Some people paint by numbers. Formality. Then there are those who paint with something else entirely. A kind of electric, lived experience. A place of intimacy with their subject matter that makes a portrait sing, and a still life tremble. Pan Yuliang was one of those people, albeit one who might’ve been left out of your history books. There was a time at the prestigious Pompidou art museum in Paris, when her artworks were stored in the archives under the category of “unknown artists”. She is also noticeably absent from 20th century Chinese Art history after 1949. But in the 1930s, this Chinese artist, a former sex worker, enticed the European art scene with her landscapes, still lifes, and nude portraits – illegal in China at the time – painted in the Western styles pioneered by the Impressionists, all while imbuing those works with her own unique eye and experiences. The result? A feminine tour de force who straddled the Western and Eastern art world as one of China’s first Modernist artists.

As we all know, getting an “in” with any bougie art scene has always been something more easily achieved by artists in middle to upper class social standings. Having a rich, benevolent relative to foot a Fine Arts school bill doesn’t hurt either, but Pan (née Xiuquing) wasn’t born into those resources…

Orphaned as a child and sold into prostitution by her uncle at 14-years-old, she spent a pivotal part of her youth calling a brothel in Wuhu her home. It was there that she not only made a name for herself amongst clientele, but met an important customs official, Pan Zanhua, who bought her freedom. She even became his second wife; a concubine; and in 1917 they moved to the bustling cultural epicentre of Shanghai – one of the first ports to open to international trade in the 19th century, like a concentrated portal to the rest of the world.

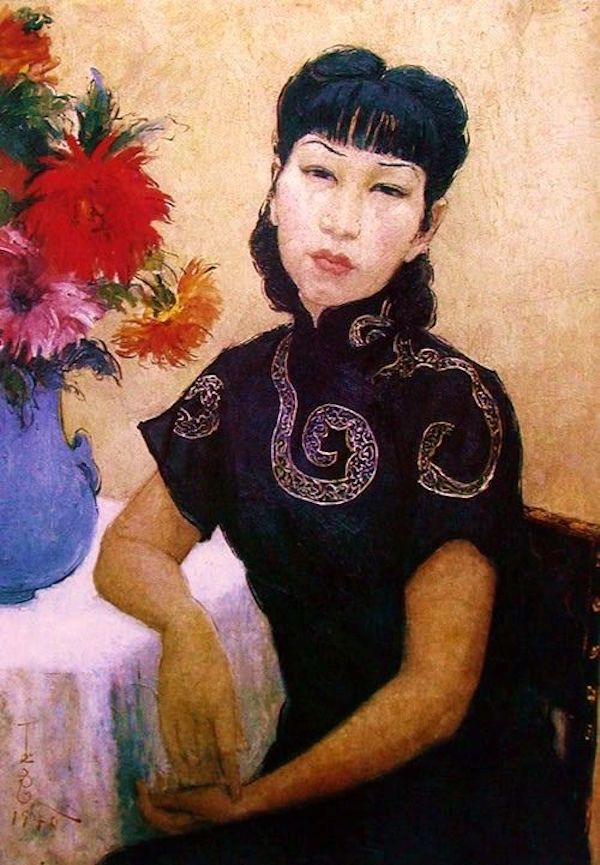

In Shanghai, she took her husband’s name (becoming Pan Yuliang), and learned to read and write. She also started to paint, initially through lessons from a neighbour and then at the Shanghai Art Academy, a rather radical school for many reasons. For one, it encouraged students to play with Western painting styles. It also decided to accept its first-ever batch of women students, of which Pan would become a standout.

