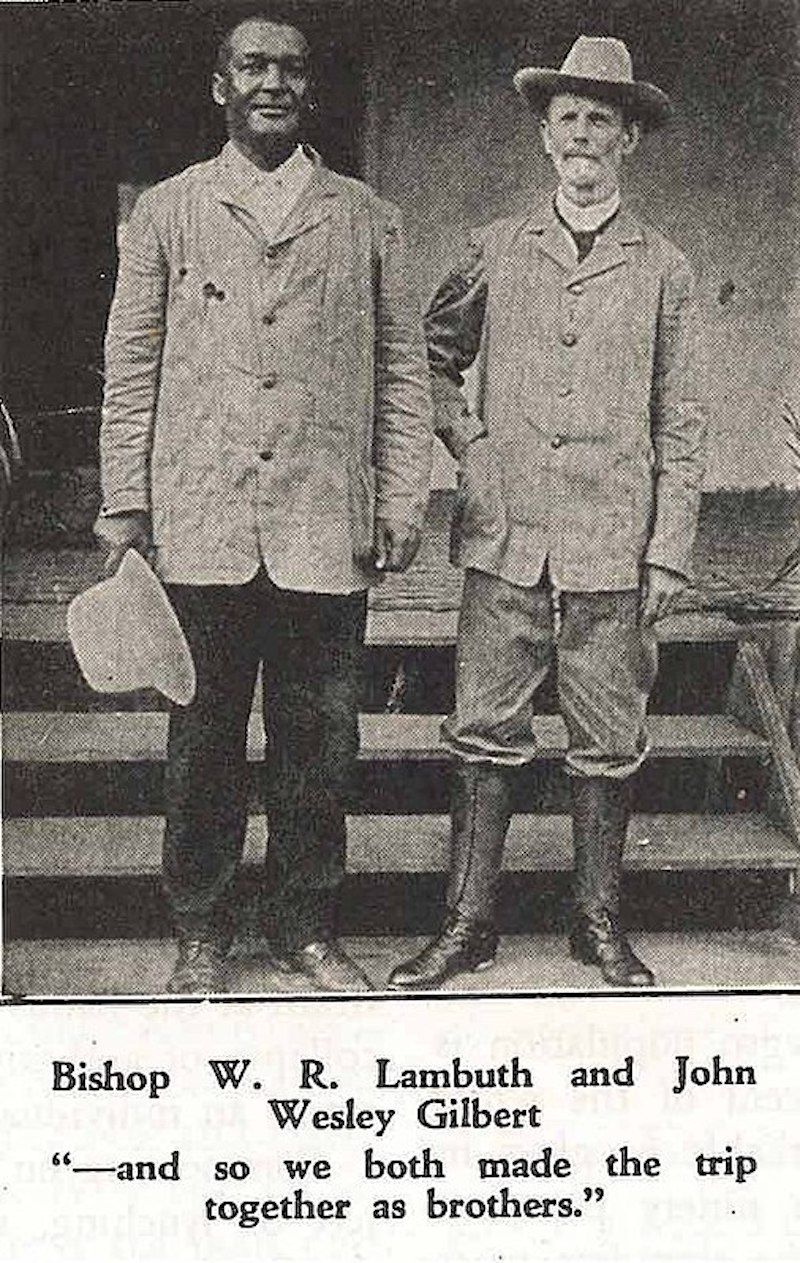

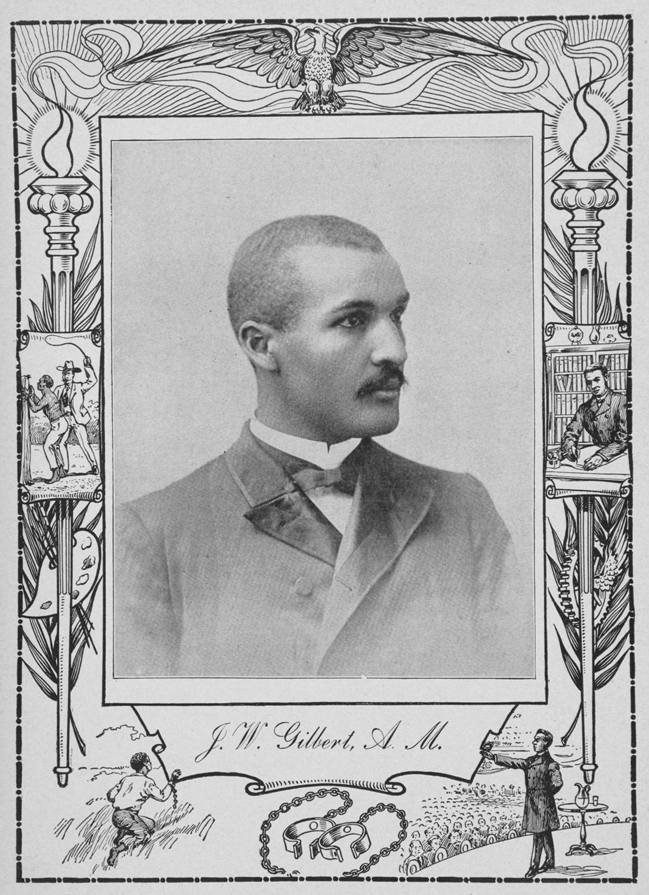

Consider John Wesley Gilbert, the first person to map out the ancient Greek city-state of Eretria in 1890. On the one hand, he was a groundbreaking Black Archeologist and Classicist; the first Black man to receive a masters degree from Brown University, and an African American pioneer in Greece.

Gilbert was an inspiration. But he was also a product of his time, which is a euphemism for saying that many Black American communities thought Gilbert’s internalised White supremacism eclipsed his Archeological achievements. “[Gilbert would] make the Afro-American…just as he was in the times of slavery,” reported the African American newspaper, The Appeal, in 1909, “perfectly willing to accept the White man as massa.”

“I had never heard of [Gilbert] until well after I finished my education,” says Franklin, who says we ought to “move the timeline closer to the year 2000 to start to see incremental changes in terms of the role of Black people in American archeology.”

The international “Society of Black Archaeologists” (SBA) was founded in 2012. The first Black American-led excavation in Egypt was in 2018 with Anthony Browder. “Today, there are over 80 Black archeologists but a number of them are still in graduate school,” says Franklin, “Going from 2 to over 80 is a big jump, but there are over 7,000 archeologists (including graduate students) who are members of the SAA (Society for American Archaeology) so this number is undoubtedly very conservative.”

If you are looking to fill your own brain and bookshelf with the words of Black and non-white Archeologists, Franklin has a treasure trove for you. “Anna Agbe-Davies, Whitney Battle-Baptiste, Nedra Lee, Ayana Flewellen, Jodi Skipper, Justin Dunnevant, Alicia Odewale, Alex Jones, Lewis Jones, and Cheryl Laroche. These individuals have done remarkable work in collaborating with Black descendant communities in their heritage projects.”

“Honoring their ancestors, challenging the control over their cultural patrimony, collaborating with Native Americans…I’ve learned a lot that has influenced my own research and writing,” she says, “Scholars like Sonya Atalay, Michael Wilcox, Tsim Schneider, Joe Watkins, and Dorothy Lippert have helped to decolonize our discipline.”

“Theresa Singleton’s work comes immediately to mind,” she adds, “She did her doctoral research on plantation slavery in Georgia and edited two books on African American archeology in 1985 and 1999.” Singleton’s work reminds us of how important it is to see Black archeologists excavate, study, and reclaim plantation spaces.