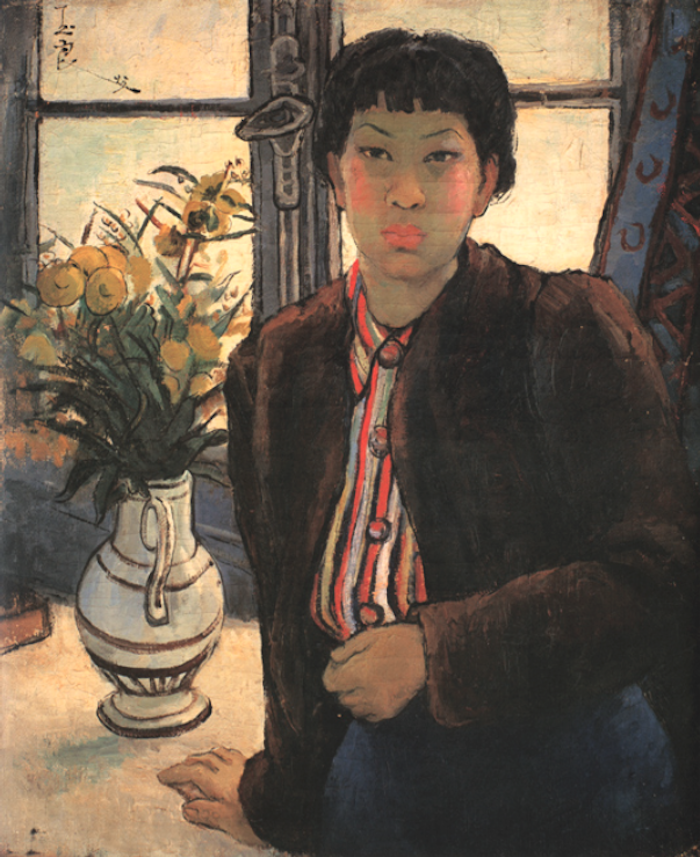

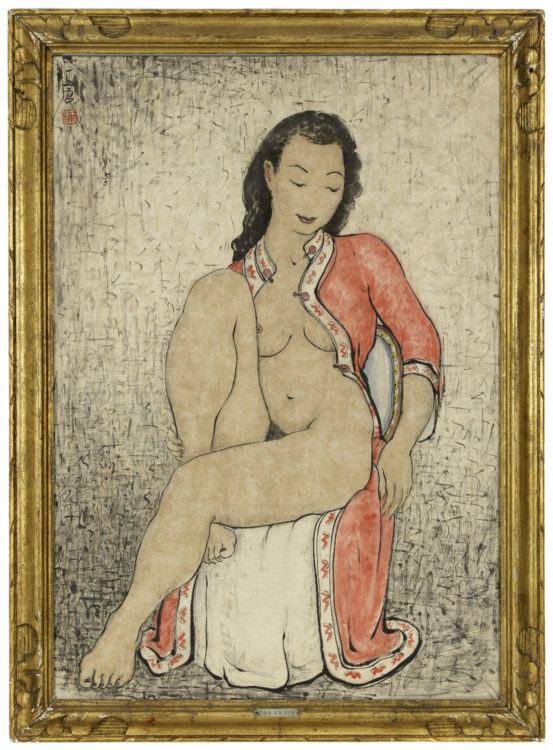

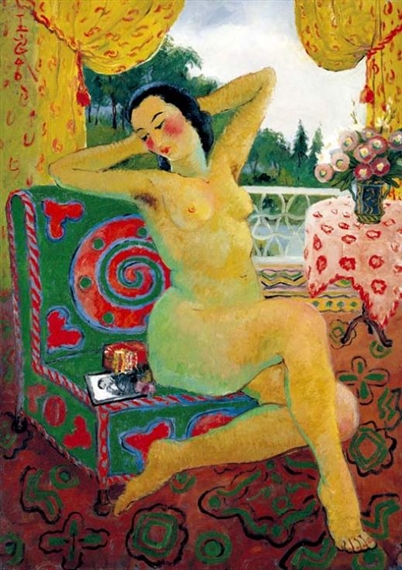

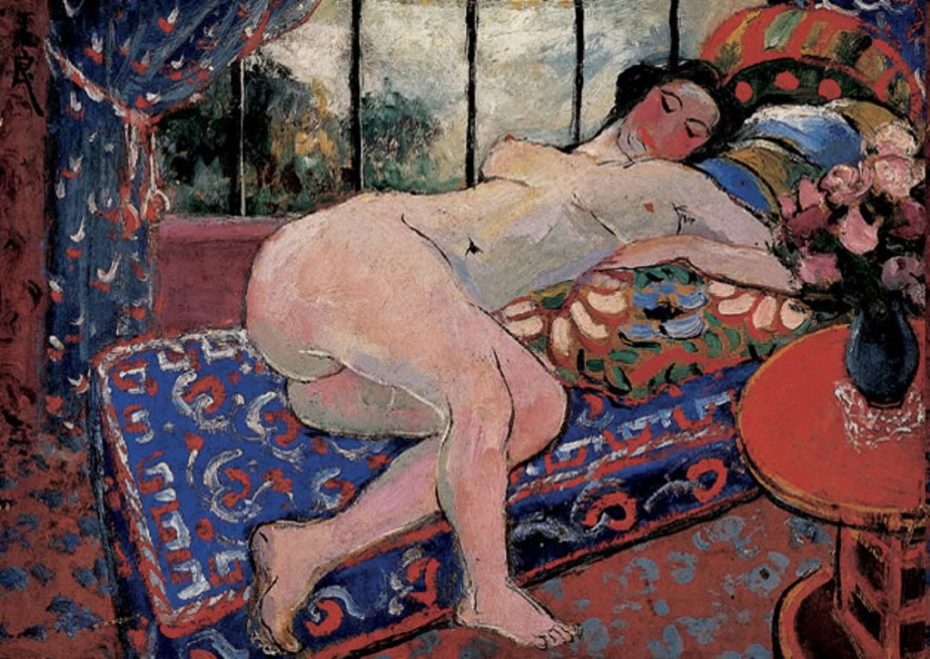

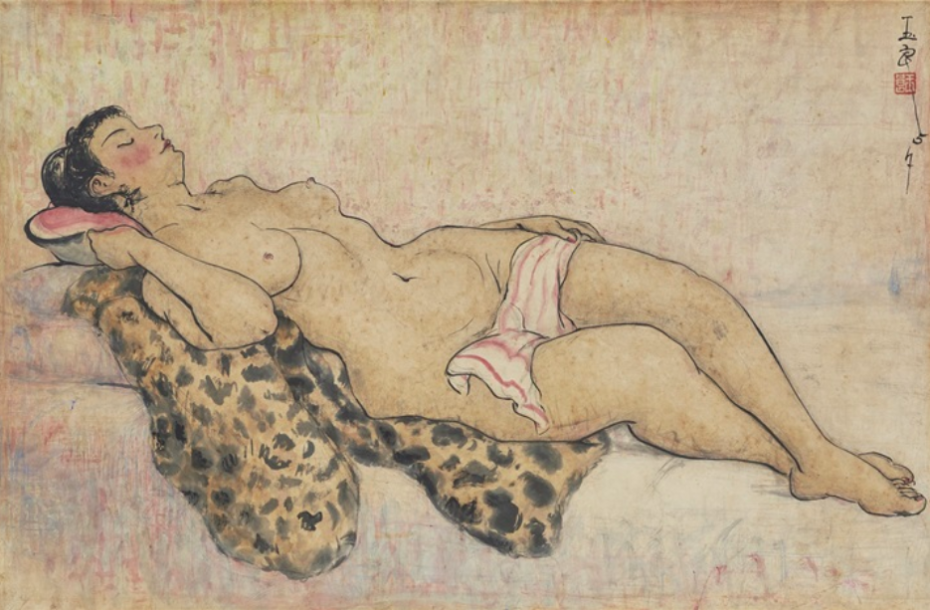

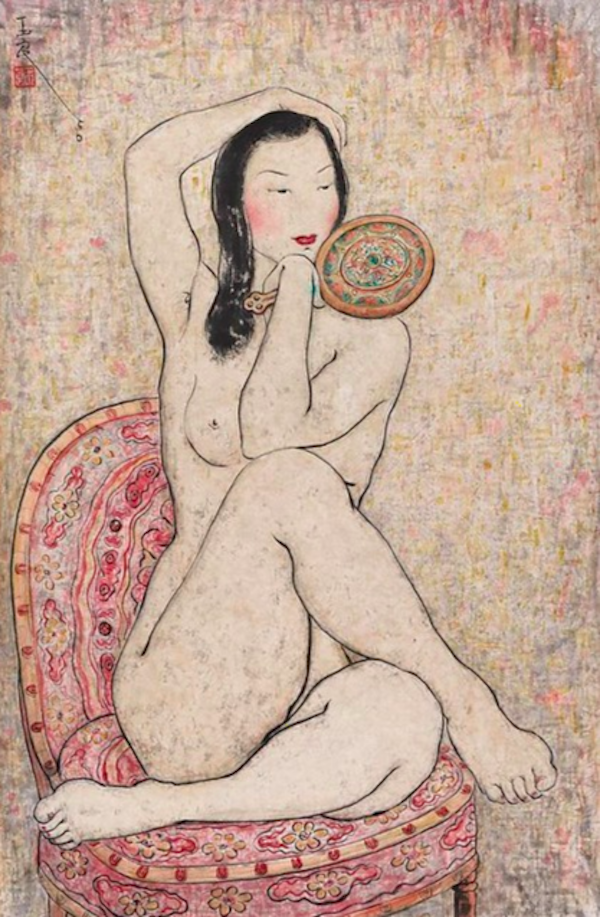

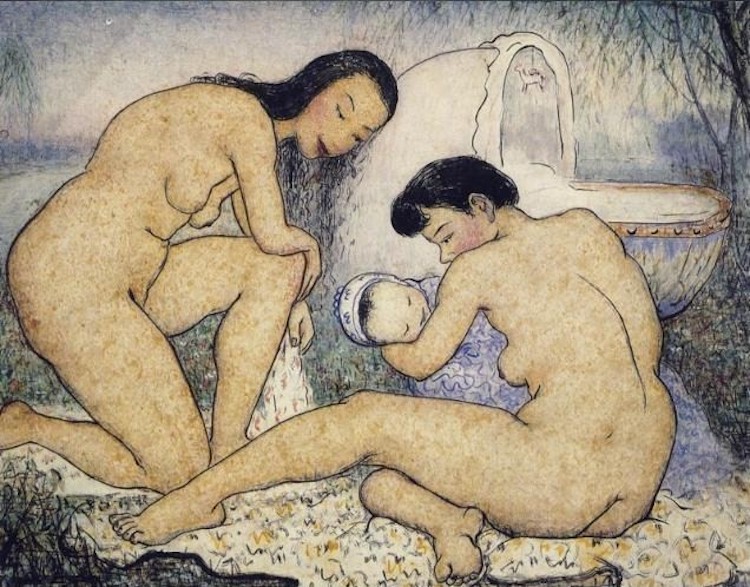

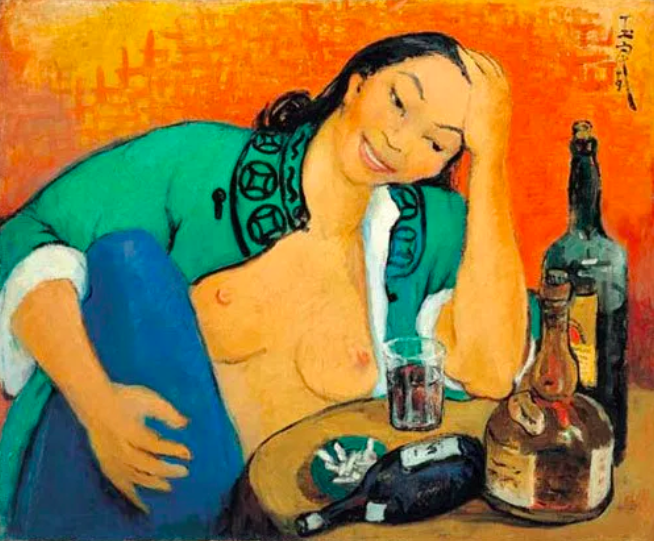

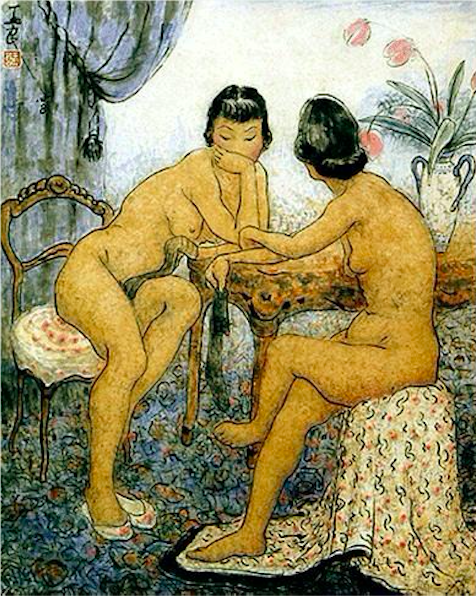

It was one thing to paint tantalising still lifes of fruit and veg by a shiny vase like Cézanne. It was another entirely to paint nude models – and, to paint nude models as a woman painter. Pan was exceptionally good at both, soliciting faculty praise and societal uproar at her scantily clad “Westernised” ladies.