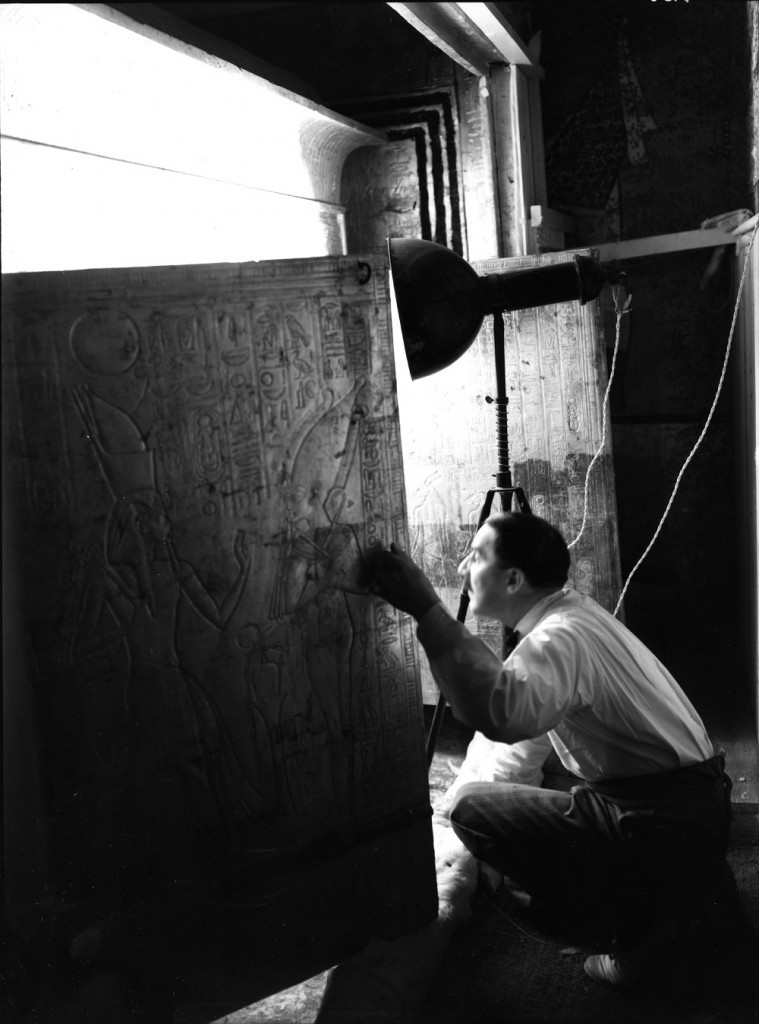

The same can be said of Egypt. In matters of Egyptology, Franklin doesn’t believe the Archeological community necessarily romanticises the era of King Tut’s discovery and Howard Carter’s work, simply because “Archeologists are unlikely to romanticise what we do!” It’s gruelling work. But as for the general public’s idea of Ancient Egypt? “Absolutely, yes.” Google “Cleopatra,” and you get Liz Taylor.

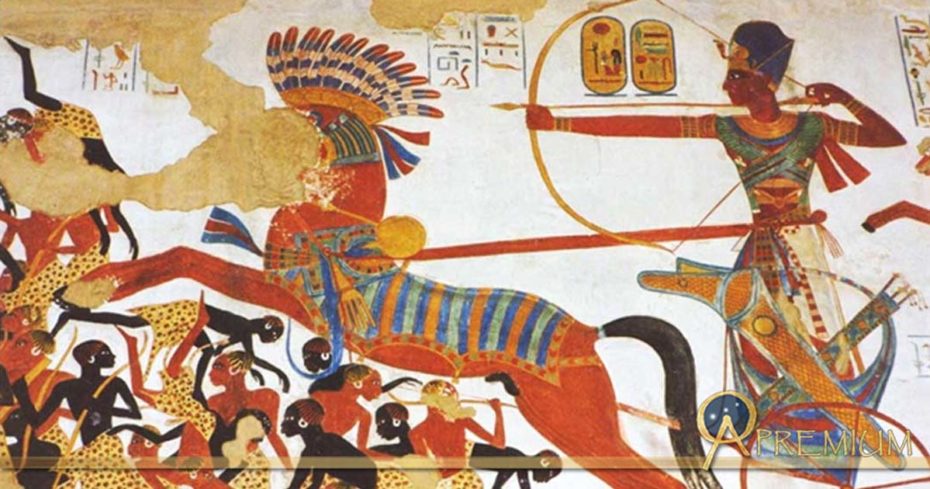

Egyptologists and scholars, have long argued the race of the ancient Egyptians. The question of their race was first raised in the 18th century as a product of the early racial concepts and was revived in mainstream debate by the Afrocentrist Movement in the 1970s. The Black Egyptian Hypothesis, stating that ancient Egypt was a predominantly Black civilization, is a theory which gained a large amount of traction and attention in the late 20th century. “Was Cleopatra Black?” asked Ebony magazine in 2012. While most scholars identify Cleopatra as essentially of Greek ancestry with some Persian and Syrian ancestry, a recent BBC documentary (Cleopatra: Portrait of a Killer) speculated that Cleopatra’s mother was African. Recent DNA tests conducted on the mummies of the ancient Egyptians link Pharaoh Rameses III and his son to Ugandan origin.