Critics declared the moral and cultural bankruptcy of Pan’s headmaster, Liu

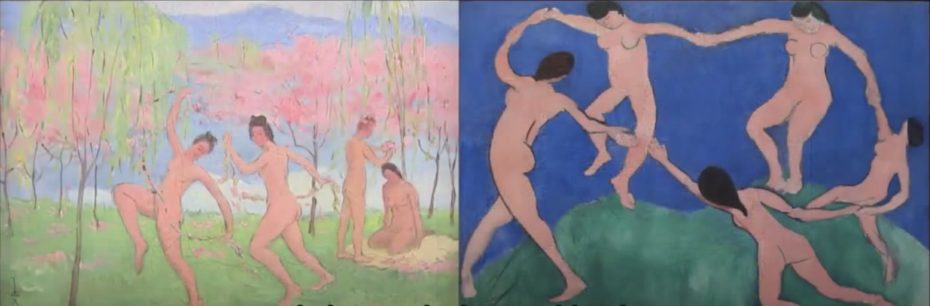

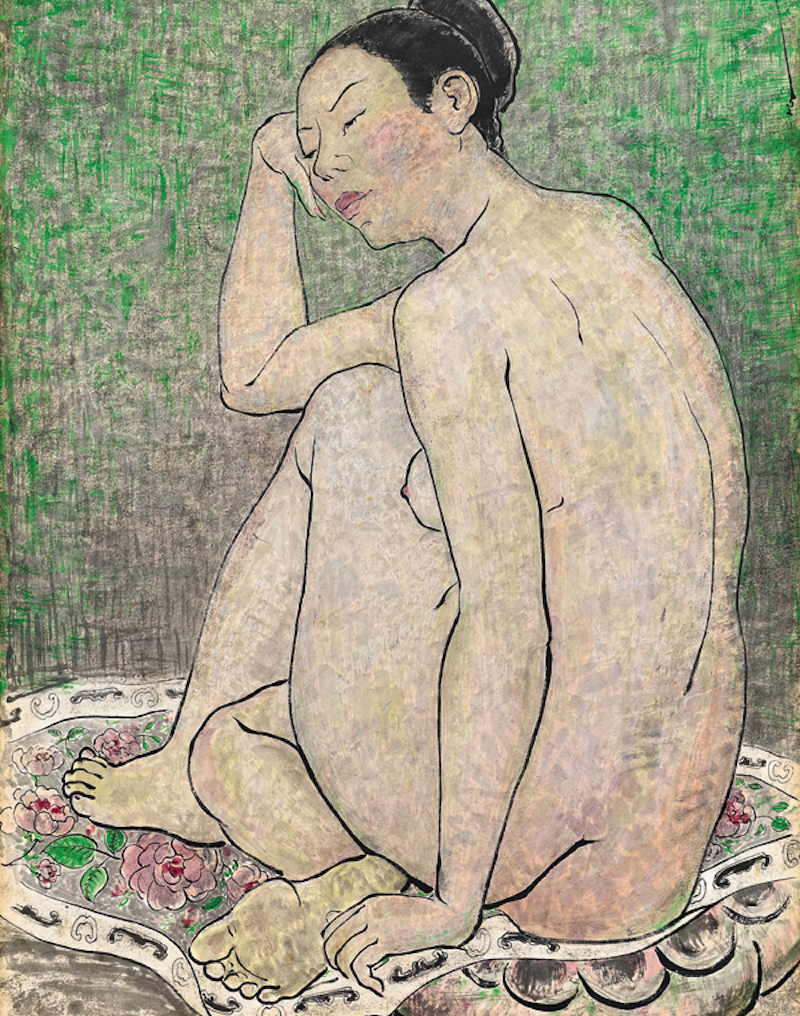

Haisu, calling him a perverter of “truth and humanity.” But Pan stuck to her gut and continued to illustrate the power, grace, and sisterhood of these bare naked ladies in a style that blended traditional Chinese ink work with the brushstrokes of Western European artists.

Her paintings were sensual but never singularly confined erotic scenes. Perhaps there was something about Pan’s own personal proximity to nakedness – literally and figuratively, in all of its vulnerability and power. She didn’t just paint women for galleries. She painted women for herself. She painted women for women.

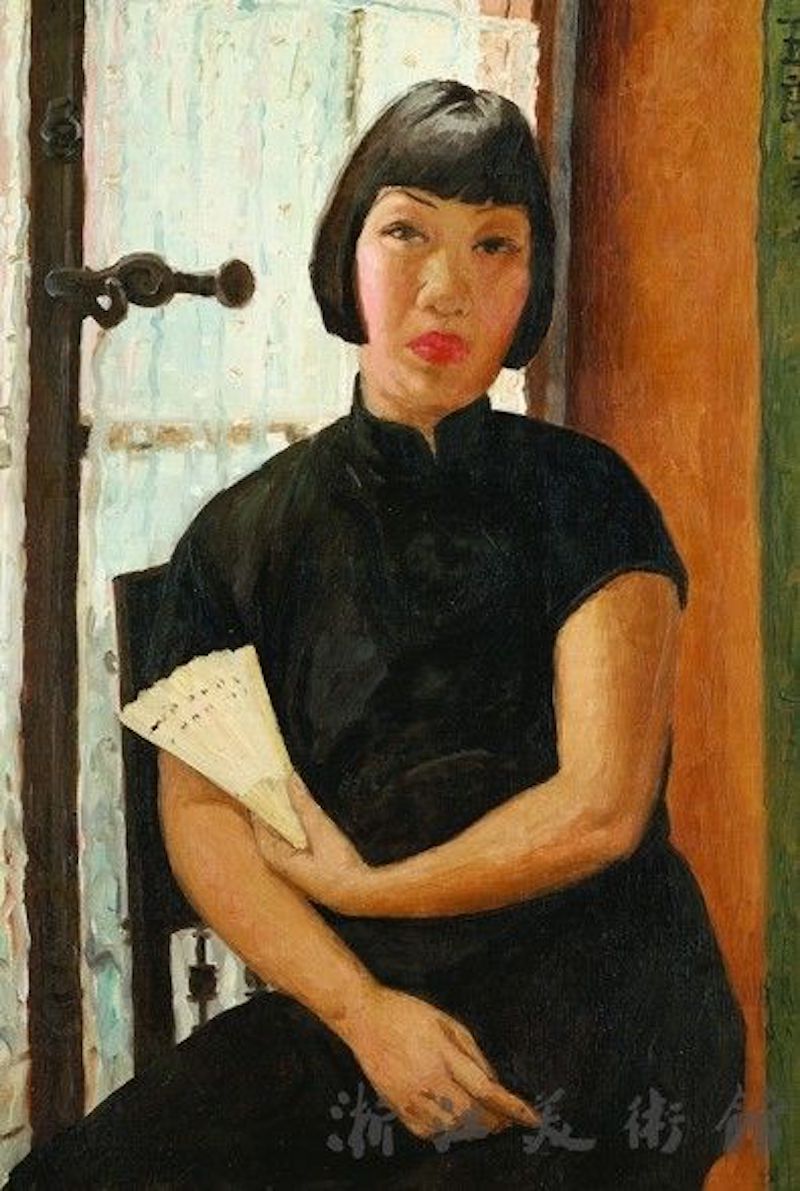

Pan’s more traditional works, featuring Chinese landscapes and themes, still showed a poetic confluence of the worlds in their dappled, Impressionistic style. And even when Pan’s women were dressed, they were prolific, walking a beautiful line between Eastern and Western sartorial flair.