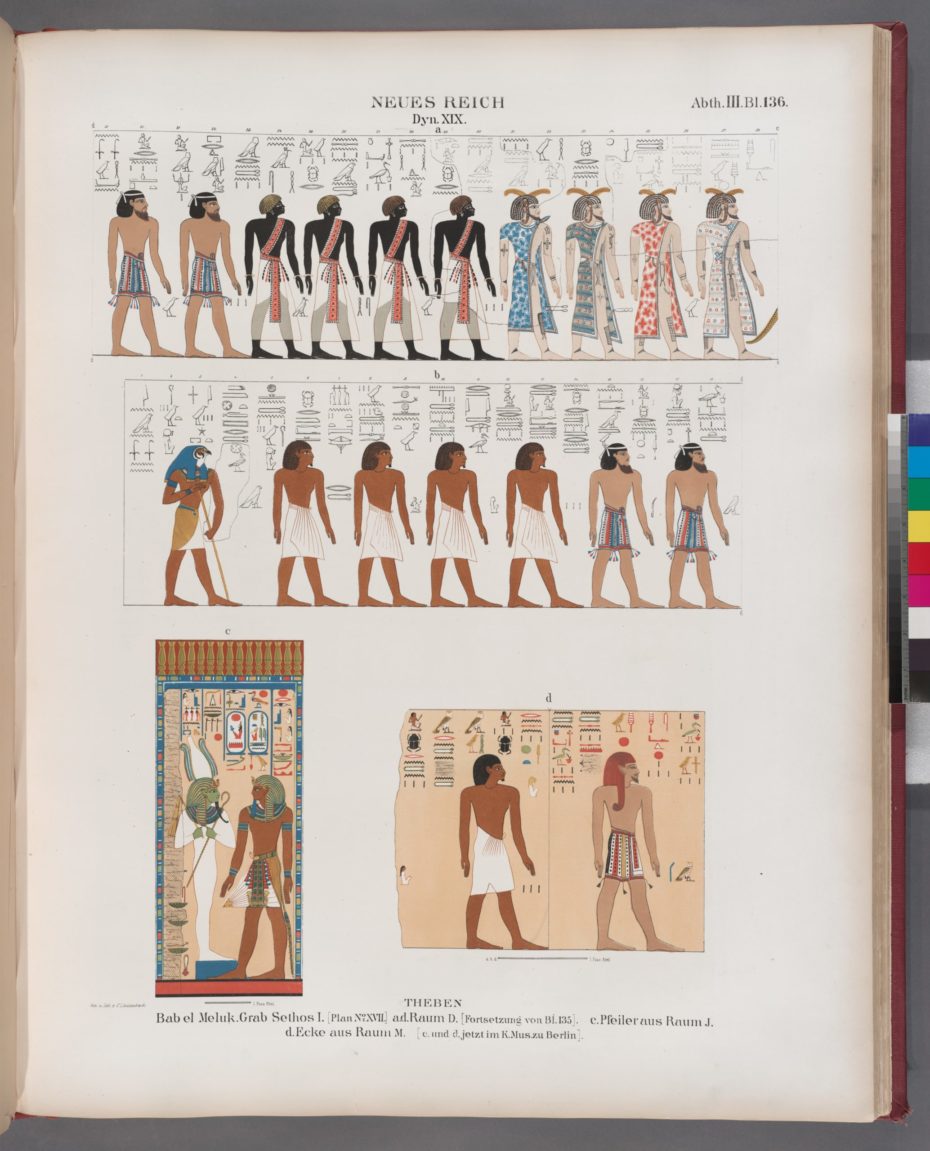

Diodorus, Aristotle, Herodotus and many ancient Greeks or Romans wrote that ancient Egyptians were a Black-skinned and “woolly haired people”. Diodorus himself indicated that ancient Egyptians were a colony of Ethiopians. “Kemet” is the ancient name for Egypt, which translates to ‘land of the black’, although mainstream scholars maintain that this is a reference to the fertile black soil which was washed down from Central Africa.

The Black Egyptian Hypothesis was met with profound disagreement pretty much right out of the gate when it was first publicly debated at a 1974 UNESCO symposium in Cairo. Ever since, the theory continues to be regarded widely as “junk history”, and most mainstream scholars believe quite simply that Ancient Egyptians looked like modern Egyptians.

But if we consider that tribes moved across the Sahara thousands of years ago from all over the African continent and settled on the banks of the Nile river and the Delta, it seems inevitable that people of darker complexions would have settled in Egypt. As indicated in art from the period depicting Egyptians and Nubians with the same skin colour, it’s far more likely that as a people, the Ancient Egyptians did not see themselves as a “racial” group and had something of “a love and hate relationship” with their Nubian neighbours, who they saw as “Others”, along with Libyans, ancient Berbers and so on.

While Afrocentrists and Eurocentrists have often used ancient history as a battle field for a race war, an interesting discussion thread found on Reddit takes an alternative stance on Black Egyptian Hypothesis:

“The problem arises when some people (some African Americans) take this truth that black people exist in Egypt and turn it into “all people in Egypt are/were black”. Anti blackness and a lack of proper African history teaching (such as the treatment of Egypt/North Africa as separate from ‘sub saharan Black Africa’) inevitably leads to some people wanting to proclaim historical narratives that may have truth in them but are not entirely true. But just as much as the ‘Black Egypt’ hypothesis is bad history and problematic […] those who would argue that Black people are/were non-existent in Egypt or North Africa are just, as if not more problematic.”

via Reddit

There’s a reason that the iconic, 1961 New York Times photograph of Louis Armstrong in Cairo, piercing the air with his trumpet, is still so electrifying. Does it have a damn thing to do with Archeology? Not really. Louis was a jazz man. But as he serenaded his wife to the backdrop of that Great Sphinx, his tangible, visual proximity to such an iconic place of non-white excellence hit a new, golden note – a declaration of love to Blackness across the African diaspora.

“Out of all of the research areas in Archeology, [the African diaspora] is where Black people have had some influence on the research questions, theoretical frameworks, and social justice agendas,” she concludes, “I hope to see this trend continue, since it has enriched our views of the past with a more diverse group of scholars contributing to shaping how we explore and construct the experiences of people of African descent. Yet, I also hope to see more Black archeologists pursuing research in Europe, on Native Americans, and so on. That is, if different experiences, backgrounds, and worldviews are good for knowledge production in general, then Black people shouldn’t be expected to only study our own past.”

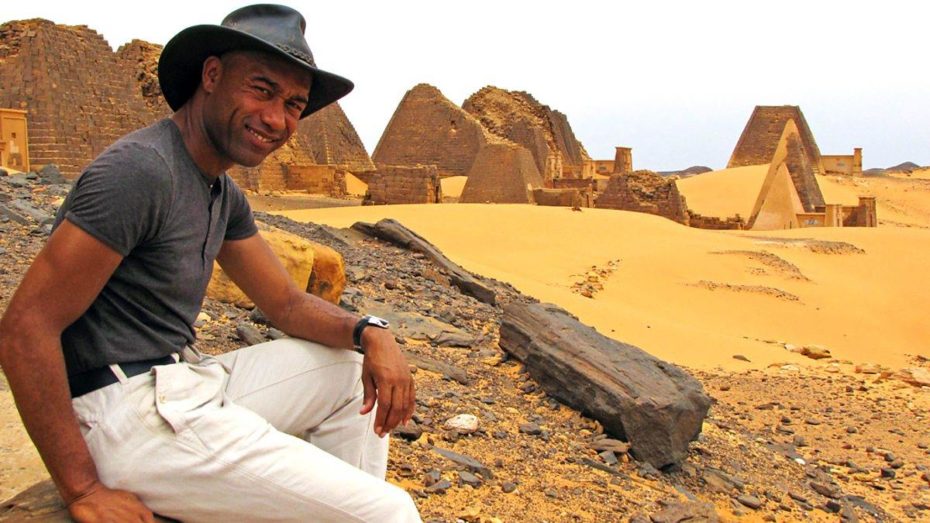

In the meantime, we’ll leave in the hands of a modern-day “Indiana Jones”, Dr. Gus Casely-Hayford, OBE; British curator and cultural historian, best known for his major BBC TV series The Lost Kingdoms of Africa, using new archeological and anthropological research to explore the pre-colonial history of some of Africa’s most important kingdoms…