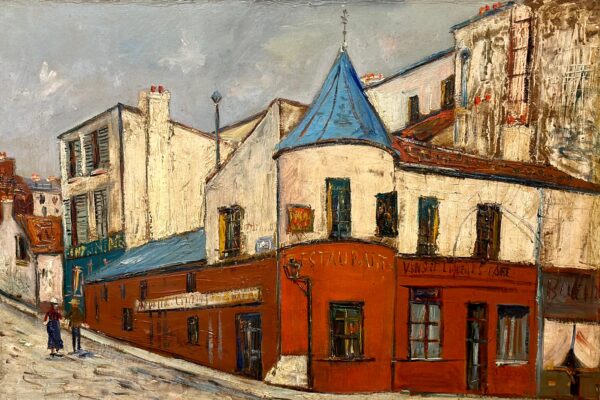

With her talent irrefutable and the art world’s eyebrows well raised, Pan became the first ever woman in China to win a scholarship to study in Europe. In 1922 she set off for Paris, where she took plein-air day trips to paint, found a foot in the door amongst the closed circles of the Beaux Arts rising stars, and returned to Shanghai as a woman of an even more global perspective.

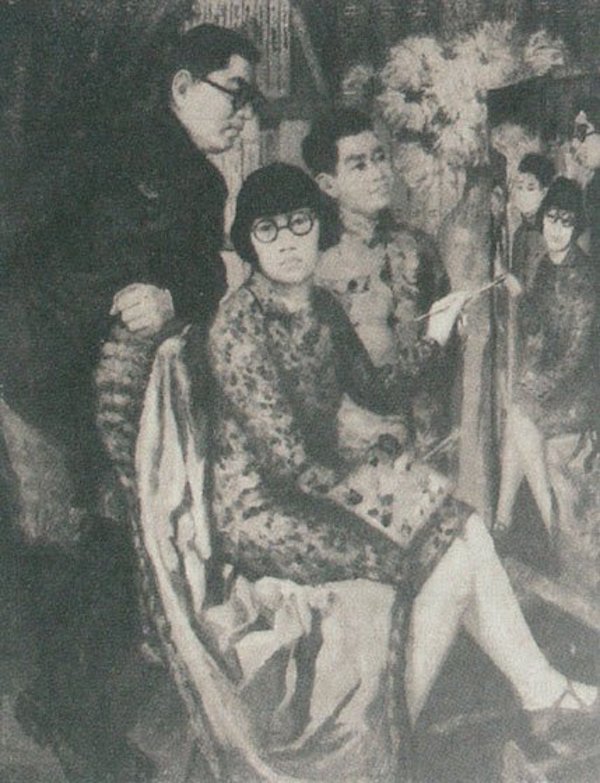

But success was a double edged sword. Embracing Western styles made both her a figure of intrigue and ostracisation back in China, where folks also stigmatised her due to her work in prostitution. The hostility towards her – not just her work – was so extreme that she moved back to Paris in 1937, where she soaked up the Jazz Age and became a teacher at the Beaux-Arts School, albeit on a salary half that of her male colleagues. She also co-founded the Chinese Artists Association of Paris, which formed a close community of ex-pats; many belonging to the first wave of Chinese artists in France.

The popularity of Pan’s nude ladies in Europe took her on tour to Germany, Greece, Italy, the United Kingdom, and beyond. But under the gaze and fleeting interest of European art critics, something shifted in her work. Pan entered a period in which she began repeatedly painting herself…

Perhaps it was the neglect she felt as an outsider in the Paris art world. Perhaps it was the homesickness; a longing to return to China and find acceptance. At the time, critics showed little interest in her self-portraits.

By 1950, most of her ex-pat peers from the first wave of Chinese artists had returned to Maoist China, some becoming high level members of the Chinese Communist Party, while Pan stayed behind in Paris. In 1956, amidst diminished diplomatic relations between France and China, Pan received a letter from her husband informing her that the French government would not let her return to China with her artworks – all of which were considered French property. She was advised to delay her return once relations improved, but Pan never did return to China.

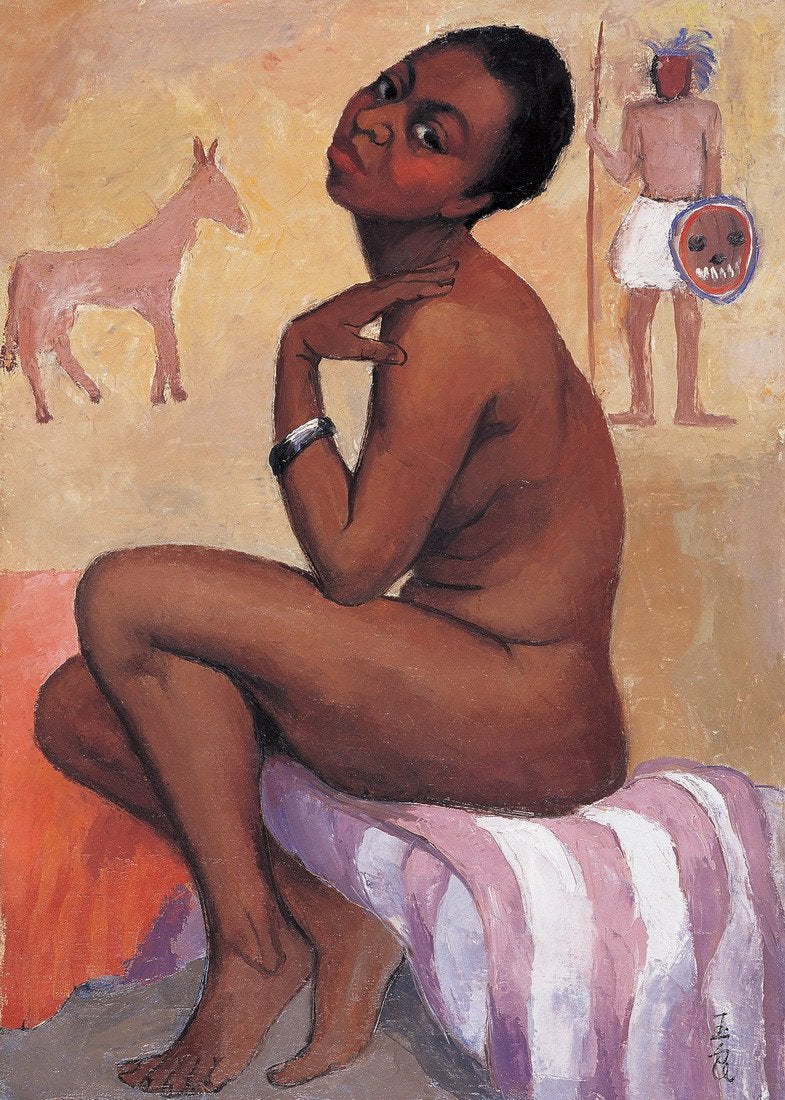

She became isolated in the years before her death. Her work appears to become more explorative of subjects considered as the “Other” in her adopted Western world.

Pan Yuliang died in 1977 in an attic in suburban Paris, leaving some four thousand artworks behind. She is buried at the Montparnasse cemetery.

It was her last wish to take all the artworks back to China, where in 1984, mystified researchers began cataloguing the prolific but unfamiliar archives of an artist who had been all but been erased from the nation’s history of art. Unsure of what to make of this “misfit” artist in China’s nationalist narrative, it wasn’t until several years later that her forgotten legacy was reintroduced to collectors of the modern world.

Today, most of her art remains at a provincial museum in China, the same one where her estate was first sent in the mid 1980s.

“I encountered her ‘ghost’ at the museum,” recalls Mia Yu, an art historian who created a short film about her personal journey ‘searching’ for Pan. “It was a defining moment. In 2017 […] myself and a few other artists went to Anhui Provincial Museum where her four thousand works and archives are currently being held. The museum is housed in an old Soviet-styled building located in an area of the city that is equally grey and uncharacteristic. Although the museum was closed for renovation, the collection manager allowed us to see the works in the storage […] We sat around the polyfoam board and waited and waited. It was very cold. As time passed, I felt we were participating in a collective ritual of calling back Pan Yuliang’s spirit.”

The scattered legacy of one of China’s first modern woman artists is laid out in this moving video made by Mia Yu for a 2017 exhibit in Berlin:

As for clues of Pan in Paris, you can see some of her works at the Cernuschi Museum. It’s a little musée tucked inside a hôtel particulier by Park Monceau – so we suggest packing a picnic with your trusty Paris guidebook, and making a day out of your visit.

There was both a 2004 Chinese television series on her life entitled “Hua Hun: Pan Yuliang” and a full length movie, A Soul Haunted by Painting (1994). The latter is available for free on YouTube through a series of videos